Karl Marx &

Communication @ 200:

Towards a Marxian Theory of Communication

Christian Fuchs

University of Westminster, London, UK, christian.fuchs@triple-c.at, @fuchschristian, http://fuchs.uti.at

Abstract: This contribution takes Marx’s bicentenary as occasion for reflecting on foundations of a Marxian theory of communication. It aims to show that Marx provides a consistent account as foundation for a critical, dialectical theory of communication. The article first discusses the relationship of communication and materialism in order to ground a communicative materialism that avoids the dualist assumption that communication is a superstructure erected on a material base. Second, the paper provides an overview of how Marx’s approach helps us to understand the role of the means of communication and communicative labour in capitalism. Third, it conceives of ideology as a form of fetishised communication and fetishism as ideological communication. Given that communicative capitalism is a significant dimension of contemporary society, it is about time to develop a Marxian theory of communication.

Keywords: Karl Marx, bicentenary, 200th birthday, anniversary, communication, critical theory of communication, critical political economy, Marxist theory, capitalism

1. Introduction

May 5, 2018, marks Karl Marx’s bicentenary. He was born on May 5, 1818. 100 years later, the German socialist and historian Franz Mehring, author of one of the first biographies of Karl Marx (Mehring 2003/1936), wrote on occasion of Marx’s centenary: “Karl Marx’s centenary directs our view from a gruesome presence to a brighter future just like a bright sunbeam that breaks through dark and apparently impenetrable cloud layers […] Tireless and restless critique […] was his true weapon. […] To continue working based on the indestructible foundations that he laid is the most worthy homage we can offer to him on his one hundredth birthday” (Mehring 1918, 11, 15).

Given the gruesome presence we live in today that features the expansion and intensification of nationalisms and neo-fascisms, the threat of a new World War, environmental, economic and political crises, Mehring’s words are as true on the occasion of Marx’s bicentennial as they were 100 years ago.

Marx was first and foremost a critic and critical theorist, which entailed that he was a critical economist, critical philosopher, critical political scientist, critical sociologist, critical journalist, and revolutionary activist. The task of this contribution on the occasion of Marx’s bicentenary is to show that he was also a critical communication scholar. This circumstance has often been forgotten in radical theory because communication is often ignored or dismissed as being an unimportant superstructure.

The article shows in three steps how Marx’s works can ground a critical theory of communication: Section 2 introduces aspects of communicative materialism. Section 3 discusses means of communication and communicative labour. Section 4’s focus is on foundations of ideology critique. Section 5 draws conclusions.

2. Communication’s Materiality: Dialectical, Critical, Communicative Materialism

In the Theories of Surplus-Value, Marx speaks of the existence of “non-material production” (Marx 1867-63, 143) that entails the production of books and paintings, artistic creation, writers, engineers, the work of “executant artists, orators, actors, teachers, doctors, clerics, etc.” (Ibid., 144). In a newspaper article, he speaks of privileges as “immaterial goods” (Marx 1848, 477). In the Grundrisse, Marx argues that value is “something immaterial, something indifferent to its material consistency” (Marx 1857/58, 309).

According to these assumptions, information and its production are not part of the “material base”, but of the “superstructure”. Such a dichotomy between materiality and immateriality can indeed be found in particular versions of Marxist thought. So for example the Small Dictionary of Marxism-Leninism defines the superstructure as “ideas (political, legal, cultural, scientific, ideological, moral, artistic ones)” (Buhr and Kosing 1979, 46). It understands the superstructure as the “ideological societal relations of a societal formation” (Ibid.) and consistently speaks of “institutional and ideal contents” (Ibid., 47). The problem is that the question about matter is one about the world’s substance and ground. If one assumes that there is something immaterial in the world, then there must be two substances – matter and spirit. The implication then is not just religious and esoteric, namely that spirit exits as a substance in the universe, but the human mind is also seen as independent from matter.

Marx does, however, not frequently use the concept of immateriality. He mainly employs it in drafts. In Capital, he in contrast says that “the ideal is nothing but the material world” translated in “the mind of man” and into “forms of thought” (Marx 1867, 102). He also writes about “the intellectual potentialities [geistige Potenzen] of the material process of production” (Ibid., 482). In the German Ideology, Marx says that the “production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men – the language of real life” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 36). The mind “is from the outset afflicted with the curse of the being ‘burdened’ with matter” (Ibid., 43-44).

Taken together, these formulations imply that information and communication are forms of matter and that the production of information is part of the material production process. When Marx speaks of the “material intercourse of men”, then he not just describes the human thought process, but how humans in the communication process co-relate their thoughts and thereby produce a new whole. By stressing that communication is “the language of real life”, Marx foregrounds that information and communication are not unreal or immaterial, but part of humans’ production and reproduction processes in everyday life.

But just like communicative idealism that sees communication as a superstructure, also a vulgar communicative materialism should be avoided. Stalin’s writings on linguistics are an ideal-type of vulgar communicative materialism: Language “radically differs from the superstructure. Language is not a product of one or another base, old or new, within the given society, but of the whole course of the history of the society and of the history of the bases for many centuries” (Stalin 1972, 5). Language is “common to all members of that society, as the common language of the whole people. Hence the functional role of language, as a means of intercourse between people, consists not in serving one class to the detriment of other classes, but in equally serving the entire society, all the classes of society” (Stalin 1972, 5-6). “Language, on the contrary, is connected with man's productive activity directly, and not only with man's productive activity, but with all his other activity in all his spheres of work, from production to the base, and from the base to the superstructure. […] For this reason the sphere of action of language, which embraces all fields of man's activity, is far broader and more comprehensive than the sphere of action of the superstructure” (Ibid., 9). “Language, as a means of intercourse, always was and remains the single language of a society, common to all its members” (Ibid., 20).

Stalin’s writings on language fulfilled an ideological purpose: He wanted to stress that language is the constituting feature of the nation. In Marxism and the National Question, Stalin (1913, 306) stresses for example that “a common language is one of the characteristic features of a nation”. Instead of seeing its ideological and dominative character, Stalin reified the nation.

The humanist Marxist Leo Kofler (1970) criticised Stalin’s approach to language as reductionist and mechanistic:

“Stalin primarily notices language’s emblematical technical, phonetic-morphological side, i.e. its relatively fixed side. However, his dialectically untrained eye is not capable of seeing what has inadequately been called the ‘stylistics’, but can better be termed language’s ‘life’ as the fully valid and and true essence of language. His writing completely neglects this side of language. But this ‘life’ constitutes the ideological and therefore changing moment of language, or, better expressed, the ideological and therefore necessarily changeable moment of language. Technology and life of language are related to each other like form and content” (Ibid., 135-136)

Kofler’s point is that Stalin only focuses on the syntax and technology of language and leaves out its use, contents, semantics, and pragmatics. A dialectical approach to language needs to take into account its formal and semantic side, aspects of technology and culture, the economic and non-economic, etc.

A small number of

approaches that are today widely ignored, forgotten or undiscovered have within

Marxist theory stressed the material character of communication. Raymond

Williams points out that many Marxist approaches separate the economy and

culture and are not “materialist enough” (Williams 1977, 92, 97). It is idealist to separate

“’culture’ from material social life’ (Ibid., 19).

In such idealist approaches, “intellectual and cultural production […] appear

to be ‘immaterial’” (Williams 1989, 205). Williams

criticises approaches that separate matter and ideas either temporally by arguing

that first comes “material production, then consciousness, then politics and

culture” or spatially by assuming that there are levels and layers built on the

economic base (Williams 1977, 78). Language and

communication are material practices of production (Ibid.,

165). Williams speaks of “the material character of the production of a

cultural order” (Ibid., 93; for a detailed

discussion of how the communication concept is related to William’s cultural

materialism, see Fuchs 2017b).

Georg Lukács (1986a; 1986b) argues with his concept of teleological positing that goal-oriented production is the key feature of humans and society. Language and communication are for Lukács key features of society, a complex that enables the social reproduction of society (for a detailed discussion, see Fuchs 2016a, Chapter 2). Ferruccio Rossi-Land (1983) stressed the work-character of communication (see Fuchs 2016a, Chapter 6). Horst Holzer (1975, 30) stresses that “humans produce communicatively and communicate productively” (see Fuchs 2017a).

Such approaches foreground the material character of communication, which means that communication is the material production and reproduction process of social relations, social systems, organisations, groups, institutions, subsystems, society, and sociality. Communication is at the same time identical and non-identical with the economy and the work process: Just like all production, communication is purposeful: It aims at creating social relations. But communication also has a differentia specifica that makes it different from other work processes: It creates and spreads meanings and therefore is a meaning-making production and work process.

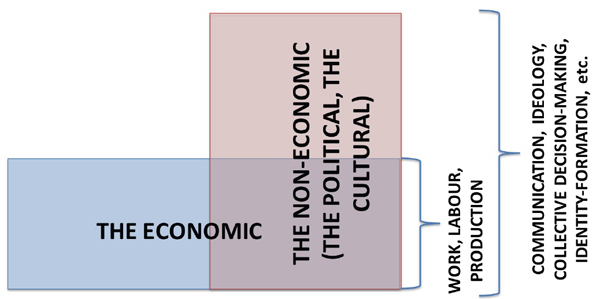

Figure 1 shows the relationship of the economic and the non-economic. Communication is a process that spans across both realms.

Figure 1: The relation of the economic and the non-economic in society

That communication is a particular type of production is

one of its important features. But it is not just production, but social

production. We do not produce and communicate alone and in isolation, like

Robinson Crusoe on his island, but in company, in common, and in processes of

co-operation. Marx stresses the social character of communication:

“Language is as old as consciousness, language is practical, real consciousness that exists for other men as well, and only therefore does it also exist for me; language, like consciousness, only arises from the need, the necessity, of intercourse with other men. Where there exists a relationship, it exists for me: the animal does not ‘relate’ itself to anything, it does not ‘relate’ itself at all. For the animal its relation to others does not exist as a relation. Consciousness is, therefore, from the very beginning a social product, and remains so as long as men exist at all” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 44).

That communication and language are social also means that humans develop, create and communicate names for instances of being because “they use these things in practice, […] these things are useful to them” (Marx 1881, 539). “At a certain stage of evolution after their needs, and the activities by which they are satisfied, have, in the meanwhile, increased and further developed, they will linguistically christen entire classes of these things which they distinguished by experience from the rest of the outside world. […] Thus: human beings actually started by appropriating certain things of the outside world as means of satisfying their own needs, etc. etc.; later they reached a point where they also denoted them linguistically as what they are for them in their practical experience, namely as means of satisfying their needs, as things which ‘satisfy’ them” (Ibid.).

One of Marx’s main critical sociological insights is that in capitalism and society in general, everything existing in and in constituted through social relations: The commodity, capital, capitalism, labour, money, value, classes, exploitation, domination, social struggles, communism, etc. are social relations. Marx in this context compares humans to the commodity:

“In a certain sense, a man is in the same situation as a commodity. As he neither enters into the world in possession of a mirror, nor as a Fichtean philosopher who can say 'I am I', a man first sees and recognizes himself in another man. Peter only relates to himself as a man through his relation to another man, Paul, in whom he recognizes his likeness. With this, however, Paul also becomes from head to toe, in his physical form as Paul, the form of appearance of the species man or Peter” (Marx 1867, 144, Footnote 19).

Marx here stresses that the human species and the human being are constituted through social relations. By making a metaphorical comparison to the commodity, he neither means that all social relations are instrumental and aimed at profit nor that social relations are a form of exchange. He rather stresses that the commodity as social relation reveals something about capitalism and society in general. In commodity exchange, buyer and seller relate to each other and exchange products (such as money and certain goods) as equals that were created under specific social conditions. A quantitative relationship of exchange is established. At the same time, any commodity exchange just like any other social relation has general features of human sociality such as the use of means, content, meanings, context, and impacts of communication.

Social relations need to be produced and reproduced. Communication is the production and reproduction process of social relations and therefore of society. Marx stresses that language and communication are social relations and that they constitute social relations. Society is possible because it is based on the social character of language and communication and the communicative character of social relations.

“Not only is the material of my activity given to me as a social product (as is even the language in which the thinker is active): my own existence is social activity, and therefore that which I make of myself, I make of myself for society and with the consciousness of myself as a social being” (Marx 1844c, 298).

“Production by an isolated individual outside society – a rare exception which may well occur when a civilized person in whom the social forces are already dynamically present is cast by accident into the wilderness – is as much of an absurdity as is the development of language without individuals living together and talking to each other” (Marx 1857/58, 84).

“As regards the individual, it is clear e.g. that he relates even to language itself as his own only as the natural member of a human community. Language as the product of an individual is an impossibility. But the same holds for property. Language itself is the product of a community, just as it is in another respect itself the presence [Dasein] of the community, a presence which goes without saying” (Ibid., 490).

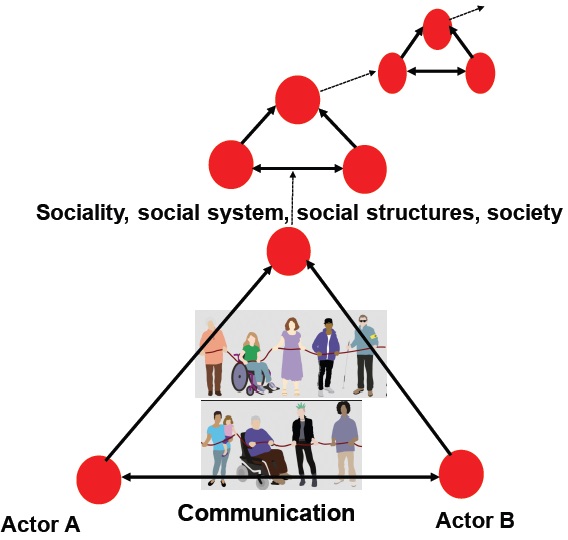

Figure 2: Model of communication as social production process

Figure 2 shows a model of communication as social production process: Humans through communication produce the social that enters into new communication processes so that sociality is an open totality. Humans produce and reproduce the social (including social relations, social structures, social systems, groups, organisations, institutions, subsystems, society) and the (re-)produced social structures again and again enter new communication processes that in a self-reflexive manner create and re-create social structures. Expressed differently, one can say that society is a realm constantly emerging out of the dialectic of structures and human agency, in which communication is the productive process of mediation, in which humans co-produce social structures that enable and constrain human action so that the dialectic constantly dynamically reproduces itself, human sociality, social structures and society. Communication is the productive mediating process that organises the dialectic of structure and agency as open totality.

Marx not only analysed the communication process, but also the role of the means of communication and cultural/communicative labour in capitalism.

3. The Means of Communication and Communicative Labour in Capitalism

In Capital Volume 1’s technology-chapter “Machinery and Large-Scale Industry”, Marx (1867) advances a dialectical concept of technology. He stresses that capitalist technology has a contradictory character: It advances new potentials for co-operation and welfare for all, but is under capitalist conditions also a means of exploitation and domination. Capitalist technology is ambivalent, ambiguous and contradictory (for a detailed discussion, see Fuchs 2016b, Chapter 15). Marx’s dialectical approach to technology and society allows us today, in the age of social media, big data, the Internet of things, cloud computing, mobile communication, industry 4.0, artificial intelligence, etc., to avoid techno-optimism that celebrates every innovation and is uncritical about negative impacts as well as techno-pessimism that fights technology as such and wants to return to a society without modern technology that is shaped by toil. The point of progressive technology and communications politics is to appropriate, transform, re-design, re-shape the means of production and the means of communication as particular means of production into a progressive direction, which requires societal change along with technological transformation.

So Marx on the one hand stresses the dominative role of capitalist technology: “Every development of new productive forces is at the same time a weapon against the workers. All improvements in the means of communication, for example, facilitate the competition of workers in different localities and turn local competition into national, etc.” (Marx 1847, 423). “[N]o improvement of machinery, no appliance of science to production, no contrivances of communication, no new colonies, no emigration, no opening of markets, no free trade, nor all these things put together, will do away with the miseries of the industrious masses; but that, on the present false base, every fresh development of the productive powers of labour must tend to deepen social contrasts and point social antagonisms” (Marx 1864, 9).

On the other hand, Marx argues that modern technologies can be appropriated and transformed. So for example, he writes that the worker’s “appropriation of his own general productive power” (Marx 1857/58, 705) has the potential to foster “the general reduction of the necessary labour of society to a minimum, which then corresponds to the artistic, scientific etc. development of the individuals in the time set free, and with the means created, for all of them” (Ibid., 706).

Marx stresses that there is a dialectic of society’s temporal and spatial aspects and the development of technology and communications (the means of communication). Technologies do not develop arbitrarily. In class societies, their emergence is shaped by particular interests and power structures. At the same time, technology development and use is not determined, but also has a degree of unpredictability.

Capitalism reaches

spatial and temporal limits that it tries to overcome in order to avoid crisis

and continue accumulation. “Capital is the endless and limitless drive to go

beyond its limiting barrier” (Marx 1857/58, 334).

Capital accumulation requires: 1) labour power; 2) means of production (raw

materials, technologies, infrastructure); 3) commodity markets; 4) capital and

capital investment. Globalisation and imperialism are strategies to cheapen the

access to labour power and means of production, as well as to gain access to

new commodity markets and opportunities for capital export and capital

investment. New transport and communication technologies are medium and outcome

of the globalisation of capitalism: The “revolution in the modes of production

of industry and agriculture made necessary a revolution in the general

conditions of the social process of production, i.e. in the means of

communication and transport. […] the means of communication and transport

gradually adapted themselves to the mode of production of large-scale industry

by means of a system of river steamers, railways, ocean steamers and

telegraphs” (Marx 1867, 505-506). It is no accident

that the Internet became so important in a new phase of the globalisation of

capitalism.

The globalisation of production lengthens the turnover time of capital, the total time it takes to produce and sell commodities, because the commodities have to be transported from one place to another. As a consequence, capitalism strives to develop technological innovations in transport and communications in order to speed-up the production and distribution of commodities and the circulation of capital. “Economy of time, to this all economy ultimately reduces itself” (Marx 1857/58, 173).

Capitalism is shaped by the drive to expand and accumulate capital and power. Capitalism’s inherent imperialistic character requires that the exploitation of labour, commodity sales, and political rule are organised across spatio-temporal distances. Capitalism therefore advances the development of technologies that allow the organisation of capitalism by traversing long spatial distances in short time. In addition, there is a capitalist tendency of acceleration. Acceleration is based on the principle of accumulating more economic, political and cultural power in less time. Acceleration means that more commodities are produced and consumed, more decisions made and more experiences organised in ever less time.

As a tendency, the capitalist logic of accumulation calls forth processes of acceleration, globalisation, and financialisation as capitalist strategies and what David Harvey (2003) terms temporal, spatial and spatio-temporal fixes that aim at temporarily overcoming capitalism’s inherent crisis tendencies. “The spatio-temporal 'fix' […] is a metaphor for a particular kind of solution to capitalist crises through temporal deferral and geographical expansion” (Harvey 2003, 115). Capitalism tends to defer crises geographically and into the future, but again and again reaches its limits that express themselves as crises. The development of new technologies is embedded into the search for spatio-temporal fixes to capitalism’s immanent crisis tendencies.

The transport of humans, information, and commodities is a key feature of capitalism. The means of transport and the means of communication therefore play a significant role in the organisation of accumulation. The following quotes show the importance that Marx gives to the phenomenon of the “shortening of time and space by means of communication and transport” (Marx 1865, 125):

“If the progress of capitalist production and the consequent development of the means of transport and communication shortens the circulation time for a given quantity of commodities, the same progress and the opportunity provided by the development of the means of transport and communication conversely introduces the necessity of working for ever more distant markets, in a word, for the world market. The mass of commodities in transit grows enormously, and hence so does the part of the social capital that stays for long periods in the stage of commodity capital, in circulation time – both absolutely and relatively. A simultaneous and associated growth occurs in the portion of social wealth that, instead of serving as direct means of production, is laid out on means of transport and communication, and on the fixed and circulating capital required to keep these in operation” (Marx 1885, 329)

“The main means of cutting circulation time has been improved communications” (Marx 1894, 164).

“The more production comes to rest on exchange value, hence on exchange, the more important do the physical conditions of exchange – the means of communication and transport – become for the costs of circulation. Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier. Thus the creation of the physical conditions of exchange – of the means of communication and transport – the annihilation of space by time – becomes an extraordinary necessity for it. Only in so far as the direct product can be realized in distant markets in mass quantities in proportion to reductions in the transport costs, and only in so far as at the same time the means of communication and transport themselves can yield spheres of realization for labour, driven by capital; only in so far as commercial traffic takes place in massive volume – in which more than necessary labour is replaced – only to that extent is the production of cheap means of communication and transport a condition for production based on capital, and promoted by it for that reason” (Marx 1857/58, 524-525).

Marx not just describes the importance of the means of communication in capitalism, but also how the production of knowledge and communication develops due to capitalism’s need to increase productivity. Increasing productivity requires scientific progress and expert knowledge in production. The rising importance of knowledge and communicative labour is a consequence of the capitalist development of the productive forces. Marx in the Grundrisse anticipated the emergence of what some today term informational capitalism or digital capitalism or cognitive capitalism. He speaks in this context of the general intellect: “The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, then, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and been transformed in accordance with it” (Ibid., 706).

Also in Capital, Marx stresses the importance of the communication industry for capitalism. He argues that the “communication industry” that focuses on “moving commodities and people, and the transmission of mere information – letters, telegrams, etc.” is “economically important” (Marx 1885, 134). He writes that there are capitalists who “draw the greatest profit from all new development of the universal labour of the human spirit” (Marx 1894, 199). Today, these capitalists are CEOs, managers, and shareholders of transnational communication corporations such as Apple, AT&T, Verizon, Microsoft, China Mobile, Alphabet/Google, Comcast, Nippon, Softbank, IBM, Oracle, Deutsche Telekom, Amazon, Telefónica, etc.

Theories of the information society, whose ideal-type is Daniel Bell’s (1976) approach, claim that information production has become dominant in the economy and has radically transformed society into a new formation. Marxists are often critical of such claims that entail the danger of overlooking and downplaying the continuities of capitalism. Consequently, neoliberal ideologues often celebrate new technologies as radically transforming everything towards the better. But in wanting to avoid technological determinism and idealism, Marxists often simply ignore the role of communications technologies and information production in the economy and society. The point is that today we experience the interaction of many capitalisms, including digital capitalism, communicative capitalism, finance capitalism, mobility capitalism, hyper-industrial capitalism, etc. (Fuchs 2014, Chapter 5).

Autonomist Marxism, especially the version advanced by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, has based on the notion of Marx’s general intellect stressed the rise of knowledge in capitalism. “General intellect is a collective, social intelligence created by accumulated knowledges, techniques, and knowhow. The value of labor is thus realized by a new universal and concrete labor force through the appropriation and free usage of the new productive forces. What Marx saw as the future is our era” (Hardt and Negri 2000, 364). “Just as in a previous era Lenin and other critics of imperialism recognized a consolidation of international corporations into quasi-monopolies (over railways, banking, electric power, and the like), today we are witnessing a competition among transnational corporations to establish and consolidate quasi-monopolies over the new information infrastructure” (Ibid., 300). Hardt and Negri are among the limited number of radical theorists who have taken the role of communication in capitalism serious.

Marx was also visionary in respect to the emergence of the Internet. He envisioned a system that enables establishing “interconnections”, where “each individual can acquire information about the activity of all others and attempt to adjust his own accordingly”, and “connections are introduced thereby which include the possibility of suspending the old standpoint” (Marx 1857/58, 161). Doesn’t Marx here give a perfect description of the Internet? Can we say that Karl Marx invented the Internet?

Another important contribution that Marx made to ground foundations of a critical theory of communication is his critique of ideology.

4. Ideology as Fetishised Communication, Fetishism as Ideological Communication

Marx critically theorised ideology and practiced the ideology critique of religion, bourgeois thought and capitalism. In his very early works, he stressed that ideologies create illusions and deceive and criticised religion as ideology:

“Religion is the sigh

of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the

spirit of spiritless conditions. It is the opium of the people. To

abolish religion as the illusory happiness of the people is to demand

their real happiness. The demand to give up illusions about the existing

state of affairs is the demand to give up a state of affairs which needs

illusions” (Marx 1844b, 175-176).

For Marx, the belief in religion is an ideological expression of a dominative society. He criticised left-wing thinkers such as Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Feuerbach for stopping at the critique of religion and not seeing how it is related to capitalism and necessitates the critique of capitalism. For Marx, “the criticism of heaven” has to turn “into the criticism of the earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics” (Ibid., 176).

The German Ideology is a draft book that Marx and Engels wrote for gaining self-understanding of the contemporary German philosophy and left-wing critique of their time. In the German Ideology, Marx argues that in “all ideology men and their relations appear upside-down as in a camera obscura” and that “this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 36). It here becomes evident that Marx conceives ideology based on Hegel’s dialectic of essence and appearance: Ideologies make existence appear different from how it really is. It hides the true essence and state of the world behind false appearances and communicates these false appearances as truths and nature. Ideology makes being appear as immediate, but illusionary reality whose simplicity hides the underlying complexity of the world that cannot always be experienced directly. Hegel (1991, Addition to §112), argues that the “immediate being of things is […] represented as a sort of rind or curtain behind which the essence is concealed”. For Hegel, the truths hidden behind appearances are part of the world’s logic. In contrast, for Marx the process of hiding, naturalising, concealing and making truth disappear is an immanent expression of and practice in class societies.

In Capital, Marx (1867, 163-177) developed the insight that ideology hides power relations and naturalises domination into the concept of commodity fetishism. The commodity is a “mysterious” and “a very strange thing” (Ibid., 163). “The mysterious character of the commodity-form consists therefore simply in the fact that the commodity reflects the social characteristics of men's own labour as objective characteristics of the products of labour themselves, as the socio-natural properties of these things. Hence it also reflects the social relation of the producers to the sum total of labour as a social relation between objects, a relation which exists apart from and outside the producers. Through this substitution, the products of labour become commodities, sensuous things which are at the same time supra-sensible or social” (Ibid., 164-165).

The very structure of capitalism makes commodities, capital, money, classes, etc. appear as natural properties of society. Because of the division of labour and the mediated character of capitalism, producers and consumers do not directly experience the whole production process of the commodity. In everyday capitalist life, we are primarily confronted with commodities and money as things, whereas the production process and its class relations remain hidden. Capitalism is thereby in itself ideological in the very practices of capitalist production. Fetishism is ideological just like ideology is fetishist: Ideology fetishises certain changeable social relations as static, unchangeable, natural, thing-like entities.

The commodity is bound up with a peculiar capitalist form of language and communication: “Commodities as such are indifferent to all religious, political, national and linguistic barriers. Their universal language is price and their common bond is money” (Marx 1859, 384). In Capital, Marx argues that the commodity’s price (the monetary expression of a commodity’s average value) and value are the commodity’s language:

“We see, then, that everything our analysis of the value of commodities previously told us is repeated by the linen itself, as soon as it enters into association with another commodity, the coat; Only it reveals its thoughts in a language with which it alone is familiar, the language of commodities. In order to tell us that labour creates its own value in its abstract quality of being human labour, it says that the coat, in so far as it counts as its equal, i.e. is value, consists of the same labour as it does itself. In order to inform us that its sublime objectivity as a value differs from its stiff and starchy existence as a body, it says that value has the appearance of a coat, and therefore that in so far as the linen itself is an object of value [Wertding], it and the coat are as like as two peas. Let us note, incidentally, that the language of commodities also has, apart from Hebrew, plenty of other more or less correct dialects. The German word ‘Wertsein' (to be worth), for instance, brings out less strikingly than the Romance verb ' valere', ‘valer', ‘valoir' that the equating of commodity B with commodity A is the expression of value proper to commodity A” (Marx 1867, 143-144).

Price information communicates the value of a commodity. Capitalism has its particular form of capitalist communication, in which things appear to speak to humans. The sales process is a de-humanised form of communication, in which humans do not interact with each other, but the commodity speaks to humans through its price and advertising. The commodity form is a capitalist medium of communication that because of its fetishist character hides the social relations and power structures, in which humans communicatively produce and productively communicate and constitute and reproduce class relations and exploitation. The commodity form is a reifying and fetishistic form of communication that speaks to humans in categories of things and prices of things. Horst Holzer (1975, 45) stresses in this context that the “communicative character of commodities and the commodity character of communication” form the “foundation of an illusory synthesis at the level of society as a whole”. The commodity form not just communicates prices, but also communicates that the commodity and capital are the natural organisation forms of society as a whole. Given the reified and alienated status of the commodity in capitalism, the commodity form of communication (advertising as audience/user commodity, communicative labour-power as commodity, access to information and communication as commodities, communicative contents as commodities, communication technologies as commodities, etc.) can also appear as natural properties of communication.

“The social relations of production embedded in goods are systematically hidden from our eyes. The real meaning of goods, in fact, is emptied out in capitalist production and consumption” (Jhally 2006, 88). Capitalist production through the fetishism of commodities empties out the real meaning of commodities and renders the real communication processes and their power structures that organise commodity production invisible. Advertising is a form of fetishised communication that gives and communicates artificial meanings to commodities. “Production empties. Advertising fills” (Ibid., 89). Advertising is so powerful because it tells commodity stories and provides meanings about goods and the economy. It uses various strategies for doing so, e.g. black magic, a commodity communication strategy, where “persons undergo sudden physical transformations” or “the commodity can be used to entrance and enrapture other people” (Ibid., 91). “The real function of advertising is not to give people information but to make them feel good” (Ibid.). Advertising is a secular form of religion, a magic communication system (Williams 1980). Advertising is a system of commodity fetishism: It promises satisfaction and happiness through the consumption of things (Jhally 2006, 102). Advertising is propaganda that promotes the ideology of human happiness through consumption of commodities. But advertising is not just a form of ideological communication that acts as commodity propaganda. It is also a peculiar commodity itself that is produced through the exploitation of audiences’ and users’ labour that creates attention and data (Smythe 1977; Fuchs 2014; 2015).

In his Comments on James Mill’s “Elements of Political Economy”, Marx (1844a) makes clear that the language of commodities is not a true form of communication, but an alienated and alienating type of communication characteristic for capitalism. In capitalism, language and communication are ideologically deformed, fetishising and naturalising:

“The only intelligible language in which we converse with one another [in capitalism] consists of our objects in their relation to each other. We would not understand a human language and it would remain without effect. By one side it would be recognised and felt as being a request, an entreaty, and therefore a humiliation, and consequently uttered with a feeling of shame, of degradation. By the other side it would be regarded as impudence or lunacy and rejected as such. We are to such an extent estranged from man's essential nature that the direct language of this essential nature seems to us a violation of human dignity, whereas the estranged language of material values seems to be the well-justified assertion of human dignity that is self-confident and conscious of itself” (Marx 1844a, 227).

For Marx, the fetishist character of language and communication in capitalism is not limited to the economy, but extends itself into the realms of politics and culture, where the state, bureaucracy, the ruling parties, the nation, nationalism, wars, racism, etc. appear through ideologies as natural forms of human communication and society. So whereas an economic form of ideology operates in the commodity’s and capital’s social form, we also find political ideologies in capitalism that act in a fetishist manner and in doing so aim at justifying dominant group’s rule and distract attention from how capitalism and domination are at the heart of inequalities and other problems of society.

The most significant ideological and societal shift that societies around the world face today is the emergence of new nationalisms. In contemporary capitalism, neoliberal capitalism has turned into new authoritarian capitalisms signified by new nationalisms and political phenomena such as Donald Trump (USA), Brexit, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (AKP, Turkey), Viktor Orbán (Fidesz, Hungary), Heinz Christian Strache (Freedom Party of Austria), Norbert Hofer (Freedom Party, Austria), Sebastian Kurz (Austrian People’s Party), the Alternative for Germany (Germany), Narendra Modi (Bharatiya Janata Party, India), Rodrigo Duterte (PDP-Laban, Philippines), Marine Le Pen (National Front, France), Geert Wilders (Party for Freedom, The Netherlands), Nigel Farage (UK Independence Party), Jarosław Kaczyński (Law and Justice Party, Poland), Andrej Babiš (Action of Dissatisfied Citizens, Czech Republic), the Finns Party (Finland), Golden Dawn (Greece), Jobbik (Hungary), the Danish People’s Party, the Sweden Democrats, etc. The analysis of new forms of authoritarian capitalism is a key task for a Marxist theory of communication and ideology today. It has to involve an analysis of the structure of ideology, the way it is communicated over various media, including not just traditional ones (newspapers, speeches, television, radio), but also mobile media, social media and the Internet, its societal causes, and social struggles that could constitute alternatives.

Features of right-wing authoritarianism include hierarchic leadership, the friend/enemy-scheme, the friend-enemy-scheme, patriarchy, and the belief in militarism and law and order as means for responding to conflicts (Fuchs 2018). Right-wing authoritarian ideology involves the presentation of refugees, immigrants, foreigners, foreign states, or other groups as enemies of the nation that threaten its social cohesion and/or culture. Nationalism is an ideology that constructs a fictive national unity of capital and labour by opposing the nation to a foreign enemy and thereby distracts attention from how social problems are grounded in class, exploitation and domination. Nationalism is a “misty veil” that “conceals in every case a definite historical content” (Luxemburg 1976, 135). Nationalism is a political fetishism that communicates the nation in the form of a “we”-identity (a national people) that is distinguished from enemies (outsiders, other nations, immigrants, refugees, etc.) that are presented as intruders, aliens, sub-humans, parasites, uncivilised, etc.

Marx did not limit the analysis of ideology and fetishism to the economy, but also criticised political fetishisms such as nationalism. So for example in 1870, he discussed the role of nationalism in distracting attention from class struggle and benefiting the ruling class. He analysed the creation of false consciousness among the working class in one country so that it hates immigrant workers and workers in the colonies. He specifically addressed that question in respect to Ireland as a British colony:

“Ireland is the BULWARK of the English landed aristocracy. The exploitation of this country is not simply one of the main sources of their material wealth; it is their greatest moral power. […] And most important of all! All industrial and commercial centres in England now have a working class divided into two hostile camps, English PROLETARIANS and Irish PROLETARIANS. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who forces down the STANDARD OF LIFE. In relation to the Irish worker, he feels himself to be a member of the ruling nation and, therefore, makes himself a tool of his aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He harbours religious, social and national prejudices against him. […] This antagonism is kept artificially alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short by all the means at the disposal of the ruling class. This antagonism is the secret of the English working class's impotence, despite its organisation. It is the secret of the maintenance of power by the capitalist class. And the latter is fully aware of this” (Marx 1870, 473, 474, 475).

For Marx, overcoming ideology requires overcoming capitalism, class society, exploitation, and domination.

5. Conclusion

In Marx’s works, there is a number of important elements of a critical theory of communication, including the following ones:

Communication is a material process, in which humans produce and reproduce social relations, social structures, social systems, groups, organisations, institutions, society, and sociality.

Society is possible because it is based on the social character of language and communication and the communicative character of social relations.

Communication has both economic and non-economic features.

Marx opposed technological determinism by a dialectic of technology and society that sees technology (including the means of communication) as having a contradictory character in class societies.

Technologies do not develop arbitrarily. In class societies, their emergence is shaped by particular interests and power structures. At the same time, technology development and use is not determined, but also has a degree of unpredictability.

Marx stressed that there is a dialectic of society’s temporal and spatial aspects and the development of technology and communications (= the means of communication).

With the notion of the general intellect, Marx anticipated the emergence of communicative/informational/digital/cognitive capitalism.

Marx critically theorised ideology as fetishist form of communication. Ideology hides the true essence and state of the world behind false appearances and communicates these false appearances as truths and nature.

Capitalism has its particular form of capitalist communication, in which things appear to speak to humans. The sales process is a de-humanised form of communication, in which humans do not interact with each other, but the commodity speaks to humans. The language of commodities is not a true form of communication, but an alienated and alienating type of communication characteristic for capitalism.

The fetishist character of language and communication in capitalism is not limited to the economy, but extends itself into the realms of politics and culture, where the state, bureaucracy, the ruling parties, the nation, nationalism, wars, racism, etc. appear through ideologies as natural forms of human communication and society.

Struggles for socialist alternatives are struggles for “the positive transcendence of private property as human self-estrangement”, “the real appropriation of the human essence by and for man”, “the complete return of man to himself as a social (i.e., human) being”, “humanism”, “the true resolution of the strife between existence and essence, between objectification and self-confirmation, between freedom and necessity, between the individual and the species” (Marx 1844c, 296).

Such a society would be a true communication society, in which social relations would not be shaped by asymmetric power structures and exploitation, but controlled by the community of humans who act, produce, decide and live in common based on the common control of society. Commons-based communication means to make something common to a community. It is a process of commoning.

The term communication in modern language is derived from the Latin verb communicare and the noun communicatio. Communicare means to share, inform, unite, participate, and literally to make something common. A heteronomous and class-divided society is a society based on particularistic control. Struggles for the commons in contrast aim at overcoming class and heteronomy and to make society a realm of common control. In an economy of the commons, the means of production are owned collectively. In a polity of the commons, everyone can directly shape and participate in collective decision-making. In a culture of the commons, everyone is recognised. In such a participatory democracy, humans speak and communicate as a common voice. They own and decide together and give recognition to each other.

A communicative society is not a society in which humans communicate because humans have to communicate in all societies in order to survive. A communicative society is also not an information society, in which knowledge and information/communication technologies have become structuring principles. A communicative society is a society, in which the original meaning of communication as making something common is the organising principle. Society and therefore also communication’s existence then correspond to communication’s essence. A communicative society is a society controlled in common so that communication is sublated and turned from the general process of the production of sociality into the very principle on which society is founded. A communicative society also realises the identity of communicare (communicating, making common) and communis (community). Society becomes a community of the commons. Such a society is a commonist society. Commons-based media enable communication whose “primary freedom […] lies in not being a trade” (Marx 1842, 175).

References

Bell, Daniel. 1976. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. New York: Basic Books.

Fuchs, Christian. 2015. Culture and Economy in the Age of Social Media. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Digital Labour and Karl Marx. New York: Routledge.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, David. 2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jhally, Sut. 2006. The Spectacle of Accumulation. Essays in Culture, Media, & Politics. New York: Peter Lang.

Luxemburg,

Rosa. 1976. The National Question: Selected Writings. New York: Monthly

Review Press.

Marx,

Karl. 1894. Capital Volume Three. London: Penguin.

Marx,

Karl. 1885. Capital Volume Two. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital Volume One. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1865. Value, Price and Profit. In MECW Volume 20, 101-149. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Marx, Karl. 1857/58. Grundrisse. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1847. Wages. In MECW Volume 6, 415-437. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Marx, Karl. 1844a. Comments on James Mill, Élémens d’economie politique. In MECW Volume 3, 211-228. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Marx, Karl. 1842. Proceedings of the Sixth Rhine Province Assembly. First Article. Debates on Freedom of the Press and Publication of the Proceedings of the Assembly of the Estates. In MECW Volume 1, 132-181. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Mehring, Franz. 2003/1936. Karl Marx: The Story of His Life. Abingdon: Routledge.

Stalin,

Joseph V. 1972. Marxism and the Problems of Linguistics. Peking: Foreign

Languages Press.

Williams, Raymond. 1989. What

I Came to Say. London: Hutchinson Radius.

Williams,

Raymond. 1980. Culture and Materialism. London: Verso.

Williams,

Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

About the Author

Christian Fuchs is a critical theorist of communication and society. He is co-editor of the journal tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique and a professor at the University of Westminster. @fuchschristian http://fuchs.uti.at

Translated from German. German original: „Wie ein heller Sonnenstrahl, der durch düstere und scheinbar undurchdringliche Wolkenschichten bricht, so lenkt heute der hundertste Geburtstag von Karl Marx unseren Blick aus einer grauenvollen Gegenwart in eine hellere Zukunft [...] die rast- und ruhelose Kritik [...] ist seine wirkliche Waffe gewesen [...] So fortzuarbeiten auf den unzerstörbaren Grundlagen, die er gelegt hat, ist die würdigste Huldigung, die wir [...] [ihm] an seinem hundertsten Geburtstage darbringen können“.

Translated from German. Original: „Stalin bemerkt an der

Sprache vornehmlich nur ihre zeichenhaft technische, ihre phonetisch-morphologische,

also ihre relative starre Seite. Hingegen ist sein dialektisch

ungeschultes Auge nicht in der Lage, das, was man sehr unzulänglich die

‚Stilistik’, etwas besser das ‚Leben’ der Sprache bezeichnet hat, in

ihrer vollgültigen, ja das wahre Wesen der Sprache ausmachenden Bedeutung zu

erkennen. In seiner Schrift wird diese Seite der Sprache vollkommen

vernachlässigt. In diesem ‚Leben’ liegt aber das veränderliche, weil ideologische,

oder besser das ideologische und deshalb zwangsläufig veränderliche

Moment der Sprache. Technik und Leben der Sprache verhalten sich zueinander wie

Form und Inhalt”.