1.

Introduction

Having

its origins in the 17th-century English and French utopian modes,

politically focused on pragmatism and optimism respectively (Racault

1991, 33-150), and initially rejected by the Marxist left before

being appropriated by philosophers like Ernst Bloch and Herbert

Marcuse in the 1960s (Monticelli 2018),

the utopian genre represents a reliable index of the capability of

societies to envision their best possible future. More specifically,

when understood as a product of humanism, the utopian genre attempts

to overcome the historical contradiction between intellectual autonomy

and political dependence (Balasopoulos

2008).

In this regard, the imposition of

capitalism’s own interpretation of such an overcoming has brought on a

decadence of the genre’s principles. As for the nature of utopia, the

insertion of videogames in this context is of semiotic interest in at

least two regards: as a form of expression, i.e. as a cybertextual

medium characterised by its singular expressive faculties, and as a

form of content, i.e. as an enunciable discursive device within the

limits allowed by its singularity as a medium.

This article has the purpose of answering two

specific questions: 1) can we strictly speak of the possible existence

of a link between utopia and videogames? and 2) what are the

possibilities offered by this link, in case it does exist, of

transcending the formalist conception of ludology?

To answer these

questions, this article is organised into the following sections: in

Section 2 (Background), the current state of the concept of utopia in

neoliberal society is estimated and its possibility is found in the

epistemological reality of game studies, consequently considered to have

inherited the cybernetic project of neoliberal society in that it was

collectively founded in the principles established by ludology. Finally,

the role that the cultural reason plays in capitalist societies and the

resignification, from the onset of economic liberalism, of said reason

as a means of escape are analysed. In Section 3 (Case and Methods), the

research question is found in the sociological problematic originating

from erasing the borders in the work-play relationship. Additionally,

two historical occasions in which videogames were focused around a

utopian purpose are referenced: procedural rhetoric videogames and

walking simulators.

In Section 4,

these variants of videogames – a style and a genre respectively – are

analysed in a separate manner in relation to the utopian potential of

the medium. In the first case, a critique of proceduralism is made based

on the enthymemic foundation of its proposal, the latter a result of its

strictly formalist structure. In the second, the reflective effect that

occurs in utopia when it refers to a dimension strictly belonging to

daily life is analysed. This effect takes place when it moves away from

the possibility of a global systemic change: a distinction is also made

regarding the sense in which this effect, while implying a

‘from-the-bottom-up’ construction, opposes the set goals and economic

performance-dominated formats. In Section 5 (Discussion and General

Conclusions), the research questions will be answered and discussed,

using the conclusions of each part of Section 4 as a reference.

2.

Background

Posing a question about the programming of utopia in the title of our

article is a statement of intent; indeed, such an enquiry demands that

videogames possess a degree of responsibility of a social, political,

and human complexion identical to that historically expected of

literature and film. Just as has been a fundamental objective of both

of these media, the goal of videoludic expression should be to

transcend the very form of the videogame by demonstrating an

integrated approach to human values, thereby participating in an

active form of humanism. Such a demand does not seek to bring the

expressive autonomy of videogames into question, nor does it intend to

put strain on their ontological nature or sustain such a nature at any

cost. We are aware of the theoretical resistance emerging from certain

sections of the game studies community, which are extremely

preoccupied with compartmentalising, delimiting, and prescribing

attempts to put videogames on a level with literary and filmic

experiences. Such resistance, always legitimate and

undoubtedly necessary in a specific moment in game studies history,

occurs especially in the ontological resource to ludology. The nature of

this resistance is drawn not from an intentional opposition, but instead

from the unintentional omission of the humanistic power –

which

this article considers a synonym of the narrative power – of the medium. As an example, the recent works by Juul (2013),

Costikyan (2013) or De Koven (2013)

represent an approach to videogames in their nature as a designed

artefact, undertaking their arguments in terms of rules and mechanics or

focusing on other types of purely formal aspects such as what is called

the “art of failure” (Juul 2013) or the value of

the “uncertainty” (Cosikyan 2013) of the

ludic execution. Differences aside, it would be quite surprising if in

the field of film studies there were a singular, never-ending debate

regarding eyeline match and off-camera, i.e. concerning an essential

part of cinema which, as such, cannot be renounced.

As far as we are aware, such opposition serves to highlight the

unconscious subordination of any kind of ideology to the market, a

common practice in the West that is prescribed by the capitalist

system. Indeed, game studies was founded in 2001 from a purely

formalist standpoint, with its foundational text written several years

previously (Aarseth 1997). The struggle to

distinguish videogames from other expressive media is not only

demonstrative of a legitimate academic position in the defence of this

new medium’s ontology; it is also a devastating victory for the

capitalist system. After all, surely the birth of an expressive medium

yielding tremendous profits and with universal reach is a capitalist

triumph? Indeed, it is a medium geared exclusively towards

entertainment, confined to its own form, distinct to any form of

reality, and, in consequence, locked in a perpetually non-critical

state. Moreover, is the articulation of a science in its name,

ludology, not an even greater triumph for capitalism, exhausting

itself in a perpetual reverberation of its own arguments over the

course of the past decade?

It is no secret that there is an inextricable link between videogames and

dystopia, the very antithesis of utopia, in which the alienation of

man is depicted in a wide range of ways. Nonetheless, this association

is not motivated by a critical spirit; instead, in such cases,

dystopia is used as a fictional façade. As Schell notes (2014),

videogames need to place characters in new contexts that can justify

the player’s learning of rules of the gameworld. Dystopia, despite

having become a recalcitrant common space for modern fiction, grants

this type of licence to the apocalypse, amnesia, or exile. In our

view, there is a fundamental distinction between utopia and dystopia;

as such, while utopia allows us to envisage situations that are

beneficial to humankind, starting from the current state of man’s

place in society, dystopia has a tendency to disconnect from this same

reality by representing stories with negative characteristics,

unconsciously inciting us to embrace the virtues of the current

system. Dystopia appears to enjoy its confinement to the realm of

videogames’ innocuous ideas; in contrast, utopia’s exile should

encourage us to value the present, unique force of the videogame

medium as a centrifugal expressive form, and not as a simple

centripetal entity. This is, of course, the objective of this article:

to reflect on the capacity of videogames to spread theories of a

better world from the inside out, starting with the world as it

currently is and, if possible, distinguishing the causes of its

successes or failures in this titanic task. Before delving deeper into

our investigation, we must begin by highlighting one of the factors

responsible for the present latency of utopia.

Capitalism

constructed

a never-ending range of possibilities based on money as quickly as it

consumed our real capacity to make decisions about our own existence;

to paraphrase Touraine (2001), we are

extras with serious difficulty in becoming protagonists. As Jameson (2005) affirms, adapting that famous phrase

uttered by Margaret Thatcher, there is no alternative to capitalism.

Once the collapse of the so-called ‘Second World’ threw its woes into

clear view, utopia – associated by some on the Western left with

Soviet communism – lost all its previous potential and prestige. This

defunct utopia gave rise to incalculable financial losses, millions of

lives lost at the hands of totalitarian terror, and environmental

degradation on an apocalyptic scale (Gray 2005).

Following its failure, we have been left alone with capitalism. As

such, only the new enemy of religious fundamentalism stands against

Western imperialism, though it does not articulate an anti-capitalist

thesis in doing so. This situation of mandatory imposition has been

explained by Fisher via the notion of capitalist realism. The

British-born writer and critic believes that there exists “the

widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political

and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine

a coherent alternative to it”

(2009, 2).

The system reigns supreme, bolstered by armies of consumers who have

confused the idea of progress with that of being on-trend. Man has

deserted his capacity to imagine future worlds in which the notions of

progress and wellbeing may once again possess a true meaning, the one

which was passed down by the fathers of the Enlightenment or the

proponents of UNESCO following the Second World War (Finkielkraut

1996). The roots of this desertion may well be found in the

global imposition of the free market in accordance with the model of

liberal Western democracies, an act that was difficult to replicate in

countries such as China and Russia owing to the idiosyncrasies of

their situations. The consequences have been as catastrophic as those

of the false communist utopia, resulting in tens of millions of

Chinese peasants being forced to become migrant labourers and millions

of people being excluded from work in the more advanced societies (Gray 2005). In these countries, the

materialisation of a global free market economy has not been

accompanied by institutional development or the extension of Western

values; in contrast, it has signalled the end of the epoch of global

Western supremacy and the advent of a point-of-no-return for past

levels of prosperity and social cohesion in the West (Gray

2005). Ultimately, free rein has been given to capitalism.

In this neoliberal and anarcho-capitalist epoch, the concepts of progress

and wellbeing possess a purely material meaning brought about by the

market’s excessive presence in our lives – and this will continue to

be the case owing to the unrelenting hypertrophy of capitalism as an

economic system. Its cyclical nature, infinite in character, is based

on the union of capital and its subsequent investment, with a desire

to accumulate profits that are then re-invested (Boltanski

and Chiapello 2002). It is no surprise that, in this context,

utopias are met with indifference and astonishment. Today, they have

been replaced by one supreme vocation: that of the machine wanting to

possess everything by means of money. In capitalism, needs have been

replaced by desires; such desires are not biological, but

psychological – and, like capitalism, they are infinite. From a

philosophical perspective, Deleuze and Guattari (1972)

warned that we are all machines in capitalism, a terrible connective

organism whose sole desire is production-produce, in which nature and

man are one and the same non-differentiated entity because the

distinction between them, which once defined our place in the world,

has been absorbed by the activity of machines that desire or produce.

Capitalism is a machine of infinite activity based on infinite

desires; unfortunately, our capacity to generate utopias has been

superseded by the belief that capitalism, in its execution of

never-ending sequences, will itself result in a superior state of

progress for humanity. This notion has eradicated the political

capital of utopia, relegating it to the realms of fantasy and of

science fiction.

It has been debated whether utopia pertains to the field of politics or

literature; as Jameson (2005) notes, utopia

as a genre has always been a political theme with a literary form.

Today, in any case, it is a solely literary concern. This definitive

displacement of the concept of utopia toward the cultural sphere, and

its fusion with the genres of fantasy and science fiction, is

demonstrative of two transcendental factors. Firstly, it shows the

existence of a separation between the economic, political, and

cultural spheres in capitalism. Bell (1996)

affirms that in capitalist society, these three spheres are governed

by contradictory principles, even if, historically, they were born

from the same impulse. For example, the bourgeoisie and experimental

art both expressed a mutual, unconditional rejection of each other,

despite having both emerged from their rebellion against the past. In

consequence, the principles that regulate these spheres are opposed;

where the economic sphere is concerned with efficiency, the political

sphere is concerned with the search for equality and the cultural

sphere with self-gratification. It is not difficult to imagine that

this triad of objectives would prove to be contradictory and result in

a perpetual source of conflict in capitalist societies. In the past,

it was possible to conceive a holistic definition of society, but this

is no longer the case. These three realms, albeit distinct, can

interact with each other but almost always act in accordance with

exclusive norms. In consequence, and in the second instance, the

present innocuousness of the utopian genre, now yet another member of

the ineffable and extensive cultural network of our societies, is

motivated by an exceptional fact. Indeed, though utopia (or any of the

other illustrious members of the cultural sphere) can be used to

critique aspects of the world associated with the other spheres, it

cannot modify the future behaviour of said spheres. Marcuse (1968)

noted how the unbridgeable gulf separating these three realms

provides, on one hand, necessary perspective for the cultural sphere

to act as a tool of critique and objection to any political or

economic factors, yet, on the other, condemns all its interventions to

be futile, relegating culture to a frivolous and trivialised space in

which the intersections with other spheres are non-operational.

A reassessment of this classic argument by the Frankfurt School can be

found in Jodi Dean’s works, expressed concretely in her notion of

communicative capitalism. The current situation, in which ideas and

political content are circulated through means other than those

offered by institutions, such as social networks or websites with

syndicated content (RSS), proves a paradoxical inoperability in

opposing the official political agenda and thus transforming the

environing reality via citizen activism, using these new media as a

support.

On the basis of the concept of communicative

capitalism, Bulut, Mejia and McCarthy (2014)

have analysed the online game Free Rice (developed by World Food Program, 2007-2018) under the critical

perspective known as “the rise of the ludic sublime”. Naturally,

videogames are acclaimed in neoliberal societies as a plausible

solution to complex political problems, forming part of the philintainment

practices. Nevertheless, as stated by the authors, Free Rice

depicts the abandonment of social problems by the states and

recalibrates the value of citizen participation in techno-consumerist

terms (2014, 347).

As Dean notes, the matters brought to the

public debate by the counterhegemonic model, among which these kinds

of games would be included, rarely find answers due to the abandonment

by official institutions of this function, hiding behind the existence

of this circulation of ideas:

Today, the

circulation of content in the dense, intensive networks of global

communications relieves top-level actors (corporate, institutional and

governmental) from the obligation to respond. Rather than responding to

messages sent by activists and critics, they counter with their own

contributions to the circulating flow of communications, hoping that

sufficient volume (whether in terms of number of contributions or the

spectacular nature of a contribution) will give their contributions

dominance or stickiness (Dean 2005, 53).

The most

immediate consequence of this phenomenon is that it renders culture

symbolic, that is, it places it in a metaphorical limbo that is

disconnected from the real world. Hauser (1969)

believed that artistic

forms of a symbolic nature principally develop in capitalist

societies, perhaps as a means of eluding any real critique of the

system. However, it is no surprise that an emancipated critique of

real issues flourishes in this context, an ‘other-worldly’ examination

focused on the formal investigation of works or the ludic element

concerning how the textual relations woven between them are

established. Is this not a fundamental definition of videogames: a

pure form so distinct from reality that it requires its own rules and

emphasises its ludic nature?

Coinciding with this social

mitosis, Hauser (1969) also observed that

since Romanticism; in other words, coinciding with the practice of

economic liberalism, the symbolic fictions of culture and of art have

become a means of compensating for the unlived, becoming valuable and

meaningful for individuals who had been unable, or who had not known

how, to make the most of their life’s journey. A discrepancy between

social function and aesthetic function is formed within us,

transforming cultural or artistic works into a microcosm used as a

refuge from our own life experience and, therefore, rendering it

materially separate from this same reality. The exacerbated use of

symbols in capitalist cultures – effectively a masking of reality –

implicitly carries with it an escape towards a fictitious world. This

idea of escape through fiction created by art or culture is an

aesthetic possibility that is completely alien to a pre-Romantic

conception of both of these realms. For Nietzsche, science was the

source of nihilism as it provoked the destruction of unreflexive

spontaneity in the world (Bell 1996). Today,

we can assert that it was, after all, capitalism, without a doubt a

concept that is in many aspects tied to science, which triggered a

definitive separation between culture, politics, and economics and

dealt the final blow to this irrational spontaneity. As a result, it

is no surprise that utopia, relegated to the cultural sphere, has

become a purely imaginary and fictional concept with no real

transcendence nor any transformative capacity.

On one hand, utopia is incapable of affecting the political and economic

realms, given that it pertains to the cultural sphere; on the other,

the enunciation of its discourse, transmitted via artistic media such

as literature, film, or videogames – featuring equally in this sphere

– is geared towards the creation of fictitious worlds bearing the

hallmarks of a refuge from this brave new neoliberal world that has

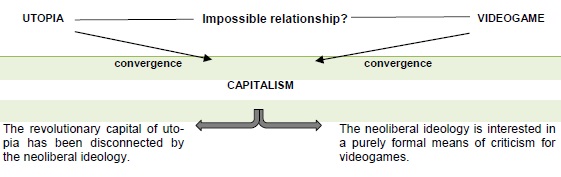

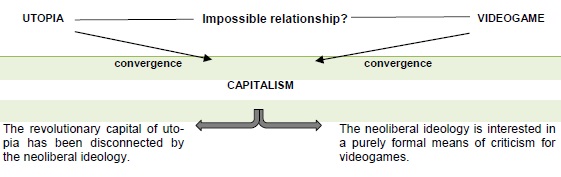

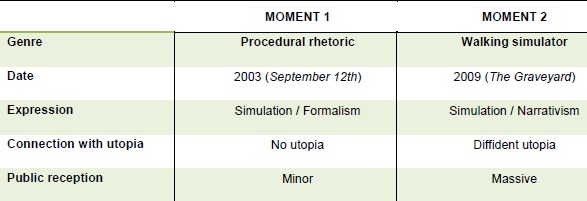

been handed to us (Table 1).

Table 1.

Capitalism, utopia, and videogames.

Ultimately, at present, utopia is

no longer characterised by its capacity to envisage or construct

better worlds. In its new form, the notions of progress and of

improving the conditions of our existence have been supplanted by the

idea of going on a voyage – the farthest flung and costlier the

better. Bauman (2006b) describes an

anecdote that cannot pass without mention: when you enter the word

‘Utopia’ into Google, the first entry that appears is a videogame. Far

from being cause for satisfaction, this fact serves to demonstrate the

widely-held opinion of videogames as a form of ‘holiday retreat’,

refuge, or means of escape, while simultaneously emphasising utopia’s

impotency and, in so doing, relegating it to the mere role of a ludic,

fictional framework.

However, not everything is bleak. The separation between these three

spheres is regarded by other researchers not as a tragedy, but rather

as an integral feature and cause of optimism. McGonigal (2011)

proposes a fluid communication between everyday reality and the

reality established by videogames, to the point of underlining the

influence of the latter on the former. In McGonigal’s perspective, the

key issue of the matter is discovering whether the principles of

compromise and reward, essential in the design of any quality

videogame, can function in a similarly efficient manner in

problem-solving situations in the real world. The answer is strongly

affirmative: “Gamers who have grown up being intensely engaged by

well-designed virtual environments are hungry for better forms of

engagement in their real lives” (2011, 245).

Far from maintaining that there exists a trivial space for culture,

McGonigal states that players are a natural source of participation in

citizen journalism projects, collective intelligence or humanitarian

actions. Proving this phenomenon to be an unstoppable and growing

process, McGonigal speculates that the era of crowdsourcing

videogames will spur the masses to social mobilisation with the aim of

solving real world problems in the same manner as in the ludic context

of virtual worlds (2011, 246).

3.

Case and Methods

In this bleak context, can

videogames bring new life to utopia? This would appear to be a

difficult task. Videogames are a medium erected in the image and

appearance of capitalism: they simulate the remunerative essence of

the system when placing us in the role of an avatar that spends money

or that receives payment for his or her work (Dyer-Witheford

and De Peuter 2012). Moreover, videogames obliterate the idea of

realistic, human worlds that are tied to reality. It is no surprise

that the worlds generated by videogames always appear alien to us,

especially in the most successful games or those received most

favourably by the public. Videogames become locked into the complex

symbolism highlighted by Hauser (1969),

trapped within themselves and revealed to be unabashedly cloaked with

an enticing ‘other-worldly’ nature. Videogames’ strength as a refuge

rests in the fact that they are detached from the everyday, yet this

is also the source of their weakness as an expressive form of social

vocation. The medium’s power to create and change the world was

stripped away at its inception, as it was instilled with the ideology

of its creators, who were essentially engineers and programmers

fascinated by unreal worlds (Anthropy 2012).

Indeed, owing to their mastery of information technology, these

pioneers’ transformative abilities became a simile for the role of

magic in fictional universes, an ostensibly innocuous fact that forced

the medium into exile in the realm of fantasy.

Conversely, the centripetal formalism that is characteristic of the

medium is tied to an ideological evolution where, owing to a sentence

once again handed down by the economic system, our way of relating

ourselves to the world abandoned the domain of ‘knowing’ in favour of

‘processing’. Videogames

synthesise this cultural transformation in the extranoematic effort

required by players during gameplay or in the games’ configuration

based on menus. It is easy to identify any number of human activities

which, in this new ‘processing’ culture, promote the use of

configurative systems based on interfaces akin to those used in

videogames. Such acts of configuration are indispensable in our daily

lives, as much with work as with leisure (Galloway

2006).

Likewise, it is no coincidence that many of the processes and routines

that we carry out in different contexts of our daily lives bear a

resemblance to videogames. As we will see below, the first serious

attempt to connect the medium with the utopian genre rests squarely in

the so-called procedural rhetoric of videogames.

The existing problematic relationship between work and leisure in modern

societies has been thoroughly examined in the scope of game studies. From a strictly ideological perspective, it appears

that the fade of its dividing line is a victory for the current

cultural theory. In our opinion, though, it is misleading to consider

this a triumph. As Eagleton observes (2003, 16),

traditional academism has ignored the daily lives of common people for

centuries. Nowadays, however, we can observe within academia the

synthesis of these formerly irreconcilable instances in a gapless

continuity between intellect, work and daily life. According to market

demands, leisure activities are reintegrated and mixed with labour

activities, thus invalidating the puritan, secular dogma that

establishes that work and play are two different matters. Once again,

the elimination of this boundary has helped the capitalist economic

system and especially the industrial sector of videogames, where most

of the current fans are eager to work voluntarily to fulfil their

entirely emotional and nostalgic wishes. Thus, this new paradox in the

system gives meaning to studies by authors such as Kücklich (2005),

Wark (2006), Lund (2014)

or Bulut (2015).

Kücklich employs the concept of playbour, a blended word composed

of the lexemes ‘play’

and ‘labour’, to

re-evaluate the relationship between play and labour in modding

(computer game modification), where its precariousness “as

a form of unpaid labour is veiled by the perception of modding as a

leisure activity, or simply as an extension of play” (2005, 1). Kücklich tries to clarify the

changing relationship between work and play in the present era, as

well as study its ideological ramifications.

Likewise, we consider the relationship proposed by Wark (2006)

to be substantial; that is, the relationship between the perfection

assigned to videogames and the imperfection of the gamespace, the

latter being a result of the changes that the free market forced into

daily life. The gamespace would be an ideal place for a new figure to

appear: that of the player, transformed into the logical nexus of both

communicational

realities:

Here is the

guiding principle of a future utopia, now long past: “To each according

to his needs; from each according to his abilities.” In gamespace, what

do we have? An atopia, a placeless, senseless realm where quite a

different maxim rules: “From each according to their abilities – to each

a rank and score.” Needs no longer enter into it. Not even desire

matters. Uncritical gamers do not win what they desire; they desire what

they win (2006, 14-15).

The latest research by Lund and Bulut is

focused on the framework established by the writers mentioned earlier,

while simultaneously adding to said framework. Lund argues that an

analysis-based model on the notion of playbour “will help me to

analyse and criticise the contemporary use of the term” (2014,

735), whereas Bulut introduces the fitting concept of

“Degradation of fun” to highlight the way in which “testers’ passion

about video games is contested vis-à-vis the hegemony of precarity in

the profession” (2015, 241).

In spite of the ominous panorama highlighted above, it is

possible to specify at least two moments in the history of videogames

associated with utopia; by describing and analysing both of these

moments, we will be able to conclude whether these associations are

effective. When forming these two categories, specific videogames with

some utopian aspirations but which do not, in themselves, conform to

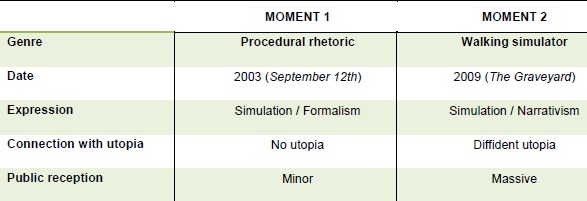

one of the trends have been omitted (Table 2).

Table 2.

Videogame moments associated with the utopian genre.

As noted previously, it was

paradoxically at the very heart of the formalism derived from the

capitalist imprint on the medium that the first attempt to connect

games with aspects of real life emerged. This school of thought, to

which many ‘serious games’ pertain, is called ‘procedural rhetoric’.

It offers an interesting theory of the expressive power of videogames

by using a rhetoric pertaining to the medium itself, erected on the

basic processes derived from its technological nature. In this sense,

we can say that this is a style rather than a generic category, as a

result of which it is susceptible to appearing in a wide range of

games. It was thought that this special capacity of videogames was

sufficient for their achieving a connection with a diverse range of

human issues. Conversely, a decade after the birth of this first

attempt, a new discussion emerged with unexpected momentum concerning

the medium’s capacity to connect with reality. This phenomenon was

associated with a growing number of videogames deemed to be actively

political purely because they drew away from the ludus that is bound to

characterise them in formal, structural, and ludological terms. This

debate involves so-called ‘walking simulators’, a label that refers

both to a generic category and to a style. Understandably, the

propensity of such games to human issues diminishes the significance

of their form – resulting in fewer rules and mechanics – and increases

their narrative value – resulting in a more emotional slant to their

plots. As we will see, these games have sparked a debate concerning

the limits of what does and does not constitute a videogame, and have

led to their association with the moniker ‘social justice warriors’, a

pejorative designation intended to highlight the superficial treatment

of some of the ideas they espouse.

4.

Two Videogame Moments

Associated with Utopia

It

is important that our choice of two particular moments in videogames

associated with utopia be clarified. The first moment, focused solely on

analysing videogames of procedural rhetoric, should be understood within

the context of this article as the epitome of all practices –

ludic, procedural or otherwise, and hermeneutic – that we believe to be unsatisfactory in trying to show and

analyse the videoludic medium as an ideological weapon capable of

revolutionising the strong and reigning neoliberal system. As will be

shown, assuming this impossibility leads to the second moment: the

relationship between walking simulators and a utopian stance that we

have designated as diffident. This is possibly the only true way towards

achieving a utopian construction in videogames.

Despite this

decision, it would be unfair not to acknowledge other writers'

invaluable efforts in recovering, defining and tagging a certain ludic

praxis as an act of dissidence against the Institutional Mode of

Representation and therefore a fitting one to convey the utopia

understood as an alternative to capitalism. Galloway and his concept of

“countergaming” (2006) or Dyer-Witheford and

De Peuter and their notion of “games of multitude” (2010),

are good examples of this. In fact, we cannot ignore the way in which

certain ideas of “games of multitude” are in clear opposition with our

main thesis of a videogame apart from reality. Unfortunately, it is also

important to acknowledge that many of the means proposed by these

authors do not lead to a real electrolysis of the neoliberal system, due

to those means being in the minority and distanced from the mainstream.

Labels such as ‘marginal’ or ‘peripheral’ contribute both to their

definition and to the limitations in their groundbreaking nature. In

capitalist society, using labels to define a phenomenon means that the

system has managed to absorb it. However, the comparisons of some of

these ludic paths with those followed by other means of expression like

cinema or Godard’s “countercinema” (Galloway

2006, 109) are not very useful. We believe that this search for

similarities further highlights the incapability of videogames to change

their destiny. It is important to remember that the Nouvelle

Vague movement established a mode of representation different from

that of the institutions – the

Modern Mode of Representation, with its roots in neorealism in the

Second World War – and its critical project reconstructed the historical sense of

cinema. Are videogames or any other critical project established in

their name prepared to undertake such a task? It is possible that the

only hope lies in the paths known as “counterplay” and “dissonant

development”, outlined by Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter and understood as

“acts of contestation within

and against the ideologies of individual games of Empire” (2010).

The system can only be undone from the inside.

4.1. Are Games with Procedural Rhetoric a Useful Vehicle

for Utopian Ideas?

The key question that predominates

in this type of videoludic discourse is: what problems can videogames

bring to light? One of the genres that is best suited to this social

initiative are so-called ‘newsgames’, which have an informative

purpose tied to current affairs and which originated with the game September 12th (Frasca 2003). Broadly speaking, these games

have resulted in other ludic practices designed to raise public

awareness about topics such as citizens’ rights and responsibilities,

the denunciation of situations of injustice, or educational and

environmental proposals. Many of these ‘serious games’ use procedural

rhetoric, accentuating the principle of simulation specific to

videogames and conferring maximum freedom to the designer to create a

meaning for the game. Nonetheless, this level of control does not

ensure that a correct

meaning about the simulated reality will be generated. As such, our

principal objective is to question the procedural pathway’s capacity,

as a form of game design, to achieve a plausible approximation to

utopia.

Drawing from the definition of the essential properties of digital

artefacts espoused by Murray (1999), Bogost

reveals how videogames function by executing a series of rules (2007).

This

proceduralism is not a practice exclusive to computers; human

societies put a multitude of institutional processes into play. In

consequence, procedural rhetoric is the ideal means of revealing how

any process works by simply adjusting the logic of real systems –

based on processes – to the internal and procedural logic of the

programming languages upon which videogames are based. In consequence,

procedural rhetoric offers a new way of making statements about how

the processes governing human activity function.

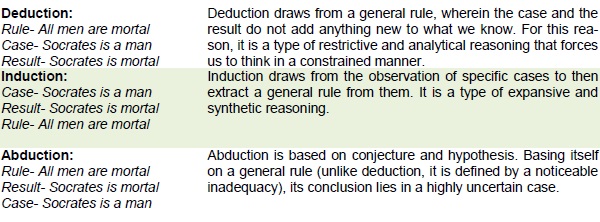

Bogost describes the role of the player in the logic of a procedural

rhetoric videogame by using the simile of a truncated syllogism or

enthymeme. A truncated syllogism is one that avoids one of its

premises purely because its absence does not stop the syllogism from

being understood. As such, the syllogism ‘Socrates is a man, Socrates

is mortal’ elides the main premise or general rule that ‘All men are

mortal’ because this is obvious or, in other words, because it is the

receiver’s responsibility to reach this conclusion. In the case of

videogames, it is the designer’s task to hide the message so that it

can be revealed by the player when playing the game. In both cases,

for the simulation to be produced with guaranteed success, the game

must overcome what Bogost coins “simulation fever”. The culture of

simulation has given rise to certain reactions to simulated works: on

one hand, ‘simulation resignation’ supposes a blind acceptance of any

simulation, even one that is defective; on the other, ‘simulation

denial’ is the rejection of a simulation on the basis of it being a

replica (Turkle 1997). The true value of

simulation emerges when these reactions are overcome: “A simulation is

the gap between the rule-based representation of a source system and a

user’s subjectivity” (Bogost 2007, 107).

In order to reveal some of the contradictions of proceduralism, we will

proceed to analyse a procedural game geared towards understanding

certain social, economic, and political processes that keep countries

in the so-called developing world in a currently irrevocable position

of inferiority. 3rd

World Farmer (Hermund et al. 2008)

is a game that demonstrates the difficulty of generating a stable,

profitable means of agriculture in African countries. What are the

problems this game reveals – and, above all, does it really shed light

on obscure areas whose revelation will allow for change and progress

in these countries? Finally – and an essential question as it is a

regulating idea in proceduralism – which contradictions in the real

system, that is, of African agriculture, does this game expose?

Developed by a group at the IT-University of Copenhagen, the game begins

with the slogan ‘a simulation to make you think’, and its main premise

is managing a farm run by an African family. The difficulties the

player is faced with are based on chance and on the political,

economic, social, and natural circumstances that shape the destiny of

the family’s crops. As such, the success of a crop that is essential

to the family’s survival not only depends on the appropriate or

inadequate distribution of resources – different crops, farm animals,

farming tools – but is also affected by numerous variables of a

negative complexion, such as wars, political changes, and natural

disasters, that almost always conclude in the death of one of the

family members or, worse still, its entire disappearance. The game is

organised into turns that simulate the duration of a crop, in which

the decisions made by the player – lawful or illicit, good or bad –

are seen to be disrupted by these uncontrollable negative variables.

Other decisions, such as sending the children to learn at school,

simultaneously entail a considerable financial toll and reduce the

family unit’s work capacity, accentuating how fragile the family is

and effectively condemning it to extinction.

So, does 3rd World

Farmer really make us think? Let us consider this point in

greater detail. Firstly, and following the proceduralist maxim of the

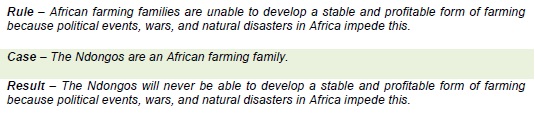

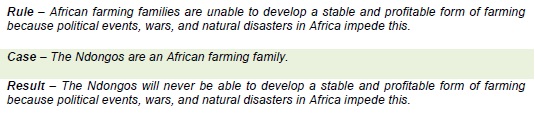

enthymeme, the syllogism that allows for the videogame to be

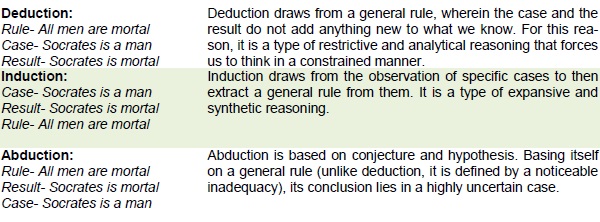

understood is portrayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Syllogism in 3rd World Farmer.

The syllogism appears to be

truncated in the game owing to the absence of its general rule: it is

in the act of playing that the player is able to understand this rule,

that is, the gloomy revelation that, in Africa, it is impossible to

generate a stable economic system based on agriculture – a fact that

would surely already be common knowledge for a player who is

interested in the mass media’s political agenda in the ‘First World’.

The omitted general rule is the effective presence of a dominant

ideology that has imposed an inexorable sentence on these countries,

an ironclad law that stops the player from considering other

possibilities that are not contemplated by this law.

What we learn and think about as players of a procedural rhetoric

videogame such as 3rd

World Farmer is not distinct from what we already know as

members of a specific ideology that looks on Africa with a certain

degree of scepticism. As such, the game itself stigmatises an entire

geographical zone that is as large as its problems are varied,

adopting the historical and Eurocentric judgement of African unity

and, if this were not enough, equating the label ‘Third World’ with

the realities of the African continent. To consider its nature in

greater detail, perhaps we can assume that all the problems in the

underdeveloped world relate solely to agriculture and that they are

all represented in this game? The response can only be in the

negative, and the subjective distance between the simulation and the

simulated reality is too vast for us to suspend our disbelief.

Conversely, the type of thinking generated in the player during the

act of playing moves within the reassuring realm of deduction (Vargas-Iglesias

2018), where the framework erected by this general, described

rule impedes the emergence of any form of creative or conjectural

thinking that may allow for the simulated reality to be modified. We

consider ourselves to be incapable – as is also the case for our

family in the game – of contemplating other possibilities that could

help us find solutions to the problems that are identified. What,

then, is the purpose of a game that reaffirms and highlights an

ideology without proposing any kind of investigation that could

alleviate, modify, or transform the situation in question? The

videogame is revealed to be both futile and dependent on a complex

real experience that acts as a burden from which it cannot extricate

itself: it is in this same burden that its meaning lies. The

relationship that the videogame upholds with its simulated reality is

that of an incomplete object owing its comprehension to a reality

structured around hundreds of variables that it cannot entirely

simulate and, worse still, that it is unable to modify. Both

simulation and simulated reality share the same general rule that

precludes individuals and governments from finding creative solutions

to the problems faced by these countries. Indeed, it is this shared

factor that plunges us into the true dilemma of procedural rhetoric

games: their incapacity to generate an appropriate poetics of meaning

and significance.

4.1.1. Results and Conclusions

Our critique of proceduralism is

comprised of two fundamental ideas, converging in a crisis concerning

this pathway’s ability to act as a vehicle for utopia with guaranteed

success. In the first instance, what is the purpose of a game whose

meaning effectively rests in the process being simulated, rather than

in the simulation itself? Effectively, the simulation of a real

process via the procedural rhetoric of a game can be perceived to be

an intertextual correspondence where, on most occasions, the

significance of the game exists outside itself, that is, in a specific

ideology that keeps the game in a relationship of servitude.

Consequently, in the second instance, procedural games do not transmit

new or conjectural ideas, but are instead blinded by a specific

ideological perspective that ultimately comes to define them.

Therefore, if procedural rhetoric always acts at the behest of an

ideology, it follows that it rarely serves to generate new solutions

to the issues that are presented. This is the case because, in terms

of their constitution, these games are based on deductive cognitive

processes that refute the abductive nature of videogames (Navarrete-Cardero

et

al. 2014).

The heuristic incapacity of procedural games is a consequence of their

strictly formalist structure; as such, they must be judged according

to structuralist criteria. Genette (1997)

alludes to the classic distinction introduced by Michael Riffaterre in

the relationships that texts uphold with meaning and significance. To

summarise, Riffaterre shows how all texts have their own meaning; that

is, they have a specific interpretation, but they do not control its

significance. In order to access a poetics of significance, works must

transcend their limits and reveal the connections they maintain with

other texts – or other realities – in textual or relative terms; it is

only in this way that we can know the genre to which a work pertains,

the genealogy of its structure, or why its protagonists are

constituted in a certain way. It is, of course, here where the

procedural proposal fails to produce serious videogames associated

with utopia. Let us imagine the following cases:

A. A procedural videogame is well

designed and the player is unaware of the simulated reality. In

this case, the player can access the realm of meaning, that is, a

specific interpretation of the game, but not the game’s significance.

The pretence that a player can access the realm of significance – that

is, that they can grasp the simulated reality because of the game – is

to think of learning as a simple process of content absorption:

“Picture that sequence from The Matrix where Neo has new skills downloaded directly into his

head and can use them instantly” (Jenkins

et al. 2009, 448). In our opinion, it is only in a serious game

that seeks to inform the player about something they are unaware of –

an omitted general rule that they are required to deduce – that a

satisfactory simulated experience is plausible. However, even in this

case, though the game would succeed in achieving a certain degree of

utility, we must recognise that it would only do so because of the

player’s lack of knowledge about the simulated reality. As such, how

can the player calibrate the utility of an experience that is forged in absentia of their

knowledge of said reality? Are they expected to blindly trust a

message accessed by deductive means that reveals the dominant

ideology?

B. A procedural videogame is

poorly designed and the player is aware of the simulated reality. In

this case, owing to the incorrect implementation of the mechanics or

another kind of imbalance, the game generates a meaning that does not

reside in the game itself, but which surfaces solely because of the

player’s knowledge of the simulated reality. The impossible suspension

of disbelief, that is, the appearance of simulation denial, annuls any

contract of significance between game and simulated reality. Instead,

such a situation results in a pointless game based on a deductive type

of thinking, where only knowledge of the general rule – in the form of

an enthymeme of the game – justifies the game’s meaning, underlying

its scant heuristic value and negating any expansive type of knowledge

concerning the simulated reality.

C. A procedural videogame is well

designed and the player is aware of the simulated reality. In

this case, the videogame generates its own meaning and accesses the

realm of significance, connecting with the simulated reality in a

pertinent manner via simulation resignation. This would be an ideal

situation were it not for its deductive structure, which, as in the

previous case, will never give rise to a new perspective on that

reality. As such, the heuristic value of this pathway is trivial and

only serves to emphasise a predetermined ideological framework.

Moreover, if we consider the affinity between the ideology of the

player and the ideology of the game, new dissonances are created both

in the realm of meaning and in the realm of significance. For example,

in this case’s ideal situation, can we speak of the emergence of

significance if the player’s ideology does not coincide with the

ideology of the game? Would all the connections geared towards the

constitution of significance not short-circuit in the case of an

ideological clash? In such a situation, would the player not reject

the simulation owing to subjective impertinence, resulting in a

situation similar to the one we are exposed to by a poorly designed

game? And even if we were to imagine a situation where there was an

ideological meeting of minds, what purpose would a game celebrating a

specific ideology serve if this ideology were not discussed or

interrogated?

D. A procedural videogame is

poorly designed and the player is not aware of the simulated

reality. In this case, the videogame does not generate a

meaning, nor does it access the realm of significance.

4.2. A Fluid Game: Are Walking Simulators a Useful

Vehicle for Utopian Ideas?

The term

‘walking simulator’ has its origins in the early 2000s, with strictly

negative connotations. However, these connotations eventually

disappeared, thus demonstrating the creative possibilities of this new

ludic genre. Although this positive reframing of its meaning in gamer

culture still has no influence in academia, it is possible to find it

in specialised journalistic criticism, more focused on detecting

fluctuations in the player's taste and choice (Clark

2017; Muriel 2017; Ortega

2017). Evidence of this conceptual revitalisation can be found

on platforms like Steam, GamersGate or Itch.io, where games bearing

this tag can be searched without any negative connotation attached to

them.

The origin of

this genre is possibly found in the 2003 proposal of artist and author

Mary Flanagan, Domestic. “[Domestic]

uses a software engine normally used to generate violent first-shooter

video games in order to reconstruct a remembered childhood space where

a dramatic event has taken place: a house fire” (Flanagan

2003). In recent years, examples of this type of games have

increased exponentially, not only as a commercial strategy to reach a

broader and more casual audience, but also as a relatively easy and

inexpensive means for independent studios to access game development.

In the field of specialised criticism, walking simulators have

revitalised the old debate, perhaps also noticeable in this article,

between ludologists and narratologists. Bogost sets an example of this

trend when commenting on Dear

Esther (The Chinese Room, 2008), Gone

Home (Fullbright, 2013) and, especially, What

Remains of Edith Finch (Giant Sparrow, 2017):

What

are games good for, then? Players and creators have been mistaken in

merely hoping that they might someday share the stage with books,

films, and television, let alone to unseat them. To use games to tell

stories is a fine goal, I suppose, but it’s also an unambitious one.

Games are not a new, interactive medium for stories. Instead, games

are the aesthetic form of everyday objects. Of ordinary life. Take a

ball and a field: you get soccer. Take property-based wealth and the

Depression: you get Monopoly. Take patterns of four contiguous squares

and gravity: you get Tetris. Take ray tracing and reverse it to track

projectiles: you get Doom. Games show players the unseen uses of

ordinary materials (Bogost 2017).

Nevertheless,

in our opinion, Bogost forgets the fact that there are three different

and concomitant dispositions in What

Remains of Edith Finch, though not exclusive to the genre and

shared across many other games: the hunter’s gene, the scopic drive of

the flâneur, and the investigator’s thirst for knowledge. It

can be argued that, aside from the clear relationship that these

activities have with the ludic sphere, these three dispositions have

the same principle: searching for a way to control the surrounding

reality, an attitude that can be inferred from the nature of fluid

games and their relation with the utopic genre of walking simulators.

The player has inherited the spectator’s wish of seeing it all, now

enhanced by their ability to eavesdrop, examine and touch many places

of the setting. The key difference, and not a trivial one by any

means, between the Baudelairean flânerie and the motion of the

wandering player in walking simulators is manifested in the role of

presence in capitalist modernity, as pointed out by Benjamin. Thus, to

Baudelaire, Poe or Benjamin years later, the wanderer is a man of the

crowd (Benjamin 1972). On the other hand,

the man who wanders in walking simulators is a solitary man, a

searcher of signals and traces. Our interest in this genre lies in

this search.

As stated in Section 2 of this article, the current dominant ideology,

based on an economic system that is immune to any form of attack,

renders all actions destined to modify specific realities ineffective.

Videogames based on procedural rhetoric are destined to fail owing to

their lack of practical utility. If a lesson can be learned from the

inefficacy of procedural games, it is fact of the impassable divide

between the inflexible processes of our society and any agenda or

stratagem geared towards modifying their status. The present general

order and its underlying processes do not allow for options: there is

no clear route to utopia. As Bauman notes: “[…] it is far from clear

what such options could be, and even less clear how an ostensibly

viable option could be made real in the unlikely case of social life

being able to conceive it and gestate” (2006a,

5). The systemic critique of contradictions in the processes of

capitalist society is shown to be futile because the power to modify

them has been liquidated by the new, inflexible, and immutable order

of neoliberalism. A videogame geared towards exposing the

contradictions of certain processes in our reality purely to show them

to us – given that they possess no capacity to eradicate them – thus

becomes the most accurate symbol for the new human condition.

What is this new human condition? Using Bauman’s terminology, procedural

rhetoric games have been geared towards the impossible objective of

modifying the most solid order that has ever existed, one established

by an economic system that has thrown off all the remnant shackles of

previous orders by melting its ‘solids’. All the political or moral

powers capable of combating or reforming this new order have been

destroyed or rendered too weak for the task (2006a,

4). The present system’s solidity cannot be modified by a

political agenda because this same system has dissolved the

previously-existing nexus between individual choices and collective

projects. Indeed, due to deregulation, liberalisation, market

flexibility, and the fluidity of the labour and real estate markets,

the system’s strength is rooted in a total freedom of human agents,

facilitating an absence of cooperation between these agents – that is,

us – and the system. Instead of bending to us, this system appears to

elude us (2006a, 5). In consequence, for

the first time since the dawn of modernity, the construction of rules,

customs, or norms for the success or failure of our existence is not

incumbent on the system: it is a responsibility that has expressly

fallen onto the shoulders of every individual. This new condition of

man, defined as ‘liquid modernity’, is characterised by its

malleability and the notable effort exerted by individuals to endow it

with an almost-always transient form of stability (2006a,

8).

In this new, liquid dimension of modernity, people have abandoned their

dream of modifying systemic processes upon which they exert no

influence. They conform and are simultaneously forced to turn within

themselves, with an urge to transform the search for stability into

their sole life’s project. With the possibilities for building a new,

better order extinguished, a forced internalisation of utopia is

produced, motivated solely by a desire to generate a favourable

personal world in an unfavourable context. This internal search has

its correlate in a type of videogame that is less ambitious than

procedural games, dedicated to narrating – yes, narrating

– our small place in the world. The current incarnation of this type

of game is the walking simulator, a fluid videoludic discourse that

renounces the utopia of impossible global change to instead focus on

the infinitely small aspects of our daily lives, identifying the

emotions experienced within them, highlighting their successes and

failures, and intending to supply our lives with the stability that we

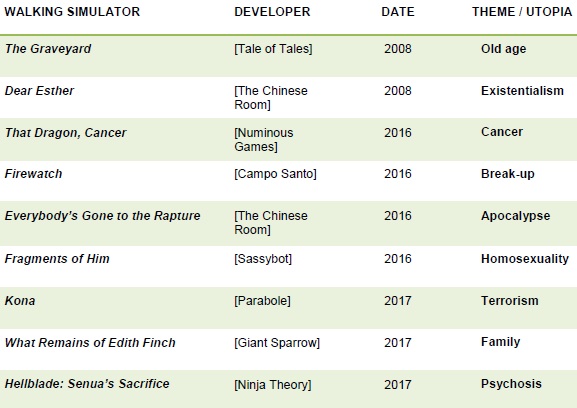

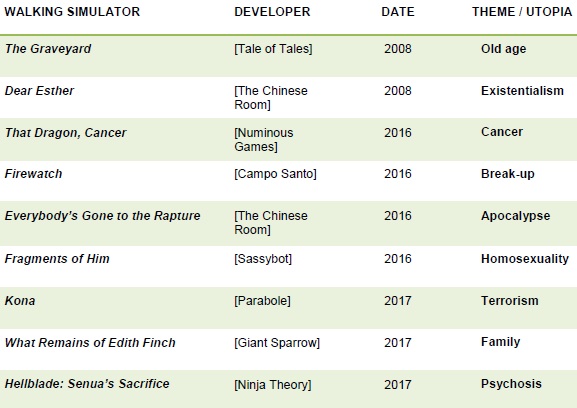

crave (Table 4).

Table 4. Fluid

videogames: walking simulators and utopia.

It is no coincidence that these

games have emerged within a community of independent developers, just

as it is that games in this pathway construct – in a purely humanist

sense – a space dedicated to reflection. We classify this utopia as

‘diffident’, that is, a utopia that is timid, fearful, and

fainthearted if we compare it with genuine utopian vehemence. Perhaps

it is this utopian diffidence, present in many walking simulators,

that has led many videogame critics to associate these games

negatively with the label ‘social justice warrior’:

A pejorative

term for an individual who repeatedly and vehemently engages in

arguments on social justice on the Internet, often in a shallow or not

well-thought-out way, for the purpose of raising their own personal

reputation (Urban

Dictionary 2017).

It is, of course, true that some of

these videogames use sensitive social themes as a mere ludonarrative

context, rarely proposing solutions to them or reflecting on them.

Such games use these topics as a superficial plot device without

answering the questions that they inevitably elicit in the player.

Nonetheless, we believe that to extrapolate this behaviour to all

fluid videogames is an act that is as small-minded as the excessive

and unjustified praise that is sometimes lavished upon them. This

dualist critical perspective of walking simulators, fluctuating

between panning and flattery, has stretched the debate to other

elements such as their artistic capacity, their ludic nature, or their

social commitment:

These types

of games are beloved by Feminist Frequency types who hail them

as brilliant alternatives to the “male power fantasy” inherent in most

big budget violent games. Many jaded, liberal, gen-X reviewers inflate

the scores of these titles, saying these are finally games made for

“adults,” and chiding the wider industry for its perceived immaturity (Hicks 2016)

[…]

story-focused games [are] more like films than games, goes

the usual critique, and games are supposed to be games. Worse, these

games often tackle themes like race, class, identity, and so forth,

inevitably offering up some sort of progressive message — they’re

political, which is just about the worst and most annoying thing a video

game can be (Singal 2016)

Yet, paradoxically, these games

prove to be extremely enriching in a personal sense when they root us

in existential universes, put us face-to-face with cancer, or give us

a closer insight into psychosis. These games humanise the medium of

videogames, tie them to reality, and invite us to empathise with

situations that we may not have experienced. Despite this enormous

power, they are accused of not being authentic games due to the lack

of actions available during gameplay. Indeed, the actions in a walking

simulator do not occur ‘from the top down’, which is the usual

framework for actions that can be performed in a traditional

videogame; instead, this type of game attempts to simulate actions

‘from the bottom up’, a decision that distances it from the pure ludus

and from a strictly ergodic goal and draws it closer to abstract

objectives that are often purely emotional. Is this relocation of

actions a sufficient reason to expel walking simulators from our

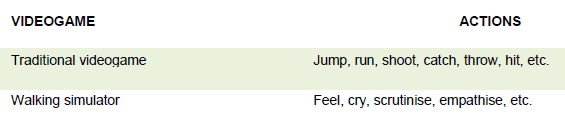

videoludic paradise? (Table 5).

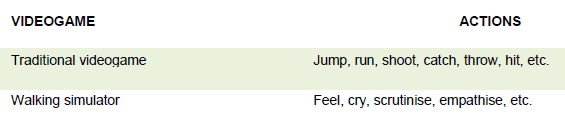

Table 5.

Actions in traditional videogames and fluid videogames.

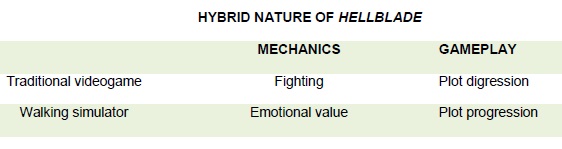

The characteristics of fluid

videogames can be seen in any walking simulator. In order to

demonstrate some of their qualities, we will focus on a game from the

latest generation that has an ambiguous, hybrid nature. Indeed, Hellblade:

Senua’s

Sacrifice (Ninja Theory 2017)

intersperses a realistic and human complexion with the façade, and

certain ludic hallmarks, of a triple-A title. This game boasts an

enthralling plot concerning the protagonist’s psychosis, and a bipolar

form of gameplay that oscillates between a prototypical walking

simulator and a ‘hack-and-slash’. The latter aspect reveals a hidden

tension in the player derived from their preference either for Senua’s

story, concerning the psychotic process and the game’s walking

simulator nature, or for the moments when the protagonist has to

fight, a remnant of its hack-and-slash origins that entails a break

from the narrative discourse by obliging us to take up the sword and

act in classic ludic fashion. This strange case of ‘Dr. Walking

Simulator’ and ‘Mr. Hack-and-slash’ can be summarised as shown in

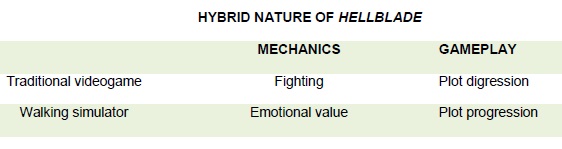

Table 6.

Table 6.

Fusion of fluid videogame and triple-A title.

The player’s ludic reality is

nothing other than Senua’s psychotic crisis, produced by her shock at

the death of her loved one. Through her heroic quest, transformed into

our ludic experience, the player is able to discover the possible

genesis of Senua’s psychosis, her relationship with her evil father,

and the significance of the absence of her mother. Perhaps our

adventure is no more than a hallucination produced by Senua’s

tormented mind, or maybe the struggle against darkness takes place

only in her psyche.

4.2.1. Results and Conclusions

Does Hellblade

break any new ground with regard to psychosis? In the game’s

narrative, there is evidence that rigorous research about the disorder

was undertaken, a fact that is subsequently emphasised in the

execution of its visual, acoustic, and ludic components. As such, the

voices heard by Senua or the puzzles resolved by the player during the

game are closely tied to the symptoms, hallucinations, and delirium

caused by this illness. It is clear that the way psychosis is dealt

with in the game draws on the advice of health specialists and people

experienced in working with individuals suffering from the disorder,

as Ninja Theory has itself noted in a self-produced documentary. As a

result, the game’s main virtue is the discovery of psychosis by those

who know nothing about it and who do not have to live with its harsh

realities. Senua’s ludic incursion into an increasingly dark world is

the figurative antithesis of the path to knowledge pursued by the

player vis-à-vis this mental illness. Is this fact sufficient for

recognising this game’s social validity? Does the game help to

construct a better world in the terms defined earlier in this article?

Does it merely use psychosis as a means of constructing a lifelike

character, or are there philanthropic interests at play? In our

opinion, what is most important is not the content of these queries,

but instead the very possibility of articulating them in a mass-market

videogame.

5.

Discussion and General

Conclusions

This

article aspires to provide answers to two questions: the first asks if

it is possible to identify a link between utopia and videogames; the

second focuses on the possibility of transcending the formalism of

ludology and thus the cybernetic groundwork found in the neoliberal

paradigm of control.

The

identification of two historically significative forms in which both

concepts have built their relationship (rhetorical procedure and walking

simulators) has been useful to answer affirmatively to the first

question, although the appeal of the first case to the enthymeme and

thus to narrow and preconceived discourse differs from the humanist

performance of the second case. Regarding the second question, as a

consequence of an analysis of the said difference, a utopian potency

which transcends the formal limitations of proceduralism has been found

in walking simulators. This videoludic formula inaugurates what we term

a ‘diffident utopia’, consisting of an intimist version of the old

utopia in that it is based on microprocessual dynamics that, by means of

being based on a certain ethics of care, moderate the medium by making

it stray away from ‘strong’ structural logics. This helps this formula

to become the most solid candidate to the expression of utopia according

to the options suggested by the cybertextual logics of videogames.

These

conclusions suggest certain questions. On one hand, the exclusive association of two moments in

videogames with utopia –

procedural

rhetoric

and walking simulators –

at

the

expense of other analytical possibilities is both a risk that

researchers are to take and a way of saving effort. Clearly, this

decision does not exclude other possibilities, as new relations

between the utopic genre and other videoludic genres and styles can be

found. As such, we assume the successes of this decision, but we also

assume responsibility for its shortcomings. We have considered that

these two methods are the most logical ones with which to undertake an

initial approach to the videogame’s relationship to utopia, and we are

also willing to admit that they might be guided by a criterion of

obviousness: the high amount of political content of most of the

procedural games and the deep influence of moral compromise in many

walking simulators made us choose this path, clear and expeditious to

us. Likewise, we do not believe that it is necessary for there to be a

definite utopic intentionality in the creation of these games. As

suggested by Deleuze (1968, 125), Eco (1979),

and Foucault (1969), the work, once

abandoned by its creator, stands on its own, and thus the researcher

has the responsibility to determine its social function and grant it

critical value via the rules of academic debate.

From a quantitative perspective, the

affirmations in this article related to procedural rhetoric games are

based on a case study of very limited scope. This fact, otherwise

conscious, lies in the certainty that both the structure of procedural

rhetoric games and their ideological nexus with simulated reality

remain intact in any game designed according to its principles.

Although they are not directly referenced in this article, many other

games were taken into account when exploring the shortcomings of this

ludic typology in relation to its capability of creating plausible

solutions to real problems that can connect it with the creation of

utopias. For instance, the games by La Molleindustria – from McDonald’s Video Game (2006) to To

Build

A Better Mousetrap (2014) and Nova

Alea (2016) – cannot escape the formalism and the logic of their

structure per se, since

they are based on an enthymemic scheme. Therein lies the greatness and

the hardship of these games: they can denounce dissonant processes in

our society, but they must always do it under a specific ideology they

serve, whether akin or opposed to ours, that is eventually established

as a premise or main rule of its syllogistic base.

Table 7.

Methods of human-scientific reasoning.

This

happens because procedural games have excluded every definition of the

word “game” that relates to leisure, since they must move in a

deductive frame. It is important to remember that the greatness of the

medium lies in its abductive power (Navarrete-Cardero

et al. 2014). As critic Stanley Fish states, no theory (rule or

norm) in post-modern society can change our personal beliefs (Norris

1998, 108). This fact greatly hampers the purported rhetoric

effectiveness of these games (Table 7). In our perspective, procedural

games could never serve as a means for the utopia, due to their

deductive frame preventing the establishment of a rule, i.e. an

ideology, from which all other plausible premises emanate in a

restrictive and analytical manner. In these games, there is no room

for conjecture and hypotheses, i.e. fundamental drivers of change and

transformation of any given reality into a distinct one. Without

abduction, there can be no change; without change, there can be no

utopia.

It is paradoxical that a genre like that of

walking simulators, whose origins were fraught with infamy, could have

a specific and special seed of utopia. On the other hand, it is

disheartening that the nature of this possibility of change can only

be conceived in internal and personal terms, in a very individual

manner. Certainly, as we have ascertained, the reluctance of the

neoliberal society of today to accept any modifications or

alternatives (Jameson 2005; Fisher

2009) has eliminated the utopic action in our lives. A single

look out of the window is enough to prove that this statement is

certain and substantial. As we have seen, the systemic criticism of

the contradictions in the processes of our society is useless since

the power to change them has been taken away from us by the new,

inflexible and immutable order of the present neoliberalism. A

videogame – in the

case of those based on procedural rhetoric – attempting to demonstrate the contradictions of certain processes of our

reality just to show them becomes the most accurate representation of

the new human condition, as it lacks the ability to eliminate said

contradictions. Everybody seems to have abandoned their dream of

changing systemic processes that they bear no influence on. People

fall into conformism and are forced to look inside themselves, urged

to consider the search for a certain stability to be their only

purpose in life. Without any possibility of creating a new, better

order, a forceful interiorisation of the utopia is produced and this

is eventually identified with the sole wish to create a personal,

favourable world in an unfavourable context. In our opinion, walking

simulators are the correlate of this existential phenomenon and its

videoludic expression.

In conclusion, it is important to ratify one of the fundamental ideas of

this research: the current inability of the videoludic medium to alter

the environing reality underlines the separation, in modern societies,

of the spheres – cultural, economic, political – advocated by Marcuse

(1968) or, more recently, by Dean (2005)

through his concept of “communicative capitalism”. This problem is not

exclusive to the videoludic medium: cinema and novels are, to this

date, also unable to do so. The difference, as interpreted from the

statements by Bogost (2017), lies in the

unconscious existence of a global drive to distance videogames from

any utopian attempt, i.e. its narrative aspect – the data suggests

that this goal can only be pursued via narration – to reaffirm it in

its nature as an entertainment device and artefact. In our view, the

unique situation of videogames is not coincidental, but rather a

condition induced by systemic determinations that can be considered a

triumph of neoliberalism.

6. References

Aarseth,

Espen.

1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature.

Baltimore: JHU Press.

Anthropy,

Anna.

2012. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals,

Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Drop-outs, Queers, Housewives, and

People Like You are Taking Back an Art Form. New York: Seven

Stories Press.

Balasopoulos, Antonis.

2008. Utopiae Insulae Figura:

Utopian Insularity and the Politics of Form. Transtext(es)

Transcultures,

Journal of Global Cultural Studies. doi:10.4000/transtexts.213

Bauman,

Zygmunt.

2006a. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bauman,

Zygmunt.

2006b. Living in Utopia. In Soundings 33:

1-13.

Bell,

Daniel.

1996. The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. New

York: Basic Books.

Benjamin,

Walter. 1972. Iluminaciones

II. Baudelaire. Un poeta en el esplendor del capitalismo.

Madrid: Taurus.

Bogost,

Ian. 2007. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of

Videogames. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Bogost,

Ian. 2017. Video Games Are Better Without Stories. Film,

television, and literature all tell them better. So why are games

still obsessed with narrative? The

Atlantic. Accessed May 13, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/04/video-games-stories/524148/

Boltanski, Luc and Eve Chiapello. 2002. The New Spirit of

Capitalism. London: Verso.

Bulut,

Ergin.

2015. Playboring in the tester pit: The convergence of precarity and

the degradation of fun in video game testing. Television

& New Media 16

(3): 240-258.

Bulut, Ergin,

Robert Mejia and Cameron McCarthy. 2014.

Governance through Philitainment: Playing the

Benevolent Subject. Communication

and Critical/Cultural Studies 11

(4): .

Clark, Nicole. 2017. A Brief

History of the “Walking Simulator”, Gaming’s Most Detested Genre. Salon. Accessed May 13, 2018. https://www.salon.com/2017/11/11/a-brief-history-of-the-walking-simulator-gamings-most-detested-genre/

Costikyan,

Greg.

2013. Uncertainty in

Games. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dean,

Jodi. 2005. Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the

Foreclosure of Politics. Cultural Politics 1

(1): 51-74.

De

Koven,

Barnard. 2013. The

Well-Played Game. A Player’s Philosophy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Deleuze,

Gilles.

1968. Différence et

répétition. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Deleuze,

Gilles

and Félix Guattari. 1972. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalisme et

schizophrénie. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Dyer-Witheford, Nick and Greig de Peuter. 2010. Games of Multitude. The

Fibreculture Journal 16.

Dyer-Witheford, Nick and Greig de Peuter.

2012. Imperio@play: videojuegos y capitalismo global. In Extra

Life: 10

videojuegos que han revolucionado la cultura contemporánea,

edited by Errata Naturae, 237-268. Madrid: Errata Naturae.

Eagleton, Terry. 2003. After

Theory. New York: Basic Books.

Eco,

Umberto.

1979. Lector in fabula. La

cooperazione interpretative nei testi narrative. Milan:

Bompiani.