1. Introduction

Over the last decade, mediatisation has emerged as a central concept and approach used by many media and communication scholars to explain “changes in practices, cultures, and institutions in media-saturated societies” (Lundby 2014, 3). Along with the changes to the media, which are defined as technologies and means of communication, societies as such are purportedly transforming as well. This is because media have become ubiquitous and grown in influence; the power they have gained in this process has seen them become the cause of social change (Lundby 2008, 105). Mediatisation assumes that these transformations are so profound that it is only possible to speak of “the long-term, large-scale structural transformation of relationships” (Hjarvard 2013, 3). In short, the aim of the approach is nothing less than remarkably ambitious: to explain the apparently epochal changes that the media and communication technologies are bringing to society.

Notwithstanding that mediatisation is becoming more important in the international academic environment, it has yet to be subjected to an in-depth analysis in the Slovenian research community, let alone serious criticism. This means understanding of the approach remains conceptually limited and restricted to unreflected use of the term. Despite these limitations, the concept has passed into general use in local academic publishing.[1]

This text has two aims. First, to introduce mediatisation and provide an empirical and theoretical critique of it. This is also the primary aim of the paper given that the apparent validity of the basic premises of the approach is such only if we remain on the surface of the relations that media are embedded in. Second, to modestly fill the research gap in the field of the political communication of Slovenian political parties and to make sense of their views, largely with the help of media sociology and the political economy of communication. These two approaches also serve as the basis for a critique of mediatisation.

Even though mediatisation today stresses the overarching transformations of society, it was mainly focused on the changes the media have brought to the way politics functioned in the early days of the approach. The systematic study of the public communication of institutional political actors, notably political parties and politicians, has of course been a constant feature of academically developed environments for at least three decades and thus predates studies of mediatisation. Yet, the Slovenian research community has produced surprisingly few empirical analyses largely focused on the relationship of these actors to mediated communication. The paper is empirically based on in-depth semi-structured interviews with central representatives of seven parliamentary and three extra-parliamentary Slovenian parties or party coalitions. These actors formed part of the 7th session of the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia between 2014 and 2018.[2] In the interviews, political actors presented, among others, their views on the media, their assessment of the social impact of the media, and the role these institutions play in the public communication of their own parties. The interviews revealed that the interviewees’ interpretations are internally contradictory when it comes to the role of the media. This is why I critically contrast the views of the interviewees with their own activities and statements and how – according to them – other actors influence power relations in public communication.

I do not rely on empirical data with the aim of a comprehensive analysis of the attitudes held by Slovenian political parties to the media. I must stress this is by no means the primary purpose of the paper. The answers and interpretations provided by the interviewees are mostly of an illustrative nature, explaining why I deliberately avoided a detailed and systematic presentation of the empirical data. What I want to show as clearly as possible is why at first glance some of the assumptions of the mediatisation approach are indeed very convincing, but a holistic analysis then reveals its serious limitations. The interviews thus offer an opportunity for an empirically grounded critique of mediatisation. They shed a different light on the straightforward assumption of the power of the media as it is at least implicitly present in most explanations of mediatisation. As I note in the paper, the central problem with mediatisation is that it wants to make assumptions about the growing social influence and power of the media without ever addressing the question that necessarily follows from this: What are the broader power relations in capitalist society, and how are they changing? The power of the media is therefore understood in a completely abstract manner, with the media not being analysed as a part of the social totality.

2. Mediatisation as a Central Concept in Media and Communication Studies

Various authors such as Lundby (2009), Hepp (2012), Ampuja, Koivisto and Väliver-ronen (2014), Stanyer and Deacon (2014) and Krotz (2017) state that mediatisation has become a central concept in research on media and communication. This is undoubtedly true at least for European researchers since the approach originates from the German, Nordic and Central European academic communities. Mediatisation has also found a home under the umbrella of the European Communication Research and Education Association (ECREA). After May 2011, the association initially hosted a temporary working group under this name, while in 2015 the group was given full status and successfully transformed itself into one of the 21 permanent sections.

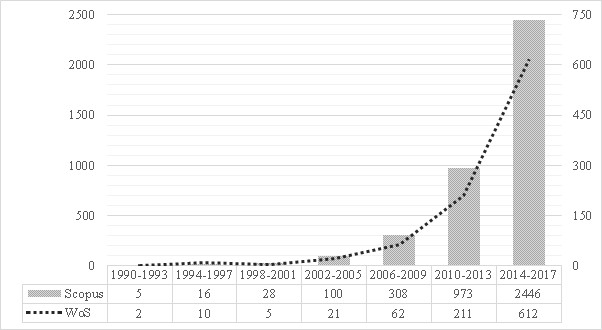

The rising status of mediatisation in research is also shown by the remarkable increase in the number of publications containing this term. For example, the number of such academic works in recent years (Figure 1) included in the referential citation indexes Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) is difficult to overstate. While by 2000 only 38 (Scopus) and 19 (WoS) papers with the term mediatisation were indexed, there has been almost exponential growth in the number of papers recorded since then. Between 2000 and 2017, Scopus indexed 3,843 individual publications that included the term, while WoS included 908 such works. In each case, the majority of publications containing the term was published after 2013.[3]

Figure 1: Presence of the term mediatisation in academic works indexed in Scopus and WoS since 1990. The search was conducted using the terms mediatisation and mediatization in the query by including all possible fields available in the databases.

2.1. Mediation and Mediatisation

In light of the above, there is no doubt that mediatisation has in the span of just a few years become a significant part of the academic mainstream. Some even refer to it as “an integrative concept” (Couldry and Hepp 2013, 192) for media and communication studies. Mediatisation should be distinguished from mediation, which is a related concept in media and communication research that denotes “the use of the media for the communication of meaning” (Hjarvard 2013, 2). It can also be used to “describe people or organisations that communicate via media” (Krotz 2017, 106) or simply a variety of relations with the media. For Lundby (2014, 7), the basic difference between the two concepts is that “mediated communication turns into a process of mediatization when the ongoing mediations mould long-term changes in the social, cultural, or political environment. Mediatization is change”.

Unlike mediation, which is also used outside of media and communication studies to refer to various forms of negotiation or intermediation, and can thus be used to refer to a very broad range of social processes, mediatisation has become established as a more limited concept in the last decade. In mediatisation, the social role of the media is not restricted simply to the communication cycle of the sender, the message and the audiences, which is the typical focus of media and communication research, but is also “concerned with the long-term structural change in the role of the media in culture and society” (Hjarvard 2013, 2, emphasis by the author). In mediatisation, media are defined as those who actively transform other spheres. In contrast, mediation does not presuppose such a socially transformative activity, it is “merely a descriptive statement” (Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999, 250) that is essentially neutral in nature (Ampuja et al. 2014, 112).

2.2. Subordinating Politics to the Media Logic

In the early days of the mediatisation approach, analyses of the influence of the media were principally concerned with their relationship to politics. This remains one of its central research topics (see Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999; Schulz 2004; Strömbäck 2008; Hjarvard 2013, Ch. 2; Landerer 2013). The claimed changes in politics due to the media are best illustrated by Mazzoleni and Schulz (1999, 250) who define mediatised politics as “politics that has lost its autonomy, has become dependent in its central functions on mass media, and is continuously shaped by interactions with mass media”. In this respect, the media have become “the most important arena for politics” (ibid.) and thus perhaps even the central political institution (see Ampuja et al. 2014, 112).

This approach to mediatisation largely relies on the operation of the ‘media logic’ to which various social institutions, including politics, must supposedly adapt their own activities.[4] The media are assumed to have their own rationality and rules of operation, which they have consequently started to extend to other institutions, spheres and social systems. These spheres must internalise the media logic and submit to it in the way they work in practice, or they risk their own decline. Politics, for instance, can no longer operate according to its own logic, i.e., political logic, but must begin to adopt a logic which is alien to it, a logic that is distinctive for the media.

The concept of media logic was originally defined by Altheide and Snow (1979). They provided a critique of previous analyses of the media, while demonstrating how, “as a form of communication, media change our way of ‘seeing’ and interpreting social affairs” (ibid., 9). They were interested in the formats specific to the mass media and explored what their impact was, indicating that American culture is in essence becoming a media culture, with other institutions bound to adapt to these changes. In their study, they found that “political life is being recast to fit the demands of major media” (ibid., 136) and is becoming an “extension of media production” (ibid., 146; cf. Ampuja et al. 2014, 112).

Although the study is now four decades old, the definition of media logic remains fundamentally the same today. Altheide (2004), for example, stresses visuality and drama as important formulas of entertainment-based journalism. In so doing, “the format and logic of newsworthy information shape the nature of discourse itself” (ibid., 295). The typical rules and routines in the production of mediated communication, which may well also be called “storytelling techniques”, include “simplification, polarization, intensification, personalization, visualization, stereotyping, and particular ways of framing the news” (Strömbäck and Esser 2009, 213).

In many ways, the concept of media logic is related to tabloidisation and infotainment. However, both of these concepts are – especially in critical approaches – closely linked to the economic mechanisms that influence how the media functions and its focus on the spectacle (e.g., Thussu 2008). Such critical connotations are much less noticeable in the case of media logic (Landerer 2013, 243). Moreover, this logic is generalised to the media overall, leading Landerer (2013) to conclude that it would be more accurate to speak of a commercial media logic. The normative role of the media is fundamentally different from that assumed in the media logic, and in this respect in Landerer’s view both media and journalists oscillate between two extremes: commercial and normative considerations, with the former often prevailing in capitalist society.

2.3. The Strong and Weak Approaches to Mediatisation

It is precisely the (non-)existence of the media logic that has become a key point of theoretical disagreement in the internal debates on mediatisation. Authors like Krotz (2017, 110) or Hepp and Couldry (2013; Hepp 2012, 2-8) argue that media logic is a reductionist concept. Due to the heterogeneity of media, they argue it is by no means possible to speak of a single media logic, but at best of several media logics. They also emphasise that it is impossible to speak of a linear and homogeneous media influence since social change is thought to be more open and complex. These internal critiques have also identified problems with digitalisation and new technologies because they are not addressed in a sufficient manner by the media logic.

These considerations have led to a differentiation between two understandings of mediatisation: an institutionalist approach on the one hand, which is chiefly based in journalism studies and approaches related to political communication research, and on the other hand a social-constructivist approach grounded mainly in cultural studies, which highlights that the use of media also transforms social relations (Hepp and Couldry 2013, 195-198). Although both approaches are supposed to be about long-term changes, in the former these periods span several decades, while in the social-constructivist approach, they potentially span even several centuries (Lundby 2014). Such a long span arises from the fact that mediatisation is considered to be a meta-process (Hepp 2012; Krotz 2017) comparable to other key modern meta-processes such as globalisation, individualisation or commodification. Further, as ubiquitous technologies, media have different properties that condition the ways in which they are used according to the social-constructivist approach, and therefore transform different fields, relationships and, above all, people’s everyday lives (Ampuja et al. 2014, 116-120). Even though the social-constructivist approach resists this label, the conditioning is in fact an assumption close to the technologically deterministic theories of Marshall McLuhan, Harold Innis or Neil Postman (ibid.).

In a critique of both approaches, Ampuja and co-authors (2014) distinguished between the strong and weak forms of mediatisation (Table 1). According to them, the weak approach wants to get rid of the linear causality present in the strong approach as it adopts the mediatisation logic. Yet, while it ostensibly avoids oversimplifications, the weak approach opens up a host of new problems. In addition to an inadequate definition of what the medium is, it unsuccessfully attempts to introduce multi-causality. The approach is also unable to explain the relationship between the various meta-processes, which mechanisms manage to establish mediatisation or what kind of causality originates from mediatisation (otherwise it simply depends on the remaining processes in society for its existence) (cf. Deacon and Stanyer 2014; Bilić 2019).

|

|

Paradigmatic starting |

Central |

Fundamental presuppositions of the approach |

Primary field of study |

Common points of the two approaches |

|

Strong |

Institutionalism |

Media logic |

• Institutions in society adapt to the media, their rationality and rules of operation • Relative media autonomy |

Political

actors and |

• Increased influence and power of the media • Media as a force of social change • The ubiquity of media in society, everything is becoming mediatised • Non-normative, • Long-term nature of the process (difference: decades vs. centuries) |

|

Weak |

Social |

Social |

• A central meta-process in modernity, but not more important than other meta-processes with their own logic • Media with a variety of characteristics that condition their use; due to their ubiquity, parts of society are transformed in different ways; boundaries are collapsing |

Contextual

study of |

Table 1: Differences between the strong and weak approaches to mediatisation. Starting points in the works cited in subsections 2.2 and 2.3, especially in the paper by Ampuja et al. (2014).

It is accordingly not even clear whether the weak approach is theoretically capable of establishing any unambiguous explanations of how social reality changes (ontological level) and what exactly is supposed to be the explanatory power of mediatisation (Ampuja et al. 2014, 120). If it is simply a descriptive concept designed to identify the increasing proliferation of media, then “this process can be approached from various theoretical perspectives, which bear no necessary relation to the idea that the media have any independent power (technological or otherwise) to cause and explain that spreading”, as Ampuja and co-authors stress (ibid.). Although both approaches emphasise the long-term nature of these changes, these changes have also hardly been addressed empirically in individual studies (Deacon and Stanyer 2014, 1037).

3. Limitations of the Mediatisation of Politics and Parties’ Political Communication

Irrespective of the many ambiguities and differences between the two approaches to mediatisation presented in the above section, authors in the mediatisation approach share the conviction of the increased power of the media, which is changing the internal dynamics of different spheres in society. The strong approach, in this context, points to the distinct and essentially linear influence of the media on the functioning of non-media institutions and spheres. Due to the differences between approaches, I will focus my critique primarily on the strong approach in the following sections since its basic assumptions are stated the most clearly. The strong approach also places most of its attention on the impact of the (news) media on the political institutions that interest me in this paper. Although most of my criticisms will refer to the strong (or institutionalist) approach, in many respects they also apply to the weak approach to mediatisation.

3.1. “The media dictate the topics and create politics”

Strömbäck and Esser (2009, 219) define the influence of the media on other institutions as an “interventionist media logic” and portray it as an “engine of the mediatisation of politics”. This notion is directly linked to the media logic, and some research on political elites in European countries has also relied on assuming this kind of role of the media in the functioning of politics. This research has revealed that politicians do indeed perceive the media as central institutions and main agenda-setters in politics (Val Aelst et al. 2014, 207), as the media logic thesis contends.

With these findings in mind, it is not surprising that views on the increased power of the media can also be found amongst the interviewed representatives of Slovenian political parties. In many cases, the views held by the interviewees almost entirely overlapped with the premises of the strong approach to mediatisation. For example, when commenting on the functioning of the largest and most influential commercial television station in Slovenia, a representative of a smaller centrist political party noted:

“The media is no longer the objective reporter that it is supposed to be. They are neither a mediator nor an analyst, but have become an active creator of politics. The media dictate the tempo of topics. /.../ What worries me the most is that some of the media have realised that their power is not in reporting, in analysis and so on, but in the power to create politics, which is otherwise the preserve of those who have been voted in at elections”. (R. Jakič, ABA)

Comparable views were expressed by representatives of other parties:

“The first 2 minutes on POP TV are crucial for politics in Slovenia, /.../ and this is also the average length of the Slovenian voter, how much he/she deals with politics per day. /.../ From 2007 to 2008, we did everything we could to get into this position [in the first 2 minutes, JAP], so we were an alternative to SPD at the time. At that time, we were absolutely adapting to this framework with all of our stories. We were – empirically or not, it’s hard to say – but /.../ we were working with our American advisers who are now working for Hillary Clinton, and that was one of their most useful pieces of advice when they were scanning Slovenia”. (U. Jauševec, SD)

“Media play an important role, I’ll even say /.../ a little too important, because everything is now set to the likeability and image of the media”. (B. Simonovič, DePPS)

“The media act according to their own inertia, and in addition they interpret the story in their own way. In this way they shape our destiny, they provide the frames within which we can communicate”. (N. Janovič, UL)

Interviewees generally perceived both the influence and the role of the media in a negative light. Many held at least an implicit view that the media were usurping functions that belonged to the political realm, and some also had a negative attitude toward the media for being aggressive or overly critical of their political party. The latter was particularly noticeable in the case of the SPD party representative. The interviewee, for instance, noted that the media “have a big role and also a lot of power”, which they “often don’t use positively” (A. Jeraj, SPD). Still, similar views were also expressed by other interviewees.

The interpretations and reasons provided by the interviewees are thus in line with the central presumption of the strong approach to mediatisation. But is this enough to conclude that this thesis is in fact correct? As I demonstrate below, the answer must unequivocally be in the negative. The most basic problem lies in the simple fact that the perceptions of politicians do not necessarily correspond in any meaningful way to reality. For example, research on who actually influences the agenda-setting in politics has arrived at opposite conclusions (see Van Aelst et al. 2014, 207; cf. Franklin 2003; Schudson 2011, 14-15). This makes it necessary to shed light on this problem from other viewpoints.

3.2. The Crisis of Political Legitimacy and the (Non-)Influence of the Media

Even though mediatisation avoids being a normative approach (see Strömbäck 2008, 229), it is safe to claim that when it comes to the assumptions connected to the media logic they describe a process that implies unwanted changes in relation to politics. In the paper cited above, Strömbäck and Esser (2009, 220) for instance claim that “increasingly, the constructions of reality conveyed by the media and shaped by media logic matter more than any actual reality, as it is the only reality to which people have access and thus treat as real”. Given that nowadays the same authors highlight the rise of populism and the crisis of liberal politics (see Aalberg 2017), I will not be making a bold claim if I write that a significant part of media and communication studies attributes at least some responsibility for these processes to the workings of the media. Mazzoleni and Schulz (1999) suggested early on that mediatisation could undermine democracy, while Mazzoleni (2014) later directly linked populism to mediatisation.

Noting how definite the assumptions present in the mediatisation approach are, one would reasonably expect that the media’s influence on politics would be brought to the attention of the rest of the disciplines in the social sciences, especially when they are dealing with the ongoing legitimacy crisis. Yet media are almost completely absent from these studies. Streeck (2014), who is predicting the end of democratic capitalism, does not devote a single word to the media in his analysis. Similarly, Crouch’s (2004) thesis on post-democracy attributes this trend mainly to the rising social inequalities, the growing influence of corporate elites and the trivialisation of politics (where it but briefly touches on the media). Mair’s (2013) findings on the hollowing out of Western democracy due to the crisis of mainstream politics also barely mention the media.

The reasons the works of these authors regularly neglect the media may be found in their disciplinary closedness and, at the same time, in the marginal status of the media and communication research in social sciences. However, even if we take these quite plausible explanations into account, this still seems like a noteworthy signal of the possibility that the role played by the media might not be as straightforward as mediatisation assumes. Is it possible that these authors would have otherwise neglected them to such an extent, thereby missing out on a factor that could play a vital role for their topic?

3.3. The Media Not Being a Dominant Institution in Political Communication

In contrast to these authors, Della Porta (2003, 80-85, 141-148) devotes considerably more space to the media in her Foundations of Political Science, especially pointing to the spectacularisation and personalisation of politics, its adaptation to media formats, and the creation of what she calls media parties. Given the importance of Silvio Berlusconi in Italian politics, this is not a surprising development, but what seems more important is that Della Porta does not present this relationship in a linear way. Political actors play an active role and deliberately use the media for their own ends. Yet, in the strong approach to mediatisation politicians are presented as almost hapless and passive victims forced to surrender to the media’s power. By so doing, they are either intentionally or inadvertently absolved of responsibility for the social status quo. Mazzoleni’s (2017, 140, emphasis by JAP) claim that “no doubt politics has been increasingly ‘swallowed’ by the entertainment, commercial, sensationalist imperatives” of the media suggests precisely this passivity. In the Italian context – from which both Mazzoleni and Della Porta come – such a thesis could at the very least be viewed as somewhat peculiar. Berlusconi, after all, actively subjugated the media system to his personal political needs.

McNair’s (2007) introductory textbook on political communication deals with these issues in a similar fashion to Della Porta. For him, there is no doubt that the media have become crucial for politics. However, he also argues that this is an interactive relationship in which both parties act as active agents, and both are also dependent on the other. In this relationship, politics relies mostly on political marketing to achieve its goals (cf. Landerer 2013), a tendency that is also explicitly and strongly present among the interviewed Slovenian party representatives (see Prodnik 2016).

The very active role of Slovenian parties and politicians in their relations with the media is also manifested in other ways apart from political marketing and the use of public relations (ibid.). Although the interviewees underscore the power of the media, they are aware of both the logic of how the media operates and also how to (ab)use it for their own gain. Most interviewees spoke very candidly about this either in the context of branding politicians and political parties (ibid.), in their everyday work with journalists through press conferences, press releases and interviews (R. Ilc, NSi), in the need to maintain “very good relations with the media” (T. Romih, SPS) or in the constant adaptation of their statements for the news media, making their main points shorter and repeating them (e.g., soundbites), to make them better suited for the media who then amplify them. According to one interviewee, messages should be “clear, concise, short, understandable” (B. Simonovič, DePPS). Similar tactics are also used by other parties:

“It’s like that with soundbites: yes, they are pragmatic, /.../ it’s a purely tactical thing, just to get attention that we don’t get any other way. /.../ We try to get our content into the media, but at the same time, if we think it’s necessary to respond to an insert produced by the media, we at least spin it, or try to spin it, so we give it our own twist”. (N. Janovič, UL)

3.4. Journalistic Sources and Power Relations between the Media and Politics

This relatively evenly balanced, but above all complex relationship, according to which it takes two to play, has been analysed in detail in the sociology of the media over the last five decades (see Schlesinger 1990; Tumber 2014, 65-69). Schudson (2011, 147) for example stresses that political and media institutions are “so deeply intertwined, so thoroughly engaged in a complex dance with each other, that it is not easy to distinguish where one begins and the other leaves off”. The fact that this is a complex relationship, where solely a reductionist approach would claim that only one of the parties involved has the power to shape the public agenda, has also been pointed out by several other studies (see Schlesinger 1990; Franklin 2003; Vobič et al. 2016). Perhaps the most famous definition of this relationship between the media and politicians as information sources was given four decades ago by Herbert Gans:

“The relationship between sources and journalists resembles a dance for sources seek access to journalists, and journalists seek access to sources. Although it takes two to tango, either sources or journalists can lead, but more often than not, sources do the leading. /…/ The source–journalist relationship is therefore a tug of war: while sources attempt to ‘manage’ the news, putting the best light on themselves, journalists concurrently ‘manage’ the sources in order to extract the information they want”. (Gans 2004/1979, 116-117)

Interestingly, a similar illustration to that provided by Gans was used by one of the interviewees who compared the politicians-media relationship to a game in which resourcefulness is important. In his opinion, this was something that “every politician” (R. Ilc, NSi) was doing. Although this relationship is fundamentally important in the sociology of the media, where it has been thoroughly researched empirically, it is not inconsequential that it is largely ignored by the mediatisation approach. As Williams (2005/1978, 55-60) would argue, the media, among other things, facilitate the amplification of voices in society, and this is one of the core goals of sources when they attempt to use media to pursue their particular goals (cf. Schlesinger 1990, 74-76). If we restrict ourselves to political actors, they want to instrumentally increase the reach and hence the potential impact of their messages and, by so doing, they can use different tactics in their relations with the media (cf. Franklin 2003). This raises the paradoxical question of whether we are still talking about the power of the media or in fact the power of those who author the messages, i.e., the media sources, with their influence further increasing when messages are transmitted through the mass media.

Schudson (2011, Ch. 7) notes that when answering this question it is necessary to analyse who the central journalistic sources are in the news. Today, they include government officials, the state and political decision-makers, with all being perceived as legitimate and routine sources. They offer a regular flow of information via various government-initiated events, such as press releases, public speeches and press conferences, together with the legislative process and other up-to-date developments in the parliamentary bodies (cf. Schlesinger 1990, 69-76; Curran 2019, 191). Messages issued by public relations units are also a key source for journalists since all organisations (especially corporations) wish to control their public image, with the number of people around the world professionally working in PR constantly growing (cf. Dinan and Miller 2007; Davies 2011). Schudson (2011, 14, 142) uses the term “para-journalists” to describe these actors since they try to produce information for the media that largely resembles typical journalistic news in their format, with the aim to pass through the journalistic gatekeeping process and be published in their original form.

For Schudson, the production of news today is therefore ever more the result of a relationship between journalists and para-journalists. The worrying dominance of mainstream politics and PR materials as the main sources of information in the news media has been confirmed by several studies. They have also highlighted the rise of recycling and copy-paste journalism in which journalists use pre-written, often PR, information (see Franklin 2003; Lewis et al. 2008; Davies 2011; Franklin 2011; Tumber 2014, 69). This led Davies (2011) to refer to the media as news factories, while Curran (2019, 191) argued that reliance on elite sources leads to a blurring of the distinction between democratic media systems and those specific to authoritarian states.

4. Between the Power of the Media and the Subordination of the Media Industries to the Market and Politics

The assumptions about the increased power of the media made by the mediatisation approach are distinctly abstract compared to the analyses offered by the sociology of the media. This makes it necessary to ask a more concrete question: in relation to whom or what is the power of the media supposedly increasing? In the case of the mediatisation of politics, the answer can only be: in relation to politics. However, this automatically raises new dilemmas that the mediatisation approach does not address, despite it claiming to be a holistic approach (see Livingstone and Lunt 2014, 711; Murdock 2017, 120). Indeed, the relationship between politics and the media must necessarily include: first, an understanding of politics as a crucial, but not exclusive source of information (see sections 3.3. and 3.4.); and second, an analysis of these two institutions as parts of the broader social totality. Media and politics, after all, do not exist in isolation from the rest of society but are influenced by other institutions, processes and relations.

This means that mediatisation – perhaps inadvertently and unintentionally – opens up a debate about the current power relations in capitalist society and who controls the course of public communication in it. For the sociology of the media, the question about the “nature of information management in society” should necessarily touch upon the “conditions of unequal power and therefore unequal access to systems of information production and distribution”, as argued by Schlesinger (1990, 82). However, mediatisation completely avoids any serious discussion of power relations in society.

Inequalities and hierarchies in access to the media were already briefly highlighted by Gans (1979/2004, 119) in the aforementioned study. For him, it was only “in theory [that] sources can come from anywhere, in practice, their recruitment and their access to journalists reflect the hierarchies of nation and society”. Schudson (2011) believed there is consequently no doubt that in mediated communication it is not the media as such that have influence and power, but in actual case their sources. Media reporting hence primarily includes the views of those groups holding the most power in society, meaning the diversity of voices in the public sphere is inevitably limited.

Compared to mediatisation, the sociological perspective provides a considerably different viewing point, one that forces us to also include in our further analyses various debates on the growing influence of corporate PR and lobby organisations (see Miller and Dinan 2007), studies on the role of propaganda in capitalism (see Zollman 2017), and, finally, the organisation of the media, i.e., the fact that these are for the most part capitalist industries operating on the market (Prodnik 2014, Ch. 7).

4.1. Autonomy or Heteronomy of the Journalistic Field (the Bourdieu Paradox)

One of the most important sociologists to have paid attention to the power of the media is undoubtedly Bourdieu (1998a; 1998b; 2005), who considered the impact of the journalistic field in relation to the political field and the field of cultural production. Although the autonomy of all fields is relational, media, which according to Bourdieu (1998a, 76) at the time had a monopoly on the dissemination of public information, have eroded the autonomy of the other two fields; they have invaded them with the expectations that are distinctive of the journalistic field (ibid., 74).

At first sight, Bourdieu’s conclusions largely overlap with the assumptions made by the strong approach to mediatisation. Yet, in addition to the media’s influence, mediatisation also presupposes the increased autonomy of the media (see Deacon and Stanyer 2014; Ampuja et al. 2014, 115). Hjarvard (2008, 110, 116; 2013, Ch. 1) connects media autonomy to their emancipation from the control of political parties (in the 19th century) and public monopolies (in the 20th century). As a result, according to Hjarvard journalists are now able to follow professional standards. A similar claim concerning increased autonomy was made by Strömbäck and Esser (2009, 209, emphasis by authors), who somewhat enigmatically claimed that “mediatisation means that the media form a system in its own right, independent although interdependent on other social systems such as the political system”.

Still, the similarity between the two approaches exists only on the surface. For Bourdieu (1998a, 54), the fact that the media are increasingly influencing other fields does not automatically translate into increased autonomy for the journalistic field itself, but quite the contrary. Paradoxically, this is a field that is distinctly heteronomous because it is increasingly constrained by both market pressures and politics. As Bourdieu notes, the “commercial element” in the journalistic field “weighs much more heavily on it than on other fields” (Bourdieu 2001, 70). Journalism is “increasingly subject to direct or indirect domination by the market model” (ibid., 74), as it “is permanently subject to trial by market, whether directly, through advertisers, or indirectly, through audience ratings” (ibid., 71).

As Bourdieu knew himself, he did not say anything that was not already widely recognised and that actors working in the media did not also know themselves (see Bourdieu 1998b, 70-71). The same also applies to many of the interviewed politicians:

“It all depends on the ratings and then, if necessary, constructs can be made, just so that the viewership ratings are big. /…/ The media environment is like this: viewership, and you don’t care about anything else. ‘I want an answer, now!’. And if you don’t give it, he’s already threatening you: ‘So, we’ll say you don’t want to say anything to us, because you have something to do with it’. Then they link you to how you’re supposedly supporting the management of a firm, even though it has nothing to do with anything”. (E. Kopač, MCP)

“I think that’s the problem [laughs], they are businesses, they are selling viewership, ratings, circulation...”. (B. Simonovič, DePPS)

Bourdieu identified the ratings imperative and the outcomes of this tendency especially in television, which he saw as the most heteronomous part of the journalistic field. Journalists are in constant competition to be the fastest in breaking the news, in getting well-known and reputable sources (Bourdieu also identified the dominance of elite sources) and exclusive information, which in fact produces uniformity. Even 20 years ago, the precarity among journalists and extreme time pressure on news production had already intensified, as reflected in both the pace of their work and the increasing amount of news they had to produce (Bourdieu 2005, 42-43). One interviewee, for instance, highlighted a more extreme consequence of journalistic precarity:

“But the crucial aspect lies in this: who controls these media? Are they really at the service of the public, or at the service of someone else? That is it. And today, with all these precariously employed journalists, look, they tell you: €500 and he/she will launch whatever story you want. That’s the problem, you know. The function of the media is to inform the public and also to defend the public and so on, but it’s just a shame if their power /.../ is used for something else”. (E. Kopač, MCP)

All of these factors in news production contribute, among other things, to a limited number of sources since journalists simply do not have the necessary time to build their network of contacts and to then maintain it (cf. Gans 1979/2004; Davies 2011; Schudson 2011). Above all, this leads to an overall lowering of journalistic standards.

4.2. Media as Capitalist Industries

The pressure from audience ratings comes from the fact that media are typically capitalist companies which, by virtue of their market presence, compete with other media for audience attention (Landerer 2013, 244; Prodnik 2014, Ch. 7; Hardy 2014). This tendency was particularly prominent on television in the 1990s, which was a key source of demagogic depoliticisation (Bourdieu 1998, 74), but today it has been reinforced and extended to the rest of the journalistic field, including newspapers, to which Bourdieu attributed the greatest degree of autonomy. With fast-declining circulation and consequently declining ad revenues, the market pressure on newspapers is only growing with the Internet and social media. As a result, there is quite a broad consensus amongst scholars pointing to a deep crisis of quality journalism manifested in lay-offs of journalists, precarisation, media closures, commercial pressures, and increased work commitments for journalists, which further add to the reliance on PR messages and other pre-written information (see Franklin 2011, 91; Vobič 2015; Curran 2019, 192; Pickard 2019, 154). Vobič (2015, 38) critically emphasised that the ever-greater profit pressures on the owners of the media make it “increasingly difficult to separate impoverished journalism from entertainment, advertising and political spin”. This is especially noticeable in those media systems that are completely subordinated to the market, for example the American one, which is also most acutely feeling the crisis of journalism (Benson 2014, 36).

Even though the market pressures on the media were – at least in its basic outline – self-evident even to some of the interviewees and have been dealt with in detail by political economy in communication (Prodnik 2014, Ch. 7; Hardy 2014, Ch. 4.), they are virtually ignored by mediatisation approaches (cf. Krotz 2017, 112-115). Accordingly, “this model pointedly ignores the primacy of capitalist dynamics in shaping the central contours of modernity”, which can be seen as the essential context of the mediatised society (Murdock 2017, 121). This led Murdock (ibid.) to use an amusing metaphor in his critique of mediatisation: “In their efforts to compile a more complete account of the elephant they have neglected to ask who owns and trains it and what it is doing in the room”.

In recent decades, media have been gaining significant economic power, merging into transnational corporations that are among the largest companies in the world in revenue terms. In national and local contexts, media markets are increasingly being monopolised, concentrating communication power in the hands of a few of the biggest media outlets. The decision to allow the almost complete liberalisation of media and communications markets from the 1990s onwards has significantly contributed to this trend. While on the one hand, it has allowed acquisitions, mergers and the establishment of dominant media players, on the other, it has further added to market pressures, contributing to the dominance of sensationalism, tabloidisation and infotainment, which hold negative consequences for the quality of political debate and structurally make it impossible for the media to fulfil their normative role in society (ibid., 122-125; Thussu 2008; Landerer 2013; Benson 2014, 33; Hardy 2014, Ch. 4; Pickard 2019).

In this context, it is vital to note that such developments have not fallen from the sky, but have been enforced and endorsed by politics, which establishes the legislative and institutional framework within which the media and journalism operate. Namely: it was political decisions that contributed to the dismantling of the role of public media and the dominance of the market, even though empirical research shows how valuable publicly subsidised and public service media are: “Indeed, the overwhelming verdict of systematic discourse analyses is that non-commercial, government-subsidised media, including newspapers in many countries, are more critical, ideologically pluralist, and engaged with historical context and policy substance than purely commercial media” (Benson 2014, 31).

4.3. Instrumentalising the Media: Political Actors, Owners, and Corporations

Media can also be instrumentalised in a direct manner. Curran (2019) identifies censorship and political control, which are characteristics of authoritarian states, as among the fundamental factors in the crisis of journalism, in addition to their reliance on elite resources and the financial impoverishment mentioned above. In many studies that focus on journalism, these pressures are often overlooked due to their emphasis on Western liberal democracies, but they are nevertheless present in many political environments. They can include repressive legislation, editorial interventions from various governmental institutions, pressures connected to state licensing, control over communication infrastructure such as the Internet, or increased informal pressures on journalists and editors (ibid.).

Ownership pressures, often intertwined with political and economic interests, also have an influence on instrumentalising the media (see Deacon and Stanyer 2014). Rupert Murdoch is certainly the most notorious case – the media he owned clearly went hand in hand with his personal beliefs and political associates – together with Silvio Berlusconi, who used his control over the three biggest TV stations and the biggest newspaper in Italy to further his political career (Schlosberg 2017). The situation is no better in Central and Eastern Europe where media takeovers are linked to the influence of local elites (Štětka 2012). The influence of such actors and lobby groups was also highlighted by interviewees in Slovenia:

“When a certain media establishment decides to bring someone down in a political sense, it just brings them down, of course with the help of some political actors. You can’t escape this really”. (R. Jakič, ABA)

“As far as I know the Slovenian media landscape and the functioning of journalists, it is more or less all bought. And it is bought by – let’s face it – one broker-lobbyist, PR, I don’t know what kind of a company exactly. /.../ Media are never acting alone when doing this, they always do it in cooperation with lobbies or interest groups, which set the agenda for the media. Then the media run away with it. Politics is more or less a fellow passenger here, it sometimes adapts to these things, but definitely does not influence them, at least that is my impression”. (U. Jauševec, SD)

“A lot of the media is not from anyone, but the word on the street is, which journalist is going to do a story for you for so-and-so much [money] /.../. At that point, it actually becomes just an extension of a lobby, which wants to influence something”. (E. Kopač, MCP)

The structural (market pressure) and instrumental (politics, owners and lobbyists) pressures on the media deserve a more detailed discussion, which lies beyond the scope of this paper. There is no doubt, however, that the power relations between the media and the other powerful social actors are portrayed in a very different light if we have this in mind, instead of describing them in an abstract manner like mediatisation does. This observation could also be extended to the statements of the interviewees, which are internally inconsistent. The features and characteristics often mentioned in the interviews are not really about the power of the media as such – although all of the interviewees pointed this out in the conversations, as described in the first part of the article – but in fact relate to the instrumentalisation of the media. In these cases, actors and institutions are certainly not one-sidedly adapting to the media, it is instead the other way around: the media are moulded to fit their needs and adapt to them. When considering the power of the media, such forms of instrumentalisation certainly cannot be overlooked because – when combined with other factors – they significantly determine the conditions and inequalities in public communication.

5. Mediatisation as a Research Dead End?

At first glance, it might seem that by highlighting the central features of how media function, which are not investigated by mediatisation, this critique just becomes another thinly veiled attack on an approach that simply does not aim to study these aspects of the media. Not approaching some issues can be a completely legitimate stance since no approach is able to integrate all aspects and perspectives into its research, which would then provide us with a complete treatment of certain social phenomena. However, the problem with mediatisation is that it cannot really avoid analysing most of these aspects. If it ignores them, it becomes wholly unclear what media influence and power – and in relation to what – we are even talking about; if the approach itself highlights that it is holistic and wants to go beyond disciplinary divisions, it becomes quite obvious that it cannot ignore the role sources play in journalism, the institutional organisation of the media as capitalist industries, or the attempts to control public communication by various powerful social actors and institutions.

The problems of the approach mentioned above (especially in sections 3 and 4) are in fact a tangible demonstration of much deeper epistemological and theoretical failures of mediatisation, which the approach fails to address adequately or even avoids altogether. Leaving aside the ontological issues of causality and the nature of social change, which have already been criticised by other authors (see section 2.3), the issues with mediatisation touched upon in this paper can be analytically divided into three central problems:

(1) Mediatisation does not distinguish between the form and the content of mediated communication

The assumption that the growing power of the media is due to external actors adapting to the media logic wrongly assumes that these actors are necessarily losing power in this process and that the autonomy of the media is even rising in due course. The fact that various actors must adapt the way in which they communicate in order to increase the newsworthiness of their messages and thus amplify their reach in principle means merely that: adapting to the form. As noted by Schudson (2011, 13), one of the reasons “people tend to exaggerate media power” is because “they do not distinguish the media’s power from the power of the people and the events the media cover. That is, it is often not clear whether the media exercise much choice, freedom, or autonomy in producing news or simply relay to the general public what truly powerful forces tell them”.

The more relevant questions seem to be as follows: a) Does changing the form also affect changes in the content and, if so, in what way? b) Is it possible that the amplification of certain content by the media simply translates into strengthening the power of mainstream media sources, even though they have to adapt to the media with the form of their messages? c) What are the implications of the subordination of content to this spectacle form for democratic societies and political communication within them? d) Are the media still able to fulfil their normative role in democratic societies? The last two questions highlight a deeper problem: the declining interest in politics by the media in their reporting, which is mainly linked to their economic organisation and the ratings imperative, which constrains the autonomy of the media rather than contributing to it (see sections 4.1. and 4.2.).

(2) Mediatisation fails to make a proper distinction between public political communication and political activity as a whole

There is little doubt that public political communication is an essential part of the functioning of modern politics. However, it should be seen as unacceptably reductionist to equate political communication with the entirety of political activities, or even its most important parts. Even if we accept the assumptions of media logic, which suggest a relative loss of autonomy for politics, this applies at most to its public communication (and, as mentioned above, to the form of communication), and not necessarily to any other aspect of political activity. Has the transparency of all political activities increased? Have there been significant changes to political procedures, the policy-making process and political institutions because of the media? If so, in which aspects and over what period? The fact that “four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets” was already stressed by Napoleon Bonaparte two centuries ago, so is there anything new under the sun?

In other words: for the mediatisation approach, changes in political communication automatically imply changes in institutional politics and political activity as a whole, as there is no proper distinction between the two. It is true that public discourse can influence political action and that political speech can be defined as a political act in itself. Yet, while it may be true that political communication is also a political activity, it certainly does not follow that political communication alone is a political activity. The two cannot be conflated because the scope of political activity is much broader. And as Van Aelst and co-authors (2014, 207, emphasis by the authors) note: “The media logic definitely affects what politicians talk about, but there is much less proof that it influences what politicians actually do”.

It is worth recalling the critique voiced by the weak approach to mediatisation and also of some sociologists, who note that “there is no single media logic” (Benson 2014, 30). But does this also mean that it is impossible to identify a limited set of media logics according to the specific structure and organisation of (both the new and the old) media? (cf. Mazzoleni 2017, 139-142)

(3) Mediatisation ignores non-public parts of the political process and the inequalities in social relations of power

Since mediatisation focuses almost solely on the media, it overlooks several simple facts: first, much of political activity is not public, often intentionally so. Mazzoleni and Schulz (1999, 250) referred to this difference two decades ago: “There is no doubt that much ‘politics of substance’ is still practiced away from media spotlights, behind the scenes, in the discreet rooms of parliament and government”. But this was merely a side note in their text and became lost in subsequent discussions on the topic. Politicians are very interested in seeing some information become public and other information remain private, and they use different methods and techniques to exert control over the (un)availability of relevant information. It is also not necessarily the case that publicly released information is in fact aimed solely at the public; the aim may be to influence the activity of other actors in the political realm or in wider society.

Second, with growing social inequalities and the globalisation of capital, the influence of lobby groups and other forms of pressure is increasing. This means that the political process is influenced by many more actors and institutions than suggested by the reductionist models of mediatisation, which consider the relationship between politics and the media in isolation from wider society. When Crouch (2004) or Streeck (2014) write about the crisis of democracy, there could be good reasons why they fail to mention the media; for them, the more important issue could be the growing influence of capitalist markets over the rest of society and the consequent decision-making paralysis present in institutional politics today. Streeck (2014) even pessimistically observes that capitalism and democracy can no longer coexist because capital has been freed from its social obligations and completely escaped political control with financialisation and globalisation.

Many key political decisions are also in this case (or perhaps precisely with this reason in mind) taken away from the public eye. For example, the systemic nature of lobbying gives a significant advantage to the organised interests of industry and corporations. For them, lobbying is an investment that can be factored into the cost of doing business as it brings more favourable legislation and thus higher profits (Crouch 2004, 18). The USA is a story in itself, but even in Brussels, there are 25,000 lobbyists, with conservative estimates that approximately €1.5 billion is spent on lobbying annually. According to a 2014 study by the Corporate Europe Observatory, only the financial sector in the European Union spends €120 million on lobbying per year, 30 times more than all NGOs and trade unions combined (Lundy 2017, 10).

Third, politicians and the media are consequently not the only ones involved in the attempts to control public communication (see sections 3.4 and 4.3). These relationships are likely very hierarchical and include, inter alia, deliberate propaganda, corporate PR and various forms of pressure and control over the media. This makes it necessary to include social structures in any analyses of the media because there are “inequalities in the distribution of resources, material as well as symbolic” (Benson 2014, 27) in society that can be translated into public communication.

The fundamental problem with mediatisation is that it views all processes, institutions and relationships through the lens of the media. Lobbying influence or market pressures in public communication were also highlighted by the interviewed Slovenian politicians, but had the framework of the interviews been narrower and had they been asked exclusively about their relations with the media, the research findings would be quite different (see section 3.1). The narrowness of the mediatisation approach, which ignores the systemic framework in which the media function (Bilić 2019, 5), therefore brings with it obvious research problems and biases. In a way, the most appropriate way of describing them is to use the saying attributed to the psychologist Abraham Maslow: “If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail”.

6. Conclusion

Within the ongoing debates on mediatisation, there is anything but a consensus with respect to its meaning (cf. Bilić 2019, 3). This is clearly not an unusual situation in the social sciences, but in the case of mediatisation, the fact that the authors advocating it fail to even agree on the basics hardly helps its case in clarifying the confusion. For some authors, mediatisation for example seems to be just a concept (Couldry and Hepp 2013), for some, it is a process or even a meta-process (Krotz 2017), but at the same time also a specific approach (ibid.), for others it is even a “new research agenda” and simultaneously a theory (Hjarvard 2013, 1). On top of that, there are authors who consider it a field of research (Lundby 2014) and even a paradigm (Livingstone and Lunt 2014). If nothing else is certain, it should at least be clear that mediatisation cannot simultaneously be all of the above and that many authors use these labels quite indiscriminately, without making any proper distinctions between them.

No less problematic is the fact that mediatisation is now being applied to an increasing number of research fields, from the mediatisation of food, war and fashion to diplomacy, health, memory and childhood (cf. Deacon and Stanyer 2014, 1032-1033; Mazzoleni 2017, 137). According to Mazzoleni (ibid.), this raises serious questions about its explanatory power; if mediatisation is able to explain everything, it may in fact explain nothing at all. Livingstone and Lunt (2014, 719) similarly noted that “a considerable, and at times problematically diverse, body of work has been brought together” under the mediatisation banner. It is not irrelevant that in both cases these are internal critiques of the approach.

When adding the ontological, epistemological and theoretical problems to the conundrum, these internal critiques of mediatisation largely pale into insignificance. It seems that this eclecticism quite certainly indicates that in its ‘mature stage’ of development mediatisation is becoming a conceptual attachment that lacks any real content. In time, it may happen that mediatisation will mean nothing more than a descriptive and superficial inclusion of the media in the treatment of various areas of society. Deacon and Stanyer (2014) indirectly pointed this out in their critical review of the literature since mediatisation is generally not defined in the papers they analysed, with the use of the term analytically being very vague.

Like the rest of the social sciences, media and communication studies are characterised by fragmentation and specialisation, which has only intensified in recent years. However, this remarkable internal heterogeneity is a historical constant as the studies have drawn from a variety of social contexts, disciplines and theoretical approaches, and researched a highly diverse range of topics (and this diversity seems to be only growing with digitalisation). For media and communication studies, therefore, the question of whether it is even possible to speak of a truly separate and established discipline (or at most a field of research) is nothing new (Waisbord 2019). Even critics have accordingly stated that the aim of integrating the fragmented research of media proposed by mediatisation could be welcomed (Murdock 2019, 119). As mediatisation “places media analysis at the centre of all kinds of important developments” (Deacon and Stanyer 2014, 1033), it has also become strategically important for some researchers in constructing the identity of the field and its academic promotion, which ultimately can also be linked to pragmatic considerations of research funding (ibid.; Ampuja et al. 2014, 121). Yet such instrumentalisation of research includes considerations that do not necessarily have as its goal an understanding of the role of the media in broader society.

References

Aalberg, Toril, ed. 2017. Populist political communication in Europe. London: Routledge.

Altheide, David. 2004. Media Logic and Political Communication. Political Communication 21 (1): 293-296.

Altheide, David and Robert Snow. 1979. Media Logic. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Ampuja, Marko, Juha Koivisto and Esa Väliverronen. 2014. Strong and Weak Forms of Mediatization Theory. Nordicom Review 35 (Special Issue): 111-123.

Benson, Rodney. 2014. Strategy Follows Structure: A Media Sociology Manifesto. In Media Sociology, edited by Silvio Waisbord, 25-45. Cambridge: Polity.

Bilić, Paško. 2019. Media, Social Ontology and Intentionality. Javnost – The Public 26 (1): 1-16.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998a. On Television. New York: The New Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998b. Acts of Resistance: Against the Tyranny of the Market. New York: The New Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2005. The political field, the social science field, and the journalistic field. In Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field, edited by Rodney Benson and Eric Neveu, 29-47. Cambridge: Polity.

Crouch, Colin. 2004. Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

Couldry, Nick and Andreas Hepp. 2013. Conceptualizing Mediatization: Context, Traditions, Arguments. Communication Theory 23 (3): 191-202.

Curran, James. 2019. Triple crisis of journalism. Journalism 20 (1): 190-193.

Davies, Nick. 2008. Flat Earth News. London: Vintage Books.

Deacon, David and James Stanyer. 2014. Mediatization: Key Concept or Conceptual Bandwagon? Media, Culture & Society 36 (7): 1032-1044.

Della Porta, Donatella. 2004. Temelji politične znanosti [eng. Foundations of Political Science]. Ljubljana: Sophia.

Dinan, William and David Miller. 2007. Public Relations and the Subversion of Democracy. In Thinker, Faker, Spinner, Spy, edited by William Dinan and David Miller, 11-20. London: Pluto Press.

Franklin, Bob. 2003. “A good day to bury bad news?” Journalists, sources and the packaging of politics. In News, Public Relations and Power, edited by Simon Cottle, 45-61. London: Sage.

Franklin, Bob. 2011. Sources, Credibility and the Continuing Crisis of UK Journalism. In Journalists, Sources, and Credibility, edited by Bob Franklin and Matt Carlson, 90-106. New York: Routledge.

Gans, Herbert. 1979/2004. Deciding What’s News. Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Hardy, Jonathan. 2014. Critical Political Economy of the Media. London: Routledge.

Hepp, Andreas. 2012. Mediatization and the ‘Molding Force’ of the Media. Communications 37 (1): 1-28.

Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The Mediatization of Society: A Theory of the Media as Agents of Social and Cultural Change. Nordicom Review 29 (2): 105-134.

Hjarvard, Stig. 2013. The Mediatization of Culture and Society. New York: Routledge.

Krotz, Friedrich. 2017. Explaining the Mediatisation Approach. Javnost – The Public 24 (2): 103-118.

Landerer, Nino. 2013. Rethinking the Logics: A Conceptual Framework for the Mediatization of Politics. Communication Theory 23 (3): 239-258.

Lewis, Justin, Andrew Williams and Bob Franklin. 2008. A Compromised Fourth Estate. Journalism Studies 9 (1): 1-20.

Livingstone, Sonia and Peter Lunt. 2014. Mediatization: an emerging paradigm for media and communication studies. In Mediatization of Communication, edited by Knut Lundby, 703-724. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Lundby, Knut. 2009. Introduction: ‘Mediatization’ As Key. In Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences, edited by Knut Lundby, 1-18. New York: Peter Lang.

Lundby, Knut. 2014. Mediatization of Communication. In Mediatization of Communication, edited by Knut Lundby, 3-35. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Lundy, David. 2017. Lobby Planet Brussels. Brussels: Corporate Europe Observatory. Accessed 23 Mai 2024. www.corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/lp_brussels_report_v7-spreads-lo.pdf

Mair, Peter. 2013. Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. London: Verso.

Mazzoleni, Gianpietro. 2014. Mediatization and Political Populism. In Mediatization of Politics, edited by Jesper Strömbäck and Frank Esser, 42-56. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Mazzoleni, Gianpietro. 2017. Changes in Contemporary Communication Ecosystems Ask for a “New Look” at the Concept of Mediatisation. Javnost – The Public 24 (2): 136-145.

Mazzoleni, Gianpietro and Winfried Schulz. 1999. “Mediatization” of Politics: A Challenge for Democracy? Political Communication 16 (3): 247-261.

McNair, Brian. 2007. An Introduction to Political Communication. 4th ed. London: Routledge.

Murdock, Graham. 2017. Mediatisation and the Transformation of Capitalism. Javnost – The Public 24 (2): 119-135.

Pickard, Victor. 2019. The violence of the market. Journalism 20 (1): 154-158.

Prodnik, Jernej A. 2014. Protislovja komuniciranja [eng. Contradictions of Communication]. Ljubljana: Faculty of Social Sciences.

Prodnik, Jernej A. 2016. The instrumentalisation of politics and politicians-as-commodities. Annales: Series historia et sociologia 26 (1): 145-158.

Schlesinger, Philip. 1990. Rethinking the Sociology of Journalism: Source Strategies and the Limits of Media-Centrism. In Public Communication, edited by Marjorie Ferguson, 61-83. London: Sage.

Schlosberg, Justin. 2017. Media Ownership and Agenda Control. London: Routledge.

Schudson, Michael. 2011. The Sociology of News. 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton.

Schulz, Winfried. 2004. Reconstructing Mediatization as an Analytical Concept. European Journal of Communication 19 (1): 87-101.

Streeck, Wolfgang. 2014. Buying Time. London: Verso.

Strömbäck, Jesper. 2008. Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics. The International Journal of Press/Politics 13 (3): 228-246.

Strömbäck, Jesper and Frank Esser. 2009. Shaping Politics: Mediatization and Media Interventionism. In Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences, edited by Knut Lundby, 205-224. New York: Peter Lang.

Štětka, Václav. 2012. From Multinationals to Business Tycoons: Media Ownership and Journalistic Autonomy in Central and Eastern Europe. The International Journal of Press/Politics 17 (4): 433-456.

Thussu, Daya. 2008. News as Entertainment: The Rise of Global Infotainment. London: Sage.

Tomanić Trivundža, Ilija. 2014. Vernakularna vizualna politična kultura [eng. Vernacular visual political culture]. Javnost – The Public 21 (Supplement): 41-58.

Tumber, Howard. 2014. Back to the Future? The Sociology of News and Journalism. In Media Sociology, edited by Silvio Waisbord, 63-78. Cambridge: Polity.

Van Aelst, Peter, Gunnar Thesen, Stefaan Walgrave and Rens Vliegenthart. 2014. Mediatization and Political Agenda-Setting. In Mediatization of Politics, edited by Jesper Strömbäck and Frank Esser, 200-222. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Vobič, Igor. 2015. Osiromašenje novinarstva [eng. Impoverishment of Journalism]. Javnost – The Public 22 (Supplement): 28-40.

Vobič, Igor, Alem Maksuti and Tomaž Deželan. 2016. Who Leads the Twitter Tango? Digital Journalism 9 (5): 1134-1154.

Waisbord, Silvio. 2019. Communication: A Post-Discipline. Cambridge: Polity.

Williams, Raymond. 1978/2005. Culture and Materialism. London: Verso.

Zollman, Florian. 2017. Bringing Propaganda Back into News Media Studies. Critical Sociology 45 (3): 329-345.

About the Author

Jernej A. Prodnik

Jernej A. Prodnik is an assistant professor at the Department of Journalism, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and a researcher at the Social Communication Research Centre based at the same institution. He is currently a guest scholar at the Department of Media Studies (Media Systems and Media Organisation working and research group) at Paderborn University (Germany). He served as the head of the Department of Journalism between 2018 and 2021. Between 2014 and 2015, he was a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism at the Faculty of Social Sciences (PolCoRe research group), Charles University in Prague (Czechia). His principal research interests encompass the critique of political economy and historical transformations of capitalist societies with an emphasis on journalism, media and communication.