Anti-Neoliberal Neoliberalism: Post-Socialism and Bulgaria's "Ataka" Party

Department of Communication, University of Pittsburgh, USA, mym7@pitt.edu

Abstract: The last elections (2014) for European Union deputies once again confirmed the popularity of far-right parties. Despite scholarly attention, racism and xenophobia in the easternmost part of the EU, remain relatively unexplored. This essay focuses on Ataka, the first far-right political party to enter Bulgaria’s parliament after 1989. Specifically, the article focuses on its official media discourse in order to explain its complex position on neoliberalism. While this party engages in criticisms of neoliberalism, its understanding of it is non-economic and ambiguous. A rhetorical analysis of the party’s newspaper reveals that angry attitudes towards neoliberal economics fuel movements such as Ataka. However, Ataka often presents neoliberalism as a cultural project focused on multiculturalism, “Islamization”, and anti-nationalism. The essay explores this strategy to fuse economic demands with issues of identity. As such, this piece calls for a more nuanced understanding not only of the discourse of contemporary far-right movements, but also of neoliberalism itself.

Keywords: Far-Right, Neoliberalism, Post-Socialism, Ataka, Bulgaria

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my adviser Dr. Brent Malin, as well as Georgi Medarov and the members of social center Xaspel in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Date of Acceptance: October 14, 2015; Date of Publication: July 20, 2015.

1. Introduction

The fight against illegal immigration, which turned entire

states such as

California, Florida, Arizona and others, into the

property of people of color and

even transformed them into

Muslim regions, proves to be unsuccessful for now.

A

paradigm

of this is the now the entirely Muslim city of Dearborn,

Michigan. The

attempts of some states, such as Arizona, to

criminalize illegal immigration and to

extradite immigrants,

clashes with the neoliberal philosophy of the ruling

Democratic Party (Washington Closes 2011, 2).

On May 20th 2011, Muslims gathered for prayers in front of Banya Bashi mosque in downtown Sofia, the capital of the EU’s poorest member—Bulgaria. The mosque, built in 1576, is located in the “triangle of tolerance”, which also includes the St. Nedelya Orthodox Church and the Sofia Synagogue. During the worship, approximately two hundred activists of the far-right party Ataka (“Attack” in English), wearing black shirts and touting a Bulgarian flag, interrupted the prayer. They shouted obscenities, pelted the Muslims with eggs, and initiated a fight. Despite police intervention, several worshipers lay bloodied as prayer mats burned nearby. The President of Bulgaria, Georgi Parvanov declared the violence, a “provocation unknown in the new Bulgarian history” (Bulgaria Shocked 2011).

In 2005, Ataka won 9% of the parliamentary vote and in 2006 its leader and founder, Volen Siderov,[1] reached a run-off for the presidency where he achieved 24%. In 2007, the year Bulgaria entered the EU, Ataka gained 14% in the historic first elections for European Deputies. In the parliamentary elections of 2009, Ataka gained 9.36% and for the larger part of the term supported the ruling conservative party Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (CEDB) (Central Electoral Commission). After a lackluster performance in the 2011 presidential elections and a crisis within the party, many predicted the end of Ataka. However, riding the tide of mass protests over the high price of electricity, Ataka proved resilient gaining 7.3% of the votes in the May 2013 snap elections. Thus it seems that the project Ataka inaugurated nine years ago will continue to play an important role in Bulgarian politics. This raises the question of what discursive strategies help reactionary parties, such as Ataka, to perform well in supposedly more multicultural post-1989 Europe.

This essay sheds light on the issue through an analysis of Ataka’s discourse on neoliberalism. The next two sections of the article provide a brief background to one of the central debates in the extensive scholarship on the far-right in Europe and situate Bulgaria’s Ataka within this discussion. Here the essay advances the argument that the economic and socio-cultural effects of neoliberal economics coupled with the fading away of the differences between traditional political parties created an environment fertile for the emergence of Bulgaria’s first post-1989 parliamentary represented far-right party. The rest of the paper engages in an in-depth analysis of Ataka’s discourse on neoliberalism in its official daily newspaper also called Ataka. Framed primarily in Ernesto Laclau’s rhetorical theory of populism the essay explains the functioning of Ataka’s complex (mis)understanding of neoliberalism. Because it both reinforces a range of neoliberal ideologies and offers a variety of supposed critiques of the neoliberal project, Ataka provides an important case for exploring the subtleties that underlie a multifaceted rhetoric of neoliberalism.

2. The Far-Right East and West

In the last thirty years, the European far-right has been stronger than any time since 1945 (Mudde 2011, 7). Its popularity has attracted significant scholarship and the books on it “might already outnumber the combined total of books on all other party families together” (Mudde 2007, 2). However, this research mostly focuses on Western Europe, leaving “a notable lack of reliable information on racist extremism” in Eastern Europe (Mudde 2006, 247). For this reason a brief comparison between Ataka and its counterparts across Europe is in order.

One of the most slippery yet most highly emphasized features of these movements is their “Euroskepticism.” Rather than being “anti-European”[2] these parties fantasize a pan-European paradigm that they see as more “Christian”, “traditional”, and heterosexual than the Europe against which they fight. Thus even though these parties focus primarily on their local context, they also advance a vision of Europe as a whole. Ataka is not an exception as it claims to be the local equivalent of the far-right parties in Western Europe. Once Ataka gained prominence Volen Siderov declared that the party “became part of the European nationalist space and legitimized itself as a European party” (Siderov 2007, 331). As such, and as in so many discourses in Bulgaria, Ataka’s nationalistic rhetoric ironically suffers from the inferiority complex of an Eastern European and Balkan subject that vows for the attention of its more “advanced” Western European brother, in this case the far-right parties of the West (see section 4.5).

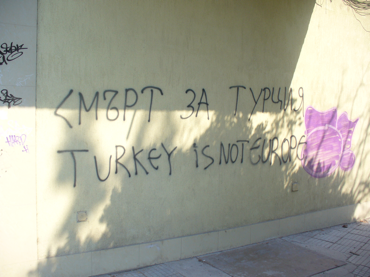

Figure 1: “Death to Turkey” and “Turkey is Not Europe.” Graffiti in Pernik, Bulgaria 2012.

Perhaps one of the most common features of the far-right in Western Europe is their Islamophobia.[3] Ataka follows the trend and even regards itself as the bulwark of the EU and its easternmost frontier (see section 4.4). This choice is further reinforced by history. The historian Maria Todorova argues that the Balkans are an Ottoman legacy. Since gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire (in 1878 in the case of Bulgaria), the Balkan countries sought to relinquish every claim of Ottomanness and saw Turkey as the heir of the Ottoman Empire. For this reason Balkan nationalism is firmly embedded in the anti-Muslim sentiment that has led to the continuous eradication of ethnic multiplicity in the region. According to Todorova this institutionalization of ethnically homogenous bodies signals the “final Europeanization of the region, and the end of the historic Balkans and the Ottoman legacy” (Todorova 2009, 199). In this way, Ataka and other such parties are ideal carriers of this “Europeanizing” project now intensified by the growing Islamophobia in the West.

Still, it is worth noting a difference between Ataka and the far-right parties across Europe. The working-class profile of populist right-wing parties has been the focus of a number of studies (for example Oesch 2008; Kalb and Hamlai 2011). But this process of “proletarianization” of the extreme right precipitated by the transition to postindustrial society, is not as pronounced in Bulgaria. One of the first field studies of Ataka’s voters concluded that they differ from the “classical” Western model of working-class voters who support the far-right. The study found that “the electoral profile of Ataka is very unexpected” with “the majority of people relatively educated, relatively well-off and employed” and claimed that members of all groups including those with “university education, businessmen, young people, pensioners and the unemployed” voted for Siderov during the presidential elections in 2006 (Ivanova 2007, 5). Hence the study showed that there were significant deviations of the standard story that “the losers of transition” vote for Ataka.[4] As I discuss below, Ataka’s resistance to being seen as a “working-class” party is also reflected in its media discourse.

3. Ataka and Post-Socialist Neoliberalism

The literature on the economic ideology of the far-right in Eastern Europe is divided. According to Cas Mudde (2007, 122) some scholars stress on these parties’ alleged neoliberal economic program while others argue that they “campaign strongly on social issues and around key concepts such as social justice.” Indeed, according to Mudde (2007, 122), “the Bulgarian Ataka presents its preferred economic model as ‘social capitalism.’” Other Western academics have also defined Ataka as economically left-leaning because it “plays up ethnic and religious intolerance to garner far-right support for its far-left agenda” (Ghodsee 2008, 26). In Bulgarian political discourse many commentators view Ataka as economically “ultra-leftist” as well (Todorov 2007, 81).

The quandary over Ataka’s economic discourse is the entry point of this article. How does this far-right party maneuver its discourse on identity and economics within the political landscape of one of the most neoliberalized economies in Europe? Ultimately, I argue that the social anger produced by neoliberal economics fertilizes movements such as Ataka. However, while Ataka takes advantage of the disillusionment with what it calls “market fundamentalism” (until recently Ataka was the only political party in Bulgaria to use the term “neoliberalism”) and mimics leftist arguments, in the speeches of its leader and the discourse of its official newspaper, its anti-neoliberal rhetoric frequently departs from classical left-wing narratives. In fact, in this discourse neoliberalism is not only highly ambiguous but it also figures as a noneconomic project. Although, Ataka occasionally interprets neoliberalism as an economic doctrine that impoverishes the majority while enriching a minority, this type of economic argument frequently succumbs to a cultural understanding of neoliberalism not as an economic phenomenon but as a cultural and globalist project focused on multiculturalism, “Islamization”, minority rights and anti-nationalism. This view of neoliberalism permits a rhetorical fusion of issues of identity and economics that converts minorities and neighboring countries into economic oppressors. The second part of this essay reveals the concrete dynamics of this fusion in Ataka’s official print media.

But Ataka’s noneconomic reading of neoliberalism should not be viewed only as an advantageous misrepresentation. Neoliberal economics causes turmoil in the economic sphere but it also destabilizes the socio-cultural milieu. The contemporary unsettling of traditional notions such as territory, nation, and citizenship aids movements such as Ataka in articulating social anger in cultural terms. However, their deflection of anger from harmful economic policies to issues of national identity, immigration, and minority rights ends up reinforcing neoliberalism rather than challenging it, since historically neoliberal discourse strives to transfer its guilt for its economic deficiencies to personal and cultural failures.

The interaction between economic collapse and the broader effects of neoliberalism necessitates a more nuanced understanding not only of the discourse of Ataka, but also of neoliberalism itself.

3.1. The Effects of Neoliberal Economics in Bulgaria

In order to understand Ataka’s framing of neoliberalism, first it is important to explore the deteriorating economic conditions of Bulgaria. However, the effects of neoliberal policies on the country are so extensive and far-reaching that it is next to impossible to describe them here. Nevertheless, several facts provide a basic idea of the profound transformation of the Bulgarian state after 1989.

David Harvey (2010) defines neoliberalism as “a class project” that “legitimized draconian policies designed to restore and consolidate capitalist class power” (10). Under this definition post-socialist Bulgaria is a paradigm of the neoliberal state. It has the lowest flat income tax (10%) in the EU and globally (Mitchell 2008, 5) as well as the lowest corporate tax (10%) in Europe (Phillips 2010). The radically conservative overhaul of the tax code prompted the “Heritage Foundation” to rank Bulgaria thirteenth in the world in “fiscal freedom” (Heritage Foundation 2014).

However, mass privatization, shock therapy and other reforms failed to improve the social conditions and on virtually every living standard indicator Bulgarians are worse off than they were in 1989 (Vassilev 2011). The country ranked 26th on the UN Human Development Index (HDI) in 1990, but by 2012 it slipped to 57th position (United Nations 2013). One of the outcomes of the dramatic decline in the quality of life is a severe demographic collapse. In 1990 Bulgaria had nine million citizens, compared to only 7.3 million today (National Statistical Institute 2011, 3).

Figure 2: A makeshift monument to a protestor who self-immolated in Varna, Bulgaria 2013.

In February 2013, the discontent over Bulgaria’s experience with capitalism erupted. In what were deemed the biggest protests since 1989, Bulgarian citizens angered by the unbearable price of electricity marched across every major city. The center-right government resigned, but the protests continued unabated and even took a highly disturbing turn. Seven Bulgarians burned themselves alive in public, six of them fatally, in protest at the worsening poverty levels (Esslemont 2013). Ataka took advantage of the unrest and called for the nationalization of the electric companies. Without a doubt this helped it to remain in parliament following the snap elections of 2013.

Post-Socialist Neoliberalism and the Politics of Consensus

In sum, in order to understand the success of Ataka, it is necessary to begin at the level of the disastrous outcomes of neoliberal economics. Neoliberalism generates sharp social contradictions that cannot be contained within the consensual framework of contemporary liberal democracy. One of the reasons why far-right parties take advantage of economic discontent is the fact that formerly leftist parties now embrace free market policies. It is the far-right that fills the vacuum left by the fading of traditional, European, leftist politics while monopolizing and rearticulating the circuit through which economic anxieties are expressed. The denigration of terms such as “worker”, “class”, and “equality” by the pervasive anticommunist discourse in Eastern Europe has made things there even worse. In his study on the transformation of the famous Polish labor union Solidarity from a democratic inclusive organization to a post-socialist far-right movement that sought to ban abortion and add a clause in the Polish Constitution that praises God and Catholicism, David Ost (2005, 181) argues that “everywhere we look [across Eastern Europe], we have had labor crippled by neoliberal reforms and new elites anxious to stifle labor discontent, leading to weak trade unions, low class sensibilities, and burgeoning class anger looking for ways to express itself.” Thus he concludes that “the weakness of class cleavages has pushed political life in a decidedly illiberal direction, yielding a democracy in which socioeconomic conflicts have been mobilized around identities rather than interests, with others defined as aliens rather than opponents” (Ost 2005, 2). Ataka is yet another manifestation of this post-socialist environment.

Ataka’s zealous anti-establishment rhetoric disturbs the ideologically homogenous discursive space of Bulgaria’s neoliberal consensus. Indeed, Chantal Mouffe argues that the major factor that unites the radical right parties in Europe is precisely the consensual environment in which they emerge. “Their growth has always taken place in circumstances where the differences between the traditional democratic parties have become much less significant than before” (Mouffe 2005, 66). Ataka emerged in 2005 when all mainstream parties adopted technocratic language and policies which supported EU Accession, NATO membership, establishment of five US military bases in Bulgaria, support for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as economic liberalization. But the discursive strategies through which movements, such as Ataka, organize social anger against the status quo along cultural and identity cleavages remain to be explained.

In order to further explicate how economic demands and cultural claims interact in order to produce Ataka’s nuanced view of neoliberalism, the rest of this paper uses Ernesto Laclau’s rhetorical theory of populism to engage in a thorough analysis of the seventy-five paper issues of Ataka’s daily national newspaper from June 1 to August 31, 2011.[5] This period is significant because it encompassed the aftermath of Ataka’s controversial assault on the mosque in Sofia, as well as the mayoral and presidential electoral campaigns. Additionally, two important international events took place during this period: the English riots and Andres Brejvik’s terrorist attacks in Norway. A micro-level analysis of Ataka’s mediated rhetoric is essential to a movement of this kind because media is of a particular significance to anti-establishment parties, especially in their early stages of development (Ellinas 2010, 204). In fact Ataka emerged as a low cost, reactionary cable television show (also called Ataka) in 2003 and metamorphosed into a political party in 2005. Thus it comes as no surprise that some scholars have argued that Ataka’s “rise to prominence was largely aided by its skillfully crafted media blitz” (Ibroscheva and Raicheva-Stover 2009, 1). In fact, in 2011 Ataka became the first political party in Bulgaria with its own television network (Alfa).

Figure 3: A billboard advertising Ataka’s television network in Sofia, Bulgaria 2014.

In this way, Ataka channels a significant amount of its state subsidy into mediaperations.[6] There is a revolving door between the parliamentary group and the journalists of Ataka. Several of its MPs, including Siderov, are television hosts who combine their work in parliament with their television shows. Most, if not all, of the MPs contribute to the party newspaper of which Siderov is the editor. Additionally, Ataka uses and entertainment-style song and billboards to advertise its television network across Bulgaria. Siderov has also published five books.[7] Despite this media presence, however, Ataka does not underestimate classical persuasion. Without a doubt Siderov is one of the most charismatic and skillful orators in an otherwise dull Bulgarian parliament. Even more importantly, he is a regular speaker at every rally organized by Ataka, usually mounting improvised stages, such as the back of a truck, from which he speaks to the crowd with a loudspeaker. All of this makes Ataka the political party that takes words and persuasion most seriously in Bulgaria. This is a major reason why Laclau’s emphasis on rhetoric and his discursive theory of populism are of a particular use for this study.

Figure 4: Ataka’s leader Volen Siderov giving a speech in front of the European Commission in Sofia, Bulgaria in 2014.

Ataka’s Rhetoric

The rhetorical strategy through which the fusion of economic and cultural demands is articulated is of foremost importance to our understanding of a far-right populist party such as Ataka. However, studies of this kind are rare because of the negative connotation associated with “populism.” Ataka and other populist parties frequently change the enemy and contradict themselves as they continuously point to various causes of the socio-economic problems around them. This has contributed to a widespread and hasty dismissal of these movements as “opportunistic”, and “irrational”. But the instability and radical shifts engendered by neoliberalism also account for the conflicting trajectories of populist discourse. Thus another reason why Enesto Laclau’s theory contributes to this study lies precisely in his neutral and formalist approach to populism.

According to Laclau the ambiguous discourse of populist parties is not an aberration but a precondition for the construction of political meanings. He argues that “the language of a populist discourse—whether of Left or Right—is always going to be imprecise and fluctuating: not because of any cognitive failure, but because it tries to operate performatively within a social reality which is to a large extent heterogeneous and fluctuating” (Laclau 2007, 18). Laclau adds that under “global capitalism” social heterogeneity is amplified and this creates a more extended and difficult to reconcile chain of demands in which capitalism cannot be understood “as a purely economic reality”, but must be seen as “a complex in which economic, political, military, technological and other determinations—each endowed with its own logic and certain autonomy—enter into the determination of the movement of the whole” (Laclau 2007, 230). In addition to Laclau’s approach to the study of populism, his theoretical framework provides the tools and the scope necessary to analyze the complex discourse of a movement such as Ataka.

Ernesto Laclau identifies a social demand as the smallest unit in the constitution of a popular identity. A series of social demands coalesce in an “equivalential chain”—a diverse group of unsatisfied demands. The equivalential chain is instrumental in the establishment of an “internal frontier” that splits the political spectrum (unfulfilled social demands vs. unresponsive power) (Laclau 2007, 74). The chain has to transition from a mere bond of solidarity of unfulfilled demands to a stable system of signification in order to become the ground for popular identity. The moment of “thickening” and crystallization of the equivalential links is what constitutes “the people” of populism (Laclau 2007, 74). The subtlety is the rhetorical mode through which this is accomplished.

Laclau employs catachresis (a figural term which cannot be substituted by a literal one, i.e. the leg of a chair) to explain the construction of “the people.” He argues that through a hegemonic operation (“a particularity taking up an incommensurable universal signification”) one particular social demand acquires a certain centrality: “its own particularity comes to signify something quite different from itself: the total chain of equivalential demands” (Laclau 2007, 95). Hence, the “market” in the 1989 Eastern European context meant much more than an economic arrangement because it embraced diverse popular demands such as “the end of bureaucratic rule, civil freedoms, catching up with the West, etc” (Laclau 2007, 95).

Ataka, exhibits a long and heterogeneous equivalential chain that encompasses a variety of demands. This is why Ataka appears as a “something-for-everyone party” (Ghodsee 2008, 37). Nationalism, and the phrase that serves as a closure of every speech of Volen Siderov, “Bulgaria above all, Bulgaria for the Bulgarians”, plays the catachrestical function theorized by Laclau. It serves as an empty signifier that plays the role of a totality encompassing a diverse equivalential chain. This political logic allows Ataka to attract support from an economically diverse group of people.

However, this political logic is vulnerable because of constant tensions at the level of the equvalential chain. The particular demands are “split between the particularism of their own demands and their popular signification imparted by their inscription within the chain” (Laclau 2007, 95). Hence, the weaker the demand is, the more it depends on the popular inscription. (Laclau 2007, 95).

The analysis of the seventy-five issues of Ataka’s newspaper indicates that the demands framed only in economic terms are rarer and weaker components within the party’s chain of demands. But when these demands are not subsumed by the party’s hegemonic framing of economic issues along ethnic and cultural lines, their expression provides a unique criticism of capitalism almost completely absent from the Bulgarian public sphere in the last twenty-five years. While I list some of these unique criticisms in the next subsection it is important to note within this discussion of Laclau’s theory of populism that Ataka is not just a populist movement but a right-wing populist movement. The current conjuncture in the Balkans and Europe, in addition to the developments in Latin America in the last fifteen years, highlight the reasons why one should be cautious with the flexibility, neutrality and formalism of Laclau’s framework.

Mainstream liberal scholars and commentators have overlooked the difference between right-wing and left-wing populism.[8] The main difference between the two is the reductive and exclusionary meaning of “the people” of the right and the generally inclusive and broad meaning of the term on the left. For this reason, in a recent piece on the leftist Greek party SYRIZA, Yannis Stavrakakis and Giorgos Katsambekis (2014) criticize the subsuming of SYRIZA and the Golden Dawn (the Neo-Nazi party in the Greek parliament) under the same banner of “populism.”

It is clear that in the context of SYRIZA’s discourse, ‘the people’ is called upon to participate actively in a common project for radical democratic change, a project of self-fulfillment and emancipation. As we have also seen, unlike the ‘people’ of the extreme right, the ‘people’ of the left is presented as a plural, inclusive and active subject unbound by ethnic, racial, sexual, gender or other restrictions; a subject envisaged as acting on initiative and directly intervening in common matters, a subject that does not wait to be led or saved by anyone (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis 2014, 135).

In this essay I argue that despite its criticisms of neoliberalism Ataka advances a right-wing exclusionary populism because it targets primarily the Roma (section 4.3) and Muslim minorities and Islam in general (section 4.4), while its criticism of capitalism remains very ambiguous (section 4.4) and it narrowly identifies itself with the Western European far-right (section 4.5). But firstly, in the next section I highlight the ways in which Ataka mimics leftist arguments.

Economic Anti-Neoliberalism

Anti-capitalist rhetoric engendered by the post-socialist economic failures in Bulgaria appears on the pages of Ataka. It claims that “we live in raw capitalism from the era of Emil Zola” to which Ataka responds with a “socially oriented policy” (Tasheva 2011c, 8–9). It attributes poverty and depopulation to the “neoliberal dogma of ‘privatization, liberalization, and elimination of statehood’, most commonly known as the ‘Washington Consensus’” (Tasheva 2011a, 4–5). This rhetoric portrays neoliberalism as “the only form of governance that provides the power wielding caste with an opportunity for a scot-free robbery” and “turns the state into a defense mechanism for 2–3 percent of the population while it steals from the remaining 98 percent” (Tasheva 2011a, 5).

The leader of Ataka, Siderov, calls for a “change to the colonial model of governance of Bulgaria” (Ataka’s Gathering 2011, 1). According to him, Bulgaria exists in “a non-sovereign, anti-national framework, which eliminated us as a state with its own economy and foreign policy” and as a result:

We are melting rapidly into a twenty-year-old economic, social, and spiritual destruction, of mass impoverishment, two-digit inflation and unemployment, collapsed healthcare and high mortality rate, growing emigration and draining of the intellectual potential, absent a national strategy for coming out of the swamp [...] Wild, cave-era capitalism sent to hell the illusions for democracy and directed the national wealth into the pockets of a few “god-chosen” individuals and their partners in the underground world (Siderov 2011c, 7).

With this rhetoric, Ataka not only taps into widespread economic grievances, but also takes advantage of the socialist party move to the right. This is a phenomenon not unique to Bulgaria. Laclau argues that in France, after the collapse of communism, the differences between the Left and Right faded away but the need for a radical vote of protest remained. As a result, the ontological need to express social division became stronger than its traditional attachment to the Left. This led to the move of former Communists to the National Front. Laclau concludes that, “today’s resurgence of right-wing populism in Western Europe can largely be explained along similar lines” (Laclau 2007, 88).

In Bulgaria during the 1990s the “anti-communist” versus “former communists” dichotomy similarly diminished. After 1997 the Bulgarian Socialist [former Communist] Party (BSP) “came to advocate a truly social-democratic platform and to support a pro-EU and pro-NATO foreign policy” (Spirova 2008, 482). Its implementation of the highly regressive flat tax in 2007 as well as the permission of five US military bases on Bulgarian territory disenchanted many of its supporters.[9] Ataka fills this gap by being one of the strongest critics of Bulgaria’s involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan and the decision to host US bases. It is also one of the major forces that opposes the flat tax imposed by the “right-wing extremism” of the “absolutely rightist” socialist party and describes Bulgaria’s tax system as one of a “colony” (Our Tax System 2011, 8). It portrays the flat tax as a social experiment advanced by US economists who impose the “libertarian ideas of the World Bank and the IMF” on every country in “New Europe” but not on countries in the West (Our Tax System 2011, 9).

Additionally, Ataka criticizes privatization and denounces the neglect of local agriculture. It concludes that despite the “enormous stupidities” of the former regime, such as forced land collectivization, Bulgaria was a leader in agricultural production. However, the multinational supermarket chains destroyed Bulgaria’s self-subsistence after 1989 (Noev 2011, 8). As a result, the Bulgarian entrepreneur lost while the once self-subsistent country entered the paradoxical situation of importing tomatoes from Jordan, a desert country, and apples from distant New Zealand (Siderov 2011a, 6).

Ataka echoes environmental groups’ concerns as well. It opposes Chevron’s proposal to explore shale gas reserves in Bulgaria’s fertile region of Dobrudzha and highlights the detrimental effects of hydraulic fracking (Tasheva 2011b, 4). It even invokes Joshua Fox’s documentary Gasland to advance its argument. Similarly it resists gold mining projects of the Canadian company “Dundee Precious Metals” in Bulgaria’s Rhodopa Mountains because “multinational corporations bestow little else for the Bulgarian state then environmental destruction” (Dundee Steals 2011, 4).

In sum, demographic and socio-economic degradation provoked a legitimate radical voice and Ataka’s aggressive discourse turned into an outlet for post-socialist grievances. This phenomenon, common across Europe, prompts Chantal Mouffe to argue that “it is high time to realize that, to a great extent, the success of right-wing populist parties comes from the fact that they articulate, albeit in a very problematic way, real democratic demands, which are not taken into account by traditional parties” (Mouffe 2005, 71).

However, it is important to note that the rhetoric critical of the economic outcomes of neoliberalism is only one segment of Ataka’s populist discourse. The rest of this article demonstrates how its articulation of anger is far more ambiguous than a straightforward borrowing of the slogans of the weary Left. What is more, even when movements, such as Ataka, propose statist, redistributive economic policies they couch them in racial and xenophobic discourse that reinforces the inequalities they are purported to overcome.

Ambiguities on Neoliberal Economics

The seemingly anti-privatization rhetoric of movements such as Ataka also need not be hastily described as leftist. The role of the state envisioned by Ataka is not socialist. “We have objections to the colonial model of Bulgaria. It has to change—economics, services, successful sectors in Bulgaria have to be in Bulgarian hands—whether private, whether state, whether private-state or other forms, but they have to be Bulgarian and not foreign”, Siderov writes (Siderov 2011e, 12). In other words, Ataka proposes a corporatist type of capitalism that replaces class conflict with cooperation between workers and bosses in the name of national unity. In his books Siderov states this directly. He argues that, “the trap of global communism was class theory and its goal to pit groups of people from the same nation against each other” (Siderov 2011e, 93). Instead, according to Siderov, class struggle can easily be avoided because “the employer” and “the wage worker” and all the “different layers can work and coexist in harmony, if there is national thinking from top to bottom” (Siderov 2007, 287). Additionally, its rhetoric focuses narrowly on “strategic” sectors of the economy rather than on privatization as a whole.

Its view of consumerism is also vague. It claims that Bulgarian consumerist capitalism lacks the law and order of the West. It does not call for anti-consumerism but for a “return” to Bulgarian and Christian Orthodox values, which will make consumerism more “bearable” and beneficial in “moving us ahead” (Tomov 2011a, 12). Besides these types of arguments, Ataka’s cultural pages advertise Hollywood and Walt Disney products such as The Hangover, Kung Fu Panda, and Konan. In other words, despite its nationalistic and Orthodox rhetoric, Ataka is anxious to appear as a modern phenomenon that does not shy away from the West. But in this way it often ends up reflecting neoliberal values. This is evident in its electoral campaigns as well.

Ataka does not present itself as a workers’ party but appeals to market values. Thus, in the local elections of 2011, Ataka praised its candidate for mayor in Sofia as the 2008 “Entrepreneur of the Year in the Construction Business” (Ataka Liked 2011, 1). Similarly, it portrayed its candidate in the city of Gorna Oriahovitsa as a successful businessman and a “real employer” with “managerial experience” (Dineva 2011, 13). Its candidate in Stara Zagora was a young man who studied “Speech and Communication” in New York, where he learned effective fine collection and strict tax implementation (Antonova 2011c, 13). Thus it comes as no surprise that in the 2009 election for European deputies Ataka achieved its highest electoral result in one of the most affluent Bulgarian cities, the famous Black Sea resort of Primorsko (Antonova 2011a, 9).

In addition to their rhetoric, from 2009 to 2011 Ataka supported one of the most neoliberal parties to enter the Bulgarian parliament—CEDB. The Vice Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Simeon Dyankov, duly enforced its vision of economy “free to the minimum of state intervention” (Dinkov-jr 2011, 121). Prior to his appointment, Djankov worked as a Chief Economist of the World Bank for fourteen years and during his term with CEDB Djankov presided over one of the most austere budgets in Europe. His Hayekian worldview surfaced during the protests in 2013 when he characterized the call for nationalization of the electric companies as “the road to the Gulag” (Djankov 2011b).

Ataka was the only one out of three parties not to mention “any condition for the potential partnership in the coalition” with CEDB (Genov 2010, 45). Realizing that this contradicts its rhetoric, Ataka struggled to explain its support for the neoliberal CEDB. “We did not have an option [...] and we did it with the hope that when you trust somebody, he will embark on the right way” (Siderov 2011b, 12). In regards to Ataka’s backing of conservative budgets Siderov explained: “this is a part of the compromises, i.e. the price we paid for the idea and hope, that CEDB will enter the road of the national interests” (Siderov 2011b, 12). However, the fact remains that this support translated to the promotion of neoliberal economics.

International issues convolute Ataka’s economic rhetoric as well. In fact its position on the crisis in neighboring Greece is neoliberal through and through. Ataka claims that the predicament is erroneously linked to the global economic downturn. Instead, “government spending” and “too much taxation” led to it. This is why “instead of pouring billions into Greece, the EU should throw it [Greece] out of the Eurozone” (Greece Must 2011, 8). Furthermore, Ataka unequivocally sides with the so-called Troika, which includes the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

The EC, the ECB and the IMF signed a memorandum for restrictions, which are not respected. Regardless of its leaking finances, Greece continues to employ an enormous number of state employees, does not sell its heavily indebted state enterprises and hands out bonuses and benefits of all kind. It does not raise the retirement age, and continues to pour subsidies into the state railway system (Greece Must 2011, 8).

Ataka’s neoliberal stance has ethnic overtones as well, whereas the Greeks’ “inherent” Mediterranean “laziness” is blamed for the crisis. In sum, from an economic point of view, Ataka’s response to the Greek crisis is thoroughly neoliberal and in sharp contrast to the left-wing responses it energized. Additionally, it is an example of the most substantial segment of Ataka’s discourse on economics—its tendency to abandon criticism of neoliberal economics, per se, through an ethnicization of economic problems.

Nationalism and Neoliberalism: The Roma Minority

Ataka’s schizophrenic economic rhetoric is most visible in its racism towards the 5% Roma minority. The Roma, the most impoverished minority in Eastern Europe, are accused of subjecting the ethnic Bulgarian population to “economic and cultural slavery” while “the state practices discrimination against the ethnic Bulgarians” (Todorov 2011a, 8). This “reverse discrimination” rhetoric credits multiculturalism and tolerance with the creation of “privileges, beyond the reach of the common Bulgarian citizen, leading to a chain of processes that turn the so called ‘discriminated against’ into privileged” (Todorov 2011a, 8). This fusion of economic grievances and racism is a major part of Ataka’s rhetoric:

The Bulgarian society witnesses how the entire welfare policy of the state is mainly turned towards easing the life of the gypsy population at the expense of the compliant tax payers [...] When will the Bulgarian state build at least one home for a young, ethnic Bulgarian family? A family that works for the lowest salary in the EU, pays taxes, insurance, sends its children to school, survives at the edge of destitution, abides the laws of the country and pays rent or a life-long mortgage? If the above mentioned program is only geared towards the gypsy ethnicity, we should ask ourselves—who is discriminated against? (Todorov 2011a, 8).

Throughout its issues, Ataka claims that 68% of all welfare programs in Bulgaria target Roma integration (Varbanova 2011, 12). This fabrication[10] accompanies the accusation that the Roma destroy rural areas: “the worst is that the gypsyfication of our villages is accompanied by a brutal genocide of the Bulgarian population” (Gypsies Destroy 2011, 7). Additionally, Ataka characterizes the Roma as a “social parasite” (Varbanova 2011, 12) whose high birth rate will make them the “leading ethnic group that will overload the state organism and precipitate its collapse” (Ivanov 2011, 8). This fusion between demographics, economics, and racism metamorphoses into a typical neoliberal rhetoric:

In regards to the problem that we try to solve in the last more than twenty years we have to ask—why does nobody help the socially strong to pull the cart, loaded with the socially weak? Why do we encourage ignorance and laziness? [...] Some drink and eat in the state restaurant throughout their entire lives, and others work all their lives to pay their bills! Legalized slavery! (Three Laws 2011, 4)

Figure 5: Roma neighborhood and playground in Pernik, Bulgaria, 2014.

This rhetoric spills into criticisms of international legal frameworks. Ataka characterizes the EU’s demands for integration as “utopian” since for more than fifteen centuries the Roma neither established a state, nor “contributed anything to human development” (Todorov 2011b, 8). Ataka accuses non-governmental organizations of abusing “enormous resources from the budget of the European funds” at the expense of ethnic Bulgarians (Avramov 2011, “The Wave” 12). It claims that, while the Western “pseudo-democrats” initially chastised Bulgaria for its treatment of the Roma, after the “brown crowds” headed to Western Europe they “toned down” this rhetoric—apparently recognizing the real problem this group creates (Shishmanova 2011, 14). Domestic post-1989 legislature is also a target of criticism. In particular, the Law against Discrimination is described as a tool that advances “the rights of the parasites” and stimulates:

gypsyfication, homosexualism, islamization and a number of other morally repulsive phenomena that belong to the misunderstood democracy, which turns into excessive freedom, and represents the efforts of the state to integrate a nomadic society, which in fact does not even define itself as Bulgarian, but as gypsy [...] The financially bound organizations that deal with gypsy integration and defense of their endless rights brand such reasoning as fascist, racist, discriminatory, ethnically intolerant, etc., and reproach the state (the prosecutors), which makes use of the illiterate and animally primal gypsy electorate, that sells its children as commodities and maims them on purpose (Todorov 2011b, 8).

This type of zealous, fascist rhetoric exposes Ataka’s schizophrenic discourse on neoliberalism. A “reverse discrimination” argument, strongly resembling the tirades of US neoliberals such as Glenn Beck, eclipses Ataka’s occasional criticism of the economic ills of contemporary capitalism. It ethnicizes Bulgaria’s socio-economic decline and blames it on the Roma, the group that is “10 times more likely to be poor than ethnic Bulgarians” (World Bank 2002) rather than on neoliberal economics itself. Historically, similar arguments were made in regards to Jews in Nazi Germany. Writing in the 1930s, Kenneth Burke noted that one of the highlights of Hitler’s rhetoric was to provide a “noneconomic interpretation of economic ills” (Burke 1939, 219).

Today, neoliberalism and racism reinforce each other through rhetoric that converts economic concerns into ethnic and racial demands in a process that does not necessarily invent racism but uses economically engendered anxieties to amplify already existing racial and ethnic prejudices. “In its current manifestation, racism survives through the guise of neoliberalism, a kind of repartee that imagines human agency as simply a matter of individualized choices, the only obstacle to effective citizenship and agency being the lack of principled self-help and moral responsibility” (Giroux 2003, 191). In fact Sebastian Job argues that, “the major ideological dynamic of the post-cold war era is the conflictive complicity of neoliberalism and various authoritarian and racist nationalisms” (Job 2001, 931).

Within Ataka’s racial and conspiratorial rhetoric, international legal frameworks and NGOs, rather than global economic inequalities, turn into the major enemies of the Bulgarian state. This is indicative of Ataka’s tendency to critique neoliberalism not as a “class project”, but as an externally imposed cultural and ethnic plot against the nation.

Islamophobia East and West

Ataka’s cultural definition of neoliberalism affects its view of Islam and Bulgaria’s Muslim minority as well. Bulgaria has the largest autochthonous Muslim population in the EU and they make up a larger percentage of the population than in Germany, France, or the United Kingdom (Ghodsee 2010, 520). Muslims in Bulgaria (10% of the population) live predominantly in the impoverished southeast of the country, but many regions host several ethnic groups. Ataka is the only political party in Bulgaria to propose that in the ethnically mixed areas, all political parties, regardless of political ideology, unite to nominate a common ethnic Bulgarian candidate to run against the representative of the party most popular with Bulgaria’s Muslims—the Movement for Rights and Freedom (MRF) (Antonova 2011b, 13).

Ataka claims that the “Turkish electorate” votes for the “anti-constitutional”, MRF “based on its herd instinct inscribed by the Koran” (Tomov 2011b, 12). Siderov and his party argue that Bulgaria’s Turkish minority is part of a global Islamization process that aims to turn Bulgaria “into a territory under Sharia law” and eliminate it from the map of Europe (Siderov 2011d, 1). It criticizes proposals to build new mosques because of their alleged use by fundamentalists. Hence Siderov defends the assault on the Sofia Mosque because “Ataka achieved one important goal—it placed into the daily agenda of society the theme of Islamization. Every media discusses the issue. It is true, we are paying a high price, but people approve our policy against Islamization” (After Ataka’s 2011, 3).

Ataka’s hatred towards the Bulgarian Muslims extends to an anti-Turkish rhetoric. It regards them as the “fifth column” used by Turkey to hinder the Bulgarian state. Ataka portrays the current Turkish government as “neo-Ottoman” and willing to incorporate the lands inhabited by Muslims in the Balkans into a new Ottoman Empire (The Political 2011, 8).

Ataka’s resentment of Turkey reached such a level that it became the first political party in Bulgaria to propose the construction of a wall on Bulgaria’s border with its southeastern neighbor. Additionally, Ataka is aware that today walls outline the Occident. “On the border of the European Union with Morocco, at the Spanish enclaves of Seuta and Melilla on the African coast, there is a concrete wall with barb wire. The United States isolates itself from Mexico with 3000 kilometers, triple wall, with a height of 3–4 meters, depending on the terrain” (Athens Isolates 2011, 10). In respect to these walls, as well as the one that divides Israelis and Palestinians, Alain Badiou states that the Berlin wall has only shifted. “It used to run between the totalitarian East and the democratic West; today it divides the rich capitalist North from the devastated poor South” (Badiou 2008, 56). Hence, Ataka’s proposal to build a wall on the Turkish border not only expresses hostility towards Turkey; it also symbolizes the desire to affirm Bulgaria’s belonging to the affluent and “civilized world.” “The collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe has evoked an obsession with ‘becoming European’, both in terms of EU membership, and also in terms of cultural identity implications of being European” (Koc 2010, 186). This has led to a hyperconsciousness about “Europeaness”, monolithically defined by white and bourgeois Western Europe, which is especially destructive in the margins of Europe where it deepens “(racialized) class divisions”, and re-defines attitudes towards more “Eastern” or more “Balkan” neighbors (Koc 2010, 181).

Ataka’s attitude towards the Bulgarian Muslims and Turkey extends to global Islam. Its foreign news section features predominantly articles about terrorism that bear titles such as “’The Religion of Peace”’ tore to pieces 21 people in Mumbai” and “The Monoculture Killed 37 people in Afghanistan and Pakistan.” Ataka blames Islam even for the hunger in Africa because of Muslim governments’ reluctance to reduce child birth rates.

This rhetoric presents Islam as inherently dangerous. In regards to the 2009 deadly incident in Fort Hood, Texas, when Major Nidal Hassan killed thirteen fellow US soldiers, Ataka concluded that, “the case demonstrates, once again, that there is no good Islam. Every ‘moderate’ Muslim might at any moment turn immoderate and adopt jihad against the ‘unbelievers’ in his surroundings, even if he was fed from their own hands” (Jihad 2011, 10).

Not surprisingly, its coverage of the “Arab Spring” is also skewed. Ataka perceives it only as the struggle between secular governments and Islamists. This rhetoric ties to a broader conspiracy theory. Ataka claims that “the United States Helps Build the Foundations of an Islamic Caliphate from Spain to Indonesia” under the guidance of President Obama (Andreev 2011, 14). Thus, after a deadly attack on Christian Copts in post-Mubarak’s Egypt Ataka concluded that “even when in downtown Manhattan, thousands of people protest against the genocide of the Copts, Obama’s media refuse to cover the event. This demonstrates that one of the goals of Obama’s union with the Middle Eastern Islamists is the uprooting of the remaining Christianity in the region” (Anti-Christian 2011, 10).

Thus, Ataka represents Barak Hussein Obama, as a major supporter of the “Islamic”, “anti-Christian”, Arab Spring and as the “American Gorbachev” who along with his advisor “the Indian Muslim, Fareed Zakharia [...] prepares the nation for the dawn of American hegemony and the transformation of the once ‘only superpower’ into one of the many Latin American nations” (Tasheva 2011d, 8). Criticisms of his administration adopted directly from American neoconservative sources accompany this rhetoric. For instance, Ataka published a Forbes magazine article that criticized “Obamacare”, “his large deficits”, and concluded that, “Obama hates business.” To this neoconservative piece, Ataka added its own touch and included a large photograph of a white homeless man with a caption underneath: “Under Obama the poverty among the white population is more visible than ever” (Mariotti 2011, 14). This is another example of Ataka’s tendency to fuse economic concerns with racial rhetoric and to simplify the economic conditions it addresses.

In this discourse Ataka echoes Western Islamophobia. Hence, its decision to shift focus from traditional anti-Semitism is reflective of a broader change within the European far-right. Ataka’s leader Volen Siderov gained notoriety in 2003 after he published his anti-Semitic book The Boomerang of Evil. In this controversial book, Siderov attributes every historical social calamity from Stalinism to Hitler’s Nazism to a Jewish conspiracy against Christian Orthodoxy. However, the seventy-five issues of Ataka’s daily examined in this study rarely reference Jews. Not only does Islamophobia replace traditional anti-Semitism in Ataka’s writing, but, in fact, Ataka advances a pro-Israeli rhetoric. For example, it included a CNN news piece entitled “Evangelicals Organize Visits in Jewish Settlements on the West Bank”, which claimed that “attracting European tourists would help people understand why Israelis continue to settle in the West Bank” (Flower 2011, 14). Additionally, Ataka ridiculed the Palestinian declaration of statehood in 2011 and negatively represented the General Secretary of the Arab League, Amr Moussa, as a person who wins sympathizers through “anti-Jewish rhetoric” (Ephron 2011, 14).

Atakadefended Israel in its diplomatic conflict with Turkey as well. The newspaper even included a statement by Israel’s far-right Foreign Minister, Avigdor Lieberman, who refused to deliver an official apology over the killing of nine Turkish peace activists by the Israeli army (Liebermann 2011, 10). Ataka supported his decision and characterized the Turkish demand as “impertinence” (Impertinence 2011, 11). It also portrayed the activists in the multinational, Gaza-bound flotillas as “fundamentalists.” “According to informed sources the members of the organization ‘Audacity of Hope’, which borrows its name from the biography of the American President Barak Hussein Obama, are adherents of radical Islamist organizations” (An American 2011, 10).

Ataka’s pro-Israeli rhetoric is not an aberration within the European and North American far-right discourse. The Norwegian fascist militant Andres Brejvik also expressed support of the state of Israel: “Sensible people should support Zionism (Israeli nationalism) which is Israel’s right to self-defense against Jihad” (The Norway 2011).

To sum up, in Ataka’s rhetoric Islam features as a multi-headed enemy with the local Muslim minority, Turkey, global Islam and Barack Obama featuring as the heads of the same monster. This polycephalus creature is so threatening to Christian Orthodoxy that it leads Ataka to sideline Jewish conspiracies and traditional anti-Semitism. All of this reflects Ataka’s identification with vocal and widespread Islamophobic segments of Western societies. This has at least three implications. First, this discourse is yet another issue which draws Ataka’s attention away from its purported concern with impoverishment and other outcomes of neoliberal economics. Second, through this rhetoric Ataka associates itself with other parties, movements and individuals across the West, especially in North America, that are far from critical of free market economics. Third, movements that use the term neoliberalism, such as Ataka, are automatically described as “anti-Western”, “anti-American”, and/or “Eurosceptic”. The analysis of Ataka’s official newspaper indicates that this is far too simplistic. Instead Ataka endorses a particular view of European politics that is shared across the West and does not stem from an indigenous and a nationalist desire to delink from the West and Europe in particular. What is more, its identification with the European and North American far-right political forces once again brings to the fore Ataka’s noneconomic understanding of neoliberalism.

Identifications with the West

Ataka’s tendency to channel social anger against minorities, immigrants and Islam, leads it to identify itself with “the patriots in Europe who will stop the project ‘Eurabia [...] designed by Brussels pro-Islamic oligarchy’” (Tasheva 2011e, 11) and resist the Muslims’ desire to bring “their primitive tribal traditions to the European land” (The Islamic 2011, 12). It legitimizes its extreme position through the popularity of the far-right and the Western anti-Islamic attitudes:

According to the new branding, all who hold to national identity and define themselves as Christians, are stigmatized as “right-wingers” and “conservatives.” Those who are for “multiculturalism”, or in other words for the Islamization of Europe, automatically become “left” and “liberals.” The nations want Christianity and national identity. They don’t want to support the crowds of Mohamedanian parasites, who the left-liberals and the freemasons in Brussels let in Europe in exchange for petrodollars (Tasheva 2011e, 11).

Ataka claims that in Bulgaria, Italy, Austria, and the Netherlands, the “nationalist” parties gained enough support to help safeguard “nationally responsible, conservative parties and coalitions” (Shishmanova 2011, 14). In this way, it legitimizes its racist discourse not only through association with the European far-right but also through the statements of less extremist right-wing leaders and parties. It frequently quotes Angela Merkel’s claim that multiculturalism has failed as well as Nicolas Sarkozy’s statement that “Islam is at the base of the problem of integration of the Muslims” (Avramov 2011, 12). But Ataka does not confine its discourse to Europe and follows the anti-Islamic rhetoric across the Atlantic Ocean as well. For instance, it expressed admiration for the controversial commission on the “Islamic Radicalization in the US”, organized by US Republican Congressman, Peter King (Forty US 2011, 10).

Ataka’s identification with Western far-right discourse surfaced when it passionately tried to dissociate the far-right populist parties from the Norwegian terrorist attacks carried out by Andres Brejvik. Ataka declared that July 22, 2011 will be remembered as a day of calamity “not because of the 92 victims, among whom are at least 85 children between the ages on 15–22, but because of the insolent attempts to use the event to the benefit of global Islam and in particular—the Islamization of Europe” (Tasheva 2011e, 10). Ataka vigorously denied that Brejvik is a Christian conservative and portrayed him instead as a freemason. It covered the tragedy as a plot of the Norwegian Socialist government and their “globalist” partners to discredit the “increasingly more popular conservative, nationalist parties in Europe, who want to halt Islamization” (Tasheva 2011e, 10).

Ataka’s coverage of the attacks reveals not only its strong attachment to the Western European far-right; it once again highlights Ataka’s noneconomic understanding of neoliberalism. In an article entitled “The Neoliberal Propaganda Takes Advantage of the Tragedy in Scandinavia”, Ataka defined as neoliberals “the Socialist coalition of Jens Stoltenberg, as well as the liberal circles, implementing the Islamization of Europe” (The Norwegian 2011, 1). Ataka defines neoliberalism not as an economic ideology—e.g. faith in the free market—but as a particular practice of multiculturalism, using racist claims about Islamization to conceal the larger economic context in which contemporary global politics makes sense.

Similarly, during the 2011 riots in England, Ataka reaffirmed this noneconomic understanding of neoliberalism. It preferred to claim that the riots originated in the “multiethnic areas”, rather than the poorest neighborhoods (The Multicultural 2011, 11). It stated that the 'race war’ showed that “multiculturalism in England failed totally” and argued that “the aggression of the people of color now transgresses the limits of tolerance even in a liberal society such as the English one” (Multiculturalism in 2011, 11). Ataka concluded that “the hypocrisy of multiculturalism continues to grow because of fear that if a public debate starts the outcome would not be to the benefit of neoliberalism” (The Multicultural 2011, 11) and summarized the result of the riots in the following way: “The racial riot proved how ineffective the neoliberal model is, because it tied the hands of the people in uniforms so they can’t control the disturbances” (The Jihad 2011, 10) while “the colored marauders destroyed whatever the white man has created” (The Multicultural 2011, 11).

This noneconomic treatment of neoliberalism is a permanent feature of Ataka’s discourse. The reason for this is the fact that its capacity to fuse issues of poverty and inequality with issues of identity is crucial for the functioning of far-right populist discourse in the context of a neoliberalized economy.

Conclusion

The analysis of Ataka’s newspaper demonstrates that this political party articulates social anger engendered by the painful neoliberal reforms in Bulgaria. The capacity of such movements to articulate this anger is what determines their success. The retreat of traditional leftist parties to the right, as well as the contemporary tendency of mainstream discourse to ignore class and inequality, opens an opportunity for far-right parties to engage in what Kenneth Burke (1937) described as the “stealing back and forth of symbols” (135). According to Burke, during this process a sect identifies with the orthodoxy through a claim that it truly embodies the orthodoxy (135). In the case of the far-right, these parties claim to be the authentic representatives of the workers.

But the direct appropriation of the symbols of the left is only one component of Ataka. What is more, it is the most unscrupulous one. For example, Ataka claimed that Hugo Chavez and Fidel Castro have contributed “not only to the decadence of human morals, but also to the decline of important civilizational processes on the planet” (Solakov 2011, 12). However, after Hugo Chavez passed away Ataka’s leader declared on national television that “Chavez is an example of what we should do in Bulgaria.”

But, the fact remains that its collective identity is firmly embedded in xenophobia and nationalism rather than socialism and multicultural internationalism. Through its emphasis on Islamophobia and anti-multiculturalism, Ataka follows the example of its counterparts in Western Europe. Thus, the description of Ataka and other anti-establishment post-socialist parties as “anti-Western” or “Eurosceptic” is misleading. On the contrary, through their hatred against minorities, immigrants and homosexuals they simply endorse a particular vision of Europe that is not unique to the far-right in the former Eastern bloc.

But Ataka’s discourse reveals that its success does not depend primarily on its opportunistic stealing of the symbols of the left. The key to its achievement lies in its capacity to articulate social anger along issues of identity. However, the complexity of the cultural front coupled with a social context of economic instability requires Ataka to operate with diverse, ambiguous, and often contradictory demands. The analysis of the seventy-five issues of Ataka’s newspaper shows that the expression of demands strictly along economic lines is rarer than their articulation along cultural and ethnic cleavages. If Laclau’s theoretical framework is taken into account, nationalism features as the foremost popular signifier that infuses economic issues with identity politics. This is why the most impoverished group in Bulgaria, the Roma, could be represented as an economic oppressor.

But this emphasis on ethno-religious issues could also be seen as a result of neoliberalism’s far reach into society. In the process of globalization small countries feel not only economic decline but cultural degradation. One of the earliest theorists of contemporary capitalism, Karl Polyani (1957), argued that the encounter between a weaker and a stronger society could produce a social calamity that is “primarily a cultural not an economic phenomenon”, whereas “not economic exploitation, as often assumed, but the disintegration of the cultural environment of the victim is then the cause of the degradation” (164).[11] Aihwa Ong, also broadens the scope and argues that as a technology of government, neoliberalism is not simply an “Americanizing project” but a new mode of political organization, which actively reconfigures relationships between governing and the governed, power and knowledge, and sovereignty and territoriality (Ong 2006, 3). She claims that in neoliberalism “the elements that we think of as coming together to create citizenship—rights, entitlements, territoriality, a nation—are becoming disarticulated and rearticulated with forces set into motion by market forces”, because “the territoriality of citizenship, that is, the national space of the homeland, has become partially embedded in the territoriality of global capitalism, as well as in spaces mapped by the interventions of nongovernment organizations (NGOs)” (Ong 2006, 6-7). These highly destabilizing effects of neoliberalism that reach beyond the economic sphere, help far-right movements to maintain a nationalist popular signification that regards neoliberalism primarily as a socio-cultural scheme. Hence Ataka reacts to neoliberalism’s perceived cultural role as a project that supports “global Islam”, minorities, post-nationalism, multiculturalism, and immigration.

Ataka’s leader himself noted the oversaturation of economic concerns with issues of identity. In a chieftain party such as Ataka, self-criticism is rare but after its disastrous performance in the elections of October 2011 (Siderov gained 2% of the presidential vote), very cautiously and perhaps unintentionally Siderov drew an important conclusion. When asked whether 2011 signaled the end of Ataka, he answered that on the contrary, 2012 will mark a new phase because the movement will start to stress its economic agenda and “not only the ethno-religious [agenda] which was emphasized a great deal throughout the years, and which, in reality, made us noticeable” (Volen Siderov Sees 2011).

Indeed during the historic protests and self-immolations that toppled the government in 2013, Ataka seemed to sideline some of its ethnic concerns while it prioritized arguments against the electric companies and “market fundamentalism.” However, it is highly improbable that Ataka will transform the structure of its chain of demands to be held by an economic, and genuinely anti-neoliberal signifier. It is more likely that its (mis)understanding of neoliberalism will remain the same as the one expressed in the epitaph at the beginning of this article. Nevertheless, one must not underestimate right-wing populists’ unscrupulous stealing of left-wing rhetoric. They are especially enthusiastic to do this during economic crisis when the population is particularly vulnerable. But there is also the opposite danger—many people dismiss the leftist themes they appropriate precisely because they are uttered by parties like Ataka. While Siderov’s erratic and scandalous behavior helps him draw media publicity, it has also had a significant backlash.[12] At this point in time, most Bulgarians view Siderov as unstable and even mentally ill. Mainstream neoliberal commentators take advantage of this and associate any criticism of neoliberalism with Ataka and Siderov.

Figure 6: “Ataka Says that Energy Companies Should Be in Bulgarian Hands. Stop the Electricity Price Hikes!” Ataka’s graffiti in Pernik, Bulgaria 2015.

But the most dangerous and most successful feature of Ataka is its capacity to popularize racist discourse in the media and the parliament. In other words, the “stealing back and forth” of symbols theorized by Kenneth Burke is not a one-way process. At this point of time, virtually every political party in Bulgaria with the exception of the Movement for Rights of Freedoms engages in racist and nationalistic rhetoric. Indeed, Ataka constantly complains that other parties “steal” its proposals. The most recent example of the spread of racism across political lines was exemplified by the current Minister of Health Petar Moskov, from the Reformist Bloc, a coalition of the most anti-communist, pro-EU, pro-Western and neoliberal parties in Bulgaria. After an incident with an ambulance in a Roma ghetto, Moskov banned ambulances from entering Roma neighborhoods across Bulgaria. The overwhelming support for his decision ranged from his liberal followers to skinheads, soccer hooligans and Neo-Nazi groups.[13] In this way, the rhetoric that Ataka introduced in the Bulgarian parliament bears fruits. Thus, while Ataka was the only party to propose the building of a wall on the border with Turkey in 2011, most other parties gradually adopted the idea and today a barbed wire fence to stop migrants is a reality.

That is why a major task of people on the left should be to unmask the fact that far-right populist movements do not challenge the existing economic structures. Their only “achievement” is to sow ethnic hatred in an already tense social milieu. In many cases the unmasking does not have to be done only through an analysis of their manifestos or speeches. In the case of Ataka, we have solid empirical evidence that when it got to power, not only it did not make the state more “social”, but it helped the major party to continue deep neoliberal reforms. From 2009 to 2012, a period during which Ataka backed CEDB, Bulgaria reduced its budget deficit from 4,4% of GDP to less than 1% (Djankov 2013). This was at the expense of dramatic reductions of government spending and the increase of the mandatory retirement age by two years, among other neoliberal reforms. In the last elections (2014), another far-right party called “The Patriotic Front” also managed to enter parliament.[14] As Ataka did five years ago, the Patriotic Front also joined a governing coalition with CEDB and the liberal Reformist Bloc. Today the “patriots” are backing CEDB’s push to privatize public schools and to carry out draconian neoliberal reforms in the healthcare system. This is yet another proof that far-right populism in Bulgaria fully supports neoliberalism even though it speaks against it.

The recent victory of the Greek SYRIZA provides some hope that the new left can also make viable arguments during crisis. Despite the dominance of anti-communist discourses that undermine every criticism of neoliberalism, there have been some positive signs in Bulgaria as well. Although, the winter protests of 2013 were a complex phenomenon difficult to bracket as left-wing or right-wing, the calls for nationalization of the electricity companies, as well as the dismissal of the entire political system as corrupt (no political parties were allowed to attend the protests) were a novelty for the post-1989 period on which future resistance could build. Additionally, in the last few years some young people have attempted to imagine a different world. A direct result of this was the emergence of several social centers, such as Xaspel, Adelante and the Solidarity center in Varna, that provide alternative spaces for discussion and various other activities counter to neoliberalism. Recently a number of young left-wing journalists established a lively discussion network, called Solidarna Bylgaria, which is now at the forefront of the struggle against the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). There has also been a growing concern among many Bulgarians about the spread of racist and homophobic discourse. Thus a diverse group of people coalesced around its shared opposition to an annual international fascist march referred to as “Lukov March.” The torch-lit march has been held in Sofia every February since 2003 to honor a World War II Bulgarian army general known for his pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic views.[15] In the last few years a constantly growing counter-march has been held on the same day. These and other similar developments show that although timid and slow, resistance against neoliberalism and neofascism in Bulgaria is growing.

Figure 7: Anti-Lukov March Protest in Sofia Bulgaria, February 2015.

Notes

1This is how Volen Siderov describes himself in the biographical note on the cover of his numerous books: “The author participated in the dissident anti-communist movement before the 10th of November 1989 and in the creation of the political opposition to the communist party—Union of Democratic Forces (UDF), as well as the free press. One of the few in this sphere who has never been connected to the Bulgarian Communist Party and the secret services of the communist regime.”

2Тhe growing hostility between Russia and the EU has invigorated the argument that these parties are “anti-European”, because of overblown claims that Russia funds them and shares their ideology. Better known examples of this discourse include Snyder, Timothy. 2014. Ukraine: The Antidote to Europe’s Fascists, The New York Review of Books. May 27. Accessed February 10, 2015. http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2014/may/27/ukraine-antidote-europes-fascists/ and Shekhovtsov, Anton. 2014. The Kremlin’s Marriage of Convenience with the European Far Right. Open Democracy. April 28. Accessed February 10, 2015. https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/anton-shekhovtsov/kremlin%E2%80%99s-marriage-of-convenience-with-european-far-right.

3However, one must note that this feature is no longer shared only by the far-right, as parties across the political spectrum, including some liberal ones, have utilized this rhetoric.

4The study also notes that there is a high support for Ataka in the traditionally wealthy areas around the South seaside. In 2006 Ataka’s highest vote was in Nessebar, a historical Black Sea resort city, recognized as a cultural monument by UNESCO. This is one of the richest places in Bulgaria and it is one of the very few Bulgarian municipalities that contributes to the state budget rather than draw from it (Ivanova 2007, 17). The study notes that a significant section of the residents of Nessebar and other Black Sea resorts where Ataka performed very well owned at least a bar or a small hotel.

5The citations from Ataka’s newspaper and all other sources in Bulgarian are translated in English and marked by an asterisk in the reference section.

6Political parties in Bulgaria are publicly funded based on the votes they receive. Each vote brings the party 12 BGN (approximately $7) For 2014 Ataka received 6,170 000 BGN (approximately $3,800 000).

7For an analysis of Siderov’s books see Marinos, Martin and Georgi Medarov. 2015. Postsocialism and the Rise of the Bulgarian Far-Right. In The Far-Right Across Europe. Edited by Fred Leplat. London: Merlin/Resistance Book. (forthcoming).

8A notorious case is Philip Dimitrov, Bulgaria’s first anti-communist Prime Minister turned into an American academic and a “specialist” on what he describes as the “red-brown populism.” It is stunning (but entertaining) to read the incredibly diverse group of individuals, countries, parties and movements, which he treats as indistinguishable populist phenomena. He lists Hamas, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, North Korea, the Bulgarian or Slovak Mafia, the Taliban, Skinheads, Iran, and Chavez. Dimitrov, Philip. 2009. Does “Populism” in Europe’s New Democracies Really Matter. Demokratizatsya 17 (4): 310–323.

9The move to the right of the BSP continues to this day. After SYRIZA’s victory in Greece, BSP’s long-term leader and currently the president of the Party of European Socialists (PES) in the European Parliament, Sergei Stanishev, warned that the Greek leftist party is dangerous because of its populism.

10According to the National Statistical Institute of Republic of Bulgaria. 2012. European System for Integrated Statistics of Social Welfare, 2, only 1.23% of social welfare goes for alleviation of “social exclusion”.

11Cultural degradation is especially visible in Bulgaria’s cinema industry. There were 3,500 cinemas in Bulgaria in 1989. Only a decade later their number had shrunk to 68. Ivanova, Dimitrina. 1996. Bulgarian Cinema Today. In Rossen Milev Ed., Bylgarsko Mediznanie [Bulgarian Media Knowledge], Balkan Media, Sofia: 369. 368–375.

12Siderov’s most recent scandal erupted in January 2014 when he assaulted a French diplomat on a flight from Sofia to Varna in Bulgaria. After the plane landed Siderov punched a policeman at the airport. In 2011, the party barely survived a soap opera-like drama after it became public that Siderov has an affair with Denitsa Gadzheva, the leader of Ataka’s youth wing and a fiancŽ of his stepson and MEP of Ataka, Dimitar Stoyanov. At this point, Kapka, Siderov’s wife and the editor of the party newspaper divorced him and quit her job. Stoyanov, her son and MEP of Ataka, also started a public feud with his former step-father, party leader and up to that point in time, secret lover of his fiancŽ.

13For an analysis of Moskov’s use of racist rhetoric in order to present broad anti-welfare policies as directed against minorities see Tsoneva, Jana. 2015. Bulgaria’s Creeping Apartheid, Part I: Mobilizing Racism to Shrink the Social State. LeftEast http://www.criticatac.ro/lefteast/bulgarias-creeping-apartheid-ii-liberal-dehumanization/.

14Like Ataka, the Patriotic Front emerged out of the television screen. In fact, its main slogan is “the party of SKAT.” SKAT is the television network owned by Valery Simenov, the leader of the Patriotic Front. In some respects the Patriotic Front is more “radical” than Ataka. For instance, one of its proposals is to intern Roma people in camps where they can work unused land.

15Hristo Lukov was assassinated by an urban communist guerrilla group in 1943. The actual killer of Lukov was a female Bulgarian fighter of Jewish descent who allegedly shot him in front of his mother. All of these details have made Lukov a particularly appealing “martyr” for neofascists. What is more disturbing is the fact that despite his openly fascist actions he has been enshrined as a “victim of communism” by liberals and his name, along with that of many other fascists and pro-Nazi officials is engraved on the monument of the “victims of communism” in downtown Sofia.

References

After Ataka’s Protest in Sofia the Noise of the Mosque is Reduced and the Mats Removed. 2011. Ataka, June 3, 3.

An American Palestine-bound Ship is Held. 2011. Ataka, July 4, 10.

Andreev, Todor. 2011. USA Aids the Establishment of a Caliphate from Spain to Indonesia. Ataka, June 20, 14.

Anti-Christian Repression in ‘Democratic’ Egypt. 2011. Ataka, June 28, 10.

Antonova, Emilia. 2011a. Ataka Has the Support of Business, the Youth and the Intelligentsia. Ataka, August 2, 13.

Antonova, Emilia. 2011b. CEDB Did Not Let Volen Siderov in ‘Antimafia’. Ataka, June 30, 13.

Antonova, Emilia. 2011c. The Municipality Turned into A Realty Agency. Ataka, July 21, 13.

Ataka’s Gathering Confirmed Siderov and Shopov as a Presidential Pair. 2011. Ataka, July 18, 1.

Ataka Liked Top Entrepreneur for a Mayor of the Capital. 2011. Ataka, June 29, 1.

Athens Isolates Itself from Turkey with a 120 Kilometers-Long Ditch. 2011. Ataka, August 10, 10.

Avramov, Dimitar. 2011. The Wave of Domestic Crime Reveals the Weakness of the State. Ataka, July 27, 12.

Badiou, Alain. 2008. The Meaning of Sarkozy. Tr. David Fernbach. London: Verso.

Bulgaria Shocked as Nationalists Assault Praying Muslims in Sofia Mosque. 2011. Sofia News Agency. 20 May. Accessed August 15, 2014. http://www.novinite.com/ view_news.ph p?id=128474.

Burke, Kenneth. 1937. Attitudes Toward History. Berkley: University of California Press.

Burke, Kenneth. 1939. The Rhetoric of Hitler’s Battle. In On Symbols and Society, edited by Joseph Gusfield, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Central Electoral Commission (ЦИК). Accessed August 15, 2014. http://www.cikbg.org/h.

Dineva, Stanka. 2011. I Want to Bring Back the Youth. Ataka, August 1, 13.