Bogdan Osolnik was born on 13 May 1920 in Borovnica, at the time part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. In 1942, he became a journalist in the (then illegal) press of the anti-fascist resistance. After the liberation of Yugoslavia, he was editor-in-chief of Ljudska pravica [People's justice], a correspondent of the Tanjug press agency, and in 1951 he became the director of the newly established Radio Jugoslavija radio station. In 1958, he was appointed Secretary of Information of the Federal Executive Council of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY). In this position, he was responsible for preparing the Law on Freedom of the Press and Other Means of Information, which in 1960 laid the foundations for the democratisation of this sphere of public life in Yugoslavia. He was the initiator of the foundation of the Yugoslav Institute of Journalism that provided education for journalists from developing countries. He was a member of the Steering Committee for the first Conference of Heads of State and Government of Non-aligned Countries in Belgrade (1 September 1961) responsible for information, and this marked the beginning of his activity in the area of communication in the Non-Aligned Movement.

In 1962 he helped establish the first university institution for the education of journalists in Yugoslavia. He became Head of the Department of Journalism at the then School of Political Sciences in Ljubljana (today the Faculty of Social Sciences), where he lectured on the subjects Public Opinion and Sociology of Mass Communication from the foundation of the Department of Journalism until 1966. In the first year, he was also president of the Fund for Journalism at the Department of Journalism. He also lectured on the subjects of Sociology of Mass Communication and Public Opinion at the School for Political Sciences in Belgrade.

He was one of the pioneers of theoretical and practical research of public opinion in the Yugoslav socialist society. During his pioneering work in the field of media and communication studies, he came into contact with a number of media and communication researchers from other countries. In 1970, in the German town of Konstanz, when Jacques Bourquin won his fourth presidential mandate, he was chosen as vice-president of the International Association for Mass Communication Research - IAMCR, which even today remains perhaps the most important organisation in the field of media and communication research. He remained in this capacity until 1980. He was also president of the International Communication Section of that same association, which he helped establish at the IAMCR symposium in Ljubljana in 1968. Its purpose was to study the media in the context of international communication. Osolnik was actively involved in preparation of the 1966 IAMCR conference in Herceg Novi, which Kaarle Nordenstreng and Cees Hamelink in their IAMCR retrospective described as a turning point for the organisation. In addition, Bogdan Osolnik was a member of the Yugoslav National Commission for UNESCO and led its Committee on Information for many years. Later, he remained as a standing member of the committee.

The international symposium on the subject of information and international understanding, which he helped organise in Ljubljana in cooperation with IAMCR and UNESCO, was attended by researchers and journalists from 26 countries. The discussion and conclusions at the symposium demonstrated the far-reaching impact of new communication technologies on cultural and social life as well as on international relations, and thus the need for a thorough questioning of the status quo in the field of international information flows. Based on the these ideas, Osolnik, who was a member of the Yugoslav delegation, advocated at the fourteenth General Assembly of UNESCO held in Paris in 1968 that UNESCO engages in comprehensive research of the impact of modern communications on social life, not only on culture, but also on the whole of development and international relations. This approach was supported by the Canadian, French and some other delegations, which led to UNESCO becoming significantly more active in this field. A meeting of experts on communication in Montreal under this programme opened new perspectives for the further engagement of UNESCO in the field of information, which had a considerable impact on development of the initiative for the New World Information and Communication Order, or NWICO.

During his many years of cooperation with UNESCO, Osolnik was involved in all stages of preparation of the Declaration on Fundamental Principles concerning the Contribution of the Mass Media to Strengthening Peace and International Understanding, to the Promotion of Human Rights and to Countering Racialism, Apartheid and Incitement to War. He worked as a coordinator of delegates from non-aligned countries and participated in the final redaction of the declaration at the General Conference in Paris in 1978, when this important document was adopted by consensus.

At the request of the Director-General of UNESCO, in 1977 he became a member of the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems - the so-called MacBride Commission. The Commission's task was to prepare a comprehensive study on the state of communications in the world and on the policies of their further development. The result of the work of the Commission was a report published in monograph form under the title Many Voices One World: Communication and Society Today and Tomorrow. In the preface, the Commission's Chairman, Sean MacBride, specifically points out Bogdan Osolnik's contribution to the Commission's work. He was especially active in elaborating all aspects of the new international order in the field of information and communication as a process of building new, more equal and fairer relations in which there would be greater freedom and actual opportunities for communication between nations and between individuals. He developed his views in his study The New International Information and Communication Order (1981), which was also published in several foreign languages in an edition of the Yugoslav newspaper Međunarodna politika [International Politics].

At the twenty-first General Assembly of UNESCO in Belgrade in 1980, as a member of the Yugoslav delegation and the coordinator of the delegations from non-aligned countries Osolnik contributed to establishing the principles of the new international information and communication order in a Resolution on the report of the Director-General on the findings of the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, which was adopted by consensus. In the same way, he contributed to the Resolution's adoption by which the International Programme for the Development of Communication was established.

In 1981, he was elected a full professor of international communication at the University of Ljubljana. He has participated in several national and international conferences on the subject and lectured at various foreign universities, including the University of Leuven, at Charles University in Prague, and at the Institute of Journalism in Munich.

As a member of the Yugoslav Federal Parliament from 1969 to 1982, he advocated the creation of a democratic system of communication in Yugoslav society, all the while not giving up teaching and journalism. In a number of articles published in Yugoslav newspapers, he dealt with the question of the role of communication in the self-managing socialist society, of the process of shaping public opinion and its impact on the development of society, of the normative regulation of the sphere of information, of the issues of freedom of information and ethics of public speech, and of the impact of communication technologies on social life.

We spoke with Bogdan on 8th of October, 2015, at his home in Ljubljana, while making some additional clarifications later, when we finished the interview. The interview was translated from Slovene to English by Marko Kozar, with additional editing and proofreading done by Murray Bales.

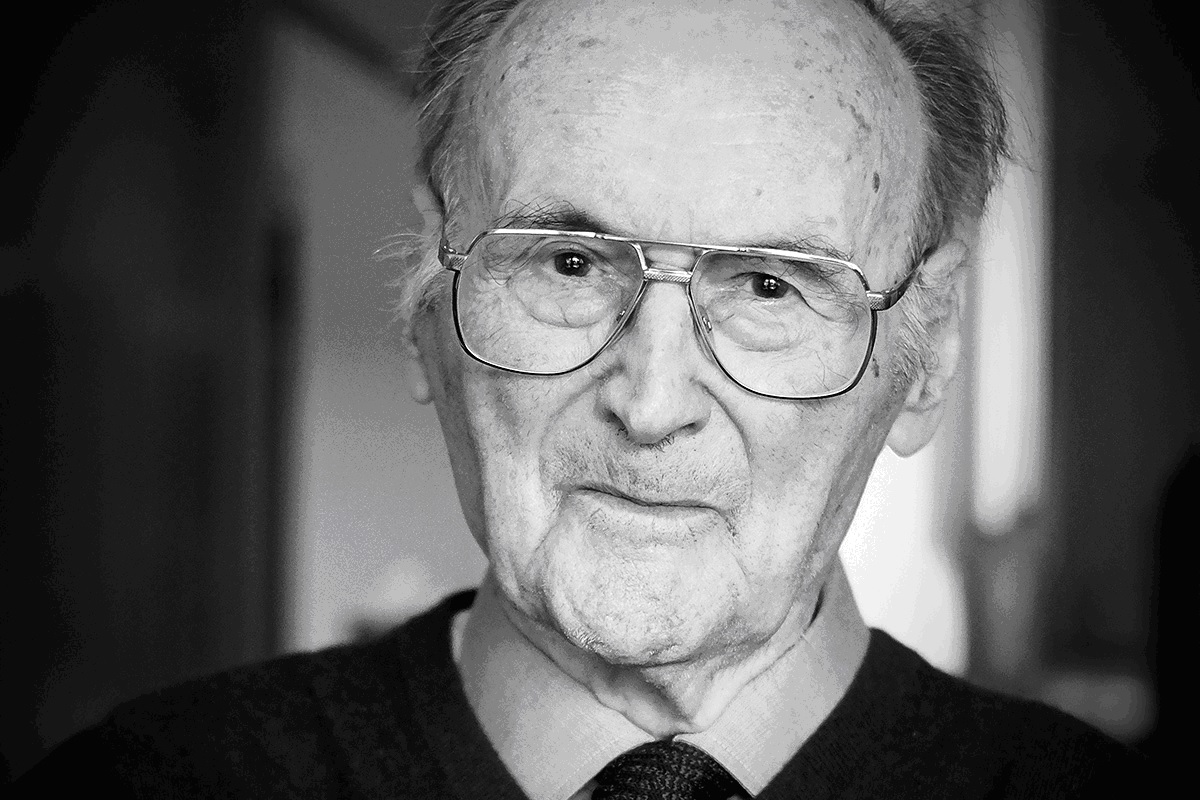

(Photo: Jernej Amon Prodnik)

Sašo: How did you become interested in questions of communication?

Bogdan: I entered the world of communication during World War II when information was very important, especially for us as members of an occupied nation. We had been cut off from the world and were prevented from communicating in our own language. The occupying forces seized our radios so that we could not listen to the international news and so on.

That's when underground communications developed in our resistance movement. We developed many techniques for reproduction, as it was called at the time, as well as genuine print shops. We also had a wide courier network that made it possible for the materials to get from the print shops to the people. Parallel to the cultural colonisation system of the occupying forces, there existed an underground system of anti-fascist communication, and I would say that this was in fact the first front of our resistance, through which many people passed. The movement affiliation usually began by someone accepting to deliver our newspapers like Poročevalec [Reporter], despite the mortal danger associated with this activity.

Then the authors who turned into partisan journalists started to appear, even though they had not been educated for such work. I was one of them. Just before the end of the war, I became the editor of the Ljudska pravica [People's Justice] newspaper and had some very nice colleagues. Bojan Štih was my assistant editor. Also among the members were the writers Miško Kranjec and Cene Kranjec and some others who, led by patriotic feelings, agreed to participate in the press.

Sašo: Did you continue your work after the end of the war?

Bogdan: Yes. The end of the war naturally meant we would get a chance to operate the print shops that had now passed into our hands, which was of course a giant leap. Despite all the good intentions, we were not technically ready for the take-over of modern print shops. We started to prepare for the new job with the help of the typesetters and other workers who remained there.

This transition was very difficult, especially because the sources of information were not organised. We received information mainly from our regular collaborators and from their acquaintances and so on. Especially delicate was the verification of information about foreign affairs. As the editor-in-chief of Ljudska pravica, for example, I wrote an aggressive article on how we were going to resist the withdrawal of the Partisan army from Trieste. In the evening, when Boris Kidrič saw this, he jumped to his feet and said: "You don't know, but just today at Tito's request we agreed to withdraw the forces because he said that we could not afford to cook up a new world war". And then he added that they had forgotten about the journalists (laughter). This is just an example of how difficult the work was. Everything was improvised. The print shop was of the old type and everything was done with lead. Lead plates were prepared during the day and they went into the machine close to midnight, so I was receiving doses of lead myself as well because I wanted to participate in the whole process of the copy. Because of that I became ill. I already had lung problems from the partisan times and this finally forced me to give up that work. I did not intend to become a professional journalist anyway.

Then I was a political worker and did what I had been doing when I had been a partisan. I was a political activist of the Liberation Front. First in Gorenjska, like back in the partisan times, and then in Dolenjska in Novo mesto.

Then, suddenly, I was given a new task. In 1946 I was called to Ljubljana. There I was received by Edvard Kardelj, who was then the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Yugoslav government. He told me they intended to send me on a very important mission related to the peace treaty with Austria. Namely, that Yugoslavia would demand the annexation of Carinthian Slovenians to the Slovenian nation and that it would be very important to inform not only the Slovenian public, but also the Yugoslav one and possibly also the foreign public for our demand to come true. He was very convincing. I intended to devote some time to my personal questions, but he said: "This is the last opportunity, a historic opportunity to save the Carinthian Slovenians from Germanisation".

They recalled me at the end of August, after almost nine months, when a further conference had shown that the Yugoslav demand would not be realised. At the same time, the disagreement began between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, the so-called Cominform dispute, had broken out and it was even clearer that the Soviet Union would not support Yugoslavia in the international field. In 1949, there was a conference of foreign ministers in Paris where the Soviets renounced their support and said that they had voted for the resolution prepared by Western countries, and that now the only question was how the State Treaty with Austria would be formulated.

When I returned, I asked Kardelj: "Were the things we sent from Carinthia of any help to you?" These were various historical documents, declarations and so on. Kardelj's answer was curt: "You know what the minister said?" He meant the then Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union, Vyshinsky. "This is just paper. It would be something else if blood was spilled." And then he added: "The Soviet Union wants imperialism to bleed wherever possible." I was astonished. First, I thought this was a critique of my work and the work of the regional committee. But I immediately calmed down because I told myself that surely they knew I would never support bloodshed after what we had experienced in that terrible war.

Jernej: How did you return to questions of communication?

Bogdan: It was the time of the Cold War and there was a feeling of terrible tension and war on the airwaves. The Soviet Union in particular used radio as a way to build a campaign against Yugoslavia, accusing the Yugoslav leadership and urging the people of Yugoslavia to renounce such authority. Our services were receiving these attacks and I must say that at times the Soviets were quite disgusting, calling us American agents, denying our struggle against Nazism, saying that Yugoslavs were German agents in the concentration camps and all sorts of things. At that time, we of course cut diplomatic relations with them and their affiliated countries.

The West did not provide any help because many thought that this was a pre-arranged game between the Soviets and us. I led one of the journalist delegations to England and this was the first question they asked. Our task was to present the depth of this conflict and that these were already two different systems, and that we were certainly willing to defend the freedom and the democracy of our development.

In response to these attacks Radio Jugoslavia was established. The primary intention was to inform foreign audiences so, in addition to Yugoslav languages, we were also broadcasting in six additional languages. That meant the two minorities' languages, Italian and Hungarian, along with German, French, Russian and Spanish. Of course, the broadcasting and the success of the broadcasting depended heavily on how well we would get accustomed to the situation in those countries, the lives of their people, and what we would focus our attention on, as well as which parts of our history and our present we would present to those nations.

When working for Radio Jugoslavija I got somewhat involved with diplomacy because press coverage involved cooperation with experts on those countries, thus in a way I was already close to diplomacy. At that time, we also needed to improve our relations with Western countries, especially West Germany, with which we had established our principal economic relations. I was sent to Bonn to our embassy in the Federal Republic of Germany as a political advisor, mostly to make contact with social organisations, trade unions, social democrats and others to deepen our economic relations and to overcome the distrust of Yugoslavia that was still present in those countries, including Germany. We were still regarded as part of the Soviet bloc.

I wasn't happy in Bonn. It was a lifeless bureaucratic town. I requested a transfer to the position of Consul-General in Munich. Here I was closer to Slovenia and life was livelier. Political and economic life as well as economic relations with Slovenia were very lively.

Sašo: During this time, was there similar hostile communication by the West as there had been by the Soviet Union?

Bogdan: We know from literature that the Truman Administration adopted a policy of 'keeping Tito afloat' (laughter).[1] They provided just enough help so that Yugoslavia didn't sink under the burden. And only later came the talks and the aid in the form of food and weapons.

Sašo: What changes did you experience when relations with the Soviet Union improved?

Bogdan: When Stalin died in March 1953, a question was raised of what would happen with the Soviet Union and what the consequences for Yugoslavia might be. Just then, Kardelj and Vladimir Bakarić were on their way via Munich. They had given a lecture on self-management for the Social Democrats in Sweden. They stopped at my place in Munich because it was the time of Oktoberfest (laughter). They both believed some change was very likely to happen since the young followers of Stalin could not afford the same methods of governing that the autocrat Stalin had introduced. Kardelj also told me that because of that I would be sent to our embassy in Moscow as a diplomat so that we could monitor these things and regulate the relations with the Soviet Union in a slightly different manner than before. Soon after, I was indeed appointed as Minister Counsellor at the Embassy of Yugoslavia and at the end of 1954 came to Moscow.

There I encountered a state of war psychosis. West Germany had just joined NATO and the Russian media was spreading the rumour of that being the first step towards a new attack on Russia. People began stocking up on food, there were international memorandums, not only by the government, but also by the Orthodox Church, academics and so on. They were all turning to the European public to prevent another attack.

Then I experienced something that diplomats rarely experience - the new Soviet leadership under Khrushchev really felt the need to normalise relations with Yugoslavia. They actually wanted to overcome the isolation that Stalin's politics had led the Soviet Union into. Khrushchev stood at the forefront of a new course to find a way and restore diplomatic relations.

I have written about the details of these meetings before,[2] but let me mention just one, when Ambassador Dobrivoj Vidić and I raised the issue of the Peace Treaty with Austria. The Soviet Union had been hindering the adoption of the treaty which had been lying in a drawer for six or seven years. When the Soviets claimed they could not talk about peaceful coexistence since Germany was allegedly arming itself for a new attack on the Soviet Union, I firmly and sharply told Khrushchev that I had just arrived from Germany and that I had witnessed the recent elections, that there was broad support for peace, that the Social Democrats had received nine million votes in the elections and that what he was saying was simply not true. This made the Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, who was also present at the meeting, shudder. Khrushchev went silent, but in a few weeks he appeared at a reception and came straight over to Vidić and myself and said: "Let's sign the contract with Austria!".

What had happened? They realised they had to make direct contact with the Yugoslav leaders and demonstrate a change in their politics. They were so hasty that on 15 May of the following year the Peace Treaty with Austria was signed in Vienna. On 26 May they took a plane to Belgrade and proudly presented this document as proof: "There you have it, we have started to arrange matters".

After Stalin's death, many things changed in the field of information as well. In particular, they were no longer attacking Yugoslavia. That was settled. They even decided to publish something positive. I suggested to their company for foreign literature to publish a booklet on the national liberation struggle of Yugoslavia, which was translated by the historian Jovan Marjanović. And they actually published it. After many years, this was the first positive book about Yugoslavia.

When some of our experts came to see the Soviet archives, they discovered that their libraries had been completely cleansed of everything related to Yugoslavia. Before Tito's arrival, their musicians turned to us asking if we had any music notes because they didn't have any music notes for the Yugoslav anthem. We didn't have the notes either, but we advised them to play the Polish anthem, which had the same melody, with less beat and at a slower pace. They asked for someone from the embassy to come and show them what the Polish anthem sounded like, so the ambassador sent me because he had heard I once played the violin. And so I came to the theatre and was honoured to intone the first few bars for the Soviet orchestra, who had in front of them the notes for the Polish version of the Hej, Slovani anthem.

What can I say? It was difficult to change what had been spoken and written about the Soviet Union in Yugoslavia. The key moment was the arrival of the Yugoslav delegation led by Tito and Kardelj to Moscow upon the Soviet invitation. This is when the ceremonies began. This is when the restoration of fraternity started. I accompanied President Tito on the way to Stalingrad and that train ride was a special experience. Stations were packed with people, some were even standing on the rooftops. I was afraid that the rooftops would collapse and that there would be accidents, but everything turned out okay.

Jernej: When did you occupy yourself with communication issues again?

Bogdan: My work in the Soviet Union ended soon. Two years later, I received a notice from Belgrade informing me that a new executive council had been elected and that they wanted me to become the Secretary of Education and Culture. I was hesitant because I felt that additional work in Moscow would soon be needed, that the festivities then held would not be permanent and that new problems would arise. The field of culture and education, however, was also very tempting so I quit my job at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and in the autumn of 1957 went to Belgrade to pursue the new job.

I must say that the Secretariat of Culture was something completely different from a Ministry. Boris Kidrič in particular argued that the questions of culture, education and economics were in the domain of individual republics, and that they did not require any ministry at the federal level, rather only coordinating bodies so that the republics would be well connected. I shared the opinion and worked in that way, mainly meeting with representatives of republics in the field of culture, ministers of culture, representatives of academies and so on.

This job also involved a lot of activities with communication characteristics. Among other things, we were the authors of cultural conventions with countries that had broken off relations with Yugoslavia because of the Cominform dispute, and I was the proposer and signatory of the first cultural convention with Czechoslovakia. Even the question of informing our own public was closely related to educational problems. At the time, a large part of the population in Yugoslavia was still illiterate. The illiteracy level among women, especially in the southern part of the country, was as high as 80 percent in some places. I pushed for our educational activities to be linked to cultural ones as much as possible, not only in terms of increasing literacy, but also in terms of cultural activities, which also requires school education.

Before introducing a reform of education we did a lot of preparatory work. My task was to finish up the four-year work on this reform. I must say that cooperation with UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, was very helpful. They provided us with a lot of valuable material on how the areas of education and cultural education were organised in other countries.

When my work came to an end, new elections took place and the Executive Council was reorganised. I was appointed Secretary of Information. The work of the Secretary of Information brought me to a field I really liked. I must say that the timing was also very appropriate for it. It was the time of an ongoing information revolution. New media were appearing. I was in contact with our comrades in the Republic of Slovenia who operated under the auspices of the School of Political Sciences that later became the Faculty of Social Sciences, especially with comrade France Vreg, who had been my friend since the Partisan times. His partisan name was Mile. Vreg struggled with all his might to put more attention to journalism and to educate journalists for this work. In fact, all the staff that worked in this field were either from the partisan or post-war times. They lacked knowledge of the new communication technologies and general and university education were poor as well. And I was witnessing all of this. I was coming to Ljubljana from Belgrade and was also giving lectures at the new Department of Journalism, established at today's Faculty of Social Sciences in Ljubljana.

Jernej: You helped establish the Department?

Bogdan: Vreg and I established it together, and also addressed concrete questions. It wasn't easy to find lecturers. It wasn't easy to begin to addressing communication as a theoretical question, a sociological question.

To establish a new department, we also had to provide the necessary financial resources ourselves. Radio Ljubljana and the newspapers were interested in training their personnel or hiring new staff with an appropriate education so they contributed to the Fund for communications, with which we funded the lectures, as well as all the necessary teaching aids and literature.

As a State Secretary, I was lucky to be invited on a semi-tourist visit to the United States. I skipped the tourist programme and instead asked if I could visit four universities with the most intense activity in the field of journalism. And it was made possible. They also provided me with books with which I armed myself for work, for a detailed study of communication issues. When I came back, our School of Journalism had already been established. It was the first School of Journalism in the Balkan area and, in addition to the Polish one in Warsaw, the only School of Journalism in the socialist countries.

Jernej: What was the attitude towards the research and study of media and communication, public opinion and journalism within the former School of Political Sciences? Was there any resistance?

Bogdan: There was no resistance within the faculty. We were all learning together, students and professors alike. This was something new for all of us and, as such, an even greater challenge. We would buy literature wherever we could, borrowing from each other. We were, after all, pioneers. Discussions were very constructive. It wasn't as if some were teaching and others were learning.

(Photo: Sašo Slaček Brlek)

Sašo: What were the key questions you were facing at the time?

Bogdan: We had to break ground for some of the basic concepts. I was giving lectures on the sociology of communication. During those lectures, I was trying to capture the role of communication processes in social events and bring it closer to what was happening in our reality. In doing so, I came across the question of public opinion as one of the main results of communication. Our efforts were criticised by some, particularly by some Communist Party functionaries and authorities, arguing that we were introducing too American views on this issue. I tried to bring the Western European concept of public opinion closer to our reality and show that public opinion can be associated with self-management processes or, rather, that public opinion is even an essential element of self-management. They were telling me that public opinion did not exist here, that the function of public opinion was already being performed by social organisations, that the Socialist Alliance of the Working People was the intermediary institution between the decision-makers and the citizens, and so on.

The first books in the field of communication appeared at the time. There was Vreg's book about communication in self-management and there were some translations. We had more and more foreign literature available. Later, when I was a member of the Federal Parliament and participated in conferences abroad, I would always inquire what was new in the field of communications and public opinion. And that was the information we all gladly exchanged at that time. We were not shutting ourselves off, as I hear some at the faculty nowadays do.

But let me get back to the detailed study of the content and the sociological importance of communication, during which we were able to add our own findings to the conventional views coming from the West. For example, previously there had been much discussion about the basis of communication, the so-called line: who-what-to whom. We established, however, that it was particularly important who this "who" was from a broader environment. From which social environment does a person enter into this communication? And further: not only how communication arrives to someone, but also what are its consequences for the broader environment, so that the communication process actually becomes integrated into the social process. And this is how various discussions went on. In Ljubljana, we also organised round tables for colleagues from other republics, and so on.

Jernej: In the 1970s, Professor Vreg was criticised by the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Slovenia. How did you "defend" media and communication studies and Professor Vreg against the sanctions of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Slovenia?

Bogdan: That is a very difficult question for me. At some point, the Secretary of the Central Committee, France Šetinc, informed me that a special committee to discuss the professors at the school would be formed. When we were founding the faculty the basic question was whether journalism had its basis in some science or was it just a writing competence one acquired after he became a lawyer, a doctor or something similar, in short, after he had already obtained some other education. Even at the time of founding, some thought that this course of study was not necessary because journalism didn't have a scientific basis. It was considered just an ability to write that one had to acquire in addition to some other profession if one wanted to become a journalist. We were saying just the opposite - that research of communication and journalism was a special science, not just a writing skill. This was the basic dilemma and the main argument against establishing a specific journalistic faculty and the study of communication processes. This was the first and foremost problem at the school and later at the faculty.

Jernej: Even before the department of journalism was founded?

Bogdan: At the time when we were setting up the department. Other sciences were dealing with similar problems as well. There was also the question whether sociology was a science or not, and even a long time after there were faculties of sociology elsewhere, we didn't have a separate department of sociology. At the time, Jože Goričar was struggling for the recognition of sociology. It took even longer to recognise media and communication as a science on such an important phenomenon as communication, especially during the information revolution and at the time of the invention of new means of communication and their ever larger impact on people's lives.

Jernej: And how was this then linked to the sanctions against Professor Vreg?

Bogdan: Sanctions weren't directed only against Professor Vreg but against several professors. The Secretary of the Central Committee, France Šetinc, who even graduated under my supervision with a thesis on freedom of information, informed me that some sanction against Professor Vreg was being prepared, and told me: "You can help by becoming a member of this commission, so you can advocate your position and defend it". Journalism as such was in danger and the abolition of the study of journalism study was imminent.

Jernej: The department as a whole?

Bogdan: Closing the department and, of course, removing Vreg as the main pioneer of the study of communication. I participated in that rather unpleasant company so I could advocate the importance of this field of study and Vreg's positive contribution. I think three professors were expelled from the faculty at the time, but Vreg was spared. He only received a warning not to introduce too much American influence into the study of communication.

Jernej: Another key question at the time was the one we already posed at the beginning, namely whether there was any sense in journalism being a fundamental discipline?

Bogdan: It was the last time we had to defend the position that journalism had a basis to become a scientific study, and it was on that position that the Department of Journalism was based.

Sašo: In the 1950s you were actively engaged with media legislation. Can you describe how this work was done and what were the key challenges?

Bogdan: As the Secretary of Information I immediately felt the need to break new ground in this area, especially regarding the issue of freedom of communication. The issue of freedom of information, particularly with regard to newspapers, had been discussed by the United Nations since their beginnings. The first year after the end of the war they organised a conference on freedom of information, but it wasn't successful because representatives of the socialist countries and Western capitalism failed to reach an agreement. I felt that there was too much bureaucratic interference in the area of information in Yugoslavia. That some newspapers were abolished or individual contributions or even authors denounced. Because of that, I made some determined attempts to find solutions that would be at the level of advanced European countries. Comrade Marija Vilfan, who was President of the National Commission for UNESCO in Belgrade, helped me at the time. When I was involved in the reform of education, we sent a lot of teachers to other countries at UNESCO's expense so they could get acquainted with their school systems. At the time, Marija supplied me with a lot of literature, constitutional arrangements, laws of other countries, and the results of UNESCO's efforts for decisive solutions in this field. In cooperation with journalists from all republics, especially from Slovenia, and after taking into consideration all the variants used in different countries, especially those with the most advanced press and communication systems, I managed to finish the Law on Freedom of the Press and Other Means of Information.

It even contained some solutions that were more advanced than the ones we have today. The issue of reply, for instance. On one hand, the right of reply is something very important. It is a right that everyone whose honour or reputation has been tarnished or who has suffered economic damage should have. On the other hand, the media must be protected as well so that this right is not exploited to fill their pages with contributions of individuals who want to push their way into the content. We achieved that by granting the right of reply to published content to those whose reputation had been tarnished or who had suffered economic damage, and by making it obligatory for the publisher (the newspaper) to publish such a reply. If this is not done within a certain time limit, the case moves to court. Our solution was quoted even in the documents of the United Nations.

The Secretariat for Information was also a direct producer of important publications. We were the publisher of Mednarodna politika [International Politics] and Jugoslavija [Yugoslavia], which was a special representative magazine, as well as a newspaper that was lexicographically edited to complement the lexical data about Yugoslavia, and so on. We also published a magazine on topical issues of socialism in French. After 1961, Socialistična misel in praksa [Socialist Thought and Practice] was being published in English and French, and was intended for an international audience. We were trying to be intellectually active in the international area so that we could point out that, apart from the Soviet, there were also other models of socialism.

We also established some international contacts. Among other things, I was a member of the international committee in support of the Algerian revolution and sent a team of Belgrade cameramen to Algiers to film the Algerian fighters. That was the first documentary film about the Algerian revolution.

Let me also mention the cultural sphere. I was convinced that the best international propaganda for a country was its literature, its fiction. I managed to convince the parliament to approve a campaign in which ten works of fiction from all parts of Yugoslavia got translated into English and published by an English publishing house. Thus, for example, a few years later Ivo Andrić received a Nobel Prize for his most famous work Most na Drini (The Bridge on the Drina). By then, the English version of his book had already been available all over the world.

Working with information at this Secretariat allowed me to take an in-depth approach to the issues mentioned. I started attending lectures at the Faculty in Ljubljana and at the School of Political Sciences in Belgrade. When my mandate ended, I temporarily took over the editing of the Komunist [Communist] newspaper, which I tried to change into some sort of a normal social newsletter. Above all, I achieved that its production became decentralised. Previously, it had been published in Belgrade only, and there translated into Slovenian, Croatian and Macedonian. After decentralisation, everything was transferred to the editorial offices of the individual republics, which not only published material from the central editorial office, but were also allowed to complement the newspaper with happenings in their own republic. Some even accused me of trying to republicanise the Communist Party, but it was complete nonsense to print the newspaper in, say, Italian, in Belgrade. And I was striving for the same arrangement in the operation of the television broadcaster: we moved TV shows in Italian to Koper and even contributed 50 percent of funding to set up the Koper studio and begin its expansion to Italy.

Jernej: Who else in Yugoslavia was theoretically researching communication at the time?

Bogdan: That was mostly done in Ljubljana.

Jernej: Professor France Vreg and you?

Bogdan: Vreg was the central figure. His first book was some sort of a starting point in this field. However, it was also very important that we opened up to other faculties. We had a bilateral agreement with the faculty in Munich. Dallas Smythe was teaching at our Department of Journalism as a visiting professor for one year. Ever since my work for the radio, I had also been interested in international communication. From Belgrade, where I was still working at the time, I managed to convince the faculty in Ljubljana to opt for the programme of a symposium on the theme of communication and international understanding. Funding came from Belgrade, but the content preparation took place mostly here in Ljubljana. Here we would meet and discuss the content. Of course, we also informed UNESCO and asked for their patronage. The Vice-President of UNESCO was selected as the patron and they promised he would attend this symposium. That was the reason we invited even more people. We searched foreign literature for experts or universities that were particularly active in this field and then sent invitations to distinguished professors of journalism and communication in the United States, other countries and, in line with the policy of non-alignment, to countries such as India and Egypt. One of the main contributors was Ambassador Mustapha Masmoudi, who was the representative of Tunisia to UNESCO and supported our operations from there. The turnout was very high. I think there were about 120 participants from foreign countries alone.

The symposium started on 1 September 1968 - on the same day, the Soviet Union occupied Czechoslovakia. The session was somewhat out of focus because our friends from other countries were wondering what would happen next. In Yugoslavia, some were even saying that after Czechoslovakia it would be Yugoslavia's turn.

I argued that it was necessary to conclude this symposium with an urgent appeal for peace, and against incitement to international hatred or threat of war. People were telling us that the Soviet Union was spreading the rumour that they were actually defending Czechoslovakia against a new German aggression. I hoped we would be able to adopt a resolution on avoiding incitement to war and threat of war at all times in international relations. That did not happen because some of the non-aligned countries that received a lot of Soviet help, including military assistance, weren't willing to sign something like that.

Jernej: What about IAMCR, the International Association for Media and Communication Research? You were also a part of it. Were you active from the beginning?

Bogdan: When I started working at the Secretariat for Information, Yugoslavia had already been a member of that organisation. This organisation was interesting not only because it dealt with communication, but also because it had members of both blocs as well as the non-aligned. Members of this organisation came from Moscow as well. The organisation was in financial difficulty and under pressure to align itself with one of the blocs. But I wanted to support the openness of the organisation, and we managed to arrange a conference in Herceg Novi, which we also financed. We started the conference off with a paper on communication in the self-management system, to show off a little. Later, I was elected Vice-President of IAMCR and we carried out a conference in Switzerland and one in Pamplona in Spain. The organisation was very important for developing contacts and communication with experts and scholars all over the world.

Jernej: Was the 1968 symposium in Ljubljana a turning point at which communication became a major question for the Non-Aligned Movement?

Bogdan: Shortly after the symposium, in October 1968, there was the UNESCO General Conference in Paris. At each General Conference, the issue of culture and communication was on the agenda. Marija Vilfan invited me into the international delegation of Yugoslavia and I gladly joined because I knew I would meet new colleagues and gather new materials. And that indeed happened.

After talking with some of the participants, I felt that there was a lot more interest in communication issues in the organisation than seemed at first glance. When it came to information, the Congress leadership's only agenda item was the spread of a publication on UNESCO. During the discussion, however, I introduced the idea that UNESCO should act in a broader context and tackle the phenomenon of communication as a new social phenomenon that affects the lives of millions of people and also the relations between nations, and that there should be a scientific approach to the study of this new phenomenon. The idea was immediately supported by participants both from Canada and India. In a way, it was also adopted by the leadership of UNESCO. The Assistant Director-General, referring to the work of our section for information at the congress, also praised the Ljubljana Symposium and the idea that the study of communications required scientific devotion. Thus, it was concluded that UNESCO would organise an initial consultation of journalists, theorists, professors of journalism and others to form a programme on this issue.

The following year there really was such a consultation in Canada. I was not able to attend it as in those days my father was on his deathbed. After so much suffering (he had lung cancer) I had to stay with him to the end, so I excused my absence and asked for the resulting materials. The result of the consultation was a conclusion that UNESCO should organise a much broader scientific consultation on communication, and of course invite all the member states and all countries to join. This consultation in Canada had already sparked an idea that was also present at the next UNESCO General Conference where it was finally concluded that a Commission would be formed. It was named the MacBride Commission, after its president. It was assumed that Marshall McLuhan would be the leading force of the commission since he was one of the main and leading theorists of communication (which he called extensions of man), but because of health problems he could not participate. This commission met at the end of 1977 and in 1980 ended their work on this report. I prepared two papers for the Commission. One was a study on the new information order (what it would be like and what it would mean) that gave the Commission some basic orientation. The other was a paper on professional ethics in communication.

Sašo: The Non-Aligned Movement also addressed these questions. If I'm not mistaken, it was in 1973 at its Algiers conference that the Non-Aligned Movement first spoke out on communication issues.

Bogdan: Exactly.

Sašo: How did this happen?

Bogdan: The main initiator of this was Mustapha Masmoudi, who was the ambassador of Tunisia to UNESCO headquarters, but otherwise he was a participant of the economic conference of non-aligned nations in Algiers. It was in Algiers that the idea of reducing the economic gap between the non-aligned and the developed world was born. This encouraged him to present the proposal during the talks in Paris. I joined him immediately. I argued that the absolute dependence of certain countries on the information of the developed world had to be overcome since the non-aligned were appearing in the world media only when there was some natural disaster or a government was overthrown. It was necessary to develop the national media and so on. I immediately suggested that we work together and later I even prepared a study on the new information and communication order for the MacBride Commission where I argued that this issue should in fact be the central issue of our Commission.

Jernej: How were you appointed to this Commission? Did MacBride himself suggest any members?

Bogdan: Since I had contributed to some other UNESCO projects, I was probably put on the preliminary list by UNESCO and Yugoslavia was only asked for confirmation.

Jernej: Do you perhaps know how it was in the case of other countries?

Bogdan: You know what, I think the quality of work was the most important factor. The Indian member of the delegation, Boobli George Verghese, was the leader of the Indian national commission which dealt with the question of how communications should be organised in very difficult conditions, since so many different states needed to be united. There was also Hubert Beuve-Mery, the founder of Le monde, the French newspaper, Mustapha Masmoudi, Gamal El Oteifi from Egypt and, of course, Gabriel García Márquez from Columbia. Márquez was invited not only as a writer but also as a publicist, and he was extremely friendly.

At my initiative, one of the MacBride Commission's sessions was held in Dubrovnik. Márquez fell in love with Yugoslavia when he was in Dubrovnik. He visited a barber's shop and, while chatting with the barber, he mentioned the country he was from, and the barber said: "I've just finished reading a great book by some author. One Hundred Years of Solitude or something like that". And Márquez exclaimed: "Well that's me!". The fact that he was recognised in a foreign country in this manner made him communicate with me even more.

Sašo: In our recent interview, Breda Pavlič[3] mentioned that Yugoslav politicians were not favourably disposed towards the study communication issues, that there was quite some resistance.

Bogdan: Well, you know, their opinion was that information is primarily a tool of power. Everything we were doing, researching public opinion and so on, meant removing their monopoly in a way. They were against my commitment to public opinion, as well as against other measures that led to the democratisation of this area. And the intention really was to democratise the sphere of communication and to democratise the system.

Sašo: What was the view on the social role of journalism?

Bogdan: The official position on the role of journalists was that a journalist is a socio-political worker and must carry out the mission of social organisations. When we gave up on that and gave freedom to journalists, it was a big move. At the congress in Novi Sad, Manca Košir and I defended the position that journalists cannot be burdened with the role of a socio-political worker because then they would basically have to represent the interests of social organisations. Up to this congress, journalists were seen as socio-political workers who were responsible for the social situation, rather than free commentators reporting about this situation. This position was changed at the Yugoslav Congress of Journalists in Novi Sad back in the 1980s.

Sašo: So there was no considerable support from politicians when you were addressing the issue of the democratisation of communication at UNESCO?

Bogdan: I never had much chance to tell the Yugoslav public what we were doing in Paris in that Commission. The Soviet representatives were especially problematic. At the first meeting of the Commission, one of the prominent members of the Central Committee addressed the American representative and said: "Of course, our task is to find faster, more efficient forms of communication. Our agency, TASS, for example, needs so many bytes for a piece of information, in Paris they need so many. In Paris, they need this much time to publish the information, we publish it in this much time".

Jernej: So a purely technical approach.

Bogdan: Purely technical. I said this: "I believe we haven't come here as engineers, but rather as social scientists, therefore we must treat information as a social phenomenon. Information in the service of man. This is what the new economic order and the new information and communication order should lead to". This was the first time the Soviet representative jumped on me and said: "What order? This sounds like Hitler's order to me". And I replied: "You're going to talk to me about Hitler's order in connection with Yugoslavia? You know well enough what our contribution to the fight was". And this conflict apparently intrigued the Western press well enough that they started paying more attention to our Commission. Also, there was no more fear that his was something one-sided, something in the political domain of communism.

The Soviet Union on the other hand soon realised that it would indeed be foolish to be against it. This man was recalled from the Commission and they sent another member of the Commission, Sergei Losev, the director of the TASS news agency. All of a sudden, people in other countries under the Soviet influence started to support the new order. They were saying countries would be given more power and that this field would be better controlled. And at the end that actually became the main problem.

In the West they started turning against us, saying that we were talking so much about how countries should support the construction of new communication systems, radio stations and so on. They argued this would lead to the nationalisation of communication activities.

Jernej: So, first you had major difficulties with the Soviet Union, and then with the Americans?

Bogdan: Exactly. Especially after the MacBride Report was published just before the 1980 UNESCO General Conference in Belgrade. In the preface, MacBride even thanked Masmoudi and I for having influenced the direction the Commission took. And of course I had a feeling that we must prepare well for the conference so they would not refute our report and with it the very idea of a new information and communication order.

I even made some extra effort and wrote a brochure in Slovenian. During the preparations, I managed to convince the Secretariat for Information in Belgrade to finance my book in foreign languages so before the conference my book on the new order had been published in English, French and Spanish. Later, I learned from some of my colleagues that it had been warmly received, especially in South America, because the question of increased independence from the US monopolies that were controlling their communication world was particularly pertinent to them.

Sašo: The MacBride Commission Report is quite radical in some parts, criticising the doctrine of the free flow of information, speaking about economic censorship and that economic censorship can be as dangerous as the bureaucratic one. You were probably expecting that the United States would react strongly to it.

Bogdan: The first chance was at the UNESCO Conference and the non-aligned countries elected me as president of the Committee on Information. I led the Committee in such a way that it confirmed the MacBride Commission Report and the requests for a new communication order as well. Thus, when the voting took place, only the English delegation expressed some restraint, but did not vote against it. The Americans even confirmed it. Nonetheless, the American representative came to me after the conference and asked whether the public could be informed in such a way that it would seem they were against the new order as well. I replied: "I'm sorry, it has already been published (laughter) and nothing can be done now". The first test was thus successfully passed.

Sašo: However, the West later intensified its resistance. In 1984, the USA withdrew from UNESCO in protest, followed by the UK the next year as a sign of protest against the new international information and communication order...

Bogdan: At the time, I wrote an article entitled It is not only about communications. The English and the Americans were annoyed by the fact that every meeting of the United Nations and other international forums were attended by so many representatives of the non-aligned countries. They wanted to show the non-aligned countries, which already had the majority in these global organisations, that they could not play around with this majority. The first measure against UNESCO was in fact only the beginning of a sharp international course the Americans then chose.

Jernej: If the American leadership were different, they probably wouldn't have reacted like that. Jimmy Carter, for example, was more moderate with regard to American actions in international relations.

Bogdan: No, I think that this is not a matter of one man, but rather of the entire American international political direction that was changing. Above all, I think I can hold the position I then wrote down - that it was not just about communication, but also about general relations in the international arena.

Jernej: How would you assess the work of the MacBride Commission today?

Bogdan: We conducted a round table about the MacBride Commission Report that was arranged by the European Institute for Communication and Culture and chaired by Slavko Splichal. It was interesting. The title of the consultation was "25 Years Later". I prepared the introductory article[4] in which I talked about what, in my opinion, survived from our work and our report. Also about all the major changes in the world of communication. And that was also my final act in this field.