Abstract: New communication technologies strengthen existing power relations, helping to maintain class inequalities and alienating people. In the new communication age, human subjectivity itself has become a commodity. This paper analyses the role of Marxist studies in the academic field of communication studies. It focuses on the relevance of Marx's views for understanding communication in the digital era, Marxist communication studies after the expansion of digital media, and new dimensions of communication that have been incorporated into Marxist literature. Topics that matter in this context include the intersection of play and work, media economics in the age of digital communication, digital labour, the online games industry, targeted advertising, newly emerging social inequalities, and surveillance and privacy issues. Also an outlook for potential future Marxist studies of communication is given.

Keywords: communication studies, digital capitalism, digital media, Marx, Marxist studies

Acknowledgement: The author thanks Christian Fuchs for his valuable suggestions and contributions.

1.

Introduction:

Is There A Trend Towards Marxist Studies?

“We're dreaming again about the future,

by lifting our eyelashes from our toes,

we’re looking into the mountains, horizons, clouds.”

Şükrü Erbaş, Aykırı Yaşamak

Marx's approach remains the most important theory for criticising contemporary society. Changes in the last century have made Marx's theory even more important. Since the 1800s, Marx's works have influenced many disciplines. Communication studies is one of these fields. While in Capital, Grundrisse, and other works, communication is not considered as a separate topic, Marx focuses on issues such as communication, technology, and even automation. Although of course digital labour did not matter during his own time, Marx's views have a central significance in understanding this phenomenon today. Marx argued that capital has the inherent tendency to substitute labour by machines and that this will not be to the benefit of workers, but serves the profit interest of capital. Digitalisation has transformed the whole of society, and accordingly it has also transformed communications. Every stage of communication, from the production process of information to an audience’s reception process, has changed. This transformation has left many journalists out of business, has brought the concept of unpaid labour to the forefront, and has turned users into commodities.

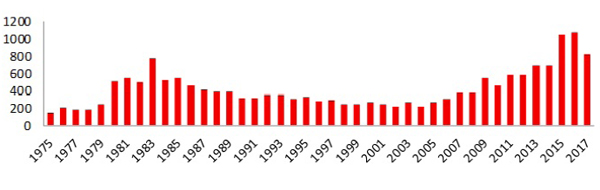

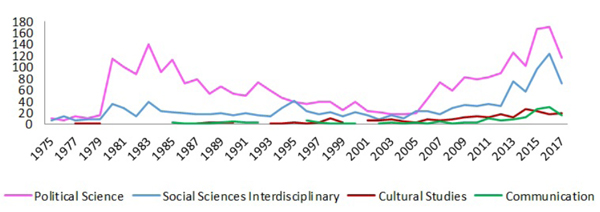

Data from Web of Science[1] covering articles, book reviews, proceeding papers, editorial materials and reviews shows that there are 17,998 articles published between 1975 and 2017 that mention “Marx”, “Marxism” or “Marxist theory” in their title or abstract. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, when looking at the number of Marxist articles published since 1975, there was a significant increase in some periods. However, it seems that this volume also diminished from time to time. In the 1970s and in the late 1990s, there was a relatively low level of Marxist publications indexed in Web of Science. Fuchs (2014a, 269) argues that the rise of neoliberalism, commodification, the rise of post-modernism, the lack of trust in alternatives to capitalism, and the relatively low presence and intensity of socio-economic struggles influenced the conditions for conducting Marxist studies.

The data obtained from Web of Science indicates that there has been an increase in the number of articles that mention “Marx”, “Marxist theory” or “Marxism” in two periods – the 1980s and the post-2008 period. The interest that has taken place since 2008 can be explained both by the role the political-economic crisis of capitalism and the increased relevance of digital technology. It can be said that the economic crisis that started in 2008 might have resulted in an increase of the critique of the capitalist system. According to Vincent Mosco (2012, 570), “the global economic crisis that filled the headlines beginning at the end of 2008 led to a resurgence of popular interest in the work of Karl Marx”. Although the number of Marxist articles has in recent years increased in comparison to previous ones, there are studies showing the ratio of Marxist to non-Marxist studies. İrfan Erdogan (2012, 354-357) analysed academic articles that were published between 2007 and 2011 and found that 210 articles out of 1,010 mentioned Marx’s name. The share of those using a Marxist methodology (excluding post-Marxism) was only 7.3%.

Figure 1: Annual number of articles that mention “Marx”, “Marxist theory” or “Marxism” in their title or abstract. Data source: Web of Science, 1975-2017

Even though Marxist approaches only account for a small portion of all published knowledge, it is evident that Marxist studies’ relevance has increased in recent years. The power of capital continued to advance during the 2000s (Schiller 2000; Jameson 2011). One reason for this is that new communication technologies are strengthening existing power relations, helping to maintain class inequalities and alienating humans. In the new communication age, humans’ subjectivity has become a commodity. According to data from Web of Science, since 2015 there has been a dramatic increase of the number of studies that mention “Marx”, “Marxist theory” or “Marxism”. The Marxist analysis of digital media and digital labour may have contributed to this trend.

Figure 2: Annual number articles from various academic disciplines that mention “Marx”, “Marxist theory” or “Marxism” in their title or abstract, data source: Web of Science, 1975-2017

There are also other developments that may indicate an increased interest in Marxist studies within the social sciences. Conferences such as “Digital Labour: Workers, Authors, Citizens”; the 4th ICTs and Society Conference, “Critique, Democracy and Philosophy in 21st Century Information Society: Towards Critical Theories of Social Media”; the 5th ICTs and Society Conference, “the Internet and Social Media at a Crossroads: Capitalism or Commonism? Perspectives for Critical Political Economy and Critical Theory”; the 6th ICTs and Society Conference, “Digital Objects, Digital Subjects: An Interdisciplinary Symposium on Activism, Research & Critique in the Age of Big Data Capitalism”; or the 13th Conference of the European Sociological Association, “(Un)Making Europe: Capitalism, Solidarities, Subjectivities” were just some of these conferences. In the context of communication studies, the journal TripleC has been a platform for Marxian studies and has also featured special issues dedicated to that topic.

2.

Foundations

of Marxist Communication Studies

Since

Marx’s

first works which were published in the 1840s, the Marxist literature

has also been the basis for the work of communication. Marx (1993/1858,

524) argues:

“Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier. Thus the creation of the physical conditions of exchange – of the means of communication and transport the annihilation of space by time – becomes an extraordinary necessity for it. Only in so far as the direct product can be realized in distant markets in mass quantities in proportion to reductions in the transport costs, and only in so far as at the same time the means of communication and transport themselves can yield spheres of realization for labour”.

This passage indicates that communication is a tool of commodification. Horst Holzer (2017, 712) suggests that capital is interested in the press market and that the audience market needs a medium that helps propagate the capitalist system in the form of advertisements. For this reason, communication should be taken into account when analysing capitalist society. Likewise, Benedict Anderson (1991, 37) argues that the press strengthens the capitalist system and that the phase of what he terms print capitalism constitutes the origin of capitalism.

Academics in the fields of communication and cultural studies have conducted a variety of studies that are based on Marx's approach. From 1923 onwards, the Frankfurt School’s thinkers, including Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse and Benjamin, used a Marxist framework to criticise capitalist society. In Dialectic of Enlightenment, Horkheimer and Adorno (2002) emphasise that the Enlightenment that criticised dogmatisms became dogmatic and in a negative dialectic turned against itself. In addition, they introduced the concept of the culture industry that has had huge impact on the field of communication studies. Also Herbert Marcuse (2007, 14) analysed cultural products. He argued that cultural products reinforce false consciousness when they as commodities try to create one-dimensional thought and behaviour and a system in which ideas, aspirations and objectives are presented as fixed and unchangeable.

Massification and mass production was also an interest of Walter Benjamin (2008), whose essay on the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction emphasises that mechanical production changed the aura and the conditions of the work of art. In addition, thinkers such as Louis Althusser, Georg Lukács and Karl Korsch have also emphasised the importance of ideology and culture. According to Althusser (2014, 144), the media form an ideological state apparatus that is an important medium for the reinforcement of the capitalist system. Herman and Chomsky (2010, 2) argue that media play an important role in the manufacturing and reproduction of consent.

Georg Lukács and Karl Korsch, who helped develop Western Marxism, argued that culture and ideology are key domains of capitalism. Gramsci's thoughts on the concept of hegemony also made a contribution to the foundations of understanding communication. Thinkers such as Lee Artz, Christian Fuchs, Peter Golding, Wayne Hope, Ursula Huws, Armand Mattelart, Vincent Mosco, Robert W. McChesney, Eileen Meehan, Bernard Miège, Graham Murdock, Kaarle Nordenstreng, Dan Schiller, Herbert Schiller, Dallas Smythe, Colin Sparks, Janet Wasko, and Yuezi Zhao have made important contributions to the critical understanding of the political economy of communication. From the 1960s onwards, cultural studies has become one of the most influential approaches for studying communication. In the late 1970s, post-modernism emerged as an influential approach to the study of communication and culture. Fredric Jameson (1984) stresses that post-modernism is the cultural logic of late-capitalism. David Harvey (1990) added that postmodernism is an ideological manifestation of the emergence of capitalism’s flexible regime of accumulation. At the same time, capitalism has increasingly given rise to digital technologies. As a consequence, academics working in the field of communication studies have started to analyse digital capitalism.

3.

The

Relevance of Marx in the Era of Digital Capitalism

Digital media has become an important part of everyday life. Computers, the Internet, mobile devices, social networks and instant messaging have established new social realities. Progressive social change cannot automatically materialise itself on Facebook, YouTube or Twitter. It also requires social spaces where humans engage in face-to-face interaction and protest (Fuchs and Mosco 2016, 4).

Mobile devices and social networks do not automatically bring about social freedom. Although Marx lived in a different capitalist period, he advanced thoughts that anticipated digital capitalism. For example, in the Grundrisse, he discussed capital’s use of machines: “For capital, the worker is not a condition of production, only work is. If it can make machines do it, or even water, air, so much the better. And it does not appropriate the worker” (Marx 1993/1858, 498). He here stresses that capital’s purpose is profit and it treats workers and machines that substitute workers as a means to that end. What is most important to capital is making profit, rather than the state of the tools that help to make it.

Marx (Ibid., 520) wrote of “the invention of the spinning machine, which supplied a greater product in the same labour time, or, what is the same thing, required less labour time for the same product – less time delay in the spinning process”. Capital prefers a machine that produces an amount and value of commodities in less time to a number of workers who produce the same amount over a longer period of time. As a consequence, capital will yield more products in the same period of time. Marx (Ibid., 701) also wrote:

“Fixed capital, in its character as means of production, whose most adequate form [is] machinery, produces value, i.e. increases the value of the product […] Capital employs machinery, rather, only to the extent that it enables the worker to work a larger part of his time for capital, to relate to a larger part of his time as time which does not belong to him, to work longer for another. Through this process, the amount of labour necessary for the production of a given object is indeed reduced to a minimum, but only in order to realize a maximum of labour in the maximum number of such objects”.

Mechanisation benefits capital and extends the workers’ labour time: “The most developed machinery thus forces the worker to work longer than the savage does, or than he himself did with the simplest, crudest tools” (Ibid., 708-709). Moreover, Marx (Ibid., 739) says that if “capital could possess the machinery without employing labour for the purpose, then it would raise the productive power of labour and diminish necessary labour without having to buy labour. The value of the fixed capital is therefore never an end in itself in the production of capital”.

In Capital, there is a sentence that clearly summarises Marx’s views of labour: “An instrument of labour is a thing, or complex of things, which the worker interposes between himself and the object of his labour and which serves as a conductor, directing his activity onto that object” (Marx 1990/1867, 285). The era of digital capitalism has not reduced or done away with exploitation. In the digital era, digital communications is a means of intensifying labour and increasing the rate of surplus-value.

Martin Nicolaus, the English translator of the Grundrisse, writes in his foreword that Marx shows that the means of communication enrich not labour, but capital:

“Thus all the progress of civilization, or in other words every increase in the powers of social production, […] in the productive powers of labour itself – such as results from science, inventions, division and combination of labour, improved means of communication, creation of the world market, machinery etc. - enriches not the worker, but rather capital” (Nicolaus 1993, 21).

Antonio Negri (1993, 90) in his analysis of post-Fordist capitalism writes that

“[the] proletariat embodies a substantial section of the working class that has been restructured within processes of production that are automated, and computer controlled processes which are centrally managed by an ever-expanding intellectual proletariat, which is increasingly directly engaged in labour that is computer-related, communicative and in broad terms educative/formative”.

Inspired by the thoughts of Marx, many thinkers have analysed communication technology’s role in capitalism, domination and standardisation (see for example Horkheimer and Adorno 2002; Marcuse 2007; Benjamin 2008; Jameson 1984). According to Jameson (1984, 79), technology is not something that transforms society, but a medium that helps to maintain the status quo. Communications and networks are tools for the organisation of multinational capitalism.

Digital networks have added a whole new dimension of alienation by turning users’ subjectivity into a commodity. The producer becomes the product; targeted advertising is an important aspect of digital capitalism (see Fuchs 2017b, 2014c). When enrolling in social networks, users are sharing personal information and this data is used by advertisers to sell more products. Moreover, there are privacy violations in constant data surveillance. Communication studies scholars have started analysing such phenomena based on Marxist theory.

4.

Marxist

Communication Studies in the Age of Digital Media

Marxist communication scholars in the digital era are interested in a variety of topics including online advertising, online alienation, digital labour, digital capitalism, the intersection of play and labour (‘playbour’), digital monopolies, big data, the online game industry, digital inequalities, online surveillance, online privacy, nationalism online, racism online, digital communication in the context of class struggles, the digital commons, alternative online media, digital alienation, etc.

Dan Schiller argues that contemporary capitalism can best be characterised as digital capitalism (2011, 925). Marxist communication scholars have used the notion of digital labour for both paid and unpaid labour practices in the context of digital environments (Terranova 2000; Mosco and McKercher 2007; Manzerolle 2010; Fuchs 2010; 2014b; 2014c; 2014d; Fuchs and Sevignani 2013; Scholz 2013; Brown 2014; Pfeiffer 2014). According to Christian Fuchs (2014c, 351), digital labour is in fact alienated digital work. Labour is in capitalism alienated from itself, its instruments, objects and products.

The digital labour discourse is no longer just a debate limited to communication studies. It is also discussed within broader Marxist studies. For example, David Harvey (2017, 56-105) asserts that in advanced capitalist societies factory labour is replaced by other forms of labour, and digital labour is among them. Technology mediates digital labour that takes place everywhere. The difference between digital labour and other forms of labour is not only de-spatialisation: the dominant digital platforms are based on advertising and are generally characterised by unpaid labour and new forms of exploitation:

“What

was initially conceived as a liberatory

regime of collaborative production of an open access commons has been

transformed into a regime of hyper-exploitation upon which capital

freely

feeds. The unrestrained pillage by big capital (like Amazon and

Google) of the

free goods produced by a self-skilled labour force has become a major

feature

of our times. This carries over into the so-called cultural

industries”. (Harvey 2017, 96)

“It

is also interesting that some of the

most vigorous sectors of development in our times – like Google and

Facebook

and the rest of the digital labour sector – have grown very fast on

the back of

free labour”. (Ibid., 102)

In Assembly (2017), Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2017, 119-273) write about the changing composition of capital with reference to the digitalisation of labour. They suggest that labour is transformed by digital platforms that track users’ behaviour and generate web search hierarchies. Users create content without any payment, their content is sold to other users, and this process never stops. Users both produce and consume day and night. Another difference between digital labour and earlier forms of labour is the absence of a boss who imposes the division of labour. In digital labour, the division of labour is constituted by the relationships among users. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2017, 97- 98) say that “cooperative forms of social labour can and should be opened for common use.” This emphasis represents their argument about private property that “the common is not property”. Thus, if digital labour can be opened for common use, one of the main pillars of capitalism will eventually be removed.

A couple of other scholars within the field of communication studies have analysed digital alienation, which has become a prominent issue within Marxist communication studies (Andrejevic 2011; Comor 2010; Fuchs and Sandoval 2014; Krüger and Johanssen 2014). Advertising and branding are core features of the capitalist system today, which is why scholars are interested in this topic. Fuchs (2014b, 111) argues that advertising is one of the industries that is dominated by a huge amount of unpaid labour.

Advertising is also related to other phenomena, such as big data. Organising targeted advertising requires the generation, storage and processing of big data. Big data creates new ethical problems because of algorithms that enable and conduct surveillance. Fuchs (2017a; 2017b) argues that big data has emerged from the surveillance-industrial complex that combines state surveillance and corporate surveillance of digital data and the Internet. Big data serves surveillance, surveillance serves capitalism. Sebastian Sevignani (2017, 82) sees surveillance as an aspect of the commodification of information. “[M]ost politicians and corporate leaders believe that the future of capitalism lies in the commodification of information” (Barbrook 1998, 135). Targeted advertising is one of the mechanisms that keep the capitalist system going. It fosters sales and consumption and thereby the production of ever more commodities and ever newer commodities.

Users’ activities, sociality, knowledge, and networks become a product of their own work when they publish things on social media. Metaphorically, one can therefore say that the user has become a commodity. What is meant by this formulation is that human subjectivity has become ever more commodified and has reached the realm of human cognition and communication. Human subjectivity is also a use-value that enables social networking in online communities (Fuchs and Sevignani 2013, 259). The online game industry, MMORPGs and many other user-generated platforms are also transforming consumers into both prosumers and their subjectivity into commodities. Creating an avatar in an online game run by a for-profit company is unpaid labour. Online games are the most direct expression of the blurring line between labour and play. More generally speaking, neoliberal capitalism has turned free time into labour time and makes cultural labour appears as play, fun, and enjoyment. Increasingly, we no longer realise that we are workers and are exploited, because labour feels like fun.

According to Fuchs and Sevignani (2013, 261), the concept of inverse commodity fetishism is a term that defines people’s use of social media platforms and online games: on corporate social media, we do not experience the commodity, but only social interaction. The commodification of subjectivity is hidden behind the immediate social experience. Fuchs and Sevignani argue that classical commodity fetishism is inverted.

5.

The

Future of Marxist Communication Studies

Communication scholars will continue to study digital capitalism’s transformation. For doing so, basic texts, such as Marx’s works, will continue to be guiding lights for critical analysis. Douglas Kellner (2002, 31-41) argues that the works of Frankfurt School thinkers can be used to analyse communicative capitalism that has been dramatically shaped by new media and computer technologies. The culture industry, media capital, and digital technology mediates everyday life. Fuchs and Sandoval (2014, 515) also suggest that “critical theory can inform potential and actual struggles for a better world”. According to Fuchs and Sevignani (2013, 287), if William Morris and Herbert Marcuse lived today, they would criticise today’s digital media landscape, in which users predominantly consume the cultural works of celebrities and culture has not been democratised despite the false claims that we live in a participatory culture (see Fuchs 2017b, Chapter 3). Besides the works of Marx, the whole history and tradition of Marxist theory and Marxist cultural theory, starting with the work of Frankfurt School thinkers, can today be used as the main starting point for future studies (see Fuchs 2016). Fuchs (2014a), for example, argues that Dallas Smythe’s works are helpful in three ways. Smythe: a) reminds us of the importance of Marxism, b) stresses the distinction between administrative and critical research that is a crucial line of struggle in the time of neoliberalism and the new capitalist crisis, and c) puts forward a concept of the audience commodity that has informed the digital labour debate (see Fuchs 2014c; 2015). Marxist theory is the most important framework for analysing contemporary society and its communicative structures and practices.

Marxist studies allow us to show that the things that are thought to be real often do not really reflect the truth, but are ideological in character. So for example, according to Fuchs (2016, 172), users who claim that Facebook is great often only think about immediate individual advantages and fail to notice the role that digital exploitation and digital surveillance play in online communication.

Rapidly evolving technology and artificial intelligence continue to transform digital labour. In particular, we need more studies that empirically study the working conditions in the rapidly changing digital industries.

A Marxian analysis of communication should:

“[…] demonstrate how communication and culture are material practices, how labour and language are mutually constituted, and how communication and information are dialectical instances of the same social activity, the social construction of meaning. Situating these tasks within a larger framework of understanding power and resistance would place communication directly into the flow of a Marxian tradition that remains alive and relevant today”. (Mosco 2009, 44)

Fuchs (2014a, 284) argues that capital accumulation, class relations, domination and ideology and class struggle are key aspects of society today and its analysis.

6.

Conclusion

Marxist scholarship has gained new importance since 2008. The study of digital media, digital labour and other dimensions of digitality has become a significant aspect of Marxist studies. Marxism has to a significant degree shaped communication studies. Digitalisation, artificial intelligence and automation have resulted in the substitution of feelings by algorithmically generated information. The liquid relations that Bauman refers to in Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds (2013) have resulted in real relationships and feelings being replaced by liquid connections. Digitalisation does not merely affect emotions. It affects everything concerning humans and society. Benjamin’s (2008) work maintains its importance today as this age is witnessing unprecedented digital reproduction that is destroying originality. However, not only art, but also media products, culture and even human subjectivity have become commodities in the digital age.

Digitalisation has affected and transformed society in its totality. Marx's analysis of labour has become more important than ever. Along with the works of Marx, the whole history and tradition of Marxist theory should also be considered today in new ways in order to analyse the new dimensions of capitalism.

Analysing communication means analysing the production, circulation and consumption of information. A Marxist analysis of communication requires a focus on both labour and ideology. False consciousness has now become extreme false consciousness. The fact that humans love social media does not mean that they are not exploited. There is an ideological illusion that makes people who use social networks often think they are benefiting from these networks, although the economic benefits go to Google, Facebook, etc. without their noticing it.