Introduction

In this article I propose to look at a Facebook user by going back to two

definitions in the French language: the flâneur and the badaud.

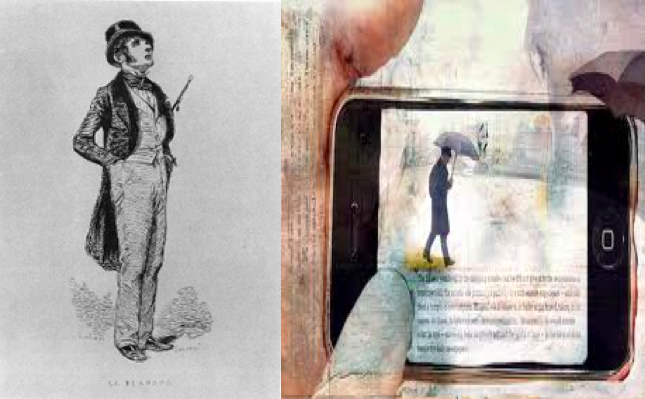

The original definition of ‘le flâneur’ is that of a stroller, a

lounger. It comes from a literary type from the 19th century Paris. The flâneur

was a man of leisure, the explorer of a city, the one who would observe the life

around him, without necessary taking an active role in it, while still being a part

of it. Walter Benjamin (1999) described the flâneur as the essential figure of

urban, modern experience. The flâneur was the investigator of modern life.

According to Benjamin the flâneur met his demise with the triumph of consumer

capitalism. The flâneur became the badaud, where individuality disappears and

where the flâneur becomes part of the crowd, losing his creativity and desire

for exploration. The badaud was also transformed by the Parisian press into an

empathic badaud, a part of the public which cares. In this paper I trace back the

development of empathic badaud and analyse how this term can be applied to a Facebook

user, which then becomes an empathetic worker. I start by looking at how the

Facebook user is looked at in academia at the current moment, then discuss in more

details the critical studies of media and information approach and explain how by

applying critical media/cultural studies we can also incorporate the dimension of

popular culture into the analysis of online social networks, and finally define a

term of an empathetic worker by discussing the experiences of the flâneur and

the badaud on Facebook and explaining the difference with the term of ‘affective

labour’.

Facebook and Critical Theory

Everyday millions of people log into Facebook to conduct sometimes important and

sometimes trivial activities. As of September 2012 the network had more than 835,525

users and the number continues to grow (Internet World Stats 2012).

Due to the rapid growth of Facebook and its high popularity, it has become an

important topic in academic research. The studies of Facebook can be classed in two

distinctive camps: on the one hand, there is research which focusses almost entirely

on the user of the network, without taking account of the macro-context, and on the

other hand, we have critical media and communication studies, as for example found in

Christian Fuchs’ work (2009, 2011, 2012, 2013), which look at the phenomenon of

online social networks within the context of capitalism.

The studies which look at online social networks without the analysis of

socio-political and economic contexts, in which these networks are based, can be

called uncritical. Most of them celebrate the potential of these networks and the

Internet in general, and point to the participatory and democratic qualities of the

medium. Thus, Henry Jenkins, for instance, argues that “the web has become a

site of consumer participation” (Jenkins 2006,137) and that blogging and taking

part in different Internet forums expand our perspectives, give us chance to be heard

and express our opinions and boost our creative potential. Alex Bruns (2007) talks

about the rise of produsage which is the “hybrid user/producer role which

inextricably interweaves both forms of participation, and that produsage

reinforces our collective intelligence, allows everyone to participate in networked

culture and can reconfigure democracy as we know it” (Bruns 2007, 27). Clay

Shirky (2008) argues that such sites as Flickr, YouTube, MySpace and Facebook create

opportunities for public participation, Don Tapscott and Anthony Williams (2006) say

that the proliferation of the Internet leads to a new economic democracy, in which

everyone has a role and can have their say, while David Gauntlett elaborated on the

capacity of social media for ‘doing culture’ (Gauntlett 2011, 11).

On the other hand, we can also see the re-emergence of critical studies of media

and communication which analyse the phenomenon of the Internet within capitalism and

point to the commodification of the medium, surveillance and the fact that the usage

of the Internet and online social networks is often dictated by big corporations,

whose main drive is profit. These studies are radically different from

‘critical’ cyberculture studies, led by such scholars as David Bell (2001),

David Silver (2006), and focus on “issues relating to class, exploitation, and

capitalism” (Fuchs 2011, 9). For Christian Fuchs, ‘critical’

cyberculture studies lack the profound analysis of the society in which the Internet

is based, and “therefore an approach that in its postmodern vein is unsuited for

explaining the role of the Internet and communications in the current times of

capitalistic crisis. The crisis itself evidences the central roles of the capitalist

economy in contemporary society and that the critical analysis of capitalism and

socio-economic class should therefore be the central issue for Critical Internet

Studies” (Fuchs 2011, 10).

The current research on online social networks is heavily dominated by these two

trends (either celebrating participatory culture or pointing to domination and

exploitation in capitalistic societies in which these mediums are used) and is either

uncritical and focusses mostly on the user or analyses mostly the macro-context in

which the medium is used.

In order to explain such a phenomenon as Facebook the integration of both

political economy and cultural studies is needed. Facebook can be seen as a miniature

society taking place online. On the one hand, it reflects capitalism through Facebook

being a corporation pursuing profit, but on the other hand, people log in there to do

their own things, they communicate with friends, upload pictures, create groups and

do many other activities which are significant for them and also for many others.

Facebook is not only a corporation but also a cultural form, and therefore, on needs

a new approach, which Douglas Kellner calls (2009) ‘critical media/cultural

studies’ and which looks at Facebook as both embedded in capitalism, but also a

tool that is enjoyed by millions of people on a daily basis and can tell us a lot

about such things as friendship, changing notions of privacy, identity and the

reflection of the celebrity culture. Critical media/cultural studies can be defined

as an approach that “reads, interprets, and critiques its artefacts in the

context of the social relations of production, distribution, consumption, and use of

which they emerge. The dialectic of text and context requires a critical social

theory that articulates the interconnections and intersections between the economic,

political, social and cultural dimensions of media culture, thus requiring multiple

or trans-disciplinary optics” (Kellner 2009, 20). This approach takes into

account the socio-political context in which the medium is based, but also reflects

upon the cultural aspects of the phenomenon and how it is manifested in the daily

lives of its users. Based on this approach, I propose to call a Facebook user an

empathetic worker.

The Facebook User as a Prosumer and Part of Affective Labour

Critical studies of media and communication (Fuchs 2011, 2012, 2013) see the user

as being exploited by the Internet and online social networks, where the data on the

users is collected, processed, analysed and then sold to advertisers. At this moment

this is the most advanced research which sees online social networks as a reflection

of informational capitalism, where we are offered a service for free but end up being

exploited through the privacy policy of the companies offering these services. On

Facebook when we sign up we agree to a very long and ambiguous privacy policy, hardly

read by anyone, and which clearly states that all the data can be sold to

advertisers.

Alvin Toffler (1980) coined the term prosumer within information society. Axel

Burns (2007) applied this term to new media and coined the term produsers - where

users become producers of digital knowledge and technology.

As Trebor Scholz (2010) argues, we produce economic value for Facebook mainly in

three ways: 1. providing information for advertisers, 2. providing unpaid services

and volunteer work, and 3. providing numerous data for researchers and marketers.

The first one is related to the fact that our mere presence on Facebook provides

invaluable information to advertisers. Starting with our birth date and finishing

with our likes and dislikes, all this can be processed by advertisers to target their

advertisements to users. The third one is in line with the argument of Nigel Thrift

(2005) that the current age of capitalism is increasingly knowing and any information

we post, in our case Facebook, can be sold to third parties and "transformed into

profitable spreadsheets" (Scholz 2010, 245).

The second economic value, providing unpaid services and volunteer work, is

especially interesting, as Facebook basically uses the labour of its users for free.

Scholz mentions that many Facebook users provide willingly their time and energy for

Facebook use. An example is the translation application, where users translate

Facebook into different languages totally for free. Roughly ten thousand people

participated in the application which allowed Facebook to be read and used in many

languages, besides English. However, also providing our data to advertisers and third

parties, by simply being on Facebook and having 'fun', also constitutes working for

Facebook and advertisers for free. Users by commenting, uploading pictures and

‘liking’ pages on Facebook generate revenues for the network, as it then

sells their data to advertisers. It can be then argued that users produce surplus

value and “engage in the production of user-generated content” (Fuchs 2009,

30).

Users of Facebook also provide data and content for the site, making it more

appealing for use, through photos, comments, etc. One of the strategies employed by

such corporations as Facebook is to lure the users through the promise of free

service, who in turn produce content. This content, in turn, is sold to third-party

advertisers.

Maurizo Lazzarato (1996) introduced the term 'immaterial labour', which means

"labour that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity" (1996,

133). This term was popularized by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri who said that

immaterial labour is labour "that creates immaterial products, such as knowledge,

information, communication, a relationship, or an emotional response" (Hardt and

Negri 2004, 108). For them the main purpose of immaterial labour is to create

communication, social relations and cooperation. Knowledge produced in this way would

be exploited by capital. "The common [...] has become the locus of surplus value.

Exploitation is the private appropriation of part or all of the value that has been

produced as common" (Fuchs 2011, 299).

As Fuchs explains the Internet is part of the commons because all humans need to

communicate in order to exist. But, as he continues, "the actual reality of the

Internet is that large parts of it are controlled by corporations and 'immaterial'

online labour is exploited and turned into surplus value in the form of the

advertising-based Internet prosumer commodity" (Fuchs 2011, 299).

This labour which works in the Internet economy for free can also be called

'knowledge labour' since 'immaterial labour' might mean that there are two substances

of the world - matter and mind (Fuchs 2011). Corporations using the knowledge labour

lure the users by offering a ‘free’ access but where users provide content

which can be turned into profit through advertisements. “Hence the users are

exploited – they produce digital content for free in non-wage labour

relationship” (Fuchs 2011, 299).

Capitalism's imperative is to accumulate more capital. In order to achieve this,

capitalists either have to prolong the working day (then it is called absolute value

production) or to increase the productivity of labour (relative surplus value

production) (Fuchs 2011). In the case of relative surplus value production

productivity is increased so that more commodities and more surplus value are

produced in the same period as previously.

Targeted Internet advertising can be called relative surplus value production

(Fuchs 2011, 2013). The advertisements are produced by advertising company's wage

workers but also by users of the online social networks, whose content in the

profiles and transaction data are used to make advertisements. Users also produce

content for free for Facebook itself, and thus, provide unpaid labour, which Fuchs

terms also 'play-labour' (Fuchs 2011). Users use such sites as entertainment mainly

and usually in their free time. But without realizing it, in their free time they

actually continue working for free for numerous Internet sites, by posting comments,

updating profiles and by buying and selling things.

Facebook is a typical example of a new service-for free model which saw a rise

under informational capitalism. In this way it is part of a new trend where our

internet activities are turned into profit by capitalists. The Facebook user is also

part of ‘affective labour’, a term used to reveal labouring practices which

“produce collective subjectivities, produce sociality, and ultimately produce

society itself” (Hardt 1999, 89). This type of labour is part of immaterial

labour discussed above, but has the goal of creating affects and is usually found in

health services, the entertainment industry and “the various culture

industries” which are “focussed on the creation and manipulation of

affects” (Hardt 1999, 95). This labour is “embedded in the moments of human

interaction and communication” and its products “are intangible: a feeling

of ease, well-being, satisfaction, excitement, passion, even a sense of connectedness

or community (Hardt 1999, 96). It is built on human contact where there is “the

creation and manipulation of affects” (Hardt 1999, 96).

However, the definition that Hardt and Negri propose deals mostly with aspects of

work seen as labour. The authors emphasise that affective labour can happen during

leisure time, which they see as exploitation mostly. In the age of informational

capitalism where work shifted even more into production of knowledge, which involves

constant creation of ideas, and often outside working time, according to Hardt and

Negri, as a result, people end up working all the time. “When production is

aimed at solving a problem, however, or creating an idea or a relationship, work time

tends to expand to the entire time of life” (Hardt and Negri 2004, 111).

However, my argument is that we should look differently at a Facebook user. Online

social networks are a reflection of informational capitalism, where the activities of

users are turned into profit, but can we call it labour time, when people logging

into Facebook or any other online social network, clearly have fun on it and do not

necessary see it as exploitation?

The Facebook User as an Empathetic Worker

I propose to call the Facebook user an empathetic worker, a definition

which takes into account both the fact that the user’s activities and feelings

are turned into profit by Facebook, but which is not necessary judged by the user as

direct exploitation. In their daily lives when people log into Facebook they think of

seeing what their friends are doing, comment on status updates, upload pictures and

experience all kinds of feelings and emotions that we do when we communicate with

friends, relatives or colleagues. I wanted to catch this aspect of interaction on

Facebook by defining a Facebook user and situating it within the critical

media/culture studies perspective which takes into account both the popular culture

aspect and also an economic and political environment. There is invisible

exploitation going on while users use Facebook, since the network uses the data of

the users for the commercial purposes, but at the same time users have fun on the

network and derive numerous benefits from being on the network. There is an interplay

going on inside Facebook. Advertisers and Facebook try to catch the trend of

interaction and consumption in order to exploit it, while ordinary people who use

Facebook simply log in there to do their own thing, sometimes trivial, but sometimes

very significant. Culture can never be contained fully, as the example of Facebook

demonstrates. We are exploited on it, but we also create there, build relations and

play with our identity. Looking at a Facebook user from the critical media/cultural

perspective, one shouldn’t give one and precise definition to a Facebook user.

The Facebook user is exploited, but also has fun and might be doing something on the

network which clearly benefits his or others’ life. And therefore, I propose to

look at the experience of Facebook’s users through 3 terms: the flâneur,

the badaud and empathetic worker.

The term of empathetic worker catches the exploitative aspect of the network, but

doesn’t exclude the possibility of looking at time spent on Facebook as leisure

time in its original sense.

Marx and Engels (1845/46) distinguished between work and labour. Work is a

necessary productive activity which serves to provide the means of subsistence.

Humans need to work in order to create food for their survival, for self-fulfilment

and as a community building. Labour, on the other hand “is a necessary alienated

form of work, in which humans do not control and own means and results of

production” (Marx and Engels 1845/46, 4). Work is more general definition. Work

is necessary in order to create goods and services. However, under capitalism work is

organised in such a way that products of labour belong to the dominant class and

therefore, work becomes an alienated labour.

Christian Fuchs and Sebastian Sevignani (2013) look at how work and labour

function on Facebook. Through work we create consciousness and language. The

activities then on Web 2.0/Web 3.0. which are the activities involving cognition,

communication and co-operation are forms of work (Fuchs and Sevignani 2013).

Cognition is related to work of the human brain, while communication involves

interaction between human groups and co-operation (Fuchs and Sevignani 2013). On

Facebook users produce value for themselves which is creative work and value for

Facebook, which becomes digital labour. “Facebook’s objects of

labour are human experiences” (Fuchs and Sevignani 2013, 259). Users while

spending their time on Facebook often share intimate moments of their lives with

their friends, upload and comment on pictures, chat, have fun or experience moments

of sadness and loneliness while they are on there. Facebook captures emotional

aspects of its users’ lives and uses it for profit. Therefore, I call a Facebook

user an empathetic worker. An empathetic worker is a user of Facebook who uses

Facebook for personal or professional reasons (mostly personal), shares intimate

moments of his life on the site, experiences feelings and emotions while

communicating with friends and relatives, and where Facebook as a corporation catches

this interaction in order to make profit. The user of Facebook is creative when he is

on Facebook, because he automatically provides some content for the corporation. But

this creativity is channelled into generating revenues for Facebook. I use the term

‘work’ instead of labour because when users of Facebook log in they do not

consider it as work, but think of Facebook as an important part of their lives and

where they mostly communicate with friends. Work on Facebook reflects work as a

necessary part of being human if we go back to the definition of Marx and Engels,

because communication, community-building and friendship are the essential elements

of the social aspect of our lives. The user is also empathetic because s/he usually

experiences and shares feelings and emotions on the network.

Empathy has a broad definition but usually involves recognising emotions of

others, caring for and recognising what other people are feeling, as well as blurring

the line between self and other (Hodges and Klein 2001). Affective labour usually

involves the aim of achieving something. The oxford dictionary defines affect as

having an effect on something and as ‘touching feelings of’, moving

emotionally.[1] This presupposes some

goal, the result of one’s actions. Workers involved in affective work, such as

in entertainment or services industry, usually try to put their customers at ease,

please them, bring them joy so that customers then either buy something or leave a

tip. Empathy, however, is a broader and more internal definition. Empathy

doesn’t need to have any aim, it can remain as an emotion experienced by one

person without the aim of moving emotionally someone else. One of the most

influential study of empathy by the philosopher Theodor Lipps (1979) looked at

empathy as a very complex notion, which included both external manifestation of our

feelings, when we respond to anger or joy experienced by another, as well as

internal, which could remain invisible inside an individual and would become the

phenomenon of ‘internal imitation’ (Lipps 1979, Stueber 2013). Empathy can

be both external and internal mirror of our emotions and feelings and empathy is more

appropriate in the analysis of Facebook, as users do not necessary always react or

want to achieve something through their comments and statuses updates. The whole

emotional aspect when users simply read something without reacting in any visible

form (such as commenting), while feeling some emotions internally, is also empathy.

The Facebook user can stare at the screen of the computer without doing anything and

still remain an empathetic worker, since he spent time on creating the account,

filling in the profile and building a network of friends. The user doesn’t need

to do anything, apart from experiencing an emotion. Empathy also involves “an

observer’s reacting emotionally because he perceives that another is

experiencing or is about to experience an emotion” (Stotland 1969, 272).

All this can be drawn back to the identity stages of George Herbert Mead (1967),

and which can be seen in how users of Facebook interact on the site. George Herbert

Mead said that the self is established through communication. The individual for Mead

was a product of society, of social interaction. For Mead, we could only see

ourselves in relation to other people. We are first an object of others, and then we

conceive the perspective of other people through language and communication we become

an object to ourselves. In the case of Facebook, we can look at our profiles as

objects of our friends, but through communication on Facebook via pictures, status

updates, profile updating, we take the perspective of others on us to communicate to

the audience. On Facebook we often project what others might think of us through

statuses updates, comments, etc.

Mead saw social interaction and identity through 'Me' and 'I'. 'Me' related to the

social self, while 'I' is the response to 'Me'. When people update their status on

Facebook or communicate what is on their mind, they present the 'me', based on

socialization they have already experienced. The 'I' maintains the Facebook profile

by selecting 'me' to project to the world and ourselves.

For Mead social existence and communicative identity is a three-step process

through which the self is developed: language, play and game (1967).

- Language: through language or communication we take on ‘the role of the

other’ which allows us to respond to our own gestures (form an opinion about

ourselves) in terms of the symbolised attitudes of others.

- Play: through play we take on roles of other people and pretend to be the

other people in order to correspond to expectations of significant others.

- Game: through game we internalise the roles of all others and form our own

identity through ‘rules of the game’ (knowing how to behave in certain

situations).

The three activities of Mead through which the self is developed can be applied to

Facebook as well: First of all, people become aware of intentions of other

individuals through their actions and gestures (Ellis 2010). For instance, when we

upload a picture on Facebook or put a status update there, we communicate something

about us to others. These others, by looking at our update or a picture, form an

opinion about us and our intentions. By commenting on pictures or links friends

‘project’ our social identity back to us. Second, we communicate our

identity to others. By putting a certain picture on Facebook, we try to project a

certain image and in general know the response in advance. By uploading a picture

from our holidays we expect others to react to it in a certain way, by commenting for

instance, what a great holiday we had. The profile picture also shows something about

ourselves. It is the 'I' which chooses 'Me'. By putting a picture of myself with a

cat on Facebook I try to show that I like this animal and that cats play an important

role in my life. Here, we also engage in impression management. We try to build a

certain image of ourselves, but this image is built on how others perceive us in our

social reality. These are the second and third stages of identity creation at the

same time since we try to impress others and also engage in the rules of the game,

such as uploading pictures on Facebook that an increasing number of people do, and

commenting under pictures in a certain way.

And finally, the picture we upload means something to us, it means something for

our social identity. "...this picture means something to the individual who is

negotiating their personal identity among the available social identities. Identity,

as it emerges in the mind of an individual, cannot be separated from social processes

and interactions" (Ellis 2010, 39). When I upload a picture of myself with a cat, I

already know that I do like cats in real life and that they are important in my

life.

Thus, on Facebook we engage in building our identity and it allows for

self-discovery, as building a Facebook profile is in a way a reflective act. While

building the profile we ask questions about ourselves: what do I want to project? How

will others perceive me? What shall I include in the profile and what is most

important for me in terms of how others perceive me? This involves the creation and

maintenance of profiles, but also interaction of users through status updates, the

uploading of pictures, participation in groups, etc. Users of Facebook log in on

Facebook to see what their friends and relatives are doing, and experience feelings

and emotions when they see the news from their friends. If someone feels lonely and

puts this fact on the status update, we usually try to cheer this person up through a

reply. Thus, we directly show that we care, but also other people can see that we

care and this contributes to the building of our own identity. We participate on the

site empathetically, by reading status updates of our friends, by sharing

moments of our lives, by commenting on the moments of lives of others. All this,

however, is used by Facebook to create personalised advertisements. The Facebook user

who logs on Facebook to communicate works for Facebook at the same time.

At the same time, as mentioned previously, the user can also experience fun while

being on the network, without feeling that s/he is being exploited. Facebook is not

only a business corporation pursuing profit, but also a site where people log in for

a multitude of reasons. Looking at the Facebook user only from the point of view of

exploitation misses the social aspect of the network. And therefore, it would be

insufficient to call a Facebook user by using one single term which would mostly

catch the exploitative and commercial aspect of Facebook. I propose to look at a

Facebook user by going back to two terms in the French language: the flâneur

and the badaud. By using these two terms we can also build another picture of

empathetic worker, based on making of empathic observer by the French Press in the

19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.

The Facebook User as the Flâneur and the Badaud

Gregory Shaya in his article ‘The Flâneur, the Badaud and the Making of

a Mass Public in France...’ traces the making of an ‘empathic

observer’ by the French press in 1960-1910 (2004). His description of how a

French stroller, the flâneur became a badaud, a consumer rather than observer

of life and then an empathic observer or ‘valorised badaud’, can be applied

to a Facebook user as well, which through the fact that the user also works for the

corporation, becomes an empathetic worker.

The flâneur, a term coming from the French language, means a stroller. It is

derived from the French noun ‘un flâneur’ which is based on the

French verb ‘flâner’ with the translation – to stroll. The

flâneur became an interest in literary and philosophic circles in the

19th century in France and became associated with a leisure figure of an

intellectual on a walk. It was Charles Baudelaire who gave the term its additional

meaning, where the flâneur became a ‘stroller with a purpose’, where

the purpose was mostly intellectual, in order to learn something new and interesting

about the city. Thus, Baudelaire defined the flâneur as someone who walks

around the city in order to experience it and learn something from it (Baudelaire

1964).

The term was popularised by Walter Benjamin (2002) who made out of

flâneur a subject of academic interest. The flâneur was a literary type

in France, a man of leisure, who would walk across the streets of Paris and observe

life around him. The flâneur was an explorer of life, a detective of the city.

He was in the crowd but also outside of it, refusing to take an active part in any

consumption, and instead walking around solely for ‘the gastronomy of the

eye’ as Balzac described the experience of the flânerie (Shaya 2004, 47).

However, with the rise of the consumption which happened after the reconstruction of

the Parisian boulevard under Baron Haussmann, giving way for more shops and creating

a “visual pleasure for an eager public” the flâneur has become a

badaud, where he mixes with the crowd and his individuality disappears (Shaya 2004,

43). As Walter Benjamin argued, the flâneur became someone who is turned into

profit. He became the badaud, the gawker – someone who stares at the objects

without reflection and takes part in the society of consumption without wondering

about its substance. The online free dictionary defines the term as “a person

given to idle observation of everything, with wonder or

astonishment”.[2] It is a person

who wants gossip and sensations.

This was also the time of the rise of the commercial mass press, which Jürgen

Habermas (1991) blamed for the decline of the public sphere, when a

“culture-debating public” transformed into a “culture consuming

public”, and where the flâneur gave way to badaud, a spectator of

‘fait divers’. The badaud, however, having often a negative connotation in

scholarly articles is not always a simple passive spectator, as can be seen in the

description of modern life provided by Guy Debord (1967). While the badaud is

certainly in search of the sensational, he is also taking part in the surroundings,

and this was exploited by the mass press in 1860-1910 in France to make out of badaud

an “empathic observer”, a part of the public that was defined by

“sensations, passions , and curiosity” (Shaya 2004, 42).

As Shaya traces this development, it was a deliberate construction of a new type

of observer and reader, to attract more curiosity to sensational facts but also

“as a mechanism of solidarity of an era of social conflict and fractured

identities” (Shaya 2004, 44) Describing a crime or an accident with pictures of

people who happened to be in the proximity, was a way to assemble the community

around a cause and boost participation in public life. Witnesses on the pictures

emerged as not simply badauds, gasping with an open mouth at the scene, but as

sympathetic and emotional observers who cared. This, of course, led later to the fact

that the press’ capturing of the popularity of ‘fait divers’ has

become even more sensationalistic, creating more of what Debord (1967) called a

society of the spectacle..

Given this interplay between the flâneur, the badaud and ‘empathic

observer’, the concept of a valorised badaud can be applied to Facebook as well.

Facebook is often used as distraction, as an alternative to boredom. Many people keep

the Facebook page open to occasionally 'check the noise', or gossip provided

willingly by their friends on the network. The fact that gossip is provided

intentionally is worth being looked upon. Facebook as never before provides a perfect

stage for dramatic performance for its participants, and relates perfectly well to

the observation of Erving Goffman that "the world, in truth, is a wedding" (Goffman

1959, 45).

On Facebook people mainly 'front', they intentionally try to create a certain

impression through their pictures, status updates, comments, etc. Facebook provides a

perfect stage for instant validation, where members have immediate access to an

audience for their performance.

It is not unusual for participants on Facebook to exaggerate their lives, make it

more sensational and more interesting. Many put only their best pictures on Facebook,

post status updates about beach holidays, parties and other events that could make

one's life more appealing. Vejby and Wittkower looked at this phenomenon in the book

‘Facebook and Philosophy’ and argue that the mass media leads to the

passive outlook at life. “Just as, in the society of the spectacle, we have

little choice but to adopt received market-integrated representations of life (buying

things), liberty (the freedom to buy whatever we want) and the pursuit of happiness

(buying more expensive things), so too does the mass media present us with a series

of images which we can only passively accept or reject – but not change, or

reply to” (Vejby and Wittkower 2010, 99). This is similar to the experience of

the badaud in France in the early twentieth century, when the badaud was looking

after sensational experiences, provided by the press and crime scenes. However, this

badaud, as already explained, wasn’t a simple gawker, he was also sympathetic

and caring, taking part in the surroundings in order to gain more experience.

The sensationalisation on Facebook reflects in general a culture that "privileges

the momentary, the visual and the sensational over the enduring, the written, and the

rational" (Turner 2004, 4). Facebook reflects the tendency in our society to be

obsessed with celebrity culture. It is a general fascination with the image and

simulation which perhaps makes Facebook so popular. On Facebook we are all badauds to

a certain extent, watching the intimate details of our friends’ lives and

deriving a sense of pleasure from it.

Facebook provides both social contact and relaxation and corresponds to our desire

for the sensational. Here, our own lives can become sensational and we become the

image makers of our own life. Not only do we watch the lives of our friends, which

relates to our innate desire for gossip, but we can also present our lives as we see

it fit.

According to Debord we live in a society where "life is presented as an immense

accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a

representation" (Debord 1967, 7) The spectacle for Debord "is a social relation

between people that is mediated by images" (Debord 1967, 7).

For Debord the authentic life has been replaced by representation. "Everything

that was directly lived has receded into a representation" (Debord 1967, 7). For

Debord the importance of life has been reduced into having – we are driven by

consumption and accumulation, and having has receded into merely appearing. Happiness

can be achieved through a new car, a new house or fashion, but this is not true

happiness, it is just an illusion of happiness. The current life has become the

pursuit of commodities where "people's activity becomes less and less active and more

and more contemplative" (Debord 1967, 34).

For Debord people became passive viewers of life instead of its active makers and

mass media is to blame for it. We are dominated by contemplation of useless

programmes about celebrities, where fame or pursuit of fame or having a new gadget

has become the main goal of life for many people. Genuine relationships have been

replaced by consumption of friendship where meeting with friends is accompanied by

shopping or consumption. Instead of doing sport we watch sport on the TV, where sport

itself became the commodity, with sport stars becoming celebrities and new idols.

Instead of singing for pleasure, singing has become the pursuit of fame and fortune

as demonstrated by popularity of such programs as X-Factor and American Idol. Instead

of living our lives actively and allowing for critical thought, we simply

spectate.

In this respect Facebook can be seen as another spectacle. On Facebook we

'spectate' our friends instead of meeting them in real life. We are bombarded with

advertisements linked to our profiles and posts, and here our life is becoming a mere

commodity, where even in profiles we are driven to fill them in according to

capitalist logic. Our profiles are dominated by the things we consume, watch and

buy.

But another way to look at it is to acknowledge this consumption as an art of

living everyday life and as creativity. By looking at Facebook as simply a spectacle

or as useless consumption misses the point of what popular culture is and that people

derive pleasure and meaning from things which can seem pretty trivial but are

significant for them. The Facebook user is also an empathic badaud, caring for the

lives of others and going on Facebook not only for entertainment but also in order to

create, to share and to experience feelings and emotions which are not linked to the

desire of the sensational.

As John Fiske argues: "Popular culture is made at the interface between the

cultural resources provided by capitalism and everyday life [...]. Popular

discrimination is thus quite different from the aesthetic discrimination valued so

highly by the bourgeoisie and institutionalized so effectively in the critical

industry. 'Quality' – a word beloved of the bourgeoisie because it

universalizes the class specificity of its own art forms and cultural tastes –

is irrelevant here. Aesthetic judgements are antipopular – they deny the

multiplicity of readings and the multiplicity of functions that the same text can

perform as it is moved through different allegiances within the social order [...]

Aesthetics requires the critic-priest to control the meanings and responses to the

text, and thus requires formal educational processes by which people are taught how

to appreciate 'great art' [...] Aesthetics is naked cultural hegemony, and popular

discrimination properly rejects it" (Fiske 1989, 130).

The point that Fiske makes is that people are controlled through work and continue

being controlled outside work by what the dominant order judges as useful and

'correct' so that the worker is ready to go back to work the next day and not

question the existing order. Fiske gives the example of pleasure and how the

capitalist system tries to control pleasure by providing its own meanings which are

supposed to be followed. Facebook is often talked down as a waste of time and as

useless consumption because many people tend to use it either at work or instead of

doing something more ‘useful’. Facebook is often relegated to something

which is dangerous and addictive, exactly because it is also a means of control over

patterns of consumption and tastes. However, the fact that Facebook is also a perfect

product of the capitalist system does not prevent some users from using it against

capitalism. There are many instances where users create protests and rallies on

Facebook itself, and actually have 'fun' with the fact that it is impossible to

control everything which happens on the network. On the other hand, would Facebook as

corporation allow any serious rally against the existing order on its network?

Something which would be seen as a real danger to the status quo? Probably not.

But while Facebook as a corporation would be unlikely to allow anything which

could create problems for its status-quo, is there also a way on the network for the

flânerie, a French word derived from the flâneur and which is associated

with the activities of the flâneur, such as discovery, intellectual curiosity,

looking at something without the aim of buying?

The term the flâneur has been a subject of renewed academic interest in the

mid-1990s with several academics creating new, derived terms from the word. We had

the ‘cyberflâneur’ (Goldate 1997), ‘Virtual flâneur’

(Featherstone 1998), ‘online flâneur’, and even postmodern

flâneur’ (Hartmann 2004). All these authors who propose the new terms for

the original flâneur argued that the experience of the flânerie acquired

a new meaning on the Internet. All these new concepts offered to look at the

flânerie as a new phenomenon. If the old flâneur was investigating

without taking part in his surroundings, then on the internet the cyberflâneur

also has the possibility to create, and thus, he also takes part in what he is

observing.

The culmination of looking at the experience of the cyberflâneur

optimistically came with the publication of the article by Evgeny Morozov in New York

Times in 2012 in which he declared that the cyberflâneur is dead (Morozov

2012). To explain the death of the phenomenon Morozov goes back to Paris in the

19th century and reminds us how the flâneur was killed then, through

the reconstruction of the city to create more shops. “Such rationalization of

city life,” he writes, “drove flâneurs underground forcing some of

them into a sort of ‘internal flânerie...” (Morozov 2012).

According to the author, any sort of flânerie on the internet reached the same

level, “transcending its original playful identity, it’s no longer a place

for strolling,” as Morozov describes the Internet, “it’s a place for

getting things done” (Morozov 2012).

However, looking at the flâneur both from over-optimistic point of view, as

was done with the term in the mid-1990s or from over-pessimistic point of view as did

Morozov, misses the rich meaning of the original term. The term flâneur has

been discussed and is still discussed in the literary circles in France, and its

original meaning is much more complex than is usually attributed to it. Then Walter

Benjamin was describing how the flâneur was turned into profit by the

department stores, he also mentions that a state of ‘in-betweeness’ is

possible, when the flâneur is attracted to the newness but doesn’t

necessary buy. “The flâneur still stands on the threshold – of the

metropolis as of the middle class. Neither has him in its power yet (Benjamin 2002,

10). As Edmunt White argues in his book where he talks about the experience of the

flâneur, it was still possible to remain the flâneur even after the

reconstruction of Paris. “Even rebuilt and outfitted with all those identical

trees...benches and kiosks, more than any other city Paris is still constructed to

tempt someone out for an aimless saunter, to walk on just another hundred yards- and

then another” (White 2008, 38).

And therefore, my argument is that we should go back to the original term of the

flâneur without re-inventing the wheel. The term is rich and complex enough to

apply it in any setting or experience. As it was still possible to stay the

flâneur among endless shops, it is still also possible to be the flâneur

on the Internet and also on Facebook. We need new terms to reflect on how any

Internet experience can be turned into profit, but we don’t need new terms to

describe all human experiences on the net. What to make out of academics who

‘stroll’ Facebook out of intellectual curiosity? What to make out of idle

observers who simply want to learn something new? What to make out of all these

people who discover something new on Facebook every day, such as some new music, an

important piece of news, or a book to read?

And this is why the Facebook user is a multitude of things at the same time. When

we log in we don’t necessary think about Facebook as a corporation, we log in

because Facebook is a part of our daily lives, our friends are on there, and we want

to see what these friends are doing and share what we are doing in return. The

Facebook user is also a flâneur when he or she wants to look at what is

happening on Facebook out of curiosity and in order to enrich his or her life. The

Facebook user is also a badaud, when he or she logs in to Facebook for the desire of

gossip, and finally, the Facebook user is also an empathetic worker. While Shaya in

his article calls the badaud an ‘empathic’ badaud, I consider the term

empathetic more appropriate for the Facebook user. Both terms are almost similar, but

there is a slight nuance of difference. Empathic is a feeling experienced by an

empath mostly in order to show that one cares. Empathetic, however, incorporates an

additional dimension, when one not only experiences emotions towards others, but also

through these emotions experiences feelings towards oneself. It is recognising what

others try to tell us on Facebook, but also sharing our own feelings in return, and

building our identity as a result. These feelings and emotions are captured by

Facebook to make a profit, and therefore, the empathetic user also becomes an

empathetic worker.

Conclusion

In this paper I analysed the Facebook user by using critical media/cultural

studies. Critical media/cultural studies acknowledge both the socio-political context

in which a medium is based (capitalism), as well as the cultural dimensions of the

medium and how it affects people in their daily lives. The Facebook user is a part of

‘immaterial labour’, he is a prosumer and also play-worker and affective

worker, if we take into account the fact that Facebook as a corporation collects data

on us and sells it to advertisers while we communicate with our friends and

participate on the site ‘socially’. At the same time, the Facebook user

experiences the network on a different level in his daily life. When we log in the

network we want to have fun, we desire some gossip, we also want to see what our

friends are doing and share what is happening in our lives with them. We do not

consider that we are exploited when we spend our time on Facebook, but usually

consider that we derive numerous benefits from using Facebook. Therefore, I propose

to call the Facebook user an empathetic worker, someone who experiences emotions

while using the medium, while these emotions are then turned into a profit.

Notes

1

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/affect

2

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Badaud

References

Babe, Robert. 2009. Cultural Studies and Political Economy:

Toward a New Integration. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Baudelaire, Charles. 1964. The Painter of Modern Life.

New York: Da Capo Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2002. The Arcades Project. Cambridge,

MA: First Harvard University Press.

Bell, David. 2001. An Introduction to Cybercultures.

London and New York: Routledge.

Burns, Alex. 2007. Produsage, generation C, and their effects

on the democratic process. Media in Transition 5, 27-29 April.

Debord, Guy. 1992. Society of The Spectacle. London:

Rebel Press.

Ellis, Katie. 2010. Be Who You Want to Be: The Philosophy of

Facebook and the Construction of Identity. Screen Education 58.

Featherstone, Mike. 1998. Virtual Flâneur. Urban

Studies 35: 909-925.

Fiske, John. 1989. Understanding Popular Culture. London

and New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2009. Information and Communication

Technologies and Society. A Contribution to the Critique of the Political Economy of

the Internet. European Journal of Communication 24 (1): 69-87.

Fuchs, Christian. 2011. An Alternative View of Privacy on

Facebook. Information 2: 140-165.

Fuchs, Christian. 2011. Web 2.0, Prosumption, and

Surveillance. Surveillance & Society 8 (3): 288-309.

Fuchs, Christian. 2011. What Does it Mean to Study the Internet

Critically? Paper presented at the 7th International Critical Management Studies

Conference. University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy. 12th 2011.

Fuchs, Christian. 2012. Dallas Smythe Today – The

Audience Commodity, the Digital Labour Debate, Marxist Political Economy and Critical

Theory. Prolegomena to a Digital Labour Theory of Value. TripleC: Communication,

Capitalism & Critique 10(2): 692-740.

Fuchs, Christian and Sebastian Sevignani. 2013. What is Digital

Labour? What is Digital Work? What’s their Difference? And Why Do These

Questions Matter for Understanding Social Media? Triple C 11(2): 237-293.

Gauntlett, David. 2011. Making is Connecting: The Social

Meaning of Creativity, from DIY and Knitting to Youtube and Web 2.0. Cambridge:

Policy.

Goldate, Steven. 1997. The Cyberflâneur. Art

Monthly.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday

Life. New York: Ancor.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. The Structural transformation

of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Studies in

Contemporary German Thought). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Hardt, Michael. 1999. Affective Labour. Boundary 2:26:

2.

Hardt, Michael and Antonion Negri. 2004. Multitude: War and

Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin.

Hodges, Sara and Kristi Klein. 2001. Regulating the costs of

empathy: the price of being human. Journal of Socio-Economics 30: 437-452.

Internet World Stats. 2012. Facebook Users in the World.

Accessed December 15, 2013. http://www.internetworldstats.com/facebook.htm

Jenkins, Henri. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New

Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Kellner, Douglas. 2009. Towards Critical Media/ Cultural

Studies. In Media/ Cultural Studies: Critical Approaches, edited by Rhonda

Hammer and Douglas Kellner. Bern: Peter Lang.

Lazzarato, Maurizo. 1996. Immaterial Labour. In Radical

thought in Italy, edited by Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt. Minneapolis, MN:

University of Minnesota Press.

Lipps, Theodor. 1979. Empathy, Inner Imitation and

Sense-Feelings. In A Modern Book of Esthetics: An Anthology, edited by Melvin

Rader. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. 1845/46. The German

Ideology. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Mead, George. 1967. Mind, Self, & Society: From the

Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Edited by Charles Morris. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2012. The Death of the Cyberflâneur.

New York Times. Accessed December 3, 2013.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/05/opinion/sunday/the-death-of-the-cyberflaneur.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&

Shaya, Gregory. 2004. The Flaneur, the Badaud, and the Making

of a Mass Public in France, circa 1860-1910. The American Historical Review

109 (1): 41-77.

Shirky, Clay. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of

Organizing without Organizations. London: Penguin Press.

Scholz, Trebor. 2010. Facebook as Playground and Factory. In

Facebook and Philosophy, edited by D.E. Wittkower. Chicago and La Salle: Open

Court.

Stotland, Ezra. 1969. Exploratory Investigations of Empathy. In

Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol 4), edited by Leonard

Berkowitz. New York and London: Academic Press, 271–314.

Stueber, Karsten. 2013. Empathy, The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy (Summer 2013 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta. Accessed December 1.

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/empathy

Tapscott, Don and Anthony Williams. 2007. Wikinomics: How

Mass Collaboration Changes Everything. New York: Penguin.

Thrift, Nigel. 2005. Knowing Capitalism. Thousand Oaks:

Sage Publications.

Toffler, Alvin. 1980. The Third Wave. New York:

Bentam.

Turner, Graeme. 2004. Understanding Celebrity. Thousand

Oaks: Sage Publications.

Vejby, Rune and Dylan Wittkower. 2010. Spectacle 2.0? In

Facebook and Philosophy, edited by D.E. Wittkower. Chicago and La Salle: Open

Court.

White, Edmund. 2008. The Flaneur: A Stroll Through the

Paradoxes of Paris. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

About the Author

Ekaterina Netchitailova

Ekaterina is a Doctor of Philosophy. Her thesis focussed on

Facebook by using critical media/cultural studies and where Facebook was analysed

both in the context of capitalism and also as a part of popular culture.