Digital Workers of the World Unite! A Framework for

Critically Theorising and Analysing Digital Labour

Christian Fuchs* and Marisol Sandoval†

*University of Westminster, christian.fuchs@uti.at

†City University London, marisol.sandoval.1@city.ac.uk

Abstract: The overall task of this paper is to elaborate a typology of the forms of labour that are needed for the production, circulation, and use of digital media. First, we engage with the question what labour is, how it differs from work, which basic dimensions it has and how these dimensions can be used for defining digital labour. Second, we introduce the theoretical notion of the mode of production as analytical tool for conceptualizing digital labour. Modes of production are dialectical units of relations of production and productive forces. Relations of production are the basic social relations that shape the economy. Productive forces are a combination of labour power, objects and instruments of work in a work process, in which new products are created. Third, we have a deeper look at dimensions of the work process and the conditions under which it takes place. We present a typology that identifies dimensions of working conditions. It is a general typology that can be used for the analysis of any production process. Fourth, we apply the typology of working conditions to the realm of digital labour and identify different forms of digital labour and the basic conditions, under which they take place. Finally, we discuss political implications of our analysis and what can be done to overcome bad working conditions that digital workers are facing today.

Keywords: critical theory, critical political economy of communication and the media, social theory, digital labour, digital work, digital media, philosophy

Muhanga is an enslaved miner in Kivu (Democratic Republic of Congo). He extracts cassiterite, a mineral that is needed for the manufacturing of laptops and mobile phones: “As you crawl through the tiny hole, using your arms and fingers to scratch, there’s not enough space to dig properly and you get badly grazed all over. And then, when you do finally come back out with the cassiterite, the soldiers are waiting to grab it at gunpoint. Which means you have nothing to buy food with. So we’re always hungry” (Finnwatch 2007, 20).

The Chinese engineer Lu assembles mobile phones at Foxconn Shenzhen. He reports about overwork and exhaustion: “We produced the first generation iPad. We were busy throughout a 6-month period and had to work on Sundays. We only had a rest day every 13 days. And there was no overtime premium for weekends. Working for 12 hours a day really made me exhausted” (SACOM 2010, 7; for an analysis of Foxconn see also Sandoval 2013).

In Silicon Valley, the Cambodian ICT (information and communications technology) assembler Bopha has been exposed to toxic substances. He highlights: “I talked to my co-workers who felt the same way [that I did] but they never brought it up, out of fear of losing their job” (Pellow and Park 2002, 139).

Mohan, a project manager in the Indian software industry who is in his mid-30s, explains, “Work takes a priority. […] The area occupied by family and others keeps reducing” (D’Mello and Sahay 2007, 179). Bob, a software engineer at Google explains that, “because of the large amounts of benefits (such as free foods) there seems to be an unsaid rule that employees are expected to work longer hours. Many people work more than 8 hours a day and then will be on email or work for a couple hours at home, at night as well (or on the weekends). It may be hard to perform extremely well with a good work/life balance. Advice to Senior Management—Give engineers more freedom to use 20% time to work on cool projects without the stress of having to do 120% work” (data source: www.glassdoor.com).

Ann, a web designer, writer, and illustrator, offers her services on the freelance market platform People Per Hour that mediates the creation and purchase of products and services that are not remunerated by worked hours, but by a fixed product price. She describes her work:

My design styles are as broad as my client base, from typical hard hitting, sound, clear, and concise business branding, to more stylised and fluid hand drawn or illustrated work. I relish working to a deadline, and although I often work to very specific criteria, some clients are looking for a moment of inspiration, and that's where I excel. I'm always ready for a challenge, and providing the brief is concise and well conceived. I can produce work to a very tight schedule. If you are online, you will see amendments almost immediately! (data source: peopleperhour.com).

The working lives of Muhanga, Lu, Bopha, Mohan, Bob, and Ann seem completely different. Muhanga extracts minerals from nature. Lu and Bopha are industrial workers. Mohan, Bob and Ann are information workers creating either software or designs. They work under different conditions, such as slavery, wage labour, or freelancing. Yet they have in common that their labour is in different ways related to the production and use of digital technologies and that ICT companies profit from it. In this paper we discuss the commonalities and differences of the working lives of workers like these by identifying different dimensions of digital labour.

Section 1 introduces a cultural-materialist perspective on theorising digital labour. Section 2 discusses the relevance of Marx’s concept of the mode of production for the analysis of digital labour. Section 3 introduces a typology of the dimensions of working conditions. Section 4 based on the preceding sections presents a digital labour analysis toolbox. Finally, we draw some conclusions in section 5.

1. (Digital) Work and Labour: A Cultural-Materialist Perspective

The digital labour debate has in a first phase focused mainly on understanding the value creation mechanisms on corporate social media such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter. Authors have for example discussed the usefulness of Karl Marx’s labour theory of value (Fuchs 2010, Arvidsson and Colleoni 2012, Fuchs 2012b, Scholz 2013), how the notion of alienation shall be used in the context of digital labour (Andrejevic 2012, Fisher 2012), or if and how Dallas Smythe’s concept of audience labour can be used for understanding digital labour (for an overview discussion see Fuchs 2012a). The book Social Media: A Critical Introduction (Fuchs 2014b) provides a general introduction to many of these issues. The general task has been to understand and conceptualise a situation in which users under real-time and far-reaching conditions of commercial surveillance create a data commodity that is sold to advertising clients. This involved a discussion of the question of who exactly creates the value that manifests itself in social media corporations’ profits. But going beyond these initial debates, studying digital labour requires paying attention to digital labour in all its forms.

In approaching a definition of digital labour one can learn from debates on how to define cultural and communication labour.

1.1. Defining Cultural Labour

There exists a latent debate between Vincent Mosco and David Hesmondhalgh about how to define cultural and communication work and where to draw the boundaries. According to Hesmondhalgh cultural industries “deal primarily with the industrial production and circulation of texts” (Hesmondhalgh 2013, 16). Thus cultural industries include broadcasting, film, music, print and electronic publishing, video and computer games, advertising, marketing and public relations, and web design. Cultural labour is therefore according to this understanding all labour conducted in these industries. Cultural labour deals “primarily with the industrial production and circulation of texts” (Hesmondhalgh 2013, 17). Following this definition Hesmondhalgh describes cultural work as “the work of symbol creators” (Hesmondhalgh 2013, 20).

Vincent Mosco and Catherine McKercher argue for a much broader definition of communication work, including “anyone in the chain of producing and distributing knowledge products” (Mosco and McKercher 2009, 25). In the case of the book industry, this definition includes not only writers but, equally, librarians and also printers.

Hesmondhalgh’s definition of cultural industries and cultural work focuses on content production. Such a definition tends to exclude digital media, ICT hardware, software, and Internet phenomena such as social media and search engines. It thereby makes the judgment that content industries are more important than digital media industries. It is idealistic in that it focuses on the production of ideas and excludes the fact that these ideas can only be communicated based on the use of physical devices, computers, software, and the Internet. For Hesmondhalgh (2013, 19) software engineers for example are no cultural workers because he considers their work activity as “functional” and its outcomes not as text with social meaning. Software engineering is highly creative: it is not just about creating a piece of code that serves specific purposes, but also about writing the code by devising algorithms, which poses logical challenges for the engineers. Robert L. Glass (2006) argues that software engineering is a complex form of problem solving that requires a high level of creativity that he terms software creativity. Software is semantic in multiple ways: a) when its code is executed, each line of the code is interpreted by the computer which results in specific operations; b) when using a software application online or offline our brains constantly interpret the presented information; c) software not only supports cognition, but also communication and collaboration and therefore helps humans create and reproduce social meaning. Software engineers are not just digital workers. They are also cultural workers.

Hesmondhalgh opposes Mosco’s and McKercher’s broad definition of cultural work because “such a broad conception risks eliminating the specific importance of culture, of mediated communication, and of the content of communication products” (Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2011, 60). Our view is that there are many advantages of a broad definition as:

1. it avoids “cultural idealism” (Williams 1977, 19) that ignores the

materiality of culture,

2. it can take into account the connectedness of technology and content, and

3. it recognizes the importance of the global division of labour, the exploitation

of labour in developing countries, slavery and other bloody forms of labour and

thereby avoids the Western-centric parochialism of cultural idealism.

Probably most importantly, a broad conception of cultural work can inform political solidarity: “A more heterogeneous vision of the knowledge-work category points to another type of politics, one predicated on questions about whether knowledge workers can unite across occupational or national boundaries, whether they can maintain their new-found solidarity, and what they should do with it” (Mosco and McKercher 2009, 26).

Likewise, Eli Noam opposes the separation of hardware and content producers and argues for a broad definition of the information industry: “Are the physical components of media part of the information sector? Yes. Without transmitters and receivers a radio station is an abstraction. Without PCs, routers, and servers there is no Internet” (Noam 2009, 46). Noam argues for a materialist unity of content and hardware producers in the category of the information industry.

While some definitions of creative work and creative industries are input- and occupation-focused (Caves 2000, Cunnigham 2005, Hartley 2005), the broad notion of cultural work we are proposing focuses on industry and output. Input- and output-oriented definitions of cultural work/industries reflect a distinction that already Fritz Machlup (1962) and Daniel Bell (1974) used in their classical studies of the information economy: the one between occupational and industry definitions of knowledge work. Our approach differs both from input-oriented definitions and narrow output-oriented definitions.

We argue that cultural workers should be seen as what Marx termed Gesamtarbeiter. Marx describes this figure of the collective worker (Gesamtarbeiter) in the Grundrisse where he discusses labour as communal or combined labour (Marx 1857/1858, 470). This idea was also taken up in Capital, Volume 1, where he defines the collective worker as “a collective labourer, i.e. a combination of workers” (Marx 1867, 644), and argues that labour is productive if it is part of the combined labour force: “In order to work productively, it is no longer necessary for the individual himself to put his hand to the object; it is sufficient for him to be an organ of the collective labourer, and to perform any one of its subordinate functions” (ibid). The collective worker is an “aggregate worker” whose “combined activity results materially in an aggregate product” (ibid, 1040). The “activity of this aggregate labour-power” is “the immediate production of surplus-value, the immediate conversion of this latter into capital” (ibid).

The question of how to define cultural and eventually also digital labour has to do with the more general question of how to understand culture. It therefore makes sense to pay some attention to the works of one of the most profound cultural theorists: Raymond Williams.

1.2. Cultural Materialism

In his early works, Raymond Williams was trying to understand working-class culture in contrast to bourgeois culture, which illustrates his genuinely socialist position and interest in culture. But although Williams stresses the focus on totality, i.e. culture as “the way of life as a whole” (Williams 1958, 281) and “a general social process” (Williams 1958, 282), he in his early works tended to categorically separate culture and the economy: “even if the economic element is determining, it determines a whole way of life” (Williams 1958, 281). This notion of determination implies that the two realms of the economy and culture are connected, but that in the first instance they are also separate.

Later, in Marxism and Literature, Raymond Williams questioned Marxism’s historical tendency to see culture as “dependent, secondary, ‘superstructural’: a realm of ‘mere’ ideas, beliefs, arts, customs, determined by the basic material history” (Williams 1977, 19). He discusses various concepts that Marxist theories have used for conceptualising the relationship of the economy and culture: determination, reflection, reproduction, mediation, homology. He argues that these concepts all assume a relationship between the economy and culture that to a varying degree is shaped by causal determination or mutual causality. But all of them would share the assumption of “the separation of ‘culture’ from material social life” (Williams 1977, 19) that Williams (1977, 59) considers to be “idealist”. In Williams view the problem with these approaches is not that they are too economistic and materialist but quite on the contrary that they are not “materialist enough” (Williams 1977, 92).

Williams (1977, 78) argues that Marx opposed the “separation of ‘areas’ of thought and activity”. Production would be distinct from “consumption, distribution, and exchange” as well as from social relations (Williams 1977, 91). Productive forces would be “all and any of the means of the production and reproduction of real life”, including the production of social knowledge and co-operation (Williams 1977, 91). Politics and culture would be realms of material production: ruling classes would produce castles, palaces, churches, prisons, workhouses, schools, weapons, a controlled press, etc. (Williams 1977, 93). Therefore Williams highlights the “material character of the production of a social and political order” and describes the concept of the superstructure an evasion (Williams 1977, 93). Here, Williams reflects Gramsci’s insight that “popular beliefs” and “similar ideas are themselves material forces” (Gramsci 1988, 215).

Raymond Williams (1977, 111) formulates as an important postulate of Cultural Materialism that “[c]ultural work and activity are not […] a superstructure” because people would use physical resources for leisure, entertainment, and art. Combining Williams’ assumptions that cultural work is material and economic and that the physical and ideational activities underlying the existence of culture are interconnected means that culture is a totality that connects all physical and ideational production processes that are connected and required for the existence of culture. Put in simpler terms this means that for Williams the piano maker, the composer, and the piano player all are cultural workers.

Williams (1977, 139) concludes that Cultural Materialism needs to see “the complex unity of the elements” required for the existence of culture: ideas, institutions, formations, distribution, technology, audiences, forms of communication and interpretation, worldviews (138f). A sign system would involve the social relations that produce it, the institutions in which it is formed and its role as a cultural technology (Williams 1977, 140). In order to avoid the “real danger of separating human thought, imagination and concepts from ‘men’s material life-process’” (Williams 1989, 203), one needs to focus on the “totality of human activity” (Williams 1989, 203) when discussing culture: We “have to emphasise cultural practice as from the beginning social and material” (Williams 1989, 206). The “productive forces of ‘mental labour’ have, in themselves, an inescapable material and thus social history” (William 1989, 211). Marx expressed the basic assumption of Cultural Materialism well by stressing that the “production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 42). The production of ideas is therefore the “language of real life” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 42). “Men are the producers of their conceptions, ideas, etc., that is, real, active men, as they are conditioned by a definite development of their productive forces and of the intercourse corresponding to these, up to its furthest forms” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 42). Thinking and communicating for Marx are processes of production that are embedded into humans’ everyday life and work. Human beings produce their own capacities and realities of thinking and communication in work and social relations.

In his later works, Williams stressed that it is particularly the emergence of an information economy in which information, communication, and audiences are sold as commodities that requires rethinking the separation of the economy and culture and to see culture as material. “[I]nformation processes […] have become a qualitative part of economic organization” (Williams 1981, 231). “Thus a major part of the whole modern labour process must be defined in terms which are not easily theoretically separable from the traditional ‘cultural’ activities. […] so many more workers are involved in the direct operations and activations of these systems that there are quite new social and social-class complexities” (Williams 1981, 232).

As information is an important aspect of economic production in information societies, the culture concept cannot be confined to popular culture, entertainment, works of arts, and the production of meaning through the consumption of goods, but needs to be extended to the realm of economic production and value creation. Cultural labour is a crucial concept in this context.

1.3. A Materialist Notion of Cultural Labour

Inspired by Raymond Williams’ cultural materialism, it is feasible to argue for a broad understanding of cultural and digital labour that transcends the cultural idealism of the early digital labour debate and some positions within the cultural industries school. On the one hand Williams refutes the separation of culture and the economy as well as base and superstructure. On the other hand he maintains that culture, as a signifying system, is a distinct system of society. How can we make sense of these claims that at first sight seem to be mutually exclusive? If one thinks dialectically, then a concept of culture as material and necessarily economic and at the same time distinct from the economy is feasible: culture and politics are dialectical sublations (Aufhebung) of the economy. In Hegelian philosophy sublation means that a system or phenomenon is preserved, eliminated, and lifted up. Culture is not the same as the economy, it is more than the sum of various acts of labour, it has emergent qualities— it communicates meanings in society—that cannot be found in the economy alone. But at the same time, the economy is preserved in culture: culture is not independent from labour, production and physicality, but requires and incorporates all of them.

Wolfgang Hofkirchner has introduced stage models as a way for philosophically conceptualizing the logic connections between different levels of organization. In a stage model, “one step taken by a system in question—that produces a layer—depends on the stage taken prior to that but cannot be reversed! […] layers—that are produced by steps—build upon layers below them but cannot be reduced to them!” (Hofkirchner 2013, 123f). Emergence is the foundational principle of a stage model (Hofkirchner 2013, 115): a specific level of organization of matter has emergent qualities so that the systems organized on this level are more than the sum of their parts, to which they cannot be reduced. An organization level has new qualities that are grounded in the underlying systems and levels that are preserved on the upper level and through synergies produce new qualities of the upper level. In the language of dialectical philosophy this means that the emergent quality of an organization level is a sublation (Aufhebung) of the underlying level.

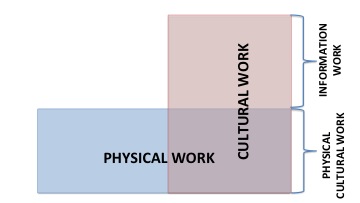

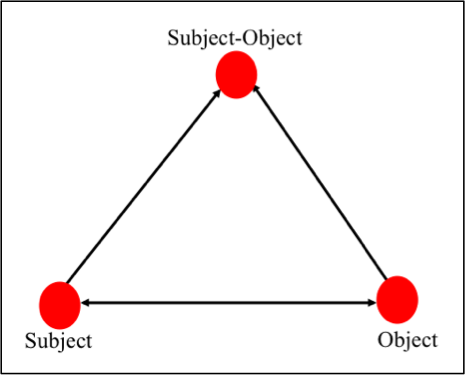

Figure 1: A stage model of cultural work

Using a stage model allows us to identify and relate different levels of cultural and digital work (see figure 1). Cultural work is a term that encompasses organisational levels of work that are at the same time distinct and dialectically connected: cultural work has an emergent quality, namely information work that creates content, that is based on and grounded in physical cultural work, which creates information technologies through agricultural and industrial work processes. Physical work takes place inside and outside of culture: it creates information technologies and its components (cultural physical work) as well as other products (non-cultural physical work) that do not primarily have symbolic functions in society (such as cars, tooth brushes or cups). Cars, toothbrushes, or cups do not primarily have the role of informing others or communicating with others, but rather help humans achieve the tasks of transport, cleanliness and nutrition. Culture and information work however feedback on these products and create symbolic meanings used by companies for marketing them. Cultural work is a unity of physical cultural work and information work that interact with each other, are connected and at the same time distinct.

The production of meaning, social norms, morals, and the communication of meanings, norms, and morals are work processes: they create cultural use-values. Culture requires on the one hand human creativity for creating cultural content and on the other hand specific forms and media for storage and communication. Work that creates information and communication through language is specific for work conducted in the cultural system: informational and communication work. For having social effects in society, information, and communication are organized (stored, processed, transported, analysed, transformed, created) with the help of information and communication technologies, such as computers, TV, radio, newspapers, books, recorded films, recorded music, language, etc. These technologies are produced by physical cultural work. Culture encompasses a) physical and informational work that create cultural technologies (information and communication technologies) and b) information work that creates information and communication.

These two types of work act together in order to produce and reproduce culture. Meanings and judgements are emergent qualities of culture that are created by informational work, they take on relative autonomy that has effects inside but also outside the economic system. This means that specific forms of work create culture, but culture cannot be reduced to the economy—it has emergent qualities.

Following Williams, communication is the “passing of ideas, information, and attitudes from person to person”, whereas communications means the “institutions and forms in which ideas, information, and attitudes are transmitted and received” (Williams 1962, 9). Information and communication are meaning-making activities created by informational work. Physical cultural work creates communications as institutions and forms that organize the creation and passing of information in social processes.

Marx identified two forms of information work: The first results in cultural goods that “exist separately from the producer, i.e. they can circulate in the interval between production and consumption as commodities, e.g. books, paintings and all products of art as distinct from the artistic achievement of the practising artist”. In the second, “the product is not separable from the act of producing” (Marx 1867, 1047f). The first requires a form, institution or technology that stores and transports information, as in the case of computer-mediated communication, the second uses language as main medium (e.g. theatre). The first requires physical cultural work for organizing storage, organization, and transport of information; the second is possible based only on information work.

Given the notion of cultural labour and a cultural-materialist framework inspired by Raymond Williams, we can next ask the question what is specific about the digital mode of cultural labour.

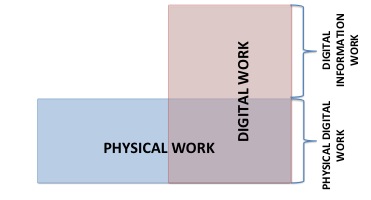

1.4. Digital Work and Digital Labour

The realm of digital media is a specific subsystem of the cultural industries and of cultural labour. Digital labour is a specific form of cultural labour that has to do with the production and productive consumption of digital media. There are other forms of cultural labour that are non-digital. Think for example of a classical music or rock concert. But these forms of live entertainment that are specific types of cultural labour also do not exist independently from the digital realm: Artists publish their recordings in digital format on iTunes, Spotify, and similar online platforms. Fans bring their mobile phones for taking pictures and recording concert excerpts that they share on social media platforms. There is little cultural labour that is fully independent from the digital realm today. The notion of digital work and digital labour wants to signify those forms of cultural labour that contribute to the existence of digital technologies and digital content. It is a specific form of cultural labour. Figure 2 applies the stage model of cultural work (see figure 1 above) to digital work.

Figure 2: A stage model of digital work

If culture were merely symbolic, mind, spirit, “immaterial”, superstructural, informational, a world of ideas, then digital labour as expression of culture clearly would exclude the concrete works of mining and hardware assemblage that are required for producing digital media. Williams’ Cultural Materialism, contrary to the position of Cultural Idealism, makes it possible to argue that digital labour includes both the creation of physical products and information that are required for the production and usage of digital technologies. Some digital workers create hardware, others hardware components, minerals, software or content that are all objectified in or the outcome of the application of digital technologies. Some workers, e.g. miners, not just contribute to the emergence of digital media, but to different products. If one knows the mines’ sales, then it is possible to determine to which extent the performed labour is digital or other labour.

In order to illustrate this point that culture is material, we now want return in greater detail to a passage where Marx reflects about the work of making and playing the piano. Marx wrote:

Productive labour is only that which produces capital. Is it not crazy, asks e.g. (or at least something similar) Mr Senior, that the piano maker is a productive worker, but not the piano player, although obviously the piano would be absurd without the piano player? But this is exactly the case. The piano maker reproduces capital; the pianist only exchanges his labour for revenue. But doesn't the pianist produce music and satisfy our musical ear, does he not even to a certain extent produce the latter? He does indeed: his labour produces something; but that does not make it productive labour in the economic sense; no more than the labour of the madman who produces delusions is productive. Labour becomes productive only by producing its own opposite (Marx 1857/58, 305).

Williams remarks that today, other than in Marx’s time, “the production of music (and not just its instruments) is an important branch of capitalist production” (Williams 1977, 93).

If the economy and culture are two separate realms, then building the piano is work and part of the economy and playing it is not work, but culture. Marx leaves however no doubt that playing the piano produces a use-value that satisfies human ears and is therefore a form of work. As a consequence, the production of music must just like the production of the piano be an economic activity. Williams (1977, 94) stresses that cultural materialism means to see the material character of art, ideas, aesthetics and ideology and that when considering piano making and piano playing it is important to discover and describe “relations between all these practices” and to not assume “that only some of them are material”.

Apart from the piano maker and the piano player there is also the composer of music. All three forms of work are needed and necessarily related in order to guarantee the existence of piano music. Fixing one of these three productive activities categorically as culture and excluding the others from it limits the concept of culture and does not see that one cannot exist without the other. Along with this separation come political assessments of the separated entities. A frequent procedure is to include the work of the composer and player and to exclude the work of the piano maker. Cultural elitists then argue that only the composer and player are truly creative, whereas vulgar materialists hold that only the piano maker can be a productive worker because he works with his hands and produces an artefact. Both judgments are isolationist and politically problematic.

Taking the example of piano music and transferring it to digital media, we find correspondences: Just like we find piano makers, music composers and piano players in the music industry, we find labour involved in hardware production (makers), content and software production (composers) and productive users (prosumers, players, play labour) in the world of digital labour. In the realm of digital labour, we have to emphasize that practices are “from the beginning social and material” (Williams 1989, 206).

There is a difference if piano makers, players and music composers do so just as a hobby or for creating commodities that are sold on the market. This distinction can be explored based on Marx’s distinction between work (Werktätigkeit) and labour (Arbeit): Brigitte Weingart (1997) describes the origins of the terms work in English and Arbeit and Werk in German: In German, the word Arbeit comes from the Germanic term arba, which meant slave. The English term work comes from the Middle English term weorc. It was a fusion of the Old English terms wyrcan (creating) and wircan (to affect something). So to work means to create something that brings about some changes in society. Weorc is related to the German terms Werk and werken. Both work in English and Werk in German were derived from the Indo-European term uerg (doing, acting). Werken in German is a term still used today for creating something. Its origins are quite opposed to the origins of the term Arbeit. The result of the process of werken is called Werk. Both werken and Werk have the connotative meaning of being creative. Both terms have an inherent connotation of artistic creation. Arendt (1958, 80f) confirms the etymological distinction between ergazesthai (Greek)/facere, fabricari (Latin)/work (English)/werken (German)/ouvrer (French) and ponein (Greek)/laborare (Latin)/labour (English)/arbeiten (German)/travailler (French).

Raymond Williams (1983, 176–179) argues that the word “labour” comes from the French word labor and the Latin term laborem and appeared in the English language first around 1300. It was associated with hard work, pain and trouble. In the 18th century, it would have attained the meaning of work under capitalist conditions that stands in a class relationship with capital. The term “work” comes from the Old English word weorc and is the “most general word for doing something” (ibid, 334). In capitalism the term on the one hand has, according to Williams (ibid, 334–337), acquired the same meaning as labour—a paid job—but would have in contrast also kept its original broader meaning. In order to be able to differentiate the dual historical and essential character of work, it is feasible to make a semantic differentiation between labour and work.

Figure 3: The etymology of the terms work, labour and Arbeit

The meaning and usage of words develops historically and may reflect the structures and changes of society, culture and the economy. Given that we find an etymological distinction between the general aspects of productive human activities and the specific characteristics that reflect the realities of class societies, it makes sense to categorically distinguish between the anthropological dimension of human creative and productive activities that result in use-values that satisfy human needs and the historical dimension that describes how these activities are embedded into class relations (Fuchs 2014a). A model of the general work process is visualized in figure 4.

Figure 4: The general work process

Human subjects have labour power. Their labour in the work process interacts with the means of production (object). The means of production consist of the object of labour (resources, raw materials) and the instruments of labour (technology). In the work process, humans transform an object (nature, culture) by making use of their labour power with the help of instruments of labour. The result is a product that unites the objectified labour of the subject with the objective materials s/he works on. Work becomes objectified in a product and the object is as a result transformed into a use value that serves human needs. The productive forces are a system, in which subjective productive forces (human labour power) make use of technical productive forces (part of the objective productive forces) in order to transform parts of the nature/culture so that a product emerges.

The general work process is an anthropological model of work under all historical conditions. The connection of the human subject to other subjects in figure 4 indicates that work is normally not conducted individually, but in relations with others. A society could hardly exist based on isolated people trying to sustain themselves independently. It requires economic relations in the form of co-operation and a social organization of production, distribution and consumption. This means that work takes place under specific historical social relations of production. There are different possibilities for the organization of the relations of production. In general the term labour points towards the organization of labour under class relations, i.e. power relationships that determine that any or some of the elements in the work process are not controlled by the workers themselves, but by a group of economic controllers. Labour designates specific organization forms of work, in which the human subject does not control his/her labour power (she is compelled to work for others) and/or there is a lack of control of the objects of labour and/or the instruments of labour and/or the products of labour.

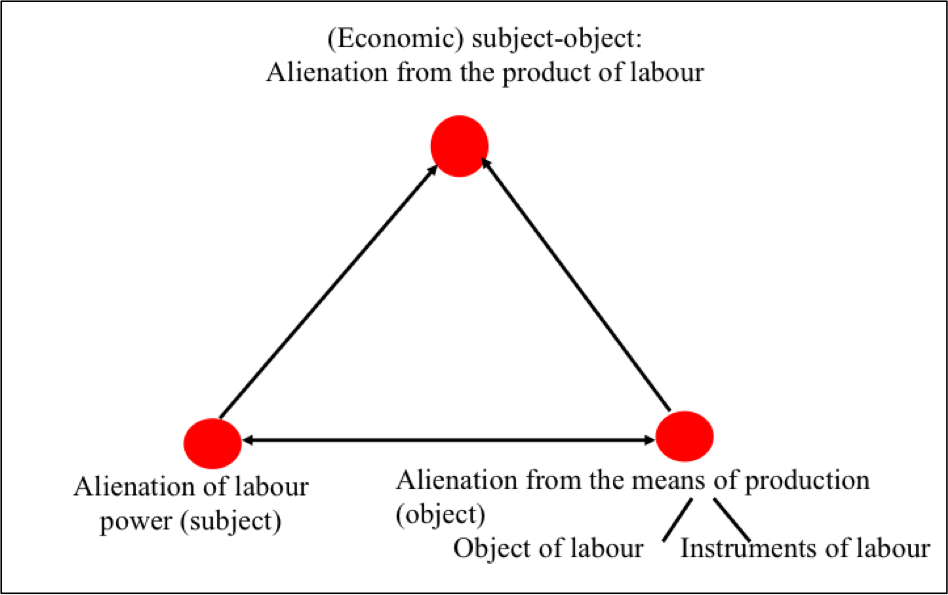

Karl Marx pinpoints this lack of control by the term alienation and understands the unity of these forms of alienation as exploitation of labour: “The material on which it [labour] works is alien material; the instrument is likewise an alien instrument; its labour appears as a mere accessory to their substance and hence objectifies itself in things not belonging to it. Indeed, living labour itself appears as alien vis-à-vis living labour capacity, whose labour it is, whose own life’s expression it is, for it has been surrendered to capital in exchange for objectified labour, for the product of labour itself. […] labour capacity’s own labour is as alien to it – and it really is, as regards its direction etc.—as are material and instrument. Which is why the product then appears to it as a combination of alien material, alien instrument and alien labour—as alien property” (Marx 1857/58, 462). Figure 5 visualizes potential dimensions of the labour process as alienated work process.

Figure 5: Labour as alienated work process

Given these preliminary assumptions about the work-labour distinction and cultural materialism, one can provide a definition of digital work and digital labour:

Digital work is a specific form of work that makes use of the body, mind or machines or a combination of all or some of these elements as an instrument of work in order to organize nature, resources extracted from nature, or culture and human experiences, in such a way that digital media are produced and used. The products of digital work are depending on the type of work: minerals, components, digital media tools or digitally mediated symbolic representations, social relations, artefacts, social systems and communities. Digital work includes all activities that create use-values that are objectified in digital media technologies, contents and products generated by applying digital media” (Fuchs 2014a, 352).

Digital labour is alienated digital work: it is alienated from itself, from the instruments and objects of labour and from the products of labour. Alienation is alienation of the subject from itself (labour-power is put to use for and is controlled by capital), alienation from the object (the objects of labour and the instruments of labour) and the subject-object (the products of labour). Digital work and digital labour are broad categories that involve all activities in the production of digital media technologies and contents. This means that in the capitalist media industry, different forms of alienation and exploitation can be encountered. Examples are slave workers in mineral extraction, Taylorist hardware assemblers, software engineers, professional online content creators (e.g. online journalists), call centre agents and social media prosumers” (Fuchs 2014a, 351f).

Work and labour are not isolated individual activities, but take place as part of social relations and larger modes of how the economy is organised. The concepts of digital work and digital labour need therefore to be related to a concept that can describe the organisational structure of the economy. One such concept is Marx’s notion of the mode of production.

2. Digital Labour and Modes of Production

Michael Porter (1985) introduced the notion of the value chain that he defined as “a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver and support its product” (Porter 1985, 36). The term value chain has become a popular category for analysing the organisation of capital, which is indicated by the circumstance that 11 682 articles indexed in the academic database Business Source Premier use the term in their abstract (accessed on May 21, 2013). The term has also been used in mainstream media economics for analysing the value chains of traditional media and ICTs (see Zerdick et al. 2000, 126-135). The problem of the mainstream use of the concept of the value chain is that it focuses on the stages in commodity production and tends to neglect aspects of working conditions and class relations. Also critical scholars have used the notion of the global value chain (see for example: Huws 2008, Huws and Dahlmann 2010).

An alternative concept that was introduced by critical studies is the notion of the new international division of labour (NIDL):

The development of the world economy has increasingly created conditions (forcing the development of the new international division of labour) in which the survival of more and more companies can only be assured through the relocation of production to new industrial sites, where labour-power is cheap to buy, abundant and well-disciplined; in short, through the transnational reorganization of production (Fröbel, Heinrichs and Kreye 1981, 15).

A further development is that “commodity production is being increasingly subdivided into fragments which can be assigned to whichever part of the world can provide the most profitable combination of capital and labour” (Fröbel, Heinrichs and Kreye 1981, 14). In critical media and cultural studies, Miller et al. (2004) have used this concept for explaining the international division of cultural labour (NICL). The concept of the NIDL has the advantage that it stresses the class relationship between capital and labour and how in processes of class struggle capital tries to increase profits by decreasing its overall wage costs via the global diffusion of the production process. It is also a concept that encompasses workers’ struggles against the negative effects of capitalist restructuring.

The approach taken in this paper stands in the Marxist tradition that stresses class contradictions in the analysis of globalisation. It explores how the notion of the mode of production can be connected to the concept of the new international division of labour. The notion of the mode of production stresses a dialectical interconnection of on the one hand class relationships (relations of production) and on the other hand the forms of organisation of capital, labour and technology (productive forces). The class relationship is a social relationship that determines who owns private property and has the power to make others produce surplus-value that they do not own and that is appropriated by private property owners. Class relationships involve an owning class and a non-owing class: the non-owning class is compelled to produce surplus value that is appropriated by the owning class.

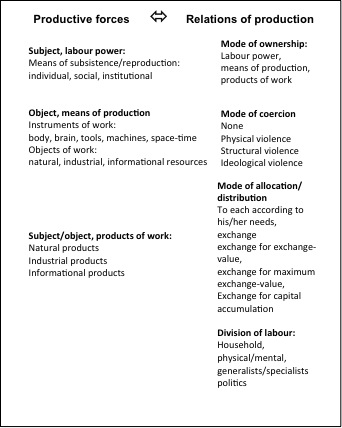

The relations of production determine the property relations (who owns which share (full, some, none) of labour power, the means of production, products of labour), the mode of allocation and distribution of goods, the mode of coercion used for defending property relations and the division of labour. Class relationships are forms of organization of the relations of production, in which a dominant class controls the modes of ownership, distribution and coercion for exploiting a subordinated class. In a classless society human control ownership and distribution in common.

Every economy produces a certain amount of goods per year. Specific resources are invested and there is a specific output. If there is no contraction of the economy due to a crisis, then a surplus product is created, i.e. an excess over the initial resources. The property relations determine who owns the economy’s initial resources and surplus. Table 2 (see further below) distinguishes modes of production (patriarchy, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, communism) based on various modes of ownership, i.e. property relations.

The mode of allocation and distribution defines how products are distributed and allocated: In a communist society, each person gets whatever s/he requires to survive and satisfy human needs. In class societies, distribution is organized in the form of exchange: exchange means that one product is exchanged for another. If you have nothing to exchange because you own nothing, then you cannot get hold of other goods and services, except those that are not exchanged, but provided for free. There are different forms how exchange can be organized: general exchange, exchange for exchange-value (x commodity A = y commodity B), exchange for maximum exchange-value, exchange for capital accumulation.

The mode of coercion takes on the form of physical violence (overseers, security forces, military), structural violence (markets, institutionalised wage labour contracts, legal protection of private property, etc) and cultural violence (ideologies that present the existing order as the best possible or only possible order and try to defer the causes of societal problems by scapegoating). In a free society no mode of coercion is needed.

The division of labour defines who conducts which activities in the household, the economy, politics and culture. Historically there has been a gender division of labour, a division between mental and physical work, a division into many different functions conducted by specialists and an international division of labour that is due to the globalization of production. Marx in contrast imagined a society of generalists that overcomes the divisions of labour so that society is based on well-rounded universally active humans (Marx 1867, 334-335). Marx (1857/58, 238) says that in class society “labour will create alien property and property will command alien labour”. The historical alternative is a communist society and mode of production, in which class relationships are dissolved and the surplus product and private property are owned and controlled in common.

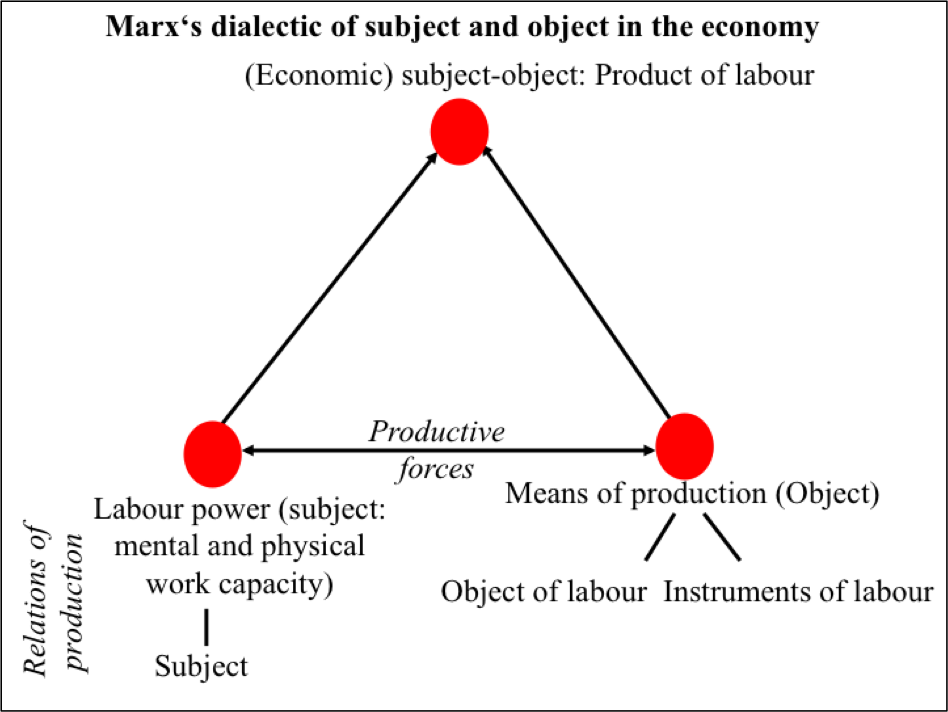

The relations of production are dialectically connected to the system of the productive forces (see figure 3 in section 1 of this paper): human subjects have labour power that in the labour process interacts with the means of production (object). The means of production consist of the object of labour (natural resources, raw materials) and the instruments of labour (technology). In the labour process, humans transform the object of labour (nature, culture) by making use of their labour power with the help of instruments of labour. The result is a product of labour, which is a Hegelian subject-object, or, as Marx says, a product, in which labour has become bound up in its object: labour is objectified in the product and the object is as a result transformed into a use value that serves human needs. The productive forces are a system, in which subjective productive forces (human labour power) make use of technical productive forces (part of the objective productive forces) in order to transform parts of the natural productive forces (which are also part of the objective productive forces) so that a labour product emerges. One goal of the development of the system of productive forces is to increase the productivity of labour, i.e. the output (amount of products) that labour generates per unit of time. Marx (1867, 431) spoke in this context of the development of the productive forces. Another goal of the development of the productive forces can be the enhancement of human self-development by reducing necessary labour time and hard work (toil).

In Capital, Marx (1867) makes a threefold distinction between labour-power, the object of labour and the instruments of labour: “The simple elements of the labour process are (1) purposeful activity, (2) the object on which that work is performed, and (3) the instruments of that work” (284). Marx’s discussion of the production process can be presented in a systematic way by using Hegel’s concept of the dialectic of subject and object. Hegel (1991) has spoken of a dialectical relation of subject and object: the existence of a producing subject is based on an external objective environment that enables and constrains (i.e. conditions) human existence. Human activities can transform the external (social, cultural, economic, political, natural) environment. As a result of the interaction of subject and object, new reality is created—Hegel terms the result of this interaction “subject-object”. Figure 5 shows that Hegel’s notion of subject, object, and subject-object form a dialectical triangle.

Hegel (1991) characterizes the “subjective concept” as formal notion (§162), a finite determination of understanding a general notion (§162), “altogether concrete” (§164). He defines “the subject” as “the posited unseparatedness of the moments in their distinction” (§164). Hegel characterizes objectivity as totality (§193),“external objectivity”(§208),“external to an other” (§193),“the objective world in general” that “falls apart inwardly into [an] undetermined manifoldness” (§193), “immediate being” (§194), “indifference vis-à-vis the distinction” (§194), “realisation of purpose” (§194), “purposive activity” (§206) and “the means” (§206).The Idea is “the Subject-Object” (§162), absolute Truth (§162), the unity of the subjective and the objective (§212), “the absolute unity of Concept and objectivity” (§213), “the Subject-Object” understood as “the unity of the ideal and the real, of the finite and the infinite, of the soul and the body” (§214). Hegel also says that the “Idea is essentially process” (§215). Marx applied Hegel’s dialectic of subject and object on a more concrete level to the economy in order to explain how the process of economic production works as an interconnection of a subject (labour power) and an object (objects and instruments) so that a subject-object (product) emerges (see figure 6).

Figure 6: Hegel’s dialectic of subject and object

The instruments of work can be the human brain and body, mechanical tools and complex machine systems. They also include specific organizations of space-time, i.e. locations of production that are operated at specific time periods. The most important aspect of time is the necessary work time that depends on the level of productivity. It is the work time that is needed per year for guaranteeing the survival of a society. The objects and products of work can be natural, industrial or informational resources or a combination thereof.

The productive forces are a system of production that creates use-values. There are different modes of organization of the productive forces, such as agricultural productive forces, industrial productive forces and informational productive forces. Table 1 gives an overview.

|

Mode |

Instruments of work |

Objects of work |

Products of work |

|

Agricultural productive forces |

Body, brain, tools, machines |

Nature |

Basic products |

|

Industrial productive forces |

Body, brain, tools, machines |

Basic products, industrial products |

Industrial products |

|

Informational productive forces |

Body, brain, tools, machines |

Experiences, ideas |

Informational products |

Table 1. Three Modes of Organization of the Productive Forces

Figure 7 shows dimensions of the relations of production and the productive forces.

Figure 7: Dimensions of the Productive Forces and the Relations of Production

Classical slavery, serfdom and wage labour are three important historical forms of class relations that are at the heart of specific modes of production (Engels 1884). Marx and Engels argue that private property and slavery have their origin in the family: The first historical form of private property can be found in the patriarchal family (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 52). The family is a mode of production, in which labour power is no commodity, but organised by personal and emotional relationships that result in commitment that includes family work that is unremunerated and produces affects, social relations and the reproduction of the human mind and body. It can therefore also be called reproductive work.

A wage worker’s labour power has a price, its wage, whereas a slave’s labour power does not have a price—it is not a commodity. However, the slave him-/herself has a price, which means that its entire human body and mind can be sold as a commodity from one slave owner to another, who then commands the entire life time of the slave (Marx, 1857/58: 288–289). The slave in both ancient slavery and feudalism is treated like a thing and has the status of a thing (Marx 1857/58, 464–465).

In the Grundrisse’s section “Forms which precede capitalist production“ (Marx 1857/58, 471–514) as well as in the German Ideology’s section “Feuerbach: Opposition of the materialist and idealist outlooks“ (Marx and Engels 1845/46), Marx discusses the following modes of production:

- The tribal community based on the patriarchal family;

- Ancient communal property in cities (Rome, Greece);

- Feudal production in the countryside;

- Capitalism.

Table 2 provides a classification of modes of production based on the dominant forms of ownership (self-control, partly self-control and partly alien control, full alien control)

|

|

Owner of labour power |

Owner of the means of production |

Owner of the products of work |

|

Patriarchy |

Patriarch |

Patriarch |

Family |

|

Slavery |

Slavemaster |

Slavemaster |

Slavemaster |

|

Feudalism |

Partly self-control, partly lord |

Partly self-control, partly lord |

Partly self-control, partly lord |

|

Capitalism |

Worker |

Capitalist |

Capitalist |

|

Communism |

Self |

All |

Partly all, partly individual |

Table 2: The main forms of ownership in various modes of production

But how are modes of production related to each other? In a historical way, where they supersede each other, or in a historical-logical way within a specific social formation that sublates older formations but encompasses older modes of production into itself? Jairus Banaji (2011) argues that Stalinism and vulgar Marxism have conceptualised the notion of the mode of production based on the assumption that a specific mode contains only one specific historical form of labour and surplus-value appropriation and eliminates previous modes so that history develops in the form of a linear evolution: slavery à feudalism à capitalism à communism. So for example Althusser and Balibar (1970) argue that the historical development of society is non-dialectical and does not involve sublations, but rather transitions “from one mode of production to another” (Althusser and Balibar 1970, 307) so that one mode succeeds the other. This concept of history is one of the reasons why E.P. Thompson (1978, 131) has characterized Althusser’s approach as “Stalinism at the level of theory”. The Stalinist “metaphysical-scholastic formalism” (Banaji 2011, 61) has been reproduced in liberal theory’s assumption that there is an evolutionary historical development from the agricultural society to the industrial society to the information society so that each stage eliminates the previous one (as argued by: Bell 1974; Toffler 1980), which shows that in the realm of theory some liberals of today share in their theory elements of Stalinism. According to Banaji, capitalism often intensified feudal or semi feudal production relations. In parts of Europe and outside, feudalism would have only developed as a “commodity-producing enterprise” (Banaji 2011, 88). In the Islamic world capitalism would have developed without slavery and feudalism (Banaji 2011, 6).

Banaji advances in contrast to formalist interpretations a complex reading of Marx’s theory, in which a mode of production is “capable of subsuming often much earlier forms” (Banaji 2011, 1), “similar forms of labour-use can be found in very different modes of production” (6), capitalism is “working through a multiplicity of forms of exploitation” (145) and is a combined form of development (358) that integrates “diverse forms of exploitation and ways of organising labour in its drive to produce surplus value” (359).

A mode of production is a unity of productive forces and relations of production (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 91). If these modes are based on classes as their relations of production, then they have specific contradictions that can via class struggles result in the sublation (Aufhebung) of one mode of production and the emergence of a new one. The emergence of a new mode of production does not necessarily abolish, but rather sublate (aufheben) older modes of production. This means that history is for Marx a dialectical process precisely in Hegel’s threefold meaning of the term Aufhebung (sublation): 1) uplifting, 2) elimination, 3) preservation: 1) There are new qualities of the economy, 2) the dominance of an older mode of production vanishes, 3) but this older mode continues to exist in the new mode in a specific form and relation to the new mode. The rise of e.g. capitalism however did not bring an end to patriarchy, but the latter continued to exist in such a way that a specific household economy emerged that fulfils the role of the reproduction of modern labour power. A sublation can be more or less fundamental. A transition from capitalism to communism requires a fundamental elimination of capitalism, the question is however if this is immediately possible. Elimination and preservation can take place to differing degrees. A sublation is also no linear progression. It is always possible that relations that resemble earlier modes of organization are created.

Capitalism is at the level of the relations of production organised around relations between capital owners on the one side and paid/unpaid labour and the unemployed on the other side. On the level of the productive forces, it has developed from industrial to informational productive forces. The informational productive forces do not eliminate, but sublate (aufheben) other productive forces (Adorno 1968/2003, Fuchs 2014a, chapter 5): in order for informational products to exist a lot of physical production is needed, which includes agricultural production, mining and industrial production. The emergence of informational capitalism has not virtualised production or made it weightless or immaterial, but is grounded in physical production (Huws 1999, Maxwell and Miller 2012). Whereas capitalism is a mode of production, the terms agricultural society, industrial society and information society characterise specific forms of the organisation of the productive forces (Adorno 1968/2003; Fuchs 2014a, chapter 5).

The new international division of labour (NIDL) organises the labour process in space and time in such a way that specific components of the overall commodity are produced in specific spaces in the global economy and are reassembled in order to form a coherent whole that is sold as a commodity. It thereby can command labour on the whole globe and during the whole day. The approach taken by the authors of this paper advocates a broad understanding of digital labour based on an industry rather than an occupation definition in order to stress the commonality of exploitation, capital as the common enemy of a broad range of workers and the need to globalize and network struggles in order to overcome the rule of capitalism. Some of the workers described in this article are not just exploited by digital media capital, but also and sometimes simultaneously by other forms of capital. It is then a matter of degree to which extent these forms of labour are digital labour and simultaneously other forms of labour. If we imagine a company with job rotation so that each worker on average assembles laptops for 50% of his/her work time and cars for the other half of the time, a worker in this factory is a digital worker for 50%. S/he is however an industrial worker for 100% because the content of both manufacturing activities is the industrial assemblage of components into commodities. The different forms of digital labour are connected in an international division of digital labour (IDDL), in which all labour necessary for the existence, usage and application of digital media is “disconnected, isolated […], carried on side by side” and ossified “into a systematic division” (Marx 1867, 456).

Given a model of the mode of production, the question arises how one can best analyze the working conditions in a specific company, industry or sector of the economy when conducting a labour process and class analysis. Which dimensions of labour have to be taken into account in such an analysis? The next section will address this question.

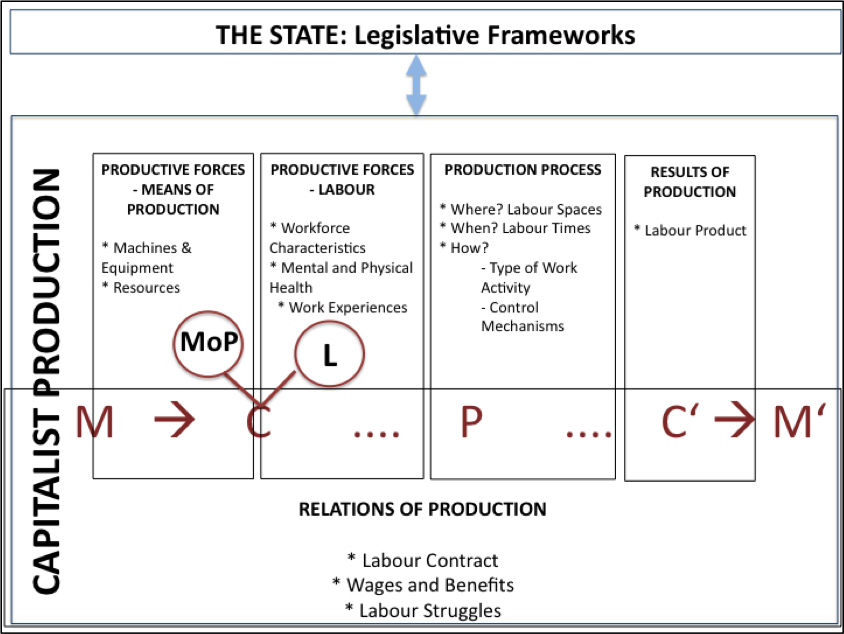

3. A Typology of the Dimensions of Working Conditions

A suitable starting point for a systematic model of different dimensions of working conditions is the circuit of capital accumulation as Karl Marx described it (1867, 248-253; 1885, 109). According to Marx, capital accumulation in a first stage requires the investment of capital in order to buy what is necessary for producing commodities, the productive forces: labour time of workers (L or variable capital) on the one hand, and working equipment like machines and raw materials (MoP or constant capital) on the other hand (Marx 1885/1992, 110). Thus, money (M) is used in order to buy labour power as well as machines and resources as commodities (C) that then in a second stage enter the labour process and produce (P) a new commodity (C’) (Marx 1885, 118). This new commodity (C’) contains more value than the sum of its parts, i.e. surplus value. This surplus value needs to be realized and turned into more money (M’) by selling the commodity in the market (Marx 1885/1992, 125). The circuit of capital accumulation can thus be described with the following formula:

M -> C … P … C’ -> M’ (Marx 1885, 110).

According to Marx, surplus value can only be generated due to the specific qualities of labour-power as a commodity. Marx argued that labour power is the only commodity “whose use-value possesses the peculiar property of being a source of value, whose actual consumption is therefore itself an objectification of labour, hence a creation of value” (Marx 1867, 270).

Labour is thus essential to the process of capital accumulation. The model in figure 7 takes the labour process as its point of departure for identifying different dimensions that shape working conditions (Sandoval 2013). The purpose of this model is to provide comprehensive guidelines that can be applied for systematically studying working conditions in different sectors (for a systematic study of corporate irresponsibility of working and production conditions in 8 companies in the media industries see Sandoval 2014).

Figure 8: Dimensions of working conditions

The model pictured in figure 8 identifies five areas that shape working conditions throughout the capital accumulation process: means of production, labour, relations of production, the production process and the outcome of production. Furthermore this model includes the state’s impact on working conditions through labour legislation:

Productive Forces—Means of Production: Means of production include machines and equipment on the one hand and resources that are needed for production on the other hand. The question whether workers operate big machines, work at the assembly line, use mobile devices such as laptops, handle potentially hazardous substances, use high-tech equipment, traditional tools or no technology at all etc. shapes the experience of work and has a strong impact on work processes and working conditions.

Productive Forces—Labour: The subjects of the labour process are workers themselves. One dimension that impacts work in a certain sector is the question how the workforce is composed in terms of gender, ethnic background, age, education levels etc. Another question concerns worker health and safety and how it is affected by the means of production, the relations of production, the labour process, and labour law. Apart from outside impacts on the worker, an important factor is how workers themselves experience their working conditions.

Relations of Production: Within capitalist relations of production, capitalists buy labour power as a commodity. Thereby a relation between capital and labour is established. The purchase of labour power is expressed through wages. Wages are the primary means of subsistence for workers and the reason why they enter a wage labour relation. The level of wages thus is a central element of working conditions. Labour contracts specify the conditions under which capital and labour enter this relation, including working hours, wages, work roles and responsibilities etc. The content of this contract is subject to negotiations and often struggles between capital and labour. The relation between capital and labour is thus established through a wage relation and formally enacted by a labour contract that is subject to negotiations and struggles. These three dimensions of the relation between capital and labour set the framework for the capitalist labour process.

Production process: Assessing working conditions, furthermore, requires looking at the specifics of the actual production process. A first factor in this context is its spatial location. Whether it is attached to a certain place or is location independent, whether it takes place in a factory, an office building, or outdoors etc. are important questions. A second factor relates to the temporal dimension of work. Relevant questions concern the amount of regular working hours and overtime, work rhythms, the flexibility or rigidness of working hours, the relation between work time and free time etc. Finally working conditions are essentially shaped by how the production process is executed. This includes on the one hand the question which types of work activity are performed. The activities can range from intellectual work, to physical work, to service work, from skilled to unskilled work, from creative work to monotonous and standardized work tasks, etc. On the other hand another aspect of the production process is how it is controlled and managed. Different management styles can range from strict control of worker behaviour and the labour process to high degrees of autonomy, self-management or participatory management etc. Space, time, activity and control are essential qualities of the production process and therefore need to be considered when studying working conditions.

Product: Throughout the production process workers put their time, effort and energy into producing a certain product. This actual outcome of production and how it relates back to the worker thus needs to be considered for understanding work in a certain sector.

The state: Finally the state has an impact on working conditions through enacting labour laws that regulate minimum wages, maximum working hours, social security, safety standards etc.

Table 3 summarizes the dimensions of working conditions that we described above.

|

Productive forces—Means of production |

Machines and equipment |

Which technology is being used during the production process? |

|

Resources |

What resources are used during the production process? |

|

|

Productive forces—Labour |

Workforce characteristics |

What are important characteristics of the workforce for example in terms of age, gender, ethnic background etc? |

|

Mental and physical health |

How do the employed means of production and the labour process impact mental and physical health of workers? |

|

|

Work experiences |

How do workers experience their working conditions? |

|

|

Relations of production |

Labour contracts |

Which type of contracts do workers receive, what do they regulate? |

|

Wages and benefits |

How high/low are wage levels and what are other material benefits for workers? |

|

|

Labour struggles |

How do workers organize and engage in negotiations with capital and what is the role of worker protests? |

|

|

Production process |

Labour spaces |

Where does the production process take place? |

|

Labour times |

How many working hours are common within a certain sector, how are they enforced and how is the relationship between work and free time? |

|

|

Work activity |

Which type of mental and/or physical activity are workers performing? |

|

|

Control mechanism |

Which type of mechanisms are in place that control the behaviour of workers? |

|

|

Results of production |

Labour product |

Which kinds of products or services are being produced? |

|

The state |

Labour law |

Which regulations regarding minimum wages, maximum working hours, safety, social security etc are in place and how are they enforced? |

Table 3: Dimensions of working conditions

Given an identification of dimensions of working conditions, we can next bring this typology together with aspects of digital labour.

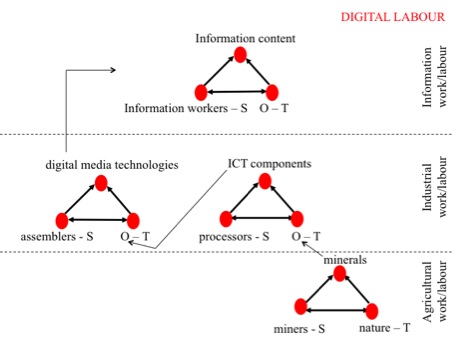

4. The Conditions of Digital Labour

In section 1, we introduced a cultural-materialist model of cultural work (figure 1) that distinguishes between physical cultural work and information work. Figure 8 is an application of this model to the realm of digital labour: digital labour is a special form of cultural work that results in the production and use of digital media. It distinguishes three forms of digital labour that represent different modes of the organisation of the productive forces: agricultural digital labour, industrial digital labour, informational digital labour. They are articulations of the three organisation forms of the productive forces that we identified in table 1: agricultural, industrial and informational productive forces. Agricultural and industrial digital work/labour are forms of physical cultural work/labour in the context of digital media. Informational digital work/labour is an expression of information work in the realm of digital media production.

Figure 9 shows a model of the major production processes that are involved in digital labour. Each production step/labour process involves human subjects (S) using technologies/instruments of labour (T) on objects of labour (O) so that a product emerges. The very foundation of digital labour is an agricultural labour cycle in which miners extract minerals. These minerals enter the next production process as objects so that processors based on them in physical labour processes create ICT components. These components enter the next labour cycle as objects: assemblage workers build digital media technologies and take ICT components as inputs. Processors and assemblers are industrial workers involved in digital production. The outcome of such labour are digital media technologies that enter various forms of information work as tools for the production, distribution, circulation, prosumption, and consumption of diverse types of information.

Figure 9: The complex network of cycles of digital labour

“Digital labour” is not a term that only describes the production of digital content. We rather use the term in a more general sense for the whole mode of digital production that contains a network of agricultural, industrial and informational forms of work that enables the existence and usage of digital media. The subjects involved in the digital mode of production (S)— miners, processors, assemblers, information workers and related workers—stand in specific relations of production that are either class relations or non-class relations. So what we designate as S in figure 8 is actually a relationship S1–S2 between different subjects or subject groups. In contemporary capitalist society, most of these digital relations of production tend to be shaped by wage labour, slave labour, unpaid labour, precarious labour, and freelance labour.

In section 2, we introduced a model of the work process in general (figures 4, 6, 7; tables 1, 2). Section 3 presented a model for the analysis of capitalist working conditions in capitalism (table 3, figure 8). How are these two models connected? The first one is more general and presents typologies for all modes of production (patriarchy, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, communism) and productive forces (agricultural, industrial, informational). The second model shown in figure 8 and table 3 shows dimension of labour within the capitalist mode of production. Table 4 shows how elements in model 1 (figure 4) correspond to elements in model 2 (figure 8, table 3).

|

MODEL 2 (figure 8, table 3) |

MODEL 1 (figure 4) |

|

|

Productive forces - Means of production |

Machines and equipment |

Object: Instruments of labour |

|

Resources |

Object: Object of labour |

|

|

Productive forces - Labour |

Workforce characteristics |

Subject |

|

Mental and physical health |

Subject |

|

|

Work experiences |

Subject |

|

|

Relations of production |

Labour contracts |

Subject-subject relationships: Relations of production |

|

Wages and benefits |

Subject-subject relationships: Relations of production |

|

|

Labour struggles |

Subject-subject relationships: Relations of production |

|

|

Production process |

Labour spaces |

Object: Instruments of labour |

|

Labour times |

Subject-subject relationships: Relations of production |

|

|

Work activity |

Subject |

|

|

Control mechanism |

Subject-subject relationships: Relations of production |

|

|

Results of production |

Labour product |

Subject-object: Products of labour |

|

The state |

Labour law |

Subject-subject relationships: Relations of production |

Table 4: Dimensions of working conditions

We have developed a systematic digital labour analysis toolkit that helps asking systematic questions about the involved labour processes. It can be applied to agricultural, industrial and informational digital labour and combinations of these forms of work. Table 5 presents the digital labour analysis toolkit that is based on the more general model introduced in table 3.

|

Productive forces - Means of production |

Machines and equipment |

What technologies or combinations thereof are being used during

the agricultural, industrial and informational production process that create

digital media and contents?

|

a) non-digital machines c) human brain |

|

Resources |

What resources or combinations thereof are used during the

agricultural, industrial and informational production processes of digital

media and content? |

a) physical resources: natural resources |

|

|

Productive forces—Labour |

Workforce characteristics |

What are important characteristics of the workforce in agricultural, industrial and informational digital labour (for example in terms of age, gender, ethnic background etc)? |

a) class |

|

Mental and physical health |

How do the employed means of production and the labour process impact mental and physical health of agricultural, industrial and informational digital workers? |

a) mental health |

|

|

Work experiences |

How do agricultural, industrial and informational digital workers experience their working conditions? |

|

|

|

Relations of production |

Labour contracts |

Are there labour contracts or not? In the case, where there are labour contracts: Which type of contracts do digital workers receive, what do they regulate? |

a) no contract, |

|

Wages and benefits |

Are there wages and specific benefits digital workers enjoy or not? In case, where there are wages and benefits: How high/low are wage levels and what are other material benefits for digital workers? |

a) wage level d) included/excluded unemployment insurance |

|

|

Labour struggles |

Is there the possibility that digital workers form associations (freedom of association)? If so, do such associations exist and what do they do? If so, how do digital workers organise and engage in negotiations with capital and what is the role of worker protests? |

a) yellow unions, |

|

|

Production process |

Labour spaces |

In which space or combination of spaces does the production

process take place? |

a) natural (e.g. mines, parks, etc) or human-built spaces (offices, factories, coffeehouse, homes etc) spaces, b) private, public or semi-public spaces, |

|

Labour times |

How many working hours are common within a certain sector, how are they enforced and how is the relationship between work and free time? |

a) legally unregulated or regulated working times, |

|

|

Work activity |

Which type of mental and/or physical activity or combinations thereof are digital workers performing? |

a) physical work: agricultural work |

|

|

Control mechanism |

Are there forms of control that benefit others at the expense of

workers? Which type of mechanisms are in place that control the behaviour of

workers? |

a) no control mechanism, e) social control by supervisors and mangers, |

|

|

Results of production |

Labour product |

Which kinds of products or services does digital labour produce? |

a) digital or non-digital products, |

|

The state |

Labour legislation |

Are there state laws that regulate work? Which regulations regarding minimum wages, maximum working hours, safety, social security etc are in place and how are they enforced? |

a) Regulation and enforcement of work and service contracts,

legal dispute resolution f) Employee representation and freedom of association, etc. |

Table 5: Digital labour analysis toolkit