“In capitalism, the main purpose of technology is the effective organisation of capital accumulation in the form of the technical means of production” (Fuchs and Hofkirchner 2002, 161).

“We see how in this way the mode of production and the means of production are continually transformed, revolutionised, how the division of labour is necessarily followed by greater division of labour, the application of machinery by still greater application of machinery, work on a large scale by work on a still larger scale. That is the law which again and again throws bourgeois production out of its old course and which compels capital to intensify the productive forces of labour, because it has intensified them – the law which gives capital no rest and continually whispers in its ear: ‘Go on! Go on!’” (Marx 1849, 224).

“The advertisers’ strategy is to hammer it into people's heads as an unqualified desirability, indeed as a categorical imperative, that they must own the latest product on the market. In order for this strategy to be realised, however, producers have to constantly throw 'new' products onto the market (...). Built-in obsolescence increases the rate of wearing out, and frequent style changes increase the rate of discarding” (Baran and Sweezy 1966, 129,131).

1. Introduction

The development of media technologies as “new media”[1] is analysed in this article with the help of a Critical Political Economy theory approach[2], specifically on the basis of a Critique of the Political Economy of the Media (Knoche 1999, 2001, 2002). There is no problem in theoretically and empirically justifying the fruitfulness of a capital- and politics-centred Media Economics research approach, especially since in capitalism as the globally dominant economic and societal system, the fundamentally legitimised interaction of capital (companies) and politics (state) has a central system-stabilising and system-developing function.

A realistic examination of the laws of motion of (media) capital proves to be insightful for the analysis of the development of media technologies as “new media”, as it is precisely the development of technology – usually labelled with positive and euphorically connoted buzzwords such as “technical revolutions”, “technical progress” or “innovations” and “growth” – is regarded as constitutive (as a question of existence“) for the individual accumulation of capital and the necessary safeguarding and further development of capitalism into oligopoly or monopoly capitalism (Baran and Sweezy 1966). This circumstance applies increasingly in the context of the neoliberal paradigm in economic theory, policy and practice, which also legitimises a corresponding structural change in the media industry, which is driven forward by planned action on the basis of the greatest possible capital autonomy with the market as the almost exclusive regulator in the supposed “free play of forces” with planned state support (Knoche 1999, 149-151).

2. Theoretical Approaches to the Genesis, Diffusion, and Impacts of Technology

In criticism of the purely diffusion-theoretical approach dominant in economic neoclassicism, which does not do justice to a deeper social science explanatory claim due to its focus on technology and supply, which is considered unrealistic, Seeger (1996/97, 45-52) places technology genesis models at the centre of research into the technisation of audio-visual media. He differentiates between constructivist and social evolutionary approaches in a socio-economic research tradition with a strong institutionalist orientation. In what seems to me to be a justified differentiation from neoclassical, constructivist, and sociological approaches, he considers it more informative to analyse the decisions and strategies of political and economic actors in the introduction, application, and implementation of the more comprehensive media systems from a socio-political point of view, following a more political science-oriented approach by Mayntz et al. on large-scale technological systems and the significance of institutional contexts (Seeger 1996/97, 48).

Based on the theoretical approach of a Critique of the Political Economy of the Media, the development of media technologies as “new media” is considered from a number of points of view which, in my opinion, are of decisive importance for a realistic analysis, but which have nevertheless received little consideration in the Media and Communication Studies-literature to date. Under these “new” aspects of Media and Communication Studies, which are in reality relatively “old” but by no means outdated – taking into account the relevant economic, political science and sociological literature – the development of media technologies is analysed primarily taking into account the following fundamental aspects and contexts:

·

The accumulation of

capital by individual entrepreneurs as a “source of meaning” and “moving force”

for the necessary global (media) technology development;

·

Overall economic

development stages of global capitalism and “system optimisation” as decisive

strategy parameters;

·

There is the interaction

of the global economic and political strategies of the means of production

industry, the media industry, and the economy as a whole: media technologies as

a means of investment, production, distribution, and consumption;

·

There is the interaction

of strategies of planned qualitative/functional innovation (“technical progress”)

and psychological/aesthetic innovation as well as of planned

qualitative/functional obsolescence (“wear and tear”) and

psychological/aesthetic obsolescence (“obsolescence”) as entrepreneurial strategies

in the sales promotion of “new media” as well as the associated problem of “technical

and social regression”.

·

There is the antagonistic

process of strategies of convergence, universalisation, and diversification as

well as the concentration/globalisation of the worldwide media system driven by

this.

In general terms, the considerations centre on the interest in providing academic explanations as to why media technologies as “new media” are successively developed (note: media technologies do not develop, they are developed) in a planned[3] way that can be observed empirically without any problems. The aim is to contribute to a theory of media technology development[4] that takes into account the realisation that these media technologies are developed in the general process of the planned successive development of any technology in the capital accumulation interests of capital owners on their behalf in close planning cooperation with state institutions.

3. The Development of (Media) Technology in the Process of Capital Accumulation

In order to achieve

realistic academic knowledge and empirically supported theory development, an

analytical approach that understands capitalism

as a globally dominant economic and societal order as real and therefore takes its real

dominant core as the starting point for academic analyses seems to me to be

of comparatively great value for Media and Communication Studies. The

accumulation of capital and the production

methods and production (labour)

conditions necessary for its realisation as well as the necessary infinite production, sale, and

consumption of commodities[5]. As is well known, capital accumulation via profit maximisation is a very real “essential element” in

capitalism, and consequently also in the capitalist media industry, and a

frequently fundamentally legitimised, everyday economic and political

imperative for the owners of capital and dependent workers.

In developed capitalism, the type, development, and use of new (media) technologies are generally by no means determined by “random” inventions or by the desire to serve “technical progress” or the will to improve the fulfilment of human (communication) needs. The development of technology is therefore neither induced nor determined by technology (technology as “deus ex machina”) nor driven by demand or need (“consumer sovereignty”), as is often claimed. For a theory of media technology development that is not distracted by legitimising ideologies or media philosophies, but instead takes empirically proven or verifiable phenomena as the basis for theory formation, the starting point and benchmark are the defining “essential elements” of the capitalist economic and societal system, in particular[6]

·

the individual

accumulation of capital with its general susceptibility to crises;

·

state support for the

individual accumulation of capital;

·

the organisation of

production and labour (mode of production, productive forces and relations of

production);

·

the production, distribution,

and consumption of goods.

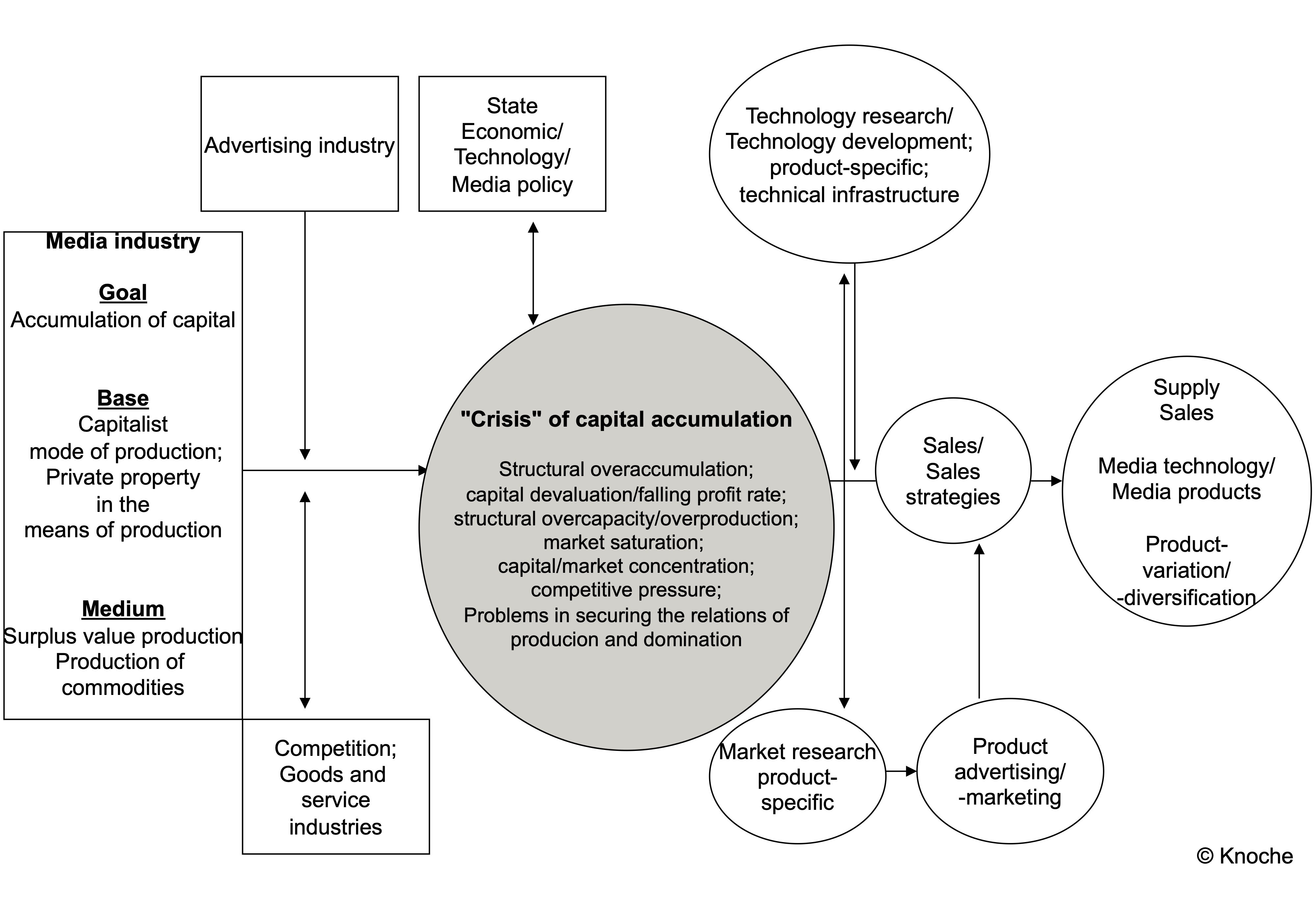

The “driving forces” influencing the development of media technology

are modelled in figure 1[7].

The dominant influencing factor is the activities of capital owners in the

private media industry to optimise individual capital accumulation based on the

capitalist mode of production by means of surplus value and commodity

production. The central parameter for the development of media technology is

the optimisation of the capital accumulation process, or more precisely: the

result of this process in the form of a return on the capital invested plus an “appropriate”

profit.

Figure 1: Factors influencing the development of media technologies as means of capital accumulation

Entrepreneurial action is primarily determined by either preventing,

overcoming, or “productively” utilising the consequences of a

large number of regularly “threatening” or real “crises”, which in

principle jeopardise profitable individual capital accumulation or (can) lead

to the devaluation or destruction of capital, in order to accelerate the

devaluation and/or destruction of competitors’ capital. Media companies operate

in competition with all other goods and service industries and under pressure

from the entire economy as an advertising industry. The development and use of

media technology is an important means of preventing and overcoming crises.

Media

technology development is driven forward by media companies in close “co-ordination”,

i.e., co-operation with the government’s economic, technology and media policies.

As the example of the introduction of private radio and television media in

Germany in the mid-1980s shows, economic policy and technology policy (the promotion

of nationwide cable and satellite technology) can be successfully pursued with

the help of or under the guise of well-co-ordinated media policy in the

interests of the industries benefiting from it. State technology policy as

economic policy also includes technology research and development subsidised

with taxpayers' money, especially in technical infrastructure (e.g.,

telecommunications), which was ultimately “supplied” to private capital as part

of neoliberal privatisation.

The

development of media technologies – which may be “valuable” in the eyes of

media users because they are (apparently) useful and satisfy their needs – is

literally worthless (not producing value) or capital-destroying for the

owners of capital if they are not sold at profitable prices in a way that

increases the capital value in the necessary quantity in the shortest possible period.

The profitable accumulation of capital is only successful if a “surplus”

(profit) is achieved through the massive sale and purchase of commodities. The

fundamental problem is that accumulation is not a one-off process of production

and sale, but that the goal of capital accumulation can only be achieved

through constant, almost infinite repetitions of this process. As this is a

cumulative process of the accumulation of constantly growing amounts of

capital, the non-value-enhancing idling of capital must be restricted or

prevented by accelerating and quantitatively expanding the process of

production and sale in order to secure the rate of

profit.[8]

From the

perspective of the individual accumulation of capital, it can be explained why

(product-specific) market research as well as advertising and marketing of

commodities, and sales and marketing strategies in general, are of central

importance in the current stage of oligopoly capitalism (Prokop 2000, 139-141)

for asserting the individual interests of capital owners in competition with

the individual interests of other capital owners in a society that is

fundamentally limited by human needs and necessities as well as by purchasing

power and the willingness to buy.

From the

perspective of the owners of capital, the development and use of changing[9] technologies are generally necessary in two ways in order to secure or expand the accumulation of capital. On

the one hand, the use of regularly changing technologies as a means

of production is necessary to change the mode of production

(mechanisation/automation as a means of strengthening the position vis-à-vis wage

earners, i.e., to “secure” the relations of production in the interests of the

owners of capital), to increase productivity and to reduce costs. On the other

hand, this process requires the use of regularly changing techniques as

a means of distribution and consumption. The incessant mass production

and sale of a multitude of different media technologies, each of which is

subject to constant change, is necessary because this is the only way to

achieve the desired accumulation of capital.

The use of changing media techniques as “new media” is indispensable for solving fundamental problems that regularly arise “anew” in the process of capital valorisation, especially for successful capital accumulators: The unprofitability of technical overcapacity and overproduction (measured in terms of sales volume) and the difficulty of avoiding overaccumulation (“unproductive” accumulation of capital) through profitable investment of surplus capital (that part of the “surplus”/profit that cannot be used profitably in previous production) (Kisker 2000, 70-71). An essential theoretical element for a realistic theory of the development of media technology is therefore the realisation that this development

·

in an inevitable[10] phased process

·

is necessarily driven

forward in the interests of capital owners.[11]

4. Media Technologies as Means of Investment, Production, Distribution, and Consumption

“The

conditions of the given capitalist mode of production and the inherent

inevitability of commodity production make them (the technologies, MK) at the

same time a moment of the valorisation of capital, [...] this also applies to

the process of discovering and developing the technologies themselves:

Technologies are developed and valorised as a means of producing and multiplying

capital” (Briefs 1983, 101).

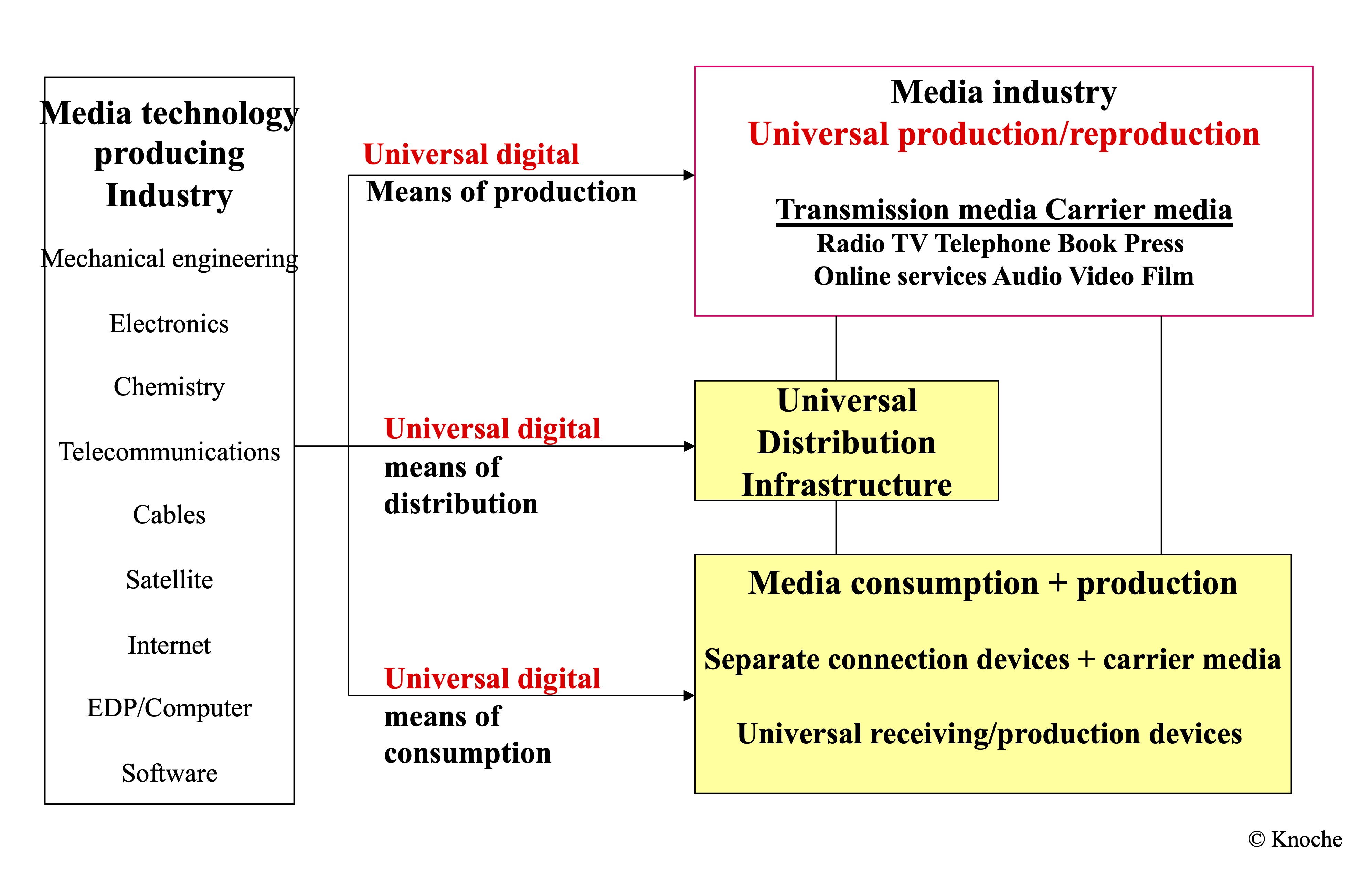

In Media and Communication Studies, the problem of “new” media

technologies as “new” media has so far been discussed primarily in terms of

journalistic aspects and, in the neoclassical economic tradition, from a market

perspective with a broad restriction to the consumer sector. For a more

comprehensive academic analysis and theorisation, however, it seems essential

to consider the development of media technology in the close context of the

production of the means of production, media production, media distribution,

and media consumption.[12]

Marx’s (1885, chapters 20 & 21) distinction between the two departments of social production, means of production for productive consumption and means of consumption for individual consumption, and their functions for the reproduction and circulation of total social capital is fundamental here. In this theoretical context, the different significance of the production and consumption of media technologies becomes recognisable concerning their functional transformations at the various stages of an interacting capital accumulation process: the commodity function of media technologies for the producers of means of production (sales tend to be to the entire producing economy), their consumption/use function as fixed capital (means of production), and finally the commodity function for the media producers and the consumption/use function for the consumers.

Figure 2: Media technology transformation as universal means of investment, production, distribution, and consumption

An essential starting point for the development of a “media technology

theory” from the perspective of a Critique of the Political Economy of the Media

as a theory of structure and action is – similar to Seeger (1996/97, 54-55)

– the general, partly media-specific interaction of a “linked technology chain”

(figure 2), in the case of television as a chain of “programme contribution”,

studio/production, broadcasting/transmission, reception/use and

recording/storage/playback technology. Altmeppen, Löffelholz, Pater, Scholl and Weischenberg

(1994, 46-47, 62-66) also emphasise – for innovations and investments in

newspaper companies – the economic conditionality and the process character of

innovations as well as the far-reaching restriction to innovations that act as

triggers for “chains of effects of innovative measures” (product, process,

structural and contract innovations).

It is

precisely the combination of the use of “new technology” as a means of

production, distribution, and consumption that promotes the “consumerist circle”

(Candeias 2001, 169-174), which is advantageous for

the owners of capital, in that the reproduction of labour power in leisure

time, in addition to its “valorisation” in production time, also becomes

beneficial for profit maximisation through mass

(technological) consumption. In the perspective of a Critique of the Political Economy

of the Media, the “capitalist production process is viewed as a unity of the

labour and valorisation process” (Mendner 1975,

19-36). Consequently, the causes, types, and consequences of the development of

media technologies as “new media” are also analysed to a large extent from the

point of view of the development of the productive forces as well as the

associated working methods and conditions as a connection between the mode of

production and the ways of life.

In

general, the relationship between the production of means of production and

media production and distribution (figure 2) is fundamentally different from

that between media production and media consumption: On the one hand, there are

mutual competitive and complementary relationships between strong individual

economic capital accumulation interests within and between highly concentrated

industries, in particular mechanical engineering, electronics, chemicals,

telecommunications, cable, satellite, computers, and the Internet. (Kubicek 1984, Kubicek and Rolf

1985, Luyken 1985, Michalski 1997). Various media

technologies are developed in combination with financial and media policy

support from the state (Tonnemacher 2003a, 215-246).

On the other hand, the owners of capital in the media industry (production and

distribution) decide on the use of investment and production resources under

monopoly or competitive conditions according to microeconomic criteria. In this

context, the innovation and obsolescence strategies of the manufacturers of

means of production also play a role that should not be underestimated,

particularly since the media technology manufacturing industry generally

produces means of production as well as means of distribution and consumption

(hardware and software). The (entertainment) electronics industry not only

produces technology but also programmes (music, video). Basically, the

producers of means of production have to deal with “sophisticated

buyers whose concern is to increase their profits. [...] producers

of producer goods make more profits by helping others to make more profits”[13] (Baran and Sweezy 1966, 70, 71).

The

capital accumulation interests of individual media producers result in a

compulsion to regularly replace means of production and the associated changes

to production processes due to the constant need to reduce costs. In principle,

the aim is to delay new investments in means of production until the technical

equipment used has been amortised, in the narrower sense until it has been

written off in terms of value (for tax purposes) (Baran 1966, 152-158). As an

increase in production in previous areas of production tends to jeopardise

profit maximisation interests due to the widespread saturation of needs and

wants, surplus capital, which is a defining feature of capitalist development

as what Baran and Sweezy (1966, chapter 3) term “the

tendency of surplus to rise” (Baran and Sweezy 1966,

58-113), is transferred to rationalisation investments on the one hand and

invested in new areas of production based on “new” technologies on the other.

As the example of the development and use of “new technologies” in the press sector in particular shows, a change in technology as a means of investment and production is of eminent economic importance for the owners of capital in the first instance. Only secondarily is a subsequent change of technology as a means of distribution and consumption of significance. This also becomes clear in the chronological sequence of the development and use of changing technologies in the press sector. Since the mid-1970s, “journalism in the computer society” (Weischenberg 1982) has been driven by the interests of capital owners in “technical rationalisation” and increased productivity through the “computerisation” of newspaper production as a change in the mode of production and the relations of production. Although the economically necessary combination of media technology as a means of production with corresponding means of distribution and consumption (“online newspapers”) has long been sought in the press sector due to the enormous potential for reducing production (printing, paper) and distribution costs (Neuberger 2003, 65-66; Tonnemacher 2003b), such a combination will only be fully realised if it can contribute to the successful accumulation of capital. Concerning traditional press products, the technical pressure to innovate in the consumer sector is comparatively low, as press products are more or less short-lived consumer goods and the use of (printed) press products is not associated with technical receivers.

5. Innovation, Obsolescence, and Commodity Aesthetics

“The buyers experience the aesthetic

innovation as an inevitable, although fascinating, fate. […] Aesthetic

innovation, as the functionary for regenerating demand, is thus transformed

into a moment of direct anthropological power and influence, in that it continually

changes humankind as a species in their sensual organization, in their real

orientation and material lifestyle, as much as in the perception, satisfaction

and structure of their needs” (Haug 1986, 42, 44).

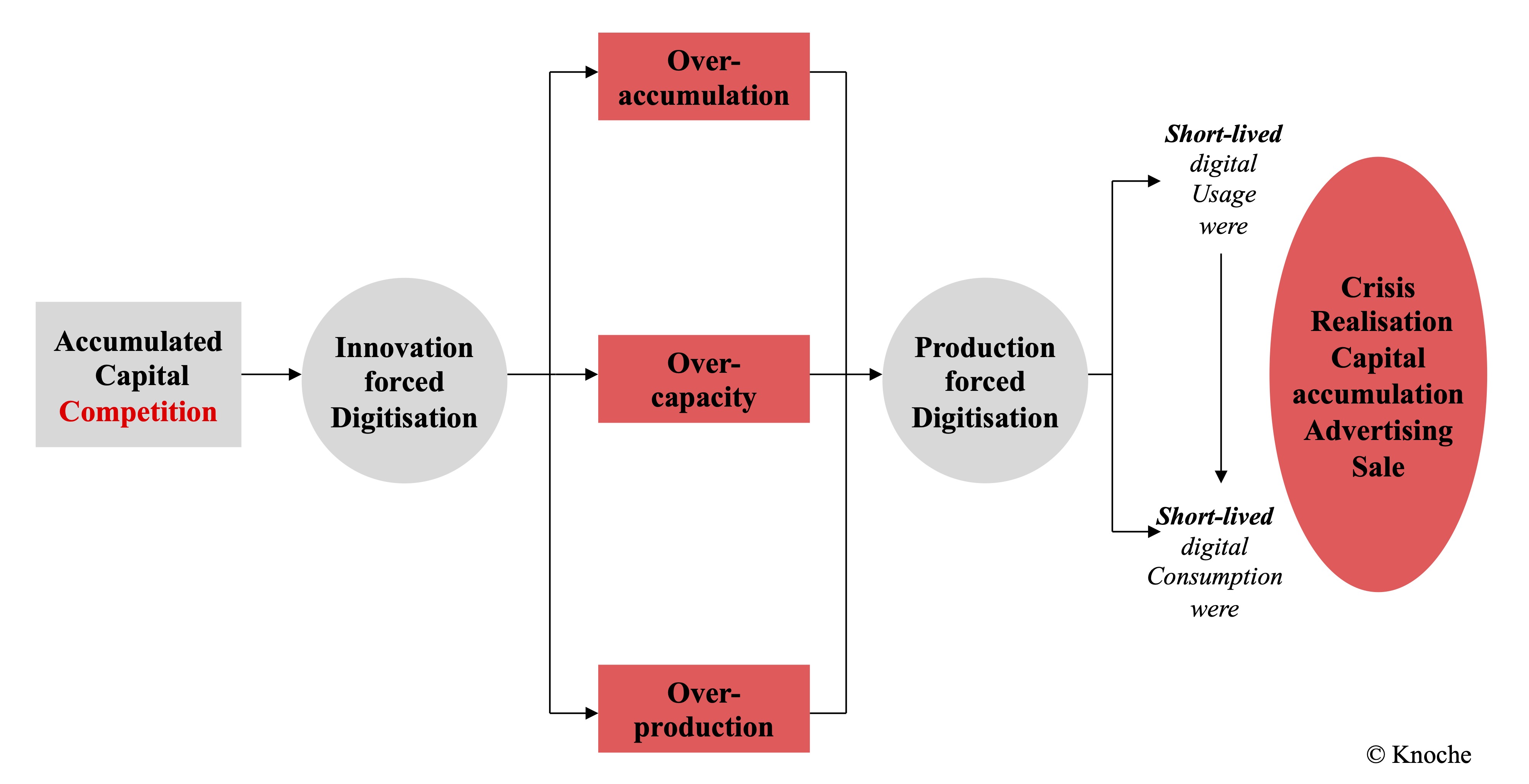

With the help of global neoliberal privatisation and deregulation policies, nation-states, in co-operation with alliances of states such as the European Union, have in recent decades created very large-scale opportunities for capital owners from various industries and sectors to accumulate capital with “new media”[14]. These state privatisation measures were very urgent for capital owners at the time, as there were general capital valorisation problems worldwide due to a lack of investment opportunities for “surplus” capital and, above all, due to “saturated” markets.[15] Consequently, there were areas of application for a change in media technologies in connection with the development of new spheres of capital investment and new mass markets in “new” media sectors such as “cable television”, AV media, digital radio, digital television (pay TV), telecommunications, online services, multimedia, and the Internet, as well as the development of new market segments in traditional media sectors with largely saturated markets using product variations and product diversification.

Figure 3: Chain reactions of investments and product-“innovations” in the capital accumulation process

Figure 3: Chain reactions of investments and product-“innovations” in the capital accumulation process

Due to the connection between media technologies as a means of investment, production, distribution, and consumption, investment/production and product innovation constraints necessarily arise, which regularly trigger certain “chain reactions” of investment and product “innovation” in the capital accumulation process (figure 3). The driving forces here are the capital already accumulated to a high degree through decades of extremely successful profit maximisation (high degree of capital concentration), the devaluation of which is threatened by over-accumulation, overcapacity, and overproduction, combined with the danger of “saturated” (sub-)markets. In this context, the (further) development and use of old and new media technologies, i.e., production, compression/storage, transmission, encryption, and reception technologies in the past[16], present, and future, play a central role. With their help, it is possible to achieve strategic goals that are fundamental to capital valorisation in the sense of profit maximisation (Knoche 1999, 158-161). The main strategy applied, the replacement of “old” with “new” media technology, serves three main “transformation” objectives:

· Durable consumer goods are transformed into short-lived consumer goods[17].

· Durable consumer goods are transformed into consumer goods with the shortest possible shelf life.

· The expansion of the production and sale of short-lived consumer goods (“disposable camera”, retail sale of information, pay-per-view, automatic deletion of music tracks “retrieved” from the Internet after a short time, etc.).

Three basic innovation/obsolescence[18] strategies (Bodenstein 1977, 10-13; Haug 1980, 136-142, 159-170) are used to achieve these goals, which are essential for the long-term accumulation of capital (figure 4):

·

Planned functional-technical obsolescence as a real functional change/extension[19]

with regard to the basic and/or additional use-value of a product;

·

planned qualitative obsolescence as a real deterioration in use-value

(“built-in” premature wear and tear, shortening of the physical/economic

service life of products, also by omitting possible quality and durability

improvements through “pigeonholing” of available knowledge and patents);

·

planned psychological/aesthetic obsolescence as “aesthetic”

innovation/obsolescence as a conscious devaluation of use-value (“unfashioning”

of a long-lasting product that is still in use or basically usable).

Figure 4: Strategies of the means of production and consumption’s innovation and obsolescence

As a rule, these three strategies “of shortening the lifespan of products and of accelerated fashion change” are applied in combination as “capitalist laws” (Bodenstein and Leuer 1976, 204-205), whereby the interaction of innovation/obsolescence strategies of the two Marxian “departments of social production” of means of production and consumption mentioned above is also fundamental here (Glombowski 1976, 37-40, 316-340). Especially in the media sector, these combined strategies of planned functional-technical, qualitative, and psychological/aesthetic obsolescence are often realised in the form of system variations. In product systems consisting of several product elements (e.g., camera, film, projector, accessories), a central element is changed in such a way that the entire previous system becomes unusable or appears to be unusable. This strategy is known to be used in the computer sector at extremely short intervals (hardware/software/additional device combinations).

On the one hand, the planned obsolescence in the form of the

deliberately produced material “short life” (“becoming unusable” due to physical

wear and tear) of the “old” media technologies that are still in use or no

longer in use, but are still fundamentally usable, successfully

stimulates replacement or additional purchases (replacement, second and

additional devices) to a considerable extent. However, only the offer of a “new”

technology that is no longer compatible with the “old” technology, ideally

accompanied by the complete cessation of production of the “old” technology, actually makes the “old” technology “obsolete” because it is

unusable. This process creates the necessary pressure on the supposedly “sovereign”

consumers to open up new mass markets for replacement

or additional purchases. Criticising the neoclassical and neoliberal dogma of “consumer

sovereignty”, Joan Robinson, for example, concludes that “the claim that the

system of private enterprise is geared towards satisfying consumer desires is

pointless. Rather, consumers are the meadow on which entrepreneurs graze. We

have become accustomed to a system that functions for the benefit of the

producers and in which the benefit to the consumer is merely incidental”

(Robinson 1966, 69).

On the other hand, a predominantly “psychic” obsolescence is

constantly being generated in the form of “aesthetic innovations”, which act as

an “aesthetic obsolescence” within the framework of an all-encompassing “commodity

aesthetic” characteristic of capitalism, through a wide range of technical

product variations (design, equipment, reception quality, retrofitting,

functional and valorisation modifications, combination with additional devices,

etc.) (Haug 1986). This type of aesthetic innovation “becomes

the dominant force in monopoly capitalism” (Bodenstein

1977, 38) and causes consumers to subjectively lose the previously

(good) concrete use-value of media technologies, even though they are still

usable in a technical sense. It is not only concrete product-related

advertising and marketing measures that contribute to the success of such

strategies, but also a diverse, all-encompassing stimulation (via advertising,

marketing, PR, journalism, art, culture, education, upbringing) of a general

social re-evaluation process of values in the consciousness of consumers

(disdain for the “old”, appreciation of the “new”, orientation towards “fashion”,

reduction of inhibitions towards “throwing away”, overcoming thriftiness, etc.)

(Bodenstein and Leuer 1976, 227).

Similar to radio and television programmes, press products, especially daily newspapers, tend to have the advantage of being short-lived consumer goods which, as a means of communication similar to food and luxury foods, enable calculable daily, weekly etc. mass sales as “replacement purchases” – additionally secured by the form of a fixed subscription – which in turn is the prerequisite for the actually profitable advertising business. It is no coincidence that the press industry was traditionally one of the industries with the highest rates of profit.

The long-term success of the coupled

strategies of innovation and obsolescence is essential for the successful

accumulation of capital. In order to arrive at an

academic explanation of the existential necessity of the interplay of

the most diverse forms of these strategies, in particular their dominant “psychic/aesthetic”

variants, it is expedient to “analyse new phenomena in the context of a

transformation of the mode of production” (Haug

2003, 27). In doing so, it first becomes recognisable how necessary the

development and application of profitable information, communication and media technologies, in particular the

integration of electronic data processing (computers) and the Internet, is for

a mode of production that ensures the accumulation of capital. A new mode of

production based on modified means and processes of production serves to

increase labour productivity and change labour relations (the power relationship

between capital owners and wage earners in favour of the capital owners).

However, this transformed mode of production and the associated increase in the

amount of capital employed is only advantageous if the increase in product

quantities through the profitable sale of these products leads to the

realisation of capital accumulation (return flow of the capital employed plus profitability).

The higher the use of new technology increases labour productivity and the amount of capital employed, the greater the pressure on individual companies to increase product quantities and to use innovation and obsolescence strategies in order to sell their “own” products profitably in the face of market saturation and limits on demand and purchasing power (Bodenstein 1977, 32-41). But even a successful accumulation of capital creates a new production constraint insofar as “surplus” capital must be invested in new (technical) products in order to ensure the continued profitable valorisation of capital. This contradictory nature of the change in the mode of production through the use of new technologies and the associated reinforcement of the general production constraint also explains the central importance of the development of media technologies as “new media” and, in connection with this, the use of primarily “psychic/aesthetic” innovation and obsolescence strategies, which are essential for the realisation of “profitable”[20] capital accumulation. The successful application of these strategies, which simultaneously anchor capitalist commodity production in individuals’ consciousness as “advantageous” in macroeconomic and social terms, actually leads to large-scale and planned destruction of use-values (Bodenstein 1977, 39) and to “secondary exploitation” (Haug 1986, 103) in the area of consumption in addition to primary exploitation in the area of production.

The causes and types of innovation and obsolescence strategies are shown in figures 3 and 4. The general causes for the necessity of using such strategies are the goal of capital accumulation and the pressure to valorise accumulated capital. The specific causes are the consequences of the renewal of the mode of production through the use of new production processes and new means of production: the increase in labour productivity through technical rationalisation, the change in labour relations, and the increase in the quantity of capital. This process requires an increase and variation in product quantities, the profitable sale of which, necessary for the realisation of capital accumulation, can only be achieved through the interrelated use of various innovation and obsolescence strategies.

Technological change is generally in the interests of both hardware manufacturers (players and carrier/storage media) and content/programme producers. For the programme industry, there is a need to valorise content anew via new carrier media in old or new markets. Such valorisation is an economic necessity for them because, on the one hand, there is a lack of successfully exploitable new programmes and, on the other hand, successful products (“hits”) can only be sold repeatedly via new carrier media (Knoche 1999, 158-159).

6. The Media System’s Antagonistic Process of Convergence, Universalisation, and Diversification

The extent, sequence, and speed of the convergence and diversification processes are mainly determined by the strategies of financially strong (media) groups in highly concentrated media markets. Economically, they have the necessary capital and market power and politically they can assume favourable framework conditions and a high degree of assertiveness based on radical privatisation and deregulation policies. Consequently, the strategic role played by convergence, universalisation, and diversification in the global capital valorisation process of these companies must be examined. Above all, this means analysing which degree of convergence is more conducive or enforceable for which companies in which media sectors in the respective phases of different competitive and market strategies and which is not.

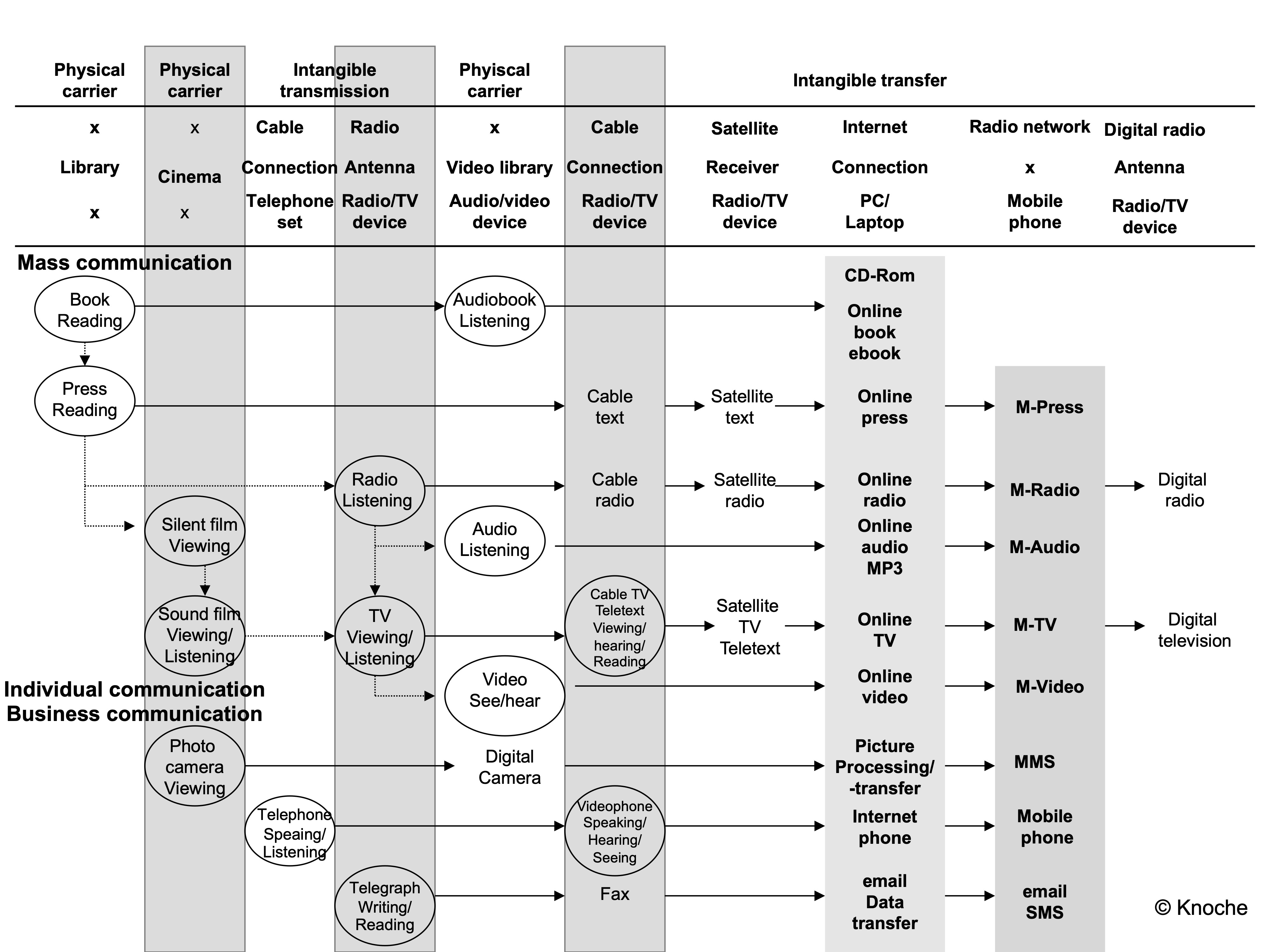

Figure 5: Media technology’s development, diversification, convergence, and universalisation

Figure 5 is an attempt to depict the development, diversification, convergence, and universalisation of media technologies as comprehensively as possible, particularly concerning the phases of this development based on key characteristics, divided into mass communication media and individual and business communication media. Vertically (from top to bottom) – also as an indication of phases over time – the complementary developments of “new media” are arranged as a diversification process according to the criterion of their physicality, but also according to which human senses are “newly” addressed in which combination in the course of development. The further developments within the individual media (sectors) are arranged horizontally (from left to right) according to the scale of material carriers or immaterial transmission.

The process of technical change in the media and the associated (partial) convergence/universalisation process should be shown in its basic features. In principle, four strategies for the planned successive change of media technologies can be recognised empirically based on the development to date[21]:

·

additional media types,

differentiated according to forms of communication (in the area of mass

communication: book, press, film, radio, television, audio, video);

·

per media type, a

development of generations through a change of physical carriers and/or

transmission channels, e.g. cable, satellite, online,

M-TV or record, CD, DVD (not shown in figure 5 for reasons of clarity);

·

a diversification of models

per media type and generation (not shown in figure 5 for reasons of clarity);

·

per media type,

generation, and model, partial convergence/universalisation across

different reception devices and transmission channels

(television/cable/satellite, computer/Internet, mobile phone/mobile

communications).

The process of convergence/universalisation (Knoche 1999, 165-172) has become possible in particular based on the cross-media digitisation of production and transmission and is being driven forward based on cable, Internet, and mobile phone technology. For example, the future of audio-visual media technology (production, distribution, consumption) is determined by the convergence and diversification strategies of well-funded companies in the interested industries, primarily the film/video/television and music industries (production and distribution), the electronics, chemical and computer industries (hardware), and the telecommunications industry (distribution). A distinction must be drawn between the technical, economic, institutional-organisational, content-related, and functional convergence of traditionally separate individual, business and mass communication.

The traditional diversification into

different media sectors – primarily differentiated according to technical

development stages – according to the communication forms of text/image

communication (press, book), sound communication (radio, sound carrier), moving

image/sound communication (television, video, film) as well as voice and data

communication (telephone/computer) is just as important as the diversification

into different transmission channels (terrestrial, cable, satellite, telephone

network, Internet) and finally the diversification into a large number of

different carriers, film) and voice and data communication

(telephone/computer), as well as the diversification into different

transmission channels (terrestrial, cable, satellite, telephone network,

Internet). The diversification into a large number of

different carrier media and reception devices has been economically necessary

and will continue to be used in the foreseeable future to a large extent in the

interests of capital valorisation. Complementary to this, separate, “internal”

convergence processes are being driven forward for each of the traditional and “new”

media, including television, which is used as a means of diversified multiple valorisations

of media products and media technologies in the global capital valorisation

process.