Abstract: Critical political economy of the media investigates how changes in the array of forces that exercise control of media institutions liberate or limit the public sphere. South Africa’s political economy of transition from apartheid to democracy was notably characterised by the emergence of new black capitalist interests merging with established white capital to refashion multi-racial capital, facilitated by a Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) strategy that aimed to address the racial injustices of the past. These changes greatly impacted media ownership, diversifying a previously racially homogenised and localised apartheid media market. The ‘new’ South Africa also moved from racial capitalism to neoliberalism as its economic system. This study investigates whether these ownership diversity changes in the South African print media market in the first twenty years of its democracy (1994–2014) liberated or limited the public sphere. A total of 684 newspaper front-page and editorial articles were analysed using both quantitative and qualitative content analysis, to aggregate as well as investigate deeper meanings and associations in diversity trends. South Africa’s neoliberal economic context substantially informs the nature of print media content transformation and diversity, which is found to be elite driven, marking the emergence of class continuities. This despite a specialised BEE affirmative action programme envisaged to cultivate transformed and diverse media content through transformed ownership. The study concludes that attempts to transform, diversify, de-westernise, and decolonise the media systems in post-colonial countries will be futile if the power of neoliberalism to perpetuate class inequalities and the race dynamics of the past remain underestimated and unaddressed.

Keywords: Critical Political Economy of the Media, neoliberal capitalism, Global South, South Africa, print media, media transformation, media diversity, class inequalities, race

Acknowledgement: This article is based on a conference paper accepted at the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR) 2021 conference, Political Economy (PE) Section. I would like to thank the Chair of the PE section, Professor Rodrigo Gómez García, for his valuable input into this article. I would also like to thank my mentor Professor Sarah Chiumbu for her ongoing crucial support, guidance, and input into my work.

1. Introduction

Critical political economy of the media (CPEM) investigates how changes in the array of forces exercising control of media institutions liberate or limit the public sphere (Golding and Murdock 2000). South Africa’s political economy of transition from apartheid’s white minority rule to democracy with black majority rule through the African National Congress (ANC) was notably characterised by the politically inspired unbundling of white corporations, facilitated by a Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) strategy, which saw the emergence of new black capitalist interests merge with established white capital to refashion multi-racial capital (Barnett 1999). These deals greatly affected the media, especially the print media, which underwent major changes in ownership and control that diversified the market with the entrance of black and international ownership. In this transitional period, the media was also impacted by the ‘new’ South Africa shifting its economic system from racial capitalism to neoliberalism. Cedric Robinson (1983) coined the term “racial capitalism” in his seminal work, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, where he conceptualises racialism as central to the capitalist expansion of society: “The development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, so too did social ideology. As a material force […] racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism” (Robinson 1983/2000, 2). Robinson developed this term to correct the developmentalism and racism that led Marx and Engels to mistakenly believe that European bourgeois society would rationalise social relations (Melamed 2015). The South African apartheid context significantly contributed to this origination of the concept of “racial capitalism”. Robin Kelley (2017) notes that Robinson was initially introduced to the idea of “racial capitalism” in the 1970s by exiled South Africans engaged in vigorous debates about the nature of the apartheid system and intellectuals who used this phrase to refer to South Africa’s economy under apartheid (cited in Al-Bulushi 2020).

Overall, the South African media underwent key changes in contexts that according to the critical political economy of the media (CPEM) approach would frame its media content, namely in its political context, economic context, and ownership diversity. The CPEM approach links media content to the structure of the state, economy, and economic foundation of a news organisation which includes ownership (Schudson 2002). The BEE strategy aims to address the ills and injustices of apartheid policies of systemic racial discrimination that unfairly disadvantaged the ‘non-white’ racial groupings, i.e., the black majority, Indians, and Coloureds, of equal rights and opportunities such as participation in the economy, ownership of capital, and work, to name a few. The country has since enshrined the BEE strategy in a policy called the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) Act No. 53 of 2003, which aims to mainly facilitate an increase of black ownership and economic transformation in corporates of different sizes (Govenden and Chiumbu 2020). As a member of the corporate sector the media is also subject to this B-BBEE Act, and it is the media’s sole transformation standard.

In the South African context, media transformation has come to be conceptualised as media diversity in terms of both ownership and content (Nelson Mandela 1992, cited in Lloyd 2013; Boloka and Krabill 2000; Steenveld 2012; Right to Know Campaign 2015). In this regard, Boloka and Krabill (2000, 76) capture a widely accepted conceptualisation of successful media transformation as reflecting the diversities of South African society in both ownership and content:

For the record, then, we define the successful transformation of South African media as being achieved when it reflects, in its ownership, staffing, and product, the society within which it operates, not only in terms of race, but also socio-economic status, gender, religion, sexual orientation, region, language, etc. This is only possible if access is opened – again in ownership, staffing, and product – not only to the emerging black elite, but also to grassroots communities of all colours.

South Africa’s media transformation approach engages with a key focus of critical political economy of the media (CPEM), the relationship between ownership and content. CPEM contends that structural components including ownership have traceable consequences for media content diversity (Golding and Murdock 2000). The study adopts a CPEM perspective for analysing the ownership and diversity of content and discourses of the press in South Africa with regards to its media transformation agenda, which expects that diversity of racial ownership i.e., BEE ownership will lead to content transformation on these levels. This study investigates these premises of the CPEM approach within a post-colonial context, that of South Africa, to answer the question: did racial diversity changes in the South African print media market in the first twenty years of its democracy (1994–2014) liberate the public sphere (Golding and Murdock 2000)?

2. The Political Economy of Transition: From Apartheid’s Racial Capitalism to Neoliberal Democracy

Print media transformation in South Africa is a product of the political economy of transition that took place at the ushering in of democracy in 1994. The country underwent a negotiated transition from an apartheid system of white minority rule to a Constitutional democracy of black majority rule, which began in 1990 when F.W. de Klerk declared the unbanning of the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan African Congress (PAC), as well as other organisations, and committed his National Party (NP) government to “negotiating a fully inclusive, non-racial, and democratic constitution” (Southall 1994, 630). A settlement was eventually reached, and the first democratic elections took place in 1994 and were decisively won by the ANC. The new democracy was negotiated with compromises on both sides: the ANC conceded that a Government of National Unity (GNU) would rule for five years with Nelson Mandela as president and F.W. de Klerk as deputy President (Orkin 1995). According to Hadland (2007), South Africa was set on a new path of political and economic development. Notably, sanctions were eased and the country became open to foreign investment (Hadland 2007). The political change from apartheid to democracy was formally enshrined in the non-racial South African Constitution, established as the supreme law of the land, which effected many political, socio-economic, human rights, legal, linguistic, media, and geographic changes, to name but a few. In the transitional period, the broad ‘transformation’ agenda in South Africa was adopted after elections as an inherently racial strategy to rectify the economic injustices of apartheid, and within this context ‘media transformation’ emerged. The appearance of black-owned companies marked the start of ‘transformation’ through the BEE agenda. The re-structuring of print media ownership was particularly noteworthy through the entry of international capital and domestic black empowerment groups (Barnett 1999). As democracy progressed, the change to racial ownership diversity in the print media continued through more BEE ownership deals.

The country also moved from an economic system of racial capitalism to neoliberalism. The latter has been on the rise since 1994, leading to a wide perception that government has overemphasised macroeconomic stabilisation at the expense of poverty reduction (Tomaselli and Teer-Tomaselli 2008). Apartheid’s economic system of racial capitalism operated on the biased accumulation of wealth based on the super-exploitation of black people by white people through capital–labour relations. The black majority suffered the most because they were placed at the bottom of an apartheid-crafted racial hierarchy that deemed the ‘white race’ superior and the ‘black race’ inferior. Class became racialised in South Africa; the elite class were made up of the white population, and the lower classes and poor consisted mainly of the black majority.

The media mirrored the politics, economics, and institutionalised racism of the day. During apartheid the media was mainly owned by white-only mining big business; this however, was operated as state-run media, key to the success of apartheid and forming the central conduit of its propaganda and white supremacist racist ideologies. The print media is described by Hadland (2007,11) as

largely undisturbed a language-and race-based oligopolistic division of the spoils between two major Afrikaans newspaper companies, Nasionale Pers and Perskor, and two English ones, Times Media Limited (previously South African Associated Newspapers) and the Argus Publishing and Printing Company.

Since the ushering in of democracy the country has adopted a mixed media system – a combination of libertarian and social responsibility. The social responsibility component mainly emerges from the media in the ‘new’ South Africa being vested with an important democratic and public interest role, as a tool for unification and democratisation (Barnett 1999). In this regard, the media’s role and policies is informed by the South African Constitution, which enshrines human rights such as equality, human dignity, labour rights, healthcare, food, water, social security, and children’s rights (Section 7). The Constitution also enshrines freedom of expression, including media freedom (Section 16), a central principle of the libertarian model. The libertarian aspect also emanates from South Africa’s history of British colonialism, as well as post-apartheid media policies. For example, the South African Press Code takes its preamble from the South African Constitution and also draws from the International Federation of Journalists (IFA), which is grounded in normative liberal theories of the news media, such as freedom from statutory regulation (Rodny-Gumede 2014). At the same time, this Press Code identifies that the print media has a social responsibility to citizens: “The media’s work is guided at all times by the public interest, understood to describe information of legitimate interest or importance to citizens” (Preamble, The Press Code of Ethics and Conduct for South African Print and Online Media 2019). The Press Code also enshrines Constitutional principles in reporting, such as the best interests of the child and human dignity, and condemns gender discrimination. The post-apartheid media also operates within the neoliberal economic system adopted by the country when establishing democracy. Notably, the print media is located in the corporate sector and therefore market. Currently, the print media market consists of the Big 4 – Independent Media; Media 24 (whose parent company is Naspers or Nasionale Pers); Caxton; and Tiso Blackstar Group (previously Times Media Limited). The South African media market is an oligopoly, dominated by a handful of corporations. Assessments of the South African print media market indicate a high level of market concentration. By the C4 measure of concentration, the sector has remained consistently concentrated (since 1997) at a relatively high level. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and Noam measures also indicate high concentration (Angelopulo and Potgieter 2013).

3. Political Economy of Content Diversity in South Africa

This study adopts a critical political economy of the media (CPEM) perspective for analysing the ownership and diversity of content and discourses of the press in South Africa with regards to its media transformation agenda. It theoretically engages with CPEM’s belief that the media’s external context frames its content. This approach relates the content, which is the outcome of the news processes, to the “structure of the state and economy and to the economic foundation of the news organization” (Schudson 2002, 251). Here, ownership is regarded as one economic element of a media organisation and is a major area of focus. CPEM is “interested in the interplay between economic organization and political, social and cultural life” (Golding and Murdock 2000, 73). CPEM research thus attempts to understand the relationship between the media’s power and state power, as well as the media’s relationship to economic sectors (Wasko 2004). CPEM’s grounding in Marxism means that it foregrounds various lines of critique regarding capitalism and the media, such as market concentration (Wasko 2004); commodification (Mosco 2009); the cultural and political implications of concentrated media ownership (Downing 2011); a corporate focus of in-depth accounts of ownership patterns like mergers, acquisitions, monopolisation, and internationalisation (Olorunnisola et al. 2010); the power of ownership on editorial work and decisions (McNair 1998); and capitalist mass media resulting in a decline of diversity (Garnham 2011). Of particular relevance to this study is CPEM’s focus on the relationship between ownership and the diversity of discourses (Golding and Murdock 2000; McChesney 2004; Wasko 2004; Garnham 2011). CPEM theorists recognise the profound impact of media ownership patterns on the diverse range of discourses in content (Golding and Murdock 2000). It also identifies capitalism and concentrated ownership patterns as detrimental to diverse citizen-oriented content. One of CPEM’s beliefs is that capitalist corporate control contributes to a dominant ideology of capitalist-friendly content and a reduction in information diversity (Garnham 2011). It has also been argued that growing corporate control and hyper-commercialism impacts content through, for example, consumerism and class inequality. Civic values and anti-market activities are marginalised, and the best journalism is pitched to the needs and prejudices of the elite, with only a few exceptions (McChesney 2004).

This study explores the effect on content diversity of South Africa’s political economy of transition that took place in the early 1990s which significantly altered the context of the media, namely: transitioning from a political system of apartheid to democracy; moving from an economic system of racial capitalism to neoliberal capitalism; and the advent of corporate South Africa’s multi-racial capital formations facilitated by the BEE strategy that racially diversified and internationalised media ownership, signalling the start of media transformation. CPEM is premised on the critical importance of the media in relation to the moral good and articulates fundamental requirements for an ideal communication system as open, diverse, and accessible, using this to measure the performance of existing systems (Golding and Murdock 2000). In line with this ideal, this approach investigates how changes in the array of forces that exercise control of media institutions liberate or limit the public sphere (Golding and Murdock 2000). The study draws from this ideal and critically considers the question: did these diversity ownership changes liberate or limit the public sphere? This study understands “liberating the public sphere” (Golding and Murdock 2000) in the context of South Africa’s print media as diverse ownership cultivating diverse content as envisaged by the country’s media transformation approach. A liberated public sphere in this instance specifically means the transformation of the racially unjust apartheid-era print media with ‘diverse content’ that cultivates an equal public sphere representative of all South Africans. This also speaks to the widely accepted view of successful media transformation in South Africa as representing the diversity of South African society, as captured by Boloka and Krabill (2000). It should be noted that the concept of ‘public’ in ‘public sphere’ has also evolved and no longer refers to one single public. Fourie (2011) notes that society is now characterised by a new kind of public that is not a coherent population with shared values; rather, it is marked by hybridisation, fragmentation, the rise of minorities and minority rights (2011). A single Habermasian public sphere no longer exists; instead, several public spheres claim legitimacy (Fourie 2011). Drawing from Fourie’s (2011) perspective, it is expected that the post-apartheid print media ‘public sphere’ be representative of multiple and diverse publics and not a homogenised public as was the case during apartheid, where only the ‘white race’ was represented and catered for in the media’s ‘public sphere’.

4. Methodology

In

the

South African context, transformation equals media diversity, and in

order to

decipher whether BEE ownership has led to content transformation on

these

levels, as expected by the country’s transformation agenda thus

liberating the

public sphere (Golding and Murdock 2000),

the

extent of content diversity was determined through a content analysis

method

applied to coverage in the first twenty years of democracy (1994–2014).

The key

measures of content diversity in extant studies are topics and sources (Carpenter 2010; Masini et al. 2017; Humprecht and Esser

2018),

which are applied to this study. Seven categories of topics were used

for all

articles. Six of the topics are focused on the South Africa context

only: specifically,

news about South African Party politics; Government; Socio-economic

rights;

Labour; Business; and Human interest/celebrity/arts/entertainment. There

is

also an “Other” category for foreign news along with news that does not

fall

within the first six topics. For each front cover story, the prominent

voice or

source is also recorded according to nine categories: “Government”,

“Business”,

“Political party”, “NGO”, “Civil society”, “Trade union”, “Expert in the

field”

(for example, academic, author, researcher). There is also a “Multiple”

and an

“Other” category. The “Multiple” category is for stories that used

multiple

sources in a balanced manner where no source dominated the story. The

tone of

each article was also categorised as “positive”; “negative”; or

“neutral”.

Radebe (2017) posits that tone is an

indication of

societal power dynamics, which is particularly relevant to this study

that

deciphers the transformation in coverage of which race and power is

central because

of past injustices.

The methodology of the study consisted of both quantitative and qualitative content analysis, to aggregate as well as investigate deeper meanings and associations in coverage (Krippendorf 1989; Davies and Mosdell 2006), specifically the diversity trends of the 684 articles analysed selected through a “purposive sampling” technique (Benoit 2014, 272). A total of six newspapers were selected: Business Day, Sowetan, Sunday Times, The Star, Sunday Independent, and Mail and Guardian. The post-apartheid print media sector consists of the historically English and Afrikaans press. In the first twenty years of democracy the print media sector as a whole has undergone notable racial diversification of black ownership. The newspapers in the sample belong to the historically English print media companies – Independent Media, Tiso Blackstar Group, and M&G Media. The historically Afrikaans print media companies, Media 24 and Caxton (previously Perskors), are not included in this study. The unit of analysis are the leading front cover story as well as editorial page (editorial voice and main-ed column), because these are regarded as the most prominent and powerful framing sections of a newspaper. The front-page leading story features the issues that newspapers regard as most important (Radebe 2017), and the editorial page may frame reader’s views (Van Dijk 1995). The breakdown of the total of 684 articles are 228 front cover stories, 228 editorial voice pieces, and 228 main op-ed articles.

5. Neoliberalism Perpetuates Elite Class Dominance through the Media: Findings

The transformation trends of the sample of articles (N = 684) analysed reflected little diversity and rather significant class inequalities, as well as a commercial logic, all of which are manifestations of the country’s neoliberal economic context. The power and privilege of the elite class is significantly visible in the sample of articles. Coverage significantly favoured elite-driven topics, prominent voices, and economics news, while the working and lower classes were neglected in the overall coverage. This is unsurprising, since the media can perpetuate the power of the elite class by maintaining their dominance; as Davis (2003, 670) posits,

mass communication is central to notions of power. Whether the mass media are a means of upholding or undermining the democratic process, a means of maintaining class dominance or ensuring the continued circulation of powerful elites and dominant culture, elite–mass communications is key.

In the case of South Africa, its neoliberal economic context substantially informs the nature of print media content transformation and diversity, which was found to be elite-driven in six specific areas. The commercialisation of content was also evident in the sameness of coverage in topics and prominent voices across the sample of six newspapers. The overall neoliberal agenda in the print media is also amplified by government and the print media displaying a joint anti-labour sentiment in the coverage of protests which marked a deviation from the dominant negative coverage of government. The neoliberal trends found in the coverage are categorised across six dimensions, summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Neoliberal coverage trends across six dimensions (N = 684)

5.1. Elite-Driven Topics and Prominent Voices

The topic that garnered the highest coverage in all the samples of articles was news about the political elite at 38% (N = 684), comprising Government (22%) and Party politics (16%). This was followed by Socioeconomic rights (30%); Other (21%); Labour (4%); and Business (3%). This weighting points to a lack of diversity and, broadly, transformation in the topics of coverage. Typically, the political elite topics dominated the front cover pages and editorial pages, hampering content diversity, and the nature of this coverage showed that it was largely not citizenry-driven. For each front cover story the prominent voice is recorded (N = 228). The breakdown of prominent voices on the front page were: Multiple (31%); Government (18%); Political party (13%); Citizen (13%); Other (12%); Business (8%); Academic/expert in the field (3%); Trade union (2%); NGO (1%); while Civil society was absent (0%). Findings show that a significant 39% of prominent voices were elite driven – Government (18%); Political parties (13%); and Business (8%), whilst alternative and counter-hegemonic voices were sparse at 13% (Citizen 12%; NGO 1%); and no civil society voices were recorded. Trade unions are representatives of the working class and garnered just 2% of prominent voices. A case in point regarding the dominance of elite sources is seen in the Sunday Independent newspaper sample of articles in 2012 and 2014. In 2012 all prominent voices of the six front cover stories were “political parties”, and in 2014 all stories used politically related and business sources. This finding is indicative of a larger trend of elitism found in the prominent voices in the overall sample of front cover articles.

These findings concur with Radebe’s (2017) study on the representation of the nationalisation of mines debate by the South African English corporate press in 2011, which found that capitalist elite sources define the nationalisation discourse. Therefore, there is clear dominance in South Africa’s newspapers of the elite class as a prominent voice eroding other important voices; for example, “academic/expert in the field” voices in the present study constituted 3%. The reliance on elite government voices by the print media also limits overall content diversity and perpetuates the power of the elites (Brown et al. 1987).

The dominance of elite discourses in the South African press found here is a reproduction of neoliberal ideologies. Chiumbu (2016) argues that neoliberalism has caused the South African print media to operate fully according to a commercial logic that favours elite discourses and privileges capitalism whilst marginalising alternative and counter-hegemonic voices (cited in Radebe 2017).

5.2. Elite Economic News is Favoured

The study regarded economics news for “ordinary citizens” as coverage about the effects of the economic base for the poor and working class and generally citizen-framed coverage of economic issues. Contrastingly, “elite” economic news is coverage primarily crafted for the economically privileged, such as primarily serving investors and the wealthy through a focus on figures and shares. About 31% (N = 14) of the front cover socio-economic articles on the front page concerned economics news. Significantly, 13 out of these 14 articles can be regarded as “elite economics news”, and 12 of these articles were published in the Business Day newspaper. Only one article was categorised as “economic news for the ordinary citizen”; this was published in the Sunday Independent newspaper.

Overall, findings indicate that economics news gets prominent attention on the front cover of the “elite” and business-focused Business Day, which is a newspaper targeted at the upper and educated classes. This leaves a sizeable gap in economics news for the “ordinary” citizen. These findings can be explained by capitalism’s market ideology. Jacobs (2004) argues that due to the market ideology that drives corporate media in South Africa, economics and business news is “mainly limited to figures with little emphasis on the political and ideological nature of these figures” (cited in Radebe 2017, 63). Jacobs further notes that therefore the connection between the economics news published and its relation to inequality and poverty is avoided (cited in Radebe 2017).

5.3. Under-Representation and Negative Depiction of the Working Class

The

study

of media content diversity also encompasses missing and underrepresented

issues

in media content. Humprecht and Esser

(2018, 2) posit that “A lack of

diversity is

usually established by identifying types of news content that are

missing from

or underrepresented in a particular news outlet”. Working-class struggle in post-apartheid South Africa has been a major

issue of contention that is indicative of the persistence of the

severe

marginalisation of black people after the end of apartheid, and it has

also

impacted economic growth. The apartheid

system’s brutal racial

exclusion

denied the black majority the benefits of industrial protection and

welfare

provisions, which were reserved for white workers (Paret 2017).

During apartheid, black workers were

systemically denied access to residential neighbourhoods and valuable

public

facilities, including security, that were available to other segments

of the

working class (News24 2014). The working

class in

South Africa, which is still mostly black, faces the significant

apartheid

continuity of poverty and poor living conditions, and this often

culminates in

the use of protests as a tool to be heard; for instance, there are

ongoing

strikes in the mining sector.

Generally, there are frequent work stoppages because of

strike action, limiting economic growth (Forbes

2018). Hence,

protests are the major foci of

resistance in the working class’s fight for decent wages,

healthcare, education for their children, and humane living and

working

conditions. A case in point: in 2012 the infamous Marikana massacre

took place

at the Lonmin Platinum mine in Marikana, North-West Province, after a

weeklong

wildcat strike by miners for a wage increase and to address poor

living and

working conditions for miners and their families. The strike

culminated in the

killing of 34 mineworkers by the South African Police Force (SAPS)

using lethal

force (South African History Online

2012). It

has been found that the living conditions of the Marikana workers are

unbearable, and families are on a knife edge in that any slight

increase in the

price of food and basic goods pushes them to yet deeper levels of

poverty (News24 2014).

Despite the historical and economic importance of this issue for post-apartheid South Africa, the study found that coverage on labour issues of protests and workers’ rights were under-represented, making up only 4% of topics (N = 684). In the same coverage, the tone of the labour grouping is significantly negative (34%), whilst no stories depicted labour positively, and 41% of stories showed neutral tones which, upon closer analysis, were missed opportunities to critically voice labour injustices. A typical example of labour being portrayed negatively is seen in a Sunday Independent newspaper front cover article (9 January 2000) with the headline “Our policies have failed us”; most of the article comprises direct quotes from an interview with the then Finance Minister Trevor Manuel. The article states that the Minister was particularly “scathing of COSATU [Congress of South African Trade Unions] for its attempts to launch job creation marches against government”. The reporting is unbalanced and unfair to COSATU, as it critiques and provides a negative portrayal, yet fails to present COSATU’s voice and perspective. Overall, this front cover story reads like an opinion piece written by a government representative under the guise of providing an objective news piece. Another typical case in point of labour’s negative representation is a Business Day newspaper editorial voice (5 January 2009) with the headline “Reality check”; this reports on South Africa’s local economy and COSATU’s proposals to amend labour laws. Overall, this article favours the business perspective whilst displaying bias against the labour position. The tones exhibited in labour coverage conveys the message that working-class issues are not important to the media’s agenda, reflecting South Africa’s societal class power dynamics (Radebe 2017) that began during apartheid.

5.4. Under-Representation and Simplistic Coverage of Issues Affecting the Poor

Socio-economic rights globally refer to the protection and the basic needs of the poor. South Africa faces a severe socio-economic crisis comprising abject poverty, high unemployment, and growing inequality, largely faced by the black majority (Terreblanche 2012). It could be expected, then, that socio-economics news should report on the plight of the poor. However, findings show that coverage was under-represented, simplistic, and sensational in nature. Only one story was dedicated to poverty and inequality in the front-page leading stories (N = 228), yet this story was sensationalised, which attests to the profit-making motives of the print media. Humprecht and Esser (2018, 4) posit that news diversity is hampered by profit motives: “[…] reporting that relies on personalization, simplification, and polarization seem to attract larger audiences and thus more advertisers than in depth and perspective-rich reporting does”.

The coverage on “poor” and “rural” people consisted of these groupings being made visible mostly in embarking on social protests. The sparse coverage of “rural” South African people and the socio-economic issues they face are a direct consequence of the rise of neoliberalism and its incumbent commercial imperatives in South African newsrooms. The State of the Newsroom Report SA (2013) found that when cost-cutting and rising distribution costs occur, print companies constantly review distribution costs and uneconomical routes are reduced. Rural towns are the first to be poorly serviced and become less important, leading to a news focus on urban areas. Hence, neoliberalism and its associated commercial imperatives have essentially privileged the most ‘economics-based’ audiences in coverage. Similarly, 18% of front-page socio-economic stories centred around the sensational areas of drama, crime and disaster, which aims at attracting audiences (Humprecht and Esser 2018) through a human-interest angle, illustrating the underlying commercial imperatives of the press.

The socio-economic crisis in South Africa is widely attributed to the neoliberal policies adopted by the ANC government. Alexander (2010) asserts that many socio-economic problems are attributed to post-apartheid neoliberal policies that, for example, caused inadequate investment in public goods and underfunding in key areas, especially housing. Mottiar and Bond (2011, 11) concur with this position, arguing that “The ANC government’s neoliberal economic policies have amplified poverty and inequality”. Yet 27% of socio-economic front-page coverage was about simplistic updates on government actions and policies as they related to socio-economic issues, with no critical reporting about the government’s role in the socio-economic crisis. For example, coverage amounted to fact-based updates on government actions and policies regarding issues such as housing, schooling, drugs at schools, education, and pharmaceutical policies. The press has dismally failed to hold government accountable for its major role in the socio-economic crisis facing South Africa, particularly in adopting neoliberal policies that favoured economic growth at the expense of key service delivery areas.

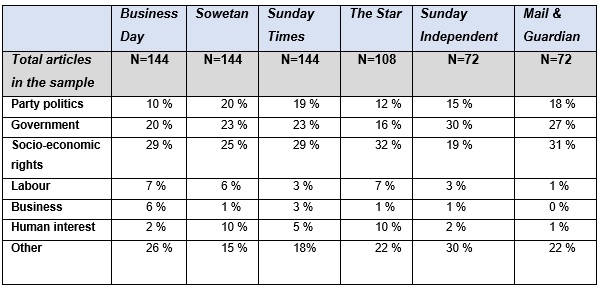

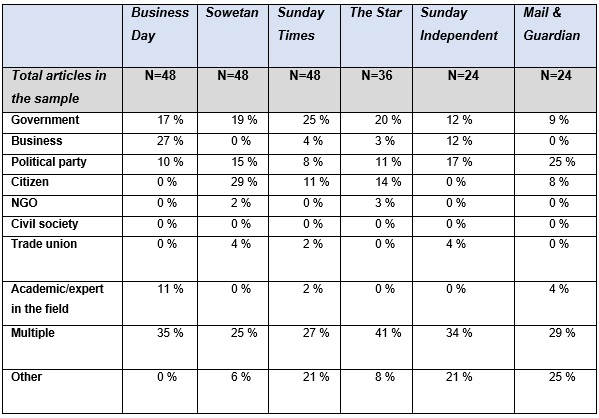

5.5. Sameness of Content in Topics and Prominent Voices Across Newspapers

The study found trends of sameness of content in topics and prominent voices across the six newspapers in the sample. This is indicative of a lack of overall diversity in the issues reported and the voices heard in the South African print media, as reflected in Tables 2 and 3:

Table 2:

Topic breakdown per newspapers of all articles (N = 684)

Table 3: Prominent voices of front cover

articles (N=228))

Carpenter (2010, 1065) notes that consolidation has led to sameness of content: “The consolidation of traditional news media outlets has been said to have led to a similarity in the presentation of content across media outlets […] newspapers typically narrow their coverage to retain readers when faced with a threat of competition”. The significant global growth of consolidation, also known as concentration in media ownership, can be traced to the neoliberal turn in economics and society, which gave rise to the elimination of media restrictions (Warf 2007). Hence, the sameness of content trends found in this study can be attributed to the global rise of neoliberalism and its entrance into the South African print media market in 1994. Sameness of content is also indicative of the commercial logic of the print media in South Africa. The striking commercialisation of the media in democratic-era South Africa can be attributed to this neoliberal ideology. Hadland (2007, 16) notes that “one of the most striking trends in the post-1994 period has been the commercialisation of the South African print media sector”.

5.6.

Government as a Promoter of the

Neoliberal Agenda

In the shift to neoliberalism, the state has transformed from a provider of public welfare to a promoter of markets and competition (Birch 2016). In the coverage of labour protests there is a rare consensus between government and the print media – both display an anti-labour narrative. Therefore, government works as a promoter of market interests and capitalism. The dominant trend in government press coverage is high negative tones towards government: 46% negative vs. 3% positive. In its coverage of labour protests, the press follows a “protest paradigm” that favours the official government position. Lee (2014) defines the “protest paradigm” as “a pattern of news coverage that expresses disapproval toward protests and dissent” (cited in Leopold and Bell 2017, 721). The second characteristic of the “protest paradigm” is reliance on official sources and official definitions (McLeod 2007, cited in Leopold and Bell 2017). When journalists allow those in power to define protests, the result is that protestors are characterised by their deviance from societal norms rather than by their struggle for a cause (Leopold and Bell 2017, 721). One trend in the sample of articles was the good government and bad labour binary, where issues involving labour versus government predominantly saw the print media privilege the government position. Protestors were also demonised as social deviants for embarking on strike action and represented as unruly and unmannerly. For example, a front cover article (6 February 2001), “Mbeki takes aim at public sector unions” in the Sunday Independent newspaper, reports on the ongoing public sector strike and favours the government perspective. The first three paragraphs privilege government’s voice and views about the public service strike, mostly regarding their discontent with organised labour. Both the views of then-President Thabo Mbeki and the Minister of Public Service and Administration, Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi (who is directly quoted), are presented in the first half of the article as prominent voices. The demands of the trade unions as well as their planned strike action are mentioned, albeit secondarily to the perspective of the government. The third paragraph states: “While the government is anxious to avoid a showdown with the union movement, it is also determined not to allow unions to derail its macro-economic policy or its plans to free funds used for wages to increase spending on infrastructure”. The discourse of the article frames labour’s protest action as a threat to economic growth and the infrastructure development of the country.

Thus, the government position was only portrayed favourably in issues regarded as a threat to capitalism. Organised labour power has long been a threat to capitalism (Chiumbu 2016). In this rare exception, the print media joins government to advance capitalism, in effect protecting the ruling neoliberal ideology. This indicates the presence of a neoliberal agenda in the press.

6. Class and Race Power Dynamics Perpetuated by Neoliberalism: Analysis

The findings show that print media coverage largely perpetuates the dominance of the elite (Davis 2003), highlighting the power of neoliberalism in the media. As Mylonas (2015, 252) posits, “even quality journalism is succumbed to the logics and rationales of neoliberalism” (cited in Avraamidou 2020, 481). Elite perspectives are favoured in topics, prominent voices, and economics news coverage, while the issues the working class and poor uniquely face in South Africa are severely underrepresented and depicted negatively, sensationally, and simplistically. In post-apartheid South Africa, terms like ‘the elite’, ‘privileged’, ‘working class’, and ‘the poor’ are racialised as legacies of colonialism, as well as apartheid’s economic system of racial capitalism. Black South Africans were denied economic opportunities during colonialism and thereafter apartheid from the late 1940s (Time 2020). Hence, during apartheid privilege was white and poverty black, due to racially biased capital and economic gain. Presently, South Africa has a population of 58.78 million; black people make up the majority at 80.7%, whilst 8.8 % are Coloured, 7.9% are white, and 2.6% are Indian/Asian (Stats SA 2019). Despite being the minority, Anwar (2017) notes that white people in South Africa still hold the lion’s share of all forms of capital and control a large chunk of the economy. Anwar (2017) defines “all forms of capital” as Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) market shares, land, home ownership, and human capital in the form of knowledge, skills, and education. The black majority comprise most of the poor, the working class, the unemployed, and grant recipients, and make up the least of the elites and capital owners. A South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) 2017/2018 report found that 64% of black, 41% of Coloured, 6% of Indian and 1% of white South Africans are living in poverty (SAHRC 2018). Official unemployment is at 27%, and this is significantly higher among black youth (Forbes 2018). Cilliers and Aucoin (2016) note that the majority of the white population in South Africa continues to maintain considerable economic privilege, while black people comprise the majority of the unemployed and of social grant recipients. Since class remains racialised in South Africa, these findings represent significant apartheid continuities of the black majority and the issues they face of being underrepresented and misrepresented in coverage. Kitis et al. (2018, 150) notes that “During apartheid, media discourses contributed to naturalizing racial segregation and White supremacy”. Similarly, Hadland (2007) contends that general news and socio-economic news pertaining to the black majority were omitted from mainstream print media narratives.

Therefore, the diversity changes in ownership through an increase in BEE ownership have failed to facilitate diverse and transformed coverage for the black majority that cultivates an equal public sphere for all South Africans. A critical political economy of the media (CPEM) approach of these findings surmises that changes in ownership and control of the print media did not liberate the public sphere. The apartheid-era public sphere that misrepresented and excluded the black majority in coverage has not been liberated (Golding and Murdock 2000).

According to the CPEM approach, there are certain contextual factors that frame the media (Golding and Murdock 2000; Wasko 2004; Schudson 2002). The findings of this study emphasise the paramount power of the economic context as the leading frame for media content in the South African print media, trumping other factors such as a specialised transformation policy, a change in diversity of ownership, and a change in political context that saw the black majority take power through the ANC political party. These findings fundamentally point to print media content significantly displaying a neoliberal identity that parallels the CPEM perspective that the economic context of the media is critical in informing its own role (Golding and Murdock 2000).

The neoliberal-driven content found by this study is not surprising, since neoliberalism has been amplified since democracy in 1994 and has impacted various aspects of the media. For example, it has cultivated a consistently high level of print media ownership concentration from the apartheid period onward. Duncan (2016) notes that the concentration of print media ownership seen in the apartheid era continued in the first twenty years of democracy. The consistently high ownership concentration in the South African post-apartheid market by the C4, HHI, and Noam measures discussed earlier parallels global trends of the effect of neoliberalism on the media industry. Warf (2007) argues that the significant global growth of the concentration in media ownership can be traced to the neoliberal turn in economics and society that gave rise to the elimination of media restrictions. McChesney (2001) captures the impact of neoliberalism on the media industry and contends, the level of concentration in the media industry is so stunning as has only been seen in a few other industries. Critical political economy posits that excessive media concentration and commercialism impacts content through, for example, consumerism and class inequality, and as a result the best journalism is pitched to the elite’s needs and prejudices (McChesney 2004). South Africa’s print media coverage reflects this dispensation of CPEM. It is found that content is fundamentally pitched to the elite and marginalises the issues and representation of the working class and poor, indicating a class inequality contrary to the remit of South Africa’s ideal for media transformation as it relates to diversity (Boloka and Krabill 2000).

A contemporary study by Fuchs and Mosco (2012, 129) argues that Marxist theory is of “enormous” importance for critical communications studies today, and in critically examining communication it is of great importance to “engage with the analysis and critique of capitalism”. In Marxist terms, the print media in South Africa continues to be stratified along the structures of class inequality (Fuchs and Mosco 2012). The press shifted from being a white minority elite-driven press in the apartheid epoch to a neo-elite-driven press which consists of the black elite and yet also still consists of mostly white privilege, despite a politically driven transformation policy that racially diversified ownership.

CPEM also flags the dangers of media concentration for media diversity. For example, Garnham (2011) contends that concentration results in a loss of diversity. Similarly, Wasko (2004) articulates that media concentration ought to be considered for possible influences on content, such as availability, quality and tabloidisation of news, and the homogenisation of content. The South African print media case study illustrates the loss of content diversity as an effect of media concentration built by neoliberalism. Therefore, the power of neoliberalism and its commercial imperatives is currently overriding the democratic and transformation role of the print media in South Africa as a purveyor of diverse topics, voices, and narratives.

7. Conclusion

The print media in South Africa is essentially located within a neoliberal and capitalist economic system where the profits and the market rule; therefore, it is unsurprising that the findings have shown that the fair coverage of the poor, unemployed, and working class are not prioritised, because these are considered the most uneconomical consumers. The findings of the study are in line with assumptions of critical political economy of the media (CPEM) that capitalist ownership has led to bourgeois ideology in the press (McChesney 2004), seen in the elite-driven nature of content. The racially diverse changes in ownership facilitated by BEE did not significantly liberate the public sphere (Golding and Murdock 2000). This study has indicated a potential explanation: black ownership strategies have been based on capitalist and neoliberal strategies, which emphasise the power of neoliberalism.

The findings of the study also bring to the fore

considerations

for CPEM theory and especially its application to post-colonial

contexts. According

to CPEM, the diversity of ownership patterns should have traceable

consequences

for the diverse range of discourses in content (Golding

and

Murdock 2000), which is also the assumption of the country’s

transformation agenda that black ownership would lead to diverse and

transformed content. However, in the case of South Africa’s print media,

diversity of ownership through BEE has not had significant traceable

consequences for the diverse range of discourses. Whilst the general

analysis

of capitalism that CPEM advances is valid in South Africa, this approach

does

not take the specificities of individual countries into account,

particularly

in relation to post-colonial societies such as South Africa, where the

interaction of racism and capitalism in the media is important to

consider. For

example, the theoretical causal link between ownership diversity and

content diversity

articulated by CPEM (Golding and Murdock

2000)

does not capture the media diversity nuances of race and ownership,

which is

critical for a country like South Africa where racism was

institutionalised and

framed the development of the media. CPEM defines ownership in terms of

Western

media scenarios as public and private only, and with a study focus on

individual owners such as media moguls, as well as ownership patterns,

i.e.

media concentration, oligopoly, and monopoly. Within this context, I

pose the

question that de-westernisation scholars have been attempting to answer:

is

Western theory suitable as a theoretical lens in the study of media in

post-colonial contexts? In the last two decades calls to de-westernise

Media Studies

have emerged from scholars based in the West. Chiumbu

and Radebe (2020, 2) note that movements by

these

scholars aim to “internationalise”, “de-westernise” or “decolonise” this

field.

Scholars fundamentally argue that theories of communications are

unsuited to the

conditions of the African continent (see Nordenstreng 1997; Berger

2002;

Banda 2008; Obonyo

2011; Chiumbu

and

Radebe 2020). In these de-westernisation discourses, scholars

argue that

theories of communication are difficult to apply to Africa because they

have

been developed within the context of liberal pluralism or a CPEM

approach (see Banda 2008; Obonyo

2011; Chiumbu

and

Radebe 2020). The findings of this study also bear consequences

for

attempts at diversifying, de-westernising, and decolonising media

systems in

post-colonial countries. These collective efforts will be futile if the

power

of neoliberalism to perpetuate past class and race continuities remains

overlooked,

underestimated, and unaddressed. The shift to neo-liberalisation in 1994

meant

that the economy became subject to a newfound de-racialised system that

was seen

as democratically progressive in comparison to the discrimination of

racial capitalism;

however, this amplified capitalism in the South African media. Knoche

(2021, 331) notes that

“the capitalisation of the media industry is hardly a suitable means to

solve

macroeconomic and societal problems, for example in the sense of

distributive

justice for society as a whole. On the contrary: it promotes the further

capitalisation and commercialisation of the entire social and societal

life

with negative consequences”. Drawing from this, the further

capitalisation of

the media had negative consequences for media transformation and

diversity

imperatives, as shown by this study. In the case of South Africa’s print

media,

more capitalism has resulted in hampering the country’s attempts at

distributive justice through the transformation project of Black

Economic Empowerment.

References

Al-Bulushi, Yousuf. 2020. Thinking racial capitalism and black radicalism from Africa: An intellectual geography of Cedric Robinson’s world-system. Geoforum. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Thinking-racial-capitalism-and-black-radicalism-An-Al-Bulushi/d7168479aea2b1ff558a5680fb3efca9b3cb7b0d

Alexander, Peter. 2010. Rebellion of the poor: South Africa's service delivery protests – a preliminary analysis. Review of African political economy 37 (123): 25-40. Accessed 10 March, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03056241003637870?casa_token=gFPQltS1O2gAAAAA%3AvmVsAocfn2BTAFCfPR3duvzhScmUG_vIfA-oAr77NcBmerWikjf2jgHWAZxVT4HE3TFZcK9moxel6g

Angelopulo, George and Petrus Potgieter. 2013. The economic specification of media ownership in South Africa. Communicatio 39 (1): 1-19. Accessed January 30, 2022. https://nca.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02500167.2013.740057#.YhTel4pBw2w

Anwar, Mohammad. 2017. White people in South Africa still hold the lion’s share of all forms of capital. Accessed September 30, 2018. https://theconversation.com/white-people-in-south-africa-still-hold-the-lions-share-of-allforms-of-capital-75510

Avraamidou, Maria. 2020. The “Refugee Crisis” as a Eurocentric Media Construct: An Exploratory Analysis of Pro-Migrant Media Representations in the Guardian and the New York Times. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 18 (1): 478-493. Accessed October 16, 2021. https://triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/1080

Banda,

Fackson.

2008.

African political thought as an epistemic framework for

understanding African

media. Ecquid Novi 29

(1): 79-99. Accessed

March 2, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02560054.2008.9653376?casa_token=eiI8iEPZ4e4AAAAA:wtJmgH9WvLKZdy1nKuBPaR4rdbE4-eqCrfZuysU_NcUTyoiaEphwLWNqKXsyrhui-TA0HwV4eZxKPg

Barnett,

Clive.

1999. The limits of media democratization in South Africa: politics,

privatization and regulation. Media, Culture & Society 21

(5):

649-671. Accessed April 2, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/016344399021005004?casa_token=_SjZeKWxPaYAAAAA:vuL-IeR_1xHaxfAo8JPYaNe1mO6wcYyUZfr4PxuPDFZtDR-iK8Mtx9PUbTzfgVVpak8DVUK3w-uApg

Benoit, William. 2014. Content analysis in political communication. In Sourcebook for Political Communication Research, edited by Erik P. Bucy & Lance Holbert, 290-302. London: Routledge.

Berger,

Guy.

2002. Theorizing the media: Democracy relationship in Southern

Africa. Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 64 (1):

21-45. Accessed

March 15, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/17480485020640010201?casa_token=wjfZixc3mlEAAAAA:q-hlAnb6ugXfLDtFfRdCeI1n2Kg0Lv4Sqse610ZAA2DXtA2bTxQEqfOQV9nKavEvNEdt1KkgNMSi0w

Birch,

Kean.

2016. How to think like a neoliberal: Can every decision and choice

really

be conceived as a market decision? Accessed June 19, 2018. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/01/29/how-to-think-like-a-neoliberal/

Boloka,

Gibson Mashilo and Ron Krabill.

2000. Calling the Glass Half Full: a response to Berger’s Towards an

analysis

of the South African media and transformation,

1994-1999. TRANSFORMATION-DURBAN: 75-89. Accessed February 10,

2018. http://transformationjournal.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/43.-Krabill-Ron.pdf

BROAD-BASED

BLACK

ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT ACT NO. 53 OF 2003. Government Gazette 38126.

Accessed

March 3, 2018. https://www.wylie.co.za/wp-content/uploads/BROAD-BASED-BLACK-ECONOMIC-EMPOWERMENT-ACT-NO.-53-OF-2003.pdf

Brown,

Jane

Delano, Carl R. Bybee, Stanley T. Wearden

and

Dulcie Murdock Straughan. 1987.

Invisible power:

Newspaper news sources and the limits of diversity. Journalism

Quarterly 64 (1): 45-54. Accessed March 10, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/107769908706400106?journalCode=jmqb

Carpenter,

Serena.

2010. A study of content diversity in online citizen journalism and

online newspaper articles. New Media & Society 12

(7):

1064-1084. Accessed January 10, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444809348772?casa_token=ne-YR3ucV34AAAAA:RnkUWbiZDEK4S377mnNMwsqnmvUb8m4ml2W_Fd1Q213rVwMr3JtI_pJ-DSMOt58e2U09MFkOjN2UnA

Chiumbu,

Sarah. 2016. Media, race and capital: A decolonial analysis of

representation

of miners’ strikes in South Africa. African Studies 75

(3):

417-435. Accessed April 3, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00020184.2016.1193377?casa_token=uZaLqdPeYHEAAAAA%3A9GzL_V8F0vwtlOJKLfthECTkVBi5jII25hhTmRidqJvvrk1JtvlTVaAJg1IPVOtKZnQjgWpdzsC0gA

Chiumbu,

Sarah H. and Mandla Radebe. 2020. Towards a decolonial critical

political

economy of the media: some initial thoughts. Communicatio:

South African Journal of Communication Theory and Research 46

(1):

1-20. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.1080/02500167.2020.1757931

Cilliers,

Jakkie and Ciara Aucoin. 2016.

Economics, governance

and instability in South Africa. Institute for Security

Studies Papers no.

293: 1-24. Accessed March 15, 2018. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC197029

Daniels,

Glenda.

2013. State of the newsroom South Africa 2013: Disruptions and

transitions. Wits Journalism. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://journalism.co.za/new/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/State_of_the_newroom_2013.pdf

Davies, Máire

Messenger, and Nick Mosdell. 2006.

Practical

research methods for media and cultural studies: Making people

count. Athens,

GA: University of Georgia Press.

Davis,

Aeron.

2003. Whither mass media and power? Evidence for a critical elite

theory

alternative. Media, Culture & Society 25 (5):

669-690.

Accessed June 10, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/01634437030255006?casa_token=2nZcNgRqIm0AAAAA:Ob-kd3rrYPYHUohMSDB_cBm2RNZeu2k6buo5AAL6LTI2lfwYXLoxA_ogQfkeVadVovSz1Bw1Ea_q6Q

Kitis, E. Dimitris, Tommaso

M. Milani and Erez Levon.

2018. ‘Black diamonds','clever blacks'

and other

metaphors: Constructing the black middle class in contemporary South

African

print media. Discourse

&

Communication 12

(2):

149-170. Accessed November 5, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1750481317745750?casa_token=63iXTAzVdFMAAAAA%3A7BIvfAVliY4e6I667b55W0vSE1NQdpiss-X4_DXOuJhCGgVqKal4MaFJ6D_F4xlm_zKs5kJb1idGhw

Downing,

John.

2011. Media ownership, concentration, and control: The evolution of

debate. In The handbook of political economy of communications,

edited

by Janet Wasko,

Graham Murdock and Helena Sousa, 140-168. Chichester:

Wiley-Blackwell.

Forbes.

2018.

South Africa [webpage]. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/places/south-africa/?sh=2ebf5f40b64c

Fuchs, Christian and Vincent Mosco. 2012. Introduction: Marx is back –

the

importance of Marxist theory and research for critical communication

studies

today. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique.

Open Access

Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 10

(2): 127-140.

Accessed March 17, 2018. https://triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/421

Garnham,

Nicholas.

2011. Political Economy of Communication Revisited. In The

handbook of political economy of communications, edited by

Janet Wasko,

Graham Murdock and Helena Sousa. Chichester:

Wiley-Blackwell.

Golding, Peter and Graham Murdock. 2000. Culture, Communications and

Political Economy. In Mass Media and Society (3rd ed),

edited by James

Curran and Michael Gurevitch,

M. 15-32. London: Arnold.

Govenden,

Prinola and Sarah Chiumbu.

2020. Critiquing Print Media Transformation and Black Empowerment in

South

Africa: A Critical Race Theory Approach. Critical Arts 34

(4):

32-46. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02560046.2020.1722719?casa_token=fOMXdh6INMsAAAAA%3AdLpWKA9eomtRI0gvOoJ7Cz4iXwTes5sK28ASQ9jxUqno5cGdu1BHdYz6P3AFk7PK2AWdYqn8ZRWQ_A

Hadland,

Adrian. 2007. The South African print media, 1994-2004: An

application and

critique of comparative media systems theory. PhD dissertation,

University of

Cape Town. Accessed February 10, 2018. https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/handle/20.500.11910/6092

Humprecht,

Edda and Frank Esser. 2018. Diversity

in online news:

On the importance of ownership types and media system types. Journalism

Studies 19 (12): 1825-1847. Accessed November 15, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1308229?casa_token=uo7f8CsrV34AAAAA%3AZHgadgLnIEM8twHvhMyFKbVk-1_VsXDUGeOlyncpAqHaHZQARIVkcS-UUkPwd8Ex4Oxvqsp_pHtrfg

Knoche,

Manfred. 2021. Media Concentration: A Critical Political Economy

Perspective. tripleC

- Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal

for a Global

Sustainable Information Society 19 (2): 371-391. Accessed

October 15,

2021. https://triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/1298

Krippendorff,

Klaus. 1989. Product semantics: A triangulation and four design

theories. In Product

Semantics ‘89 Conference, edited by S Vakeva.

University of Industrial Arts, Helsinki, Finland.

Leopold, Joy and Myrtle P. Bell. 2017. News media and the racialization

of protest: An analysis of Black Lives Matter articles. Equality,

Diversity

and Inclusion: An International Journal. Accessed March 15,

2018.

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/EDI-01-2017-0010/full/html?casa_token=1nvb5GCcKhwAAAAA:52CUFrq8mrJk7yeT3im7dMqU01ZAI5Gkf1xibhQNzIailMOXCYxCH1rbiRA2_2JvD7CbMy2TcuvjnIwpWyKE1ZWqTxqZwH2VPNl0HQhBiidV-h28Rji9

Lloyd,

Libby.

2013. South Africa’s Media 20 Years After Apartheid – A Report to

the Center

for International Media Assistance. Center

for International Media assistance.

Accessed February 5, 2018. http://centerforinternationalmediaassistance.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/final_4.pdf

Masini,

Andrea, Peter Van Aelst, Thomas Zerback,

Carsten Reinemann, Paolo Mancini, Marco

Mazzoni, Marco Damiani and Sharon Coen.

2017. Measuring and

explaining the diversity of voices and viewpoints in the news: A

comparative

study on the determinants of content diversity of immigration

news. Journalism

Studies 19 (15): 2324-2343. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1343650?casa_token=kXaR0sH8o_AAAAAA%3AonDL7Cd46CrV6Tgc3sepFcj-K7eNhNthoZoPsBYk2yUQOD2BsbJGb4W-uIW9Kbljn77Xr6LgZvtn-w

McChesney, Robert. 2004.

Political

Economy of International Communications. In Who owns the Media?

Global

Trends and Local Resistance, edited by Pradip Thomas and Zaharom Nain, 3-22. London: Zed Books.

McChesney, Robert. 2001. Global media, neoliberalism, and imperialism. Monthly Review New York 52 (10): 1-19. Accessed June 10, 2018. http://cult320withallison.onmason.com/files/2014/12/McChesney_Global-Media.pdf

McNair,

Brian.

1998. The Sociology of Journalism. London: Arnold.

Melamed,

Jodi.

2015. Racial capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies 1

(1):

76-85. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/st

ble/10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076#metadata_info_tab_contents

Mosco,

Vincent.

2009. The political economy of communication. Los Angeles:

Sage

Publications.

Mottiar, Shauna and Peter Bond. 2011. Social Protest in South Africa. Centre for Civil Society. University Of KwaZulu-Natal. Accessed February 10, 2018. https://ccs.ukzn.ac.za/files/Social%20Protest%20in%20South%20Africa%20sept2011.pdf

News24.

2014.

The Living Wage and Class Struggle in South Africa (Remember

Marikana?).

Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.news24.com/news24/the-living-wage-and-class-struggle-in-south-africa-remember-marikana-20140829

Nordenstreng,

Kaarle. 1997. Beyond the four theories

of the press.

In Media & Politics in Transition: Cultural Identity in

the Age of

Globalization, edited by Jan Servaes

and Rico

Lie, 97-109. Leuven: Acco.

Obonyo,

Levi.

2011. Towards a theory of communication for Africa: The challenges

for emerging

democracies. Communicatio:

South

African Journal for Communication Theory and Research 37

(1): 1-20.

Accessed March 15, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02500167.2011.563822?casa_token=gReABklnGUgAAAAA:igBEM2c6oIimFYvbt4_mojF0lYQYCDlj2BwyxorXX8_E8bdInXr4VRouONLe8dsPrS3LrjaCe9EK

Olorunnisola,

Anthony, Tomaselli, Keyan and Ruth

Teer-Tomaselli.

2010. Political Economy Representation and Transformation in South

Africa. In Political

economy of media Transformation in South Africa, edited by

Anthony Olorunnisola and Keyan

Tomaselli.

Cresskill: Hampton Press.

Orkin,

Mark.

1995. Building democracy in the new South Africa: civil society,

citizenship and political ideology. Review of African

political economy 22

(66): 525-537. Accessed 1 February 15, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03056249508704157?casa_token=3QRkoXT_bvcAAAAA:Ujg8fJ2YinDP972XhMRFoHdfiUog8nYFXf9L2s_FUcUEyeqELITN2iWzFkfyH2Yp7VEEv2tgztAgzA

Paret, Marcel. 2017. South Africa’s Divided

Working-Class Movements. Current History 116 (790):

176-182.

Accessed February 14, 2022. https://online.ucpress.edu/currenthistory/article/116/790/176/107956/South-Africa-s-Divided-Working-Class-Movements

Radebe,

Mandla.

2017. Corporate Media and the Nationalisation of the Economy in

South

Africa: A Critical Marxist Political Economy Approach. PhD

dissertation,

University of the Witwatersrand. Accessed April 10, 2018. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/188769943.pdf

Right to Know Campaign. 2015. Media transformation and the right to

communicate report. Accessed January 10, 2018. http://www.r2k.org.za/wp-content/uploads/R2K-Media-Transformation-2015-Boolet-A5-web.pdf

Rodny-Gumede,

Ylva M. 2014. South African journalists’

conceptualisation

of professionalism and deviations from normative liberal

values. Communicare:

Journal for Communication Sciences

in Southern Africa 33 (2): 54-69. Accessed September 15,

2018. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC170577

Schudson,

Michael. 2002. The news media as political institutions. Annual

review

of political science 5 (1): 249-269. Accessed February

10, 2018. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.polisci.5.111201.115816

South African Government. 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of

South Africa. Accessed September 9, 2016. https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/Constitution-Republic-South-Africa-1996-1

South Africa History Online (SAHO). 2012. Marikana massacre 16 August

2012

[Webpage]. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/marikana-massacre-16-august-2012

South

African

Human Rights Commission (SAHRC). 2018. Kate Wilkinson: Stats about

poverty-stricken SA whites are not true. Accessed February 17, 2022.

https://www.sahrc.org.za/index.php/sahrc-media/news/item/1442-kate-wilkinson-stats-about-poverty-stricken-sa-whites-are-not%20true#:~:text=The%20reality%20in%20South%20Africa,Africans%20are%20living%20in%20poverty

Southall,

Roger.

1994. The South African elections of 1994: The remaking of a

dominant-party state. The Journal of Modern African Studies 32

(4):

629-655. Accessed June 29, 2018. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-modern-african-studies/article/abs/south-african-elections-of-1994-the-remaking-of-a-dominantparty-state/770418E367E6624270ACEDA47FCB6D3B

Stats

SA.

2019. Mid-year population estimates report. Accessed March 10, 2022.

http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022019.pdf

Steenveld,

Lynette. 2012. The pen and the sword: Media transformation and

democracy after

apartheid. Ethical Space: International Journal of

Communication Ethics 9

(2): 125. Accessed April 10, 2018. http://www.communicationethics.net/journal/v9n2-3/v9n2-3_feat2.pdf

Terreblanche,

Sampie. 2012. Lost in

transformation. South

Africa’s Search for a new future since 1986. Johannesburg: KMM

Review

Publishing.

Time.

2020.

South Africa’s wealth gap unchanged since apartheid. Accessed

February

16, 2022. https://time.com/6087699/south-africa-wealth-gap-unchanged-since-apartheid/

Tomaselli, Keyan G., and Ruth E. Teer-Tomaselli. 2008. Exogenous and endogenous

democracy: South African politics and media. The

International Journal

of Press/Politics 13 (2): 171-180. Accessed March 15,

2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1940161208315194?casa_token=HnNRRt2gAZ4AAAAA:oWXpAZBjF4AKGsCLqDsLDalJ22jMBWfY1mNoBY3AbV8j-hvt1ZiDHPT6S55sasObjhMHHPW3tLDVGQ

Warf,

Barney.

2007. Oligopolization

of

global media and telecommunications and its implications for

democracy. Ethics

Place and Environment 10 (1): 89-105. Accessed June 10,

2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13668790601153465?casa_token=DOAtPGb9dx4AAAAA%3AevUv075qRQ-6op0sv0xO_M6c9f6eAIj9HzmKqK-Phw-VbdFrUWjmfEhBAmag3-C69eaXZDVIZDwy

Wasko,

Janet.

2004. Political economy of communications. In The Sage Handbook

of Media

Studies, edited by John Downing, Denis McQuail,

Philip Schlesinger and Ellen Wartella.

Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage Publications.

About the Author

Prinola Govenden

Dr Prinola

Govenden is a Post-doctoral

Research Fellow at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study (JIAS)

located

at the University of Johannesburg (UJ). She

has

worked in various capacities in her career, most recently as a Teaching

Fellow for Wits University, Visiting Scholar at University of Oslo, and

Researcher at the Press Freedom Commission. Her

current research interests are the

intersection of power, race, and class in the modern media.