“A Real China”: On User-Generated Videos – Audiovisual Narratives of Confucianism

Jacobs University Bremen, Germany, j.hao@jacobs-university.de

Abstract: Beneath the “Chinese success story,” social stratification, class polarization, and cultural displacement have increased dramatically. Can Confucian values contribute to dissolving the downsides of modernization in contemporary Chinese society? This paper investigates the current revival of Confucianism as a form of critique and a means of reconstructing of the Chinese socio-culture. Its data are user-generated videos. By means of a thematic audiovisual narrative analysis, the study is based on the material of 20 hours of Youku Paike videos uploaded between 2007 and 2013. The results are: (1) About one third of the user-generated videos can be interpreted as Confucian thematic narratives with a slightly increasing trend in portrayals of values of Confucian origin. (2) Under the circumstances of China’s present modernization and cyberization, Confucianism may be contributing to the formation of a new online socio-culture advocating social action and humanistic values.

Keywords: China, Confucianism, Cyberization, Audiovisual Narratives, Youku Paike Videos, Online Confucian Socio-Culture

Acknowledgements: Thanks are due to Peter Ludes, Professor of Mass Communication at Jacobs University Bremen, and to Dominic Sachsenmaier, Professor of Modern Asian History in said place, for their inspiring discussions on matters of critical theory, socio-culture and modernity in China.

Due to the recent three decades of phenomenal economic growth, China has undoubtedly become “a country of significance, in terms of tradition, history, civilization, population, and modernization” (Deng, 2012, 12). The Chinese leadership has realized the critical importance of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for China’s modernization, and elevated informatization to “the mother of all modernizations” (Zhao, 2007, 97). The deployment of ICTs has thus become a top priority (ibid., 98). China’s modernization processes have gone through revolutionary changes. The country has learned to live with both modern capitalism and rapid cyberization in a very short period. According to Chu and Cheng (2011, 25), “there is nothing in the history of Western countries that compares to China’s experience as such.”

However, beneath the “Chinese success story,” the Chinese society has become fragmented, polarized, and deeply divided by inequality (Zhao, 2007). As social stratification, class polarization, and cultural displacement are increasing, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is trying to harmonize the residents of China “by reinventing itself as a corporatist party claiming to represent the interests of all sectors of Chinese society,“ as Zhao (2007, 102) observes, with reference to Madsen (2003, 109). However, “it has not found a coherent answer to the challenges of reconciling social interests that are fundamentally incompatible with the Marxist framework that it officially still espouses” (Zhao, 2007, 102). As Bell concludes, “Communism has lost its capacity to inspire the Chinese” (2010, xx). The author also suggests that Confucianism may become a new solution. New Confucians have argued that “only by returning to a Confucian foundation can Chinese societies maintain a solid culture” (Rainey, 2010, 183).

The purpose of the study is to investigate how Confucianism is influencing contemporary Chinese society. It presents the analyses of grass-roots-generated videos shared on Youku, the Chinese version of YouTube. Thematic narrative analysis has been applied to the investigation of about 20 hours of videos. Quantitative and qualitative results aim at answering the following two questions: (1) Are patterns of the Confucian values thematically represented in the user-generated videos in the People’s Republic of China? (2) What is the role of Confucianism in the ongoing formation of an online socio-culture?

About 2,500 years ago, Confucius (孔 夫 子 kongfuzi, 551–479 BCE) transformed the more ancient cultures in China by laying the foundations of Confucianism (儒 家 rujia) (Yao, 2000, 17). During the following two millennia, the Chinese scholars and literati sought to adapt Confucianism to the new situations and circumstances of the changing times. In the course of its history, Confucianism has experienced three major “waves” of changes: the one of the era of Confucius himself, the one of Neo-Confucianism and the one of New Confucianism (cf. Littlejohn, 2010).

Angle describes Confucianism as “an ethical teaching advocating benevolence and filial devotion,” whose classical texts “are filled with aphorisms, stories, and dialogues.” The essence of Confucianism, according to the author, is “the ideal of all individuals developing their capacities for virtue – ultimately aiming at sagehood – through their relationships with one another and with their environment” (Angle, 2012, 1-2).

The modern history of China suggests that there has been discontinuity in Confucianism. In 1905, the reform of the Qing Empire led to the abandonment of the civil-service exam system with its emphasis on Confucian classics. The end of this tradition marked “a major challenge to the significance of Confucian learning” (Angle, 2012, 3). The May Fourth Movement in 1919 and later the New Culture Movement blamed Confucianism as the cause for the intellectual, political, and social failures in China. This culminated in the defeat of the Chinese Confucian state and its surrender to Western powers. “Under the direction of Mao and the [so-called] Gang of Four, the anti-Confucius campaign reached its climax during the disastrous Cultural Revolution (1967–1977)” comments Liu (2012, 93).

Nonetheless, the link between Sun Yat-sen’s “Three Principles of the People” (三 民 主 义sanmin zhuyi) and the Confucian “Grand Unity Society” (大 同 社 会 datong shehui) is “so strong that very few people would deny that the former is to some extent a succession of the latter” (Hang, 2011, 438). The Communists at the time were in fact deeply inspired by the Confucian moral code as well. As many scholars have observed, there are implicit and explicit echoes of Confucianism in the widely-read book How to Be a Good Communist, whose author, Liu Shaoqi (1898–1968), was second in leadership order after Mao Zedong (Lagerkvist, 2010, 130). However, it was only after Mao’s death that China returned to a more moderate policy, and only in recent years has the assessment of Confucius and Confucianism begun to change. Since the beginning of the third millennium, Confucianism has been considered “like a phoenix reborn from the ashes” (Liu, 2012, 93) in China.

Many reasons for a more favorable climate for New Confucianism have been discovered since the late 1980s. According to Makeham, “the single most immediate factor was the Chinese government’s support for research on New Confucianism. In November 1986, ‘New Confucianism’ was identified and funded as a key research project under the national seventh five-year plan for the social sciences” (2003, 33-34).

In 2004, the International Chinese Language Council (国 家 汉 办 guojia hanban) was established. By the end of 2010, according to the Confucian Institute (2013), “322 Confucius Institutes and 369 Confucius Classrooms were established in 96 countries. In addition, some 250 institutions from over 50 countries have expressed requirements for establishing Confucius Institutes/Classrooms.” Their goals are to spread Confucius’s teachings, the knowledge of Chinese culture. In addition, public schools in China have begun to develop a new syllabus that includes Confucian texts such as the Analects (Billioud, 2007).

In 2006, China Central Television (CCTV) broadcast the “Insights into the Analects” by Yu Dan for seven days as part of its Lecture Program (百 家 讲 坛 baijia jiangtan). Yu Dan, professor of media studies at China’s Beijing Normal University, aims at helping people deal with the pressures of modern society with advices, which has been summarized by Bell as follows: “So long as our hearts are in the right place, things will be OK” (2010, xxix). It indicates that people should not worry too much about material goods, but should develop inner attitudes. Yu Dan’s messages were overwhelmingly popular, and her book, Yu Dan’s Notes on the Analects, has “sold more copies than any book since Mao’s Little Red Book (actually, most of Mao’s books were distributed for free)” (ibid.). There are many other prominent Confucian intellectuals in China, of whom many are listed on the website of the International Confucian Network.

The aforementioned political and academic developments are supported by economic factors. Confucianism has even been made responsible for the economic miracle in all East Asian countries. “The Weberian view that Confucianism is not conducive to economic development has come to be widely questioned in view of the economic success of East Asian countries with a Confucian heritage,” says Bell (2010, xi). New Confucians develop a new confidence in the Confucian tradition. Tu has argued that the Confucian values and ethics remain “inherent in Chinese psychology and underline East Asian people’s attitudes and behavior” (1996, 259).

It may be too early to claim that the CCP has fully embraced Confucian values because only four months after its unveiling on Tiananmen Square, a Confucius statue was removed from there in April, 2011. Nevertheless, since former Chinese presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao advocated 小 康 社 会 (moderately prosperous society) in 1997 and 和 谐 社 会(harmonious society) in 2004 respectively, the Chinese leadership has offered an official dialogue concerning the revival of Confucian values.

China is experiencing a breathtaking development of its information and communication technologies (ICTs). Since July, 2008, it has overtaken the United States as the country with the largest Internet population worldwide (Lagerkvist, 2010, 12). By June, 2013, the number of Internet users in China was over 591 million, larger than the population of all EU countries together. 14.69 million domain names and 7.81 million websites have been registered under .CN. The international connection bandwidth was 2,098,150 Mbps. The number of online video users reached more than 389 million by June, 2013, which amounts to 65.8 percent of the number of Internet users in China (CNNIC, 2013).

The phenomenal development of the Internet in China has triggered many academic debates. Herold (2011) sees four main issues:

- There is the issue of control by and resistance against the propaganda management, censorship and self-censorship, advanced blocking and filtering technologies, which have been developed not only by China but also by transnational companies, so that the Internet has become an instrument to govern and to gauge public opinion. The Internet is also offering Chinese citizens new ways of resisting the Party-state’s hegemonic rule in a confrontation of the “evil” government with “good” Internet users.

- The Internet is being considered a tool for interaction and organization, offering highways on which social organizations and movements can try out new forms of technology to reach wider audiences.

- The Internet is seen as a motor of progress and development. Its impact on China’s development and its less-developed areas is the major issue in this context.

- The Internet is a new form of (interactive) media offering not only online entertainment, ideology, consumption, but also online games, violence, and pornography to youngsters.

Authoritarian political discourse is creating highly critical debates on the “Chineseness” of the Internet. According to Herold, the state or state-controlled entities “own the physical backbone of the Internet in China and privately held companies can rent bandwidth only from them” (2011, 1). Thus, the central government of China has the default “position of control over and ownership of Chinese cyberspace” (ibid.). This is one of the defining features of the Internet in China (Zhao, 2012, e.g., called it “Chinanet”). The development of ICTs is seen as instrumental in the state’s modernization of “its military and surveillance capabilities” (Zhao, 2007, 92). If so, the paradoxical nature of China’s digital revolution becomes more easily understandable. On the one hand, ICTs have been widely promoted; on the other, control over contents of, and access to, ICTs has always been a focus of the Chinese government (cf. ibid.). The strategies used by the government to control the Internet include the Great Firewall, ISP-enforced blacklisting of specific words or phrases, the coercion of multi-national technology corporations and real-world access controls (Herold, 2011, 2).

Towards the end of the 1990s, the Internet in China was in fact less controlled than it is today. Private web portals, such as Sina and Sohu, were then able to write political news stories on their own accord. However, since 2001, private portals have been banned from publishing news. They are now obliged to copy political news items only from approved media organizations, like XinhuaNews Agency and the People’s Daily (Lagerkvist, 2010, 99). Under these circumstances, “breaking social taboos has become a profit-making strategy for the Chinese-run Nasdaq-listed web portals in China” (Lagerkvist, 2008, 197).

According to Søraker (2008), nontextual information consisting of images, podcasts, videos, or three-dimensional models can hardly be intercepted by Internet service providers although these are mainly controlled, surveyed, and filtered by the Chinese government. That is the reason why the Chinese government obliges nontextual websites, such as Youku, to apply self-censorship.

Launched in 2006, Youku is the largest market shareholder of the online video sharing industry in China. More than 90 percent of its users are located in Mainland China (Alexa, 2013). Youku is also seeking to expand both in China and globally, for example, through a merger with Tudou (Zhao, 2012). Although the majority of its contents are produced professionally in order to attract advertisement funding, Youku supports amateur videos. For instance, they encourage users to generate and upload videos to its website. Youku addresses these users as Paike (拍 客), persons who use easily-accessible video recording devices, such as video cameras and mobile phones, to record exciting or current events and to share them on the website (Youku, 2012, 41).

From a commercial standpoint, it is essential for Youku to take into account the people’s interests because the private media sector needs to improve public relationships and cultivate the image of caring for people who vote with a click of the mouse. On the other hand, Youku needs to maintain good relationships with the Chinese government in order to stay on the market (Lagerkvist, 2010, 138). As a nontextual website, Youku has to sustain an effective self-censoringsystem to filter the videos as required by the government. This system has been described as a “video fingerprint system.” Victor Koo, Youku’s founder and CEO, considers it a system that can “map out any video that is the same as the video being uploaded in the past. If the video was approved or unproved before, it would automatically get treated. If the video was not in the proved or unproved list, we actually have a team of people who screen those materials” (Koo, 2009).

When China’s cyberization is discussed in the context of liberalization and democratization, there is a tendency to marginalize the importance of China’s history and cultural traditions. Chu and Cheng (2011, 37) criticize this tendency as follows: “As social actors, Chinese ICT users are embedded in a particular socio-political environment and cultural tradition. While the use of ICTs affects the manifested level of their lives, at a deeper level, the social actors have a role to play in the construction and changing of meanings.” The authors also quote Fei Xiao-tong who wrote in 1947 that the Chinese “organize their society by adopting a ‘differentiated mode of association’ (chaxugeju) based on Confucian ethics” (ibid., 28), which means treating individuals not on equal terms, but rather focus on the relationships between people. Another author quoted by Chu and Cheng is Francis Hsu. Hsu has coined the concept of “situation-centered nature of Chinese culture,“ which he defines as follows: “The preferred outcome of an interaction does not depend on individual desires in itself, but on who is involved and/or affected by the situation – the desire of the self in initiating an act or a decision is less important” (ibid.).

Hang (2011, 439) observes that “the combination of Confucian values and modern qualities creates a new title for business leaders in China, the ‘Confucian entrepreneurs’ (儒 商 rushang), for their demonstration of Confucian values such as humaneness, sincerity and truthfulness.” For instance, Youku, as a market player, has to handle well the relationship with both the government and the users. Even though some scholars argue that Youku has the chance of improving free information flows due to its nontextual contents that is beyond the Great Firewall’s filtering capability, this does not mean that Youku will take a laissez-faire path. Instead, Youku cares about social responsibility by advocating social civilizing activities. For instance, it encourages users to upload videos about people doing good deeds under the theme “to be a doer, not a passer-by” (不 做 看 客 做 侠 客 buzuo kanke zuo xiake).

Many arguments indicate that “public discourse and folk narratives have the power to influence the authoritative body and effect social change” (Xu, 2012, 23), for instance, by means of critical online genres, such as parody and satire (恶 搞 egao). Nonetheless, these are not really efficient in subverting the authoritative political discourse because “Gross-Mud Horse,“ “River Crab” and the like are mere complaints. Voci (2010) examines the Chinese online independent movies, such as egao movie, animation, or short political documentary, and concludes that they are only “light.” The author argues that these “light” movies resist to being framed into, and validated by, market, art, or political discourse and believes that their “lightness” does not create political dissent but only some disturbance in the dominant ideology. If one holds a chameleonic view of the CCP, one can find that it has fully embraced changes. The resilience of the dominant ideology can also be widely recognized. Under these circumstances, forming an online Confucian social-culture might be one of the options for solving moral crises and other social problems for the large number of the Internet users in contemporary China.

According to Bell (2010, 165), most people in China “do not want to be viewed as individualistic. The idea of simply focusing on individual well-being seems too self-centered. To really feel good about ourselves, we also need to be good to others.” This mentality is rooted in Confucian values whose presence on the internet will be examined in this section.

On July 31, 2013, I collected the most viewed top 300 Paike (拍 客) videos from Youku Paike website[1], altogether 19 hours, 47 minutes, and 18 seconds of material. The individual video screen-running time ranges from 11 seconds to 29 minutes 38 seconds. The view counts are between 1,755,497 and 27,968,944. The videos were uploaded between 2007 and July, 2013. In terms of the yearly numbers, there is an upward trend, as shown in Table 1.

When such a large amount of audiovisual narrative data needs to be analyzed, it is appropriate to apply thematic narrative analysis. On the one hand, thematic analysis can efficiently reduce the quantity of data to a realistic level and provide a bird-view perspective; on the other hand, my primary attention is directed towards video contents. Riessman (2008, 53) has clarified that all narrative inquiry is “concerned with content – ‘what’ is said, written or visually shown – but in thematic analysis, content is the exclusive focus.” Each video has a caption, sometimes also a brief textual description provided by the uploader. In this research, the caption, the video, and the textual description, if provided by the uploader, are perceived as one narrative entity for investigating themes. The thematic categories have been developed both inductively and deductively. Intra-coder reliability, which is also one of the limitations of this research since no second coder can be relied on, has been tested twice. The first time, it gained a rate less than 70 percent. Two weeks later, the second test was carried out, reaching the rate of 89.93 percent, which indicates that the coding is relatively stable.

Table 1: The most viewed top 300 Youku Paike videos: yearly distribution of number of videos and screen-running time of videos (2007 – July 31, 2013).

|

Uploading year |

Number of videos |

Screen-running time of videos (hh:mm:ss) |

|

2007 |

1 |

0:04:01 |

|

2008 |

9 |

0:51:48 |

|

2009 |

19 |

1:34:44 |

|

2010 |

21 |

1:21:41 |

|

2011 |

70 |

5:38:05 |

|

2012 |

100 |

5:23:48 |

|

2013 (till July 31) |

80 |

4:53:11 |

|

Total |

300 |

19:47:18 |

The main thematic narrative categories conducted in this study are: Confucian and

non-Confucian themes. The Confucian themes are filial piety, dutifulness, wisdom,

courage, sympathy and ritual:

Filial piety is central to all basic human relationships. It postulates “respect and reverence for one’s parents – [which] is then extended to one’s teachers and other elders” (Rainey, 2010, 24). It is claimed to be the basis of Chinese culture.

Dutifulness refers to fulfilling one’s obligations and duties, as set out in “one’s hierarchical role.” Its contemporary sense can be exemplified in all professions.

Wisdom: What wisdom brings to us is knowledge of ourselves and of how to deal with the people in the world around us.

Courage: Real moral behavior in the real world requires courage. “Courage by itself is no guarantee of moral behavior; courage in the service of morality generates the energy to carry out that moral behavior” (Rainey, 2010, 32). For instance, saving people’s lives.

Sympathy is to image ourselves in other persons’ situations, which takes us beyond “our personal inclinations and greed” (ibid., 33).

Ritual is a moral action that ensures a proper, civilized society. Carrying out rituals requires respect and being humane. For instance, marriage, funeral, and festival.

All Confucian moral values are interrelated, and they can be subsumed under the umbrella concept of 仁 (ren) – “benevolence,” “humaneness,” “humanity,” “goodness,” “care,” etc. The practices of Confucian values are located in human relationships. Our behavior and duties depend on what our roles are in relationships, e.g., the Confucian five basic relationships of ruler and government minister; father and son; elder brother and younger brother; husband and wife; friend and friend. Tu says that these five basic relationships can still find their meanings in today’s modern world – “The principle of reciprocity as a two-way traffic of human interaction defines all forms of human relatedness” (Tu, 2000, 263).

The non-Confucian thematic categories are divided by two subcategories: (1) negative values unrelated to Confucianism, and (2) negative values that are opposites of Confucian values. The former are composed of the third level categories[2]: talent show, human interest, entertainment, disasters, and others. The latter are also further divided by the third level themes: undutifulness, unrighteousness[3], mercilessness, and impiety.

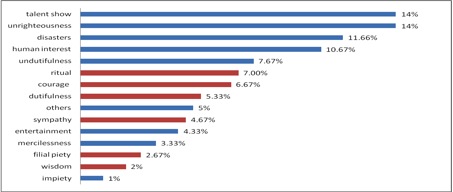

Figure 1: Percentages of video screen running time of the narrative themes, 2007-July 31, 2013 (total screen-running time: 19:47:18).

Figure 2: Percentages of video numbers of the narrative themes, 2007-July 31, 2013 (total video numbers: 300).

From Figures 1 and 2[4], it can be gathered that non-Confucian categories are predominant. Talent show, human interest, and the values that are opposites of the Confucian ones appear most frequently among the data. Themes of Confucianism are scattered and have low frequency levels.

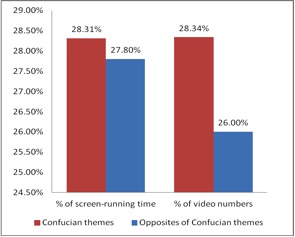

Figure 3 shows the distribution of Confucian and non-Confucian values. In terms of screen-running time, more than 28 percent of the audiovisual data tell and show narratives of Confucian values. In terms of the numbers of videos, also over 28 percent out of 300 videos represent Confucian values.

Figure 3: Percentages of Confucian themes and non-Confucian themes out of the total video screen-running time and video numbers, 2007-July 31, 2013.

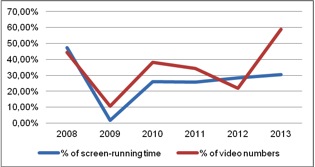

Figure 4: Yearly percentages of video screen-running time and video numbers of Confucian themes, 2008-July 31, 2013.

Figure 4 represents the yearly trend of the narratives of Confucian contents. The year 2007 is excluded since only one video was uploaded then among the top 300 videos. Generally, there is a trend of increase in the percentage of Confucian values, especially in 2013. In 2009, the quantity of the videos’ screen-running time reached the lowest point with less than two percent. This is due to the high proportion (almost 50 percent, as shown in Table 2) of videos showing people’s talents. In 2009, Youku launched the “Project Niu Ren, with the aim of promoting online talents” (Youku, 2009). For example, “Xidan Girl,” a girl who sang with a guitar in Beijing’s Xidan subway station, became a runaway success after a Paike video about her talented singing being uploaded to Youku.

Table 2: Yearly top three most frequent narrative themes (percentages out of yearly video numbers, 2008 – July 31, 2013).

|

Year

Rank |

2013 (till July 31)

|

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

2009 |

2008 |

|

Top1 |

talent show 12.50% |

unrighteous-nessn 21% |

talent show 14.29% |

talent show 19.05% |

talent show 47.37% |

human interest 22.22% |

|

Top2 |

human interest 12.50% |

disasters 12% |

ritual 11.43% |

unrighteous-ness 14.29% |

unrighteous-ness 15.79% |

ritual 22.22% |

|

Top 3 |

dutifulness 8.75% |

courage 11% |

undutifulness 10% |

human interest 14.29% |

human interest 10.53% |

filial piety 11.11% |

Among the top three categories in Table 2, which appeared most often, Confucian

themes can also be found, such as dutifulness, courage, ritual, and filial piety. The

numbers of videos relating to filial piety can be expected to increase from the

second half of 2013 on. The newly amended Law on the Protection of the Rights and

Interests of the Elderly took effect on July 1, 2013. It requires adult citizens

visiting or keeping in touch with elderly family members on a regular basis. China

Daily on July 3, 2013 reported: “According to the Ministry of Civil

Affairs, there were 185 million people aged 60 or older in China at the end of 2011,

accounting for 13.7 percent of the population. The number is expected to exceed 200

million this year.” Taking care of the elderly is a traditional Chinese virtue.

Legalizing it has triggered many debates in the society. This may be the reason for

the increasing number of Paike videos covering this theme.

Castells (2009, 194) states that media are “the space of power-making. The media constitute the space where power relationships are decided between competing political and social actors.” He adds that in nondemocratic regimes “without breaking through the organizational and technological barriers that structure information and socialized communication, the windows of hope for change are too narrow to allow effective resistance to the powers that be” (ibid.). In China, the authoritarian regime controls over both mass communication and mass self-communication[5]. The control over the mass media is hierarchically tight. It seems that mass self-communication can provide a space for the grass roots to express their complaints and critical opinions under the guise of criticizing those social values opposing to Confucian ones.

As shown in Figure 5, there are slightly longer video screen-running time and higher video numbers representing Confucian values than ones narrating the opposites of Confucianism. However, Figures 1 and 2 show that the themes representing values that are the opposites of Confucian ones, such as unrighteousness and undutifulness, are ranked among top five. For instance, fourteen percent of the 300 videos narrate unrighteousness, ranked top one in Figure 2, which mainly refers to violence and crime; 12.58 percent of the video screen-running time, ranked number two in Figure 1, portrays undutifulness, such as undutiful behaviors of 警 察 (police officers), 城 管 (city administration officers), and 教 师 (teachers).

Figure 5: Percentages of Confucian and Opposites of Confucian themes out of total video screen-running time (19:47:18) and video numbers (300), 2007-July 31, 2013.

The video, 实 拍 准 载 6 人 面 包 车 挤 下 66 个 孩 子[6] (66 children were jam-packed by kindergarten teachers in a 6-seat-bus), portrays kindergarten teachers risking 66 children’s lives by jam-tracking them into an only 6-seated bus for saving money to commute them. Their parents spend a good amount of fees to the kindergarten for caring and education. However, for a bit of benefits, kindergarten teachers would dare to put children in tremendous danger. Or, as portrayed in the video 辽 宁 东 港 惊 现 城 管 打 骑 板 车 的 老 大 爷[7] (Donggang city administration officers beat an old man who lives depending on taxi-like three-wheel bicycle!), 城 管 (city administration officers) abused their power given by the government over those low income and low social strata people who intend to be self-employed, be they migrants or unemployed.

President Xi Jinping (2013) says 中 国 梦 归 根 到 底 是 人 民 的 梦, 必 须 紧 紧 依 靠 人 民 来 实 现, 必 须 不 断 为 人 民 造 福 (The Chinese dream is the Chinese people’s dream, which can be realized only through relying on the Chinese people and through serving people for their well-being). Ironically, this political ideal encounters practical contradictions in daily life, as portrayed in the user-generated videos.

As shown in Figure 1, 4.70 percent of the total video screen-running time has been coded as mercilessness, pointing to the inequality between the rich and the poor. Chinese people’s income gap has been constantly increasing during the past years. According to the CIA “World Factbook,” China’s income Gini coefficient[8] was as high as 47.4 in 2012. “China has 2.7 million U.S. dollar millionaires and 251 billionaires, according to the Hurun Report, but thirteen percent of its people live on less than $1.25 per day according to United Nations data” (Yao and Wang, 2013). Among the 300 Paike top hits, ten videos depict rich people insulting poor people. Rich people, in the Paike videos, simply refer to those who drive luxury cars. Poor people, by contrast, refer to those who either drive poor cars, or are small-size business owners. In the Chinese language, there is a special phrase to criticize this type of rich people, 为 富 不 仁 (weifu buren, with wealth, without sympathies). The Economist on May 4, 2013 indicated worries about the Chinese dream for the potential risk that “the Chinese dream ends up handing more power to the party than to the people.” In addition, I would argue that there is another risk that the Chinese dream might hand more power over to the minority of the rich than to the majority of the poor people.

The Paike video 痴 情 男 筹 钱 救 白 血 病 女 友, 不 离 不 弃 释 真 爱[9] (Supporting his diseased girlfriend, he shows true love) lasts 7 1/2 minutes and was uploaded on May 12, 2013 on the Youku Paike website. By the end of July, less than two months after being uploaded, it had received 1,755,587 view counts, about 2,000 comments. 4,000 viewers rated to like this video. Hence, it was linked and shown on other social media sites as well, e.g., QQ Space, Sina Weibo, Renren, Tengxun Weibo, etc., over 5,000 times. It became a viral video with portrayals of ordinary people’s story in different tones from those satire videos that are full of mocking tricks.

The story in this video is about a young couple, Jiang Lusheng and his girlfriend Gong Shan,who are the so-called 80后, the generation born in the 1980s. Five months after they became boy and girl friends, Gong was found having cancer. Nonetheless, Jiang decided not to break up with Gong, to support her, instead. However, the fatal disease required a very expensive surgery, which costs ¥500,000 RMB. This amount of medical treatment fee was too high for them to afford since they were ordinary people without any efficient health insurance. In fact, in 1992, the Chinese government has begun to reform the health care system and to gear it to market requirements. However, the reform made Chinese people’s medical care fees more and more expensive. For example, between 2005 and 2012, medical expenditures have increased 19 percent yearly, from ¥662 RMB in 2005 to ¥2163 RMB in 2012 per person, which is much higher than the speed of GDP’s growth (Lang, 2013).

To raise this large sum of money, Jiang had to start a small business on the roadside market in the evening. However, it was far from being enough. Being helpless, Jiang then sent messages on social media to ask for help. Many people, after receiving this message, were touched by Jiang’s true love and sympathized with the young woman. They donated money to support Gong’s medical treatment. On March 6, 2013, Gong received the surgery, which was a success.

The two are only an ordinary couple, like any other couples we meet in everyday life. Their life-and-death crisis story might not be sensational or worthy for some mainstream media to cover. Had there not been the online space for the young man to ask for help, a tragedy could have happened. Social media provide such a space for ordinary people who struggle for life and care for others. Combining moving images, sound bites, background music, and texts, the Paike video portrays this story vividly. Nevertheless, in this narration of a hard fate brought about by a corrupt health care system, neither a critical tone nor any ridicule can be found. Instead, the messages sent by such narratives are love, sympathy, and a flourishing online community moved the ethics of caring and humaneness. The internet users’ online and offline life get intertwined, and thus they can practice social roles in the immense network as well as express identities which they might never have been able to express otherwise.

The results of this study have shown that about one third of the most viewed top 300 user-generated videos uploaded between 2007 and July 31, 2013 could be interpreted as conveying Confucian ideals. One third of theese user-generated videos contain criticisms of social stratification, power abuse, and moral decay under the guise of criticizing the behavior not in accordance with Confucian values. The study also showed a slightly increasing trend in the spread of Confucian values.

From the official discourse, as it is reflected in the current profile of Chinese grass-roots videos, it seems that the revived traditional Confucian heritage has acquired new meanings in the life of ordinary people. The Confucian values are both referred to when it comes to criticize politics (with the Internet as a potential for breaking through the control of the authoritarian regime over communication) and when the construction of an online Confucian socio-culture is at stake. This confirms the hypothesis that Confucianism can serve as a support for ordinary people facing the challenges of China’s modernization. It can also serve as a tool for social actors who advocate and propagate humanistic values in the flourishing online culture. Hence, there is hope that the Chinese civilization can be reinforced through the combination of traditional values and modern cyberization. The New-Confucian Tu Wei-ming points out, “as the first non-Western region to become modernized, the cultural implications of the rise of ‘Confucian’ East Asia are far-reaching” (2000, 263-4).

1Accessed July 31, 2013. http://www.soku.com/search_video/q_%E6%8B%8D%E5%AE%A2_orderby_3

2Talent show, in this study, refers to ordinary people showing their talents of painting, singing, dancing, etc. in the user-generated videos. The categories – human interest, entertainment, and disasters – are coded in the research project Automatische Identifikation und Klassifikation von Personen als Key-Visual-Kandidaten (Automatic Identification and Classification of Persons as Key-Visual-Candidates) between 2008 and 2012 by Professors Otthein Herzog and Peter Ludes (e.g., one of the research project presentations http://www.keyvisuals.org/research-projects-mainmenu-79/presentations-prof-dr-peter-ludes-mainmenu-81/presentation-2013.html).

3Unrighteousness is opposite to the Confucian value Righteousness that refers to knowing what is proper and what is (morally) right based on one’s duty in a situation.

4Confucian themes are highlighted in red; non-Confucian themes are marked in blue.

5“[W]ith the diffusion of the Internet, a new form of interactive communication has emerged, characterized by the capacity of sending messages from many to many, in real time or chosen time, and with the possibility of using point-to-point communication, narrowcasting or broadcasting, depending on the purpose and characteristics of the intended communication practice. I call this historically new form of communication mass self-communication. It is mass communication because it can potentially reach a global audience, as in the posting of a video on YouTube, a blog with RSS links to a number of web sources, or a message to a massive e-mail list. At the same time, it is self-communication because the production of the message is self generated, the definition of the potential receiver(s) is self-directed, and the retrieval of specific messages or content from the World Wide Web and electronic communication networks is self-selected” (Castells 2009, 55).

6Taken from http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMzA0Mzg1ODk2.html on July 31, 2013, Berlin Time. Video screen running time: 03:18 (mm:ss); key audiovisual narratives are from 00:00 to 00:15.

7Taken from http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNDMzMjk3NTI4.html on July 31, 2013, Berlin Time. Video screen running time: 06:19 (mm:ss); key audiovisual narratives are from 02:30 to 02:45.

8“Income Gini coefficient: Measure of the deviation of the distribution of income (or consumption) among individuals or households within a country from a perfectly equal distribution. A value of 0 represents absolute equality, a value of 100 absolute inequality” (UNDP 2013, 155).

9Taken from http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNTU1NjU3NTY0.html on July 31, 2013, Berlin Time. Video screen running time: 07:32 (mm:ss); key audiovisual narratives are from 05:55 to 06:10.

Alexa. 2013. Site Info: Youku. Accessed September 8, 2013. http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/youku.com

Angle, Stephen C. 2012. Contemporary Confucian Political Philosophy: Toward Progressive Confucianism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bell, Daniel A. 2010. China’s New Confucianism: Politics and Everyday Life in a Changing Society (New in Paper). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Billioud, Sebastien. 2007. Confucianism, Cultural Tradition, and Official Discourse in China at the Start of the New Century. China Perspectives 2007(3): 50-65.

Castells, Manuel. 2009. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook. Field Listing: Distribution of Family Income – Gini Index. Accessed November 26, 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2172.html .

China Daily. July 3, 2013. The Duty of Visiting Elderly. Accessed August 12, 2013. http://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2013-07/03/content_16712557.htm .

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). 2013. 中 国 互 联 网 络 发 展 状 况 统 计 报 告 (2013年 7 月) [Statistical Report on Internet Development in China (July 2013)]. Accessed August 20, 2013. http://www.cnnic.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201307/P020130717505343100851.pdf .

Chu, Rodney W. and Chung-tai Cheng. 2011. Cultural Convulsions: Examining the Chineseness of Cyber China. In Online Society in China: Creating, Celebrating, and Instrumentalising the Online Carnival, edited by David K. Herold and Peter Marolt, 23-39. London: Routledge.

Confucian Institute. 2013. Classroom. Accessed August 12, 2013. http://english.hanban.org/node_10971.htm .

Deng, Zhenglai. 2012. Academic Inquiries into the Chinese Success Story – Introduction. In Globalization and Localization: The Chinese Perspective, edited by Zhenglai Deng, 1-18. Singapore: World Scientific.

Hang, Lin. 2011. Traditional Confucianism and Its Contemporary Relevance. Asian Philosophy: An International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East 21(4): 437-445.

Herold, David K. 2011. Introduction: Noise, Spectacle, Politics: Carnival in Chinese Cyberspace. In Online Society in China: Creating, Celebrating, and Instrumentalising the Online Carnival, edited by David K. Herold and Peter Marolt, 1-19. London: Routledge.

Koo, Victor. 2009. Is China Now Changing the World Wide Web? Asia Talk. DW-TV video, 26:19. December 15. Accessed August 22, 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-3dm1TPzKU .

Lagerkvist, John. 2008. China’s Online News Industry: Control Giving Way to Confucian Virtue. In China’s Science and Technology Sector and the Forces of Globalisation, edited byElspeth Thomson and Jon Sigurdson, 191-205. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

Lagerkvist, John. 2010. After the Internet, before Democracy: Competing Norms in Chinese Media and Society. Bern: Peter Lang.

Lang, Xianping. 2013. 看 病 怎 么 这 么 难? (Why is It so Difficult to get Medical Treatment?) Guangdong Satellite TV video, 39:50. August 18. http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNTk3Nzk1OTc2.html . Accessed August 23, 2013.

Littlejohn, Ronnie L. 2010. Confucianism: An Introduction. London: Tauris.

Liu, Shuxian. 2012. Contemporary New Confucianism: Background, Varieties, and Significance. In Contemporary Chinese Political Thought, edited by Fred Dallmayr and Tingyang Zhao, 91-109. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Madsen, Richard. 2003. One Country, Three Systems: State-Society Relations in Post-Jiang China. In China after Jiang, edited by Gang Lin and Xiaobo Hu, 91-114. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, and Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Makeham, John. 2003. The Retrospective Creation of New Confucianism. In New Confucianism: A Critical Examination, edited by John Makeham, 23-53. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Metzger, Thomas A. 2005. A Cloud across the Pacific: Essays on the Clash between Chinese and Western Political Theories Today. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Rainey, Lee Dian. 2010. Confucius and Confucianism: The Essentials. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. Accessed July 20, 2013. http://jacob.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=534004 .

Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Los Angeles: Sage.

Søraker, Johnny H. 2008. Global Freedom of Expression within Nontextual Frameworks. The Information Society (24): 40-46.

The Economist. May 4, 2013. China’s Future: Xi Jinping and the Chinese Dream. Accessed August 3, 2013. http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21577070-vision-chinas-new-president-should-serve-his-people-not-nationalist-state-xi-jinping .

Tu, Wei-ming. 1996. Confucian Traditions in East Asian Modernity: Moral Education and Economic Culture in Japan and the Four Mini-Dragons. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tu, Wei-ming. 2000. Multiple Modernities: A Preliminary Inquiry into the Implication of East Asian Modernity. In Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress, edited by Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel P. Huntington, 256-266. New York: Basic Books.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2013. Human Development Report. The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. Accessed November 26, 2013. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/2013GlobalHDR/English/HDR2013%20Report%20English.pdf .

Voci, Paola. 2010. China on Video: Smaller-Screen Realities. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. Accessed July 26, 2013. http://jacob.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=534243 .

Xi, Jinping. 2013. 习 近 平 在 十 二 届 全 国 人 大 一 次 会 议 闭 幕 会 上 发 表 重 要 讲 话 (Xi Jinping made a Closing Speech in the 1st Session of the 12th National People’s Congress). Xinhua News, March 17. Accessed June 24, 2013. http://news.xinhuanet.com/2013lh/2013-03/17/c_115052635.htm .

Xu, Yingchun. 2012. Understanding Netizen Discourse in China: Formation, Genres, and Values. China Media Research 8 (1): 15-24.

Yao, Kevin and Aileen Wang. 2013. China Lets Gini out of the Bottle: Wide Wealth Gap. Reuters, January 18. Accessed August 30, 2013. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/18/us-china-economy-income-gap-idUSBRE90H06L20130118 .

Yao, Xinzhong. 2000. An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Youku. 2009. Milestones. http://c.youku.com/abouteg/youkumilestones#2009 . Accessed August 31, 2013.

Youku. 2012. Annual Report. http://ir.youku.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=241246&p=irol-reportsannual . Accessed August 17, 2013.

Youku. 2013. Paike videos. Accessed July 31, 2013. http://www.soku.com/search_video/q_%E6%8B%8D%E5%AE%A2_orderby_3 .

Zhao, Jing. 2012. Behind the Great Firewall of China. http://www.ted.com/speakers/michael_anti.html . Accessed July 20, 2013.

Zhao, Ming. 2012. Global Online Video Sharing Industry. Accessed August 22, 2013. http://www.chinavestor.com/us-stock-news/73874-global-online-video-sharing-industry.html .

Zhao, Yuezhi. 2007. After Mobile Phones, What? Re-Embedding the Social in China’s Digital Revolution. International Journal of Communication 1(1): 92–120.

实 拍 准 载 6 人 面 包 车 挤 下 66 个 孩 子 (66 Children were Jam-Packed by Kindergarten Teachers in a 6-Seat-Bus). Youku Paike video, 3:18. September 15, 2011. Accessed July 31, 2013. http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMzA0Mzg1ODk2.html .

痴 情 男 筹 钱 救 白 血 病 女 友, 不 离 不 弃 释 真 爱 (Supporting his Diseased Girlfriend, He shows True Love). Youku Paike video, 7:32. May 12, 2013. http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNTU1NjU3NTY0.html . Accessed July 31, 2013.

辽 宁 东 港 惊 现 城 管 打 骑 板 车 的 老 大 爷 (Donggang City Administration Officers beat an Old Man Who lives Depending on Taxi-Like Three-Wheel Bicycle). Youku Paike video, 6:19. July 29, 2012. Accessed July 31, 2013. http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNDMzMjk3NTI4.html

Jianxiu Hao

Is a PhD Student in Intercultural Humanities, School of

Humanities and Social Sciences, Jacobs University Bremen, Germany. Her PhD research

is “Audiovisual Narratives of Crises on Youku in China and YouTube in

Germany.” She gained her Bachelor Degree in Journalism at Hebei University,

China; and she achieved a Master Degree in Global Visual Communication at Jacobs

University Bremen, Germany. Her major research interests include: audiovisual

narratives, social media, crises, modernity, and comparative research.