Reflections on Michael Hardt and Antonio

Negri's Book “Assembly”

Christian

Fuchs

University

of Westminster, London, UK, christian.fuchs@uti.at, @fuchschristian, http://fuchs.uti.at

Abstract: This contribution

presents reflections on Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s book “Assembly”

(2017, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0190677961).

Keywords: assembly, Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri, multitude, common,

entrepreneurship of the multitude, the new Prince, digital capitalism, digital

assemblage, neoliberalism, finance

1. Introduction

Hardt and

Negri's Assembly is a critical, broad, all-encompassing analysis of

contemporary society. It is a major work that turns the trilogy of Empire

(2000), Multitude (2004) and Commonwealth (2009) into a

tetralogy. These four works are organised around a core of concepts (empire,

the multitude, the commons, immaterial labour) that has developed over a time of

seventeen years in response to capitalism's struggles, contradictions, and

crises. The book intervenes into the most recent developments of society and

social movements. It asks: “Why have the movements, which address the needs and

desires of so many, not been able to achieve lasting change and create a new,

more democratic and just society?”. For providing an answer, Hardt and Negri

analyse recent changes of politics and the economy.

Assembly focuses on a diversity of interconnected

topics such as changes of capitalism, the social production of the commons,

digital assemblages, neoliberalism, financialisation, neoliberalism, right-wing

extremism, protest and political change, political strategies and tactics,

social movements and political parties, the entrepreneurship of the multitude,

the appropriation of fixed capital, prefigurative politics, taking power

differently, antagonistic reformism, political realism, or the new Prince. The

book offers something interesting for lots of different critical groups and

individuals, who care about understanding society and changing it toward the

better.

The book’s main body consists of 295 pages and a ten-page preface

organised in sixteen chapters and four parts. Parts I and IV (“The Leadership

Problem”, “The New Prince”) focus on issues of political strategy and tactics,

whereas parts II and III (“Social Production”, “Financial Command and

Neoliberal Governance”) analyse capitalism’s transformations. The theoretical

approach taken is a critical political economy influenced by Karl Marx, Michel

Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Machiavelli and Spinoza.

2. Capitalism

Hardt and

Negri analyse capitalism as a contradictory open totality that in its

development has become ever more social and co-operative, but is subject to the

dominant class’ and political elites’ control. A dialectic of crises and

struggles drives the development of these contradictions.

The social production of the commons that are exploited by capital is a

key feature of the contemporary economy and society. “Today production is

increasingly social in a double sense: on one hand, people produce ever more

socially, in networks of cooperation and interaction; and, on the other, the

result of production is not just commodities but social relations and

ultimately society itself” (xv, see also 78).

The common consists for Hardt and Negri of two main forms, the natural

and the social commons (166), that are divided into five types: the earth and

its ecosystems; the “immaterial” common of ideas, codes, images and cultural

products; “material” goods produced by co-operative work; metropolitan and

rural spaces that are realms of communication, cultural interaction and

co-operation; and social institutions and services that organise housing,

welfare, health, and education (166). Contemporary capitalism’s class structure

is for Hardt and Negri based on the extraction of the commons, which includes

the extraction of natural resources; data mining/data extraction; the

extraction of the social from the urban spaces on real estate markets; and

finance as extractive industry (166-171).

Hardt and Negri analyse capitalism as having developed in three phases:

the phase of primitive accumulation, the phase of manufacture and large-scale

industry, and the phase of social production. In chapter 11, they provide a

typology of ten features of these three phases. In this analysis, a difference

between Hardt/Negri’s and David Harvey’s approach becomes evident: Whereas

Harvey characterises capitalism’s imperialistic and exploitative nature based

on Rosa Luxemburg as ongoing primitive accumulation, primitive accumulation is

for Hardt and Negri a stage of capitalist development. They prefer Marx’s

notions of formal and real subsumption for characterising capitalism’s

processes of exploitation and commodification. In an interlude, Hardt and Negri

explicitly discuss this difference of their approach to the one by David Harvey

(178-182).

David

Harvey uses the notions of formal/real subsumption and primitive accumulation

in a converse manner to Hardt/Negri: Whereas primitive accumulation is in his

theory an ongoing process of accumulation by dispossession, formal and real

subsumption characterise two stages in the development of capitalism, one

dominated by absolute surplus-value production, the other by relative

surplus-value production. Harvey (2017, 117) in his most

recent book Marx, Capital and the Madness of Economic Reason says that

Marx describes a “move from a formal (coordinations through market mechanisms)

to a real (under the direct supervision of capital) subsumption of labour under

capital”. “All the features of primitive accumulation that Marx mentions have

remained powerfully present within capitalism’s historical geography up until

now” (Harvey 2003, 145).

Whereas there are commonalities of Harvey and Hardt/Negri’s analysis of

the commons and urban space (see Harvey, Hardt and Negri 2009),

it is evident that there are also differences. There is certainly not one

correct or valid interpretation of Marx. The decisive circumstance is that Marx

200 years after his birth remains the key influence for understanding

capitalism critically. Both Harvey’s and Hardt/Negri’s works are updates of

Marx’s theory under the conditions of 21st century capitalism. As

long as capitalism exists, people will continue to read Marx in order to find

inspiration for how to organise social struggles and will produce new

interpretations of Marx. The deep economic crisis of capitalism that has

been accompanied by political crises has after decades of postmodernist and

neoliberal repression increased the interest in Marx’s works.

Another interesting question that Hardt and Negri’s Assembly

poses implicitly is: In what type of capitalism do we live? What dimension of

capitalism is dominant? This question has recently also been asked in a debate

between Nancy Fraser and Luc Boltanski/Arnaud Esquerre (see Boltanski

and Esquerre 2016, 2017; Fraser 2017).

Boltanski and Esquerre suggest the emergence of a new form of cultural

capitalism that is based on enrichment from collectibles, luxury goods, brands,

arts, heritage, culture, fashion, trends, etc. They speak of the emergence of

an integrated capitalism that is based on four forms of valorisation that are

based on standardised mass production, the collection form, the trend form and

the asset form. Boltanski and Esquerre’s approach shows certain parallels to

Hardt and Negri’s in that both stress that the boundaries of the company and

society and between leisure and labour have in the production of value become blurred:

“Work is no longer concentrated in factories and identified as a factor of

production; instead, the workforce is widely dispersed, divided between public

and private domains, between permanent employees and the informal precariat. It

is also spread across a much wider range of activities, many of which are not

even identified as ‘work’, but rather presented as an expression of ‘desire’ or

‘passion’, even by those who engage in them, often at heavy cost” (Boltanski

and Esquerre 2017, 54).

“Today the divisions of the working

day are breaking down as work time and life time are increasingly mixed and we

are called on to be productive throughout all times of life. With your

smartphone in hand, you are never really away from work or off the clock, and

for a growing number of people, constant access not only confuses the

boundaries between work and leisure but also eats into the night and sleep. At

all hours you can check your e-mail or shop for shoes, read news updates or

visit porn sites. The capture of value tends to extend to envelop all the time

of life. We produce and consume in a global system that never sleeps” (Hardt

and Negri 2017, 185).

Nancy

Fraser (2017) argues that Boltanski and Esquerre overestimate cultural

capitalism and underestimate finance. In her view, finance capitalism is the

dominant form and dimension of capitalism today: “I worry, […] that

Boltanski and Esquerre overestimate enrichment’s importance. Perhaps the latter

is best understood as an exotic corner of present-day capitalism […] My own

candidate for contemporary capitalism’s dominant sector is finance. Despite its

enormous weight and political consequence, finance receives scant attention

from Boltanski and Esquerre” (Fraser 2017, 63).

Hardt and Negri’s Assembly analyses multiple dimensions of

contemporary capitalism: finance capitalism, neoliberal capitalism, and

digital/cognitive capitalism. Their analysis suggests that these dimensions

interact. Although they do not say it explicitly, there are indications that

they see cognitive and digital capitalism as the dominant form and that they

therefore are closer to Boltanski and Esquerre than to Fraser in giving an

answer to the question in what kind of capitalism we live today: The “dominant

figures of property in the contemporary era – including code, images, cultural

products, parents, knowledge, and the like – are largely immaterial and, more

important, indefinitely reproducible” (Hardt and Negri 2017, 187).

Many critical theorists will be able to agree that capitalism is a

dialectical unity of a diversity of dimensions and forms of capitalism that

develop over time so that new aspects emerge, the relevance of certain aspects

shifts, etc. (see Fuchs 2014, chapter 5). My view is that in

order to decide which dimension is dominant at a specific point of time, we not

just require theory and philosophy, but also need to empirically study various

aspects of capitalism, which requires analysing primary and secondary data and

applying Marx’s theory empirically.

For example, one concrete empirical phenomenon, where one can ask what

dimensions of capitalism are present, are transnational corporations (TNCs). In

2014, 33.5% of the profits of the world’s largest 2,000 corporations were

located in the finance, insurance and real estate sector, 19.0% in the mobility

industries, 18.6% in manufacturing, and 17.3% in the information industry (see Fuchs 2016b, table 1). The data suggests that the structure of

transnational corporations is to specific degrees shaped by finance capitalism,

mobility capitalism, hyper-industrial capitalism and

informational/communicative/digital capitalism. But all of these dimensions

interact: Digital media corporations in Silicon Valley and other parts of the

world receive huge injections of venture capital (a specific type of finance

capital), aim at becoming listed on stock markets, and are prone to create

financial bubbles, as the 2000 dotcom crisis showed. Digital communication

advances and is at the same time a result of mobility and time-space compression

(Harvey 1989). As a result, the transport of people and

commodities has been growing. Digital commodities and digital commons are not

weightless, but require not just information work, but also the physical labour

of miners and assemblers in Africa and China, who are part of an international

division of digital labour (Fuchs 2014). Finance capitalism,

mobility capitalism, hyper-industrial capitalism and digital capitalism form a

dialectical capitalist unity that consists of interrelated, contradictory moments.

Capitalism is a unity of many capitalisms that develops dynamically and

historically. A dimension that makes the picture even more complex is

authoritarian capitalism, a form of capitalism that in recent times in the

context of the economic and political crisis of capitalism has become

strengthened, which poses the question how neoliberal capitalism and

authoritarian capitalism are related (Fuchs 2018).

Non-trivial questions emerge in this context that need to be addressed from a

Marxian perspective: What is authoritarianism? What is authoritarian

capitalism? How is it related to fascism, Nazism, right-wing extremism and

nationalism? Is Trump an authoritarian personality, an authoritarian

capitalist, a right-wing extremist, and a neo-fascist? How is the increased

prevalence of right-wing extremism, authoritarianism and nationalism related to

capitalist development (for a detailed analysis see Fuchs 2018).

Hardt and Negri stress the importance of the tradition of Western

Marxism (72-76), especially Georg Lukács and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who are

representatives of humanist Marxism. The focus on the human subject is indeed a

parallel between Autonomist Marxism and humanist Marxism. Both are concerned

with issues of subjectivity, social change and oppose dogmatic Marxism and

Stalinism. Hardt and Negri stress that Merleau-Ponty advanced a “critique of

Soviet dictatorship, which is presented as totalitarianism against

subjectivity” (75). One should in this context however not forget that the

early Merleau-Ponty (1947/1969) in Humanism and Terror justified

Stalinist terror and defined it as a form of humanism. Later, he clearly moved

away from this position and posited humanism against Stalinism.

Hardt and Negri argue that the tendency of the organic composition of

capital should not be seen as a deterministic law that results in the breakdown

of capitalism, but as a tendency that results in the rise of the general

intellect in capitalism (112-114, 203-206) so that “the general intellect is

becoming a protagonist of economic and social production” (114). Such a

theoretical move shows the connections between Das Kapital and Die

Grundrisse. There is therefore no need to stress “Marxism against Das

Kapital” (72). It is much more constructive to focus on the continuities

between both books. So for example the Grundrisse’s notion of general

intellect reappears in Das Kapital as allgemeine Arbeit (general

labour), Gesamtarbeiter (collective worker) and cognitive and

communicative aspects of work (Fuchs 2016c, 30, 36-37, 53-54,

171-172, 192-193, 239-240, 334, 364). Also class struggle is not alien to Das

Kapital, but an integral feature that Marx especially discusses in

historical passages that focus on struggles about the length and intensity of

the working day (see Fuchs 2016c, chapters 10 & 15). It

is therefore no accident that political readings of Das Kapital have

also emerged within Autonomist Marxism (Cleaver 2000).

3. Digital and Communicative Capitalism

Communication

and communications have in Marxist theory traditionally been treated as a

secondary, superstructural phenomenon of minor importance. As a consequence,

the critical theory of communication is today almost entirely associated with

Jürgen Habermas’ theory of communicative action that advances a dualist ontology

that separates work from communication and the economy from the lifeworld (Fuchs 2016a). Hardt and Negri are among those critical

theorists, who have given serious attention to the analysis of communication

and the digital in capitalism. Assembly continues in this vain. The

decisive point to make is not that everyone should agree with every aspect of

their analysis or to claim that digitality is the dominant reality of

capitalism, but that Hardt and Negri afford space and time to the analysis of

communication and the digital. The analysis of communication and digital

communication should not be left to the postmodernists, neoliberals,

Habermasians and Luhman(n)iacs, but rather be approached from the perspective

of Marxist theory (see Fuchs 2017, 2016a, 2016c, 2015b, 2014,

2011, 2008; Fuchs and Fisher 2015; Fuchs

and Mosco 2016a, 2016b). Hardt and Negri have made an important

contribution to the foundations of the emergence of communicative and digital

Marxism.

In Assembly, Hardt and Negri conceive of the digital as a

contradictory realm that poses both potentials for domination and liberation.

Digital communication plays a role throughout the entire book and is the

specific focus of chapter 7. Although Hardt and Negri do not like the term

dialectic, we can say that their analysis of digital communication is a

manifestation of a dialectic critical theory of communication that is both

opposed to the techno-determinism of techno-optimism and techno-pessimism (see Fuchs 2011, chapter 3, for a detailed discussion of this

distinction).

Hardt and Negri oppose their analysis of technology to the approaches of

Horkheimer/Adorno and Heidegger, whom they see as techno-pessimists (107-109).

There are, however, three important differences between Horkheimer/Adorno and Heidegger:

For

Horkheimer and Adorno, capitalism’s instrumental reason is the problem, not

technology as such, whereas Heidegger opposes all modern technologies and longs

for a pre-modern society without mass media, public transport and electronic

communications.

Adorno

did not oppose technology and in less well known works grounded foundations of

an alternative use of contemporary technologies for emancipatory purposes (Fuchs 2016a, chapter 3). A problem of the reception of

Horkheimer and Adorno is that there is too much focus on the Dialectic of

the Enlightenment’s culture industry-chapter, which overlooks other works.

The

publication of Heidegger’s Schwarze Hefte (Black Notebooks) has recently

shown that his thought was profoundly anti-Semitic, whereas Adorno was a

critical theorist of fascism and anti-Semitism and opposed fetishistic forms of

thought and action (see Fuchs 2015a, 2015c)

Hardt and

Negri discern among three phases of modern socio-technological development:

automation, digitisation and digital algorithms. In the latter phase,

algorithms play a key role in the organisation of exploitation, domination,

administration, surveillance and the emergence of digital Taylorism (131-133).

Since 2009, there has been a debate about how to

best understand digital prosumption and social media’s targeted

advertising-based capital accumulation models from a Marxist perspective.

Categories such as productive labour, rent, rent-becoming-labour, reproductive

labour and unproductive labour have in this context been utilised to the point

of theoretical exhaustion (see Fuchs and Fisher 2015, Fuchs 2014, and especially chapter 5 in Fuchs 2015

for an overview of the most common arguments and counter-arguments in the

digital labour debate). Hardt and Negri in Assembly take a clear

position on these questions: “Social media too have discovered mechanisms to extract value from the

social relationships and connections among users. Behind the value of data, in

other words, stands the wealth of social relationships, social intelligence,

and social production” (169). “Those astronomical stock valuations of digital

and social media corporations are not just fictional. The corporations have

sucked up vast reserves of social intelligence and wealth as fixed capital”

(287). The “processes of expropriating value established by such algorithms are

also increasingly open and social in a way that blurs the boundaries between

work and life. Google users, for instance, are driven by interest and

enjoyment, but even without their knowing it, their intelligence, attention,

and social relations create value that can be captured” (119).

Yet exploitation, expropriation and domination are just one side of

digital capitalism. Digital technologies are ambivalent and through the

contradictory development of the productive forces also advance the

socialisation of work and increase the co-operative character of life and

society. Hardt and Negri therefore oppose smashing digital machines. They argue

for the “reappropriation of fixed capital, taking back control of the physical

machines, intelligent machines, social machines, and scientific knowledges that

were created by us in the first place, is one daring, powerful enterprise we

could launch in that battle” (120). Appropriating fixed capital “is not a

matter of struggling against or destroying machines or algorithms or any other

forms in which our past production is accumulated, but rather wresting them

back from capital, expropriating the expropriators, and opening that wealth to

society” (287). Hardt and Negri stress the insight that given that technologies

are made by humans, they shouldn’t be left to capital and the state as tools of

domination, but should be transformed into tools of emancipation.

In later chapters of Assembly, it becomes evident that when speaking of the appropriation of fixed capital, Hardt and Negri have particularly the leaking of information (e.g. WikiLeaks), open access and the use of digital technologies in protests in mind (128, 214, 273, 294). Hardt and Negri’s analysis of the digital as contradictory is a contemporary manifestation of a dialectical analysis of technology. Marx grounded such a theory not just in the Grundrisse, but also in Capital Volume 1’s chapter on Machinery and Large-Scale Industry (see Fuchs 2016c, chapter 15). We need to add several qualifications to Hardt and Negri’s analysis of the digital (see especially Fuchs 2017):

-

The history of alternative media is a history of precarious, self-exploitative labour that has to do with the conundrum that fighting within capitalism against and beyond capitalism requires resources, which are more difficult to obtain when you do not work for-profit, but in self-managed, autonomous co-operatives. We therefore also need left radical reformist media politics that together with media activism advance radical media reforms (such as the taxation of digital advertising and digital corporations, a participatory media fee that redistributes capital and advertising taxation through participatory budgeting to non-profit media, etc.).

-

Given the dominance of individualism and the Californian neoliberal ideology in the digital industries and digital culture, there is a real danger that alternative projects (including free software, Wikipedia, WikiLeaks, platform coops, network commons, non-commercial open access, etc.) turn into lifestyle politics, individualistic clicktivism, the commodification of the digital commons and a libertarian form of capitalism. Such developments are no automatism, but are a danger that shows the need for political movements that strengthen and struggle for digital commonism.

-

Alternative digital media are not limited to progressive, left-wing phenomena such as Alternet, Democracy Now, The Real News, etc. Also the far-right has established its own alternative digital media that act as alternatives to the liberal mainstream media. Some far-right digital media, such as Breitbart and Drudge Report, significantly exceed the popularity, visibility and attention that left-wing digital media achieve. Communication struggles therefore need to not just focus on how to challenge the capitalist mainstream media’s power, but also on how to fight against far-right media (Fuchs 2018).

-

In the online world, the main power asymmetry does not concern the control of the means of digital production, but the capitalist attention economy: In the flood of information processed at high speed, alternative and critical knowledge has a much harder time to be visible and gain attention than the content advanced by tabloids, brands, corporations with large advertising budgets, celebrities, and entertainment corporations. Appropriating fixed capital therefore needs to entail the transformation of the digital towards a new logic that advances engagement, criticality and debate. We for example need online equivalents of Club 2, a new form of YouTube that becomes Club 2.0.

-

Besides alternative media, there is also a tradition of public service media that to a certain degree resists the logic of commodification and profit, but in many countries is prone to political particularism. Just like the Left should take power differently, it should also struggle not just for alternative digital media, but also a public service Internet that transforms the structures of public service media.

4. Politics

Recent

left-wing politics has seen a shift from the politics of occupations to the

politics of movement-parties. The movements supporting Bernie Sanders and

Jeremy Corbyn are the two most striking examples. Reflecting on the question

what kind of strategy and tactics today can best advance struggles for a

society of the commons, Hardt and Negri oppose one-sided left-wing politics. Assembly

argues that leaderless horizontality, centralised party politics, prefigurative

politics, radical reformism and revolutionary politics all have their limits,

problems and pitfalls. Hardt and Negri make arguments for a dialectical

politics that combines different forms, strategies and tactics of struggle.

In chapter 4, Hardt and Negri analyse contemporary far-right politics.

The aim of contemporary right-wing movements is to “restore an imagined

national identity that is primarily white, Christian, and heterosexual” (50). Hardt

and Negri argue that contemporary far-right politics often imitates left-wing

movements and are organised as leaderless and structureless movements so that

they are different from to classical right-wing movements. Donald Trump is

arguably the most influential far-right politician today. Trump, who is with

one mentioning almost absent in Assembly, certainly undermines

established party-structures. But at the same time he has used money, ideology

and popularity to build new structures. And he constitutes a new form of

authoritarian, right-wing leadership, in which the power of big politics and

big capital are fused in one person, the authoritarian spectacle mobilises

citizens via reality TV and social media, and a narcissistic self-branding

machine engages in constant friend/enemy-politics that takes symbolic political

violence to a new level (see Fuchs 2018). Trump is a

non-trivial far-right phenomenon that is neither completely new nor completely

old, but a development of the strategy and tactics of the far-right.

Hardt and Negri argue both against leaderless

horizontality that rejects organisation and institutions and against

centralised authority in progressive movements. “Theoretical investigations,

for instance, of the increasingly general intellectual, affective, and

communicative capacities of the labor force, sometimes coupled with arguments

about the potentials of new media technologies, have been used to bolster the

assumption that activists can organize spontaneously and have no need for institutions

of any sort” (7). Political leaders of social movements have often been

repressed externally by violence and ideology (9) and internally by

anti-authoritarianism (9-10). Hardt and Negri also oppose vanguard parties and

pure electoral parties. “Progressive electoral parties, in the opposition and

in power, can tactically have positive effects, but as a complement to not a

substitute for the movements” (8). They call for an inversion of roles that

gives “strategy to the movements and tactics to the leadership” (18).

They speak of tactical leadership as leadership that is “limited to short-term

action and tied to specific occasions” (19). Hardt and Negri make an argument

that social movements should “strive not to take power as it is but to take

power differently” (xiii-xiv). Taking power entails building new institutions

beyond representative democracy and building new democratic institutions. The

two authors stress the complex relation of centralised Power

(potestas/pouvoir/poder/Macht) and power as potential

(potentia/puissance/potencia/Vermögen).

Hardt and Negri argue for a political strategy that combines

prefigurative politics, antagonistic reformism and taking power to overthrow

existing institutions and create new democratic ones (274-280). Employing just

one of these forms of politics often faces problems and limits. Assembly argues

for the complementarity of the three political strategies: “The taking of

power, by electoral or other means, must serve to open space for autonomous and

prefigurative practices on an ever-larger scale and nourish the slow

transformation of institutions, which must continue over the long term.

Similarly practices of exodus must find ways to complement and further projects

of both antagonistic reform and taking power” (278). Example projects that such

a complementary left-wing politics could struggle for include guaranteed basic

income as “a money of the common” (294) and “open access to and democratic

management of the common” (294). Such a form of left-wing politics constitutes

a new Machiavellian Prince that does not put Power, but the common first

(chapter 13).

In more concrete terms, Hardt and Negri argue for a politics of

left-wing convergence, in which unions and social movements converge into

social unionism that organises social strikes against the exploitation of the

social production of the common.

Isn’t the

left-wing politics that Hardt and Negri argue for a kind of Luxemburgism 2.0 in

the age of the social production of the common? Rosa Luxemburg in her time argued

against Eduard Bernstein’s pure parliamentary social democratic reformism. She

opposed anarchist individualism and propagated using the mass strike as

political tactic. Luxemburg neither rejected nor fetishished parliamentary

politics. She rejected Leninist vanguard party politics and argued for

organising the spontaneity of protest. She opposed war, imperialism and

nationalism with internationalist politics. She saw that the limitation of

democracy in post-revolutionary Russia was a serious shortcoming that would

create major problems. Luxemburg argued for dialectics of party/movements,

organisation/spontaneity, leader/masses (see Luxemburg 2008).

The point, where we need to transcend Luxemburg’s politics today is that she

was very sceptical about the feasibility of autonomous projects, especially

co-operatives. Self-management cannot start from nothing in a new society. It

needs social forms that germinate in capitalism and produce seeds that as a

common point beyond profit and wage-labour.

Hardt and Negri oppose both neoliberal entrepreneurship that resonates

“especially in the digital world of dotcoms and start-ups” (142) and social

entrepreneurship that is a “social neoliberalism” (145) that outsources welfare

state to voluntary action, charities, and communities. “The nexus of social

neoliberalism and social entrepreneurship destroy community networks and

autonomous modes of cooperation that support social life” (146).

Hardt and Negri understand politics as not just taking place on the

streets, in factories, squares and offices, but also in the realm of language

and communication. They argue that we must politically take and transform the

meaning of words and argue that “transforming words themselves, giving them new

meanings” (151) is part of political struggle. “Sometimes this involves coining

new terms but more often it is a matter of taking back and giving new

significance to existing ones” (151). “Indeed one of the central tasks of

political thought is to struggle over concepts, to clarify and transform their

meaning” (xix)

In this vein, Hardt and Negri argue for transforming the meaning of

entrepreneurship. Chapter 9 is dedicated to the “Entrepreneurship of the

Multitude”. “It is important to claim the concept of entrepreneurship for our

own” and not leave it to neoliberal managers and gurus (xix). By the

“democratic entrepreneurship of the multitude”, Hardt and Negri understand the

politics of social unionism (social movements + unions) that organises social

strikes. Social unions entails “organizing new social combinations, inventing

new forms of social cooperation, generating democratic mechanisms for our

access to, use of, and participation in decision-making about the common”

(xix). The entrepreneurship of the multitude aims at “self-organization and

self-governance” (146). “Social unionism […] by combining the organizational

structures and innovations of labor unions and social movements, is able to

give form to the entrepreneurship of the multitude and the potential for revolt

that is inherent in social production” (224).

The transformation of meanings associated with words as political

strategy can certainly work for terms such as democracy, freedom, liberty,

human rights, or the republic. But does it work for the term entrepreneurship?

Or the nation? Or capitalism? It would for example be absurd and confusing to

argue that we need to construct communism as a different capitalism. The word

“capitalism” is so much engrained with the meanings of exploitation and class

that trying to appropriate it might very well turn out to be counterproductive.

So what about the meaning of entrepreneur, entrepreneurial and

entrepreneurialism?

Ernst Bloch suggests fighting the Nazis and fascism should also entail

symbolic struggles over words so that communists and socialist appropriate the

words that fascists use and give them a different meaning. He argued that the

words home and homeland (Heimat) should not be left to the fascists, but

be used differently: Capitalism alienates humans from society, nature and

themselves as their home. Socialism (or what today we could call commonism or a

commons-based democracy) is in contrast for Bloch a true homeland that

overcomes capitalism and the particularism of nationalist homeland ideology:

“But the root of history is the working, creating human being who reshapes and

overhauls the given facts. Once he has grasped himself and established what is

his, without expropriation and alienation, in real democracy, there arises in

the world something which shines into the childhood of all and in which no one

has yet been: homeland” (Bloch 1995, 1375-1376).

Hardt and

Negri are like Ernst Bloch intransigent optimists, who use the construction of

hope as a political weapon in the struggle for alternatives and believe in

creating concrete utopias of the common as projects of class struggle.

Commonism is a not-yet. The struggles of the multitude are the struggle for

realising a political not-yet.

In countries, where right-wing extremists win elections and are a major

threat, giving a progressive meaning to the terms home and homeland is a

feasible political tactic in order to try to win over protest voters who are

afraid of social decline. The far-right populist Norbert Hofer almost won the

2016 Austrian presidential election. His party, the Freedom Party (FPÖ), has

for many years campaigned against immigration by presenting migrants as a

threat to the Austrian homeland. Figures 1 and 2 show two examples, in which

Islam and Moroccan immigrants are presented as criminals and enemies to the

homeland.

Figure 1: Election poster of the Freedom Party of Austria (“Love of the

Homeland instead of Moroccan Thieves”)

Figure 2: Election poster of the Freedom Party of Austria (“Homeland instead of

Islam”)

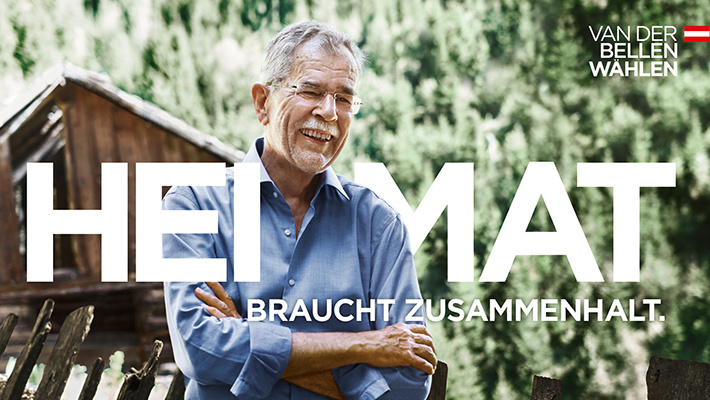

The Green

Party candidate Alexander Van der Bellen in the 2016 Austrian

presidential

election appropriated the term homeland and gave a different meaning to

it:

Social security and solidarity (see figures 3 and 4). He won the

run-off

election against Hofer and became Austrian president. Constructing a

different

meaning of the word “home” was used as linguistic and communicative

tactic to

counter the threat of far-right politics. Under specific

political conditions, such as the presence of strong right-wing

extremist parties, culture jamming, linguistic détournement and

semiotic struggle form a feasible method of political struggle.

Figure 3: Election poster of Alexander Van der Bellen in the Austrian

Presidential Election 2016 (“Homeland needs solidarity”)

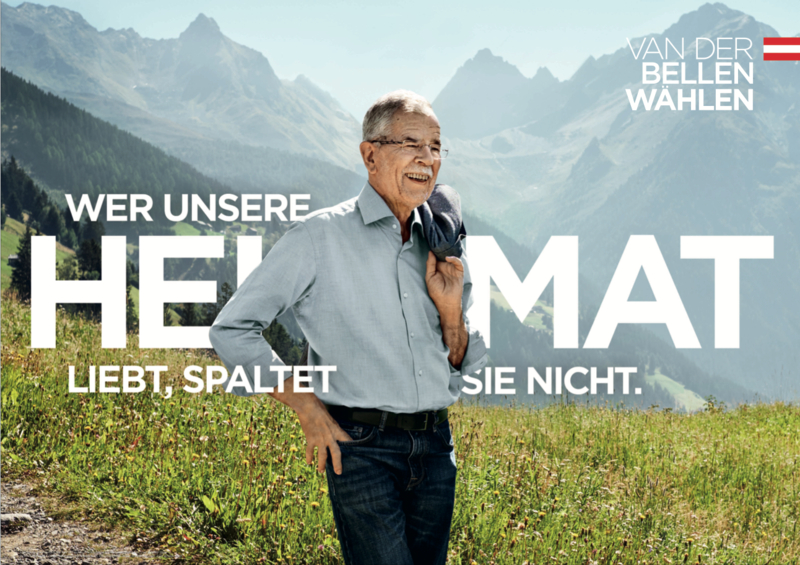

Figure 4: Election poster of Alexander Van der Bellen in the Austrian

Presidential Election 2016 (“Those who love our homeland, do not divide it”)

But can the

same strategy work for the word entrepreneurship? The term entrepreneur comes

from the Old French entreprendre that means to undertake and begin

something. The term was introduced to the English language in the early 19th

century. In the world of classical political economy, Jean-Baptiste Say

introduced the term of the entrepreneur in the early 19th century in

his book A Treatise of Political Economy (Traité d'économie

politique) that was first published in 1803:

The entrepreneur “employs, disposes of, and wholly consumes” capital, “but in a

way that reproduces it, and that with profit” (Say 1971/1821,

113). 200 years later, the Encyclopaedia Britannica understands entrepreneurs as the “business class” and the entrepreneur as the “businessman” (Cornwall 2010).

It claims that economic growth takes place “under

the leadership of an entrepreneurial class”. Entrepreneurs according to this

understanding undertake “enterprise investment” that aims at the “growth in

labour productivity and GNP” (Cornwall 2010).

Over more than 200 years, the term entrepreneur has been used in an

individualistic and capitalistic manner for signifying an individual capitalist

who invests and accumulates capital and exploits workers. Is it realistic that

now the different political meaning of social unionism can be given

successfully to this bourgeois term that signifies individualism and

capitalism? There are certain terms that are so corrupted that they should better

be discarded than appropriated. It would also not make sense to try to redefine

what capitalism is and to give a new meaning to this term. The effect would be

that everyone would think one justifies capitalism and does not want to abolish

it. We need some words that signify what we oppose. Capitalism and

entrepreneurialism are among these negative terms that cannot in a meaningful

way undergo a determinate linguistic negation. The risk of appropriating the

terms entrepreneur, entrepreneurial and entrepreneurship for progressive

purposes is that it is misunderstood as encouraging the commodification of

activism. Social unionism is an important political strategy, but it can be

called by that name. We do not need a bourgeois category for it. Why do we for

instance not instead of speaking of political entrepreneurship and the

entrepreneurship of the multitude, use as Paolo Gerbaudo (2012)

suggests, the terms political choreography and the choreographers of the

multitude?

5. Conclusion

Hardt and

Negri’s Assembly is an important intervention into contemporary

politics. It advances a critical analysis of contemporary capitalism that is

shaped by neoliberalism, finance capital, nationalism, right-wing extremism,

the common, co-operation, immaterial labour, the digital, algorithms, digital

labour, digital assemblages, digital domination, and digitally mediated social

struggles. Hardt and Negri are ruthless critics of capitalism and bureaucracy

as well as intransigent optimists, who care about the next steps in progressive

social movement politics.

Assembly argues for rethinking left-wing strategies and

tactics. Its authors criticise one-sided approaches and argue for dialectics of

movement/leadership, spontaneity/organisation, revolution/reform. The

appropriation of fixed capital is an important feature of the suggested

strategy and tactics. Hardt and Negri term this politics the new Prince and the

entrepreneurship of the multitude.

The key strength of the book is the multitude of dimensions, ideas and

provocations that the analysis advances, which makes it a book that will be

read by many activists, citizens, scholars and other (im)material workers, who

care about a better future and are looking for ways to transform society in

progressive ways. Assembly is a brave and intelligent intervention that

will influence our debates, struggles, theories, critiques, praxis, strategies

and tactics in the coming years.

References

Bloch, Ernst. 1995.

The Principle of Hope. Volume Three. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Boltanski, Luc and

Arnaud Esquerre. 2017. Enrichment, Profit, Critique. A Rejoinder to Nancy

Fraser. New Left Review 106: 67-76.

Boltanski, Luc and

Arnaud Esquerre. 2016. The Economic Life of Things. Commodities, Collectibles,

Assets. New Left Review 98: 31-54.

Cleaver, Harry.

2000. Reading Capital Politically. Leeds: Anti/Theses.

Cornwall, John L. 2010. Economic Growth. In Encyclopaedia

Britannica Online, https://www.britannica.com/topic/economic-growth

Fraser, Nancy.

2017. A New Form of Capitalism? A Reply to Boltanski and Esquerre. New Left

Review 106: 57-65.

Fuchs, Christian.

2018 (in press). Digital Demagogue: Authoritarian Capitalism in the Age of

Trump and Twitter. London: Pluto.

Fuchs, Christian.

2017. Social Media: A Critical Introduction. London: Sage. 2nd

edition.

Fuchs, Christian. 2016a. Critical Theory of Communication: New

Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the

Internet. London: University of Westminster Press.

Fuchs, Christian.

2016b. Digital Labor and Imperialism. Monthly Review 67 (8): 14-24.

Fuchs, Christian.

2016c. Reading Marx in the Information Age. A Media and Communication

Studies Perspective on “Capital Volume I”. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2015a. Anti-Semitism, Anti-Marxism, and Technophobia:

The Fourth Volume of Martin Heidegger’s Black Notebooks (1942–1948). tripleC:

Communication, Capitalism & Critique 13 (1): 93–100.

Fuchs, Christian. 2015b. Culture and Economy in the Age of Social

Media. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2015c. Martin-Heidegger’s Anti-Semitism: Philosophy of

Technology and the Media in the Light of the “Black Notebooks“.

Implications for the Reception of Heidegger in Media and Communication Studies.

tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 13 (1): 55–78.

Fuchs, Christian.

2014. Digital Labour and Karl Marx. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian.

2011. Foundations of Critical Media and Information Studies. Abingdon:

Oxon.

Fuchs, Christian. 2008. Internet and Society: Social Theory in the

Information Age. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian and Eran Fisher, eds. 2015. Reconsidering

Value and Labour in the Digital Age. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fuchs, Christian and Vincent Mosco, eds. 2016a. Marx

and the Political Economy of the Media. Leiden: Brill.

Fuchs, Christian and Vincent Mosco, eds. 2016b. Marx in the Age of

Digital Capitalism. Leiden: Brill.

Gerbaudo, Paolo.

2012. Tweets and the Streets. Social Media and Contemporary Activism.

London: Pluto.

Hardt, Michael and

Antonio Negri. 2017. Assembly. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, David.

2017. Marx, Capital and the Madness of Economic Reason. London: Profile

Books.

Harvey, David.

2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, David.

1989. The Condition of Postmodernity. An Enquiry into the Origins of

Cultural Change. Oxford: Blackwell.

Harvey, David,

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. 2009. Commonwealth: An Exchange. Artforum

48 (3): 210-221.

Luxemburg, Rosa.

2008. The Essential Rosa Luxemburg. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Merleau-Ponty,

Maurice. 1947/1969. Humanism and Terror. An Essay on the Communist Problem.

Boston: Beacon Press.

Say, Jean-Baptiste.

1971/1821. A Treatise on Political Economy. New York: Kelley.

About the Author

Christian

Fuchs is a critical

theorist of communication and society. He is professor at the University of

Westminster and co-editor of the journal tripleC: Communication, Capitalism

& Critique (http://www.triple-c.at).

@fuchschristian http://www.triple-c.at