Capitalisation of the Media Industry

From a Political Economy Perspective

Manfred Knoche

Paris-Lodron-University

of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria, manfred.knoche@plus.ac.at

http://www.medienoekonomie.at

https://kowi.uni-salzburg.at/ma/knoche-manfred/

@Medoek

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manfred_Knoche

Translation from German:

Christian Fuchs

Abstract

Approaches

to the critique of the political economy of communication in society belong to

the “forgotten theories” in media and communication studies. But in view of the

unmistakable structural change of a media industry “unleashed” by deregulation,

privatisation, digitalisation, concentration, globalisation, etc., it seems

from an academic perspective necessary to analyse the development of the media

industry in close connection with the equally unmistakable general development

of an “unleashed” capitalism. This article therefore shows that the analysis of

the development processes of capitalism as the undoubtedly globally dominant

economic and social system from a political economy perspective makes it

possible to analyse, explain, and partly forecast the economisation or

commercialisation process in the media industry in an academically appropriate

way with regard to its causes, forms, consequences, and further development.

Theoretical explanations are offered by the further developments of the

analysis and critique of contemporary capitalism based on Marx’s critique of the

political economy as a historical-materialist analysis of society. In doing so, the permanent fundamental characteristics, modes of

functioning and “regularities” of the capitalist mode of production and the

capitalist formation of society are analysed in connection with the

particularities of the current capitalisation process in the media industry.

Keywords: capitalisation of the

media industry, critique of the

political economy of the media and communication, transformation, media

industry

Acknowledgement:

This article was first published in German: Manfred Knoche. 2001. Kapitalisierung der Medienindustrie

aus politökonomischer Perspektive. Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 49 (2): 177-194. Baden-Baden: Nomos. Translated into

English and publication of the translation with permission by Nomos Verlag

“Today, in my view, capitalism is for the first time in a state, in

which the logic of capital functions just as purely and unadulterated,

as Marx described it in Capital.”

Oskar Negt 1997, 38.

Introduction

What has recently been increasingly discussed in media

and communication studies as the economisation or commercialisation of the

media industry is, from a political economy perspective, an old phenomenon that

can be seen as an essential structural feature of privately organised media

production, distribution and consumption. Belonging to the commercially

organised sector of the private economy has characterised the media in

capitalist societies since their emergence (see Kiefer 1999, 705).

Nevertheless, it should be noted that it was only at the end of the 20th

century that media and communication studies in the German-speaking world

suddenly and rather astonishedly realised that the

mass media and thus also communication in society were becoming more and more

economised (see Meier 1997, 173). This astonishment could have been less sudden

or at least earlier if there had not been such widespread abstinence in this

academic field – similar to all other fields – with regard to the reception and

application of Marx's critique of the

political economy and its current developments. The currently

recognisable, partly novel (not new)

push for the economisation or commercialisation in the media industry opens up

the chance for academia that this old phenomenon’s political economy

foundations, due to their novel, more visible and thus less contestable forms,

can be recognised by more scholars than before and that academic findings that

are based on the Marxian approach can be recognised.

1. Economisation as Capitalisation of the Media Industry

However, the concept of “economisation” falls short in

the perspective of a critical political economy. Economisation is rather about

a further historical phase of the progressive “capitalisation” of the

private-sector media industry[1], i.e.

a radical subsumption of the entire

media system under the general conditions of the valorisation of capital. This

means that the media system has even more strongly than before become integrated

into the specific capitalist mode of production, the relationship between the productive

forces and the relations of production and the economic-political formation of

society (see Altvater 1999), which correspond to the

advanced stage of development and the further requirements for the survival of

capitalism as the globally dominant economic system and system of society. This

capitalisation means above all: media production is included even more

comprehensively than before in the overall economic system of capitalist

commodity and surplus-value production. Media production is thus also more

intensively subjected to the “laws of motion” and “constraints” of production

and capital valorisation, of profit maximisation and competition, as well as of

accumulation and concentration. Of relevance to society as a whole is the

further capitalisation of information, education, politics, culture,

entertainment as well as working and living conditions, which inevitably goes

hand in hand with the described developments and is usually referred to as “commercialisation”.

These commercialisation and capitalisation processes form a contribution to the

neoliberal “all-round capitalisation” (Durchkapitalisie

rung) of all areas of life (see Röttger

1997, 18f).

We are

experiencing a new push for capitalisation (Kapitalisierungsschub)

as part of the permanently progressing capitalisation process, which is,

however, of fundamental importance for the further development of the media

industry on the basis of the privatisation of originally non-capitalised

sectors. Essential characteristics of this push for capitalisation in the media

industry are

· capitalisation

through the privatisation, deregulation, and commercialisation of additional sectors of the media industry

which, organised in Europe as (monopoly) sectors under state or public law, had

not yet been accessible to direct

(but indirect) capital valorisation (radio, television, telecommunications, Internet);

· a structural

change in the media industry, which is particularly evident in the increasing

commercialisation of media content production as commodity production, in

growing international economic and journalistic concentration as well as in

economic and institutional mergers (see Knoche 1999a,154ff,

translated in English: Knoche 2016) of traditional and new media sectors with

each other and with other industries (media as infrastructure, e-commerce);

· an intensified “capitalisation”

of the relationship between the state and the media industry as well as of the state’s

media policies as media economic policies;

· an intensified “capitalisation”

of the economic and political fulfilment of the macroeconomic and societal

functions of the media industry in the worldwide structural transformation (transformation

process) of capitalism.

In view of the incalculably extensive – structurally

in part novel – “unleashing” of the media industry through deregulation,

privatisation, commercialisation, globalisation, multi-mediatisation, media and

industry convergence, digitalisation, concentration, the anonymisation of

capital, e-commerce etc., it seems to me even more appropriate than before to

analyse the development of the media industry in close connection with the

equally incalculable general development of an “unleashed” capitalism. This development

is of particular importance because the current and most likely also future

capitalisation process in the media industry is (as a novel development) characterised above all

by the fact that there is a far-reaching mutual penetration of the media

industry and the rest of the national economy.

2. Critique of the Political Economy of the Media

The fundamental significance of the progressive

capitalisation of the media industry in close connection with the development

of the capitalist economic system and system of society points to the necessity

of a critical approach that is centred on capital and capitalism (see Knoche 2016,

Prokop 2000) in communication studies that can be considered academically adequate

to the subject matter. However, as long as in the East-West conflict after the

Second World War the occupation with the critique of capitalism on the basis of

a critique of the political economy in the West also led to[2] “marginalisation”

in the academic field, or at worst to professional bans of academics, there was

no favourable “climate” for the development and reception of critical political

economy as approach for the study of the societal problem of the economisation

or commercialisation of the media industry, which had long been recognisable.

Approaches to a

critique of the political economy of communication in society or mass

communication[3] have been presented sporadically in

the Anglo-Saxon world in works on the “Political Economy of Communication(s)

(of the Media)” (see for example: Mosco 1996, Golding and Murdock 1997, Sussman

1999, McChesney 2000). Such approaches were also developed in Germany in the

1970s (see for example: Berliner Autorenkollektiv

Presse 1972, Dröge and Modelmog

1972, Holzer 1973, Hund 1976, Negt and Kluge 1972,

Prokop 1974). But the political economy of communication in society undoubtedly

belongs to the “forgotten theories” (Robes 1990, see also Knoche

1999b, 76ff). Among the attempts to remember, revive and apply political

economy approaches in German-language media and communication studies in the

1990s and around 2000 were the works by Holzer (1994), Meier (1996/1997), Meier

(1997), Knoche (2016 [originally published

in German as Knoche 1999a], 1999b), Prokop (2000),

and Steininger (2000, 210ff).

The subject of a

critique of the political economy is the critical

theory-based empirical analysis of capitalism. This shows that political

economy is not a branch of economics but a comprehensive science of society (see

Kade 1977, Schikora 1992)[4]. The critique of the political

economy is focused on the analysis and critique of the social preconditions and

structural conditions of the capitalist mode of production and thus about its

functioning and dynamics (see Conert 1997, 140). In

other words, it is focused on the analysis and critique of the “capitalist

regulation” (Kisker 2000a, 66) of the relations of

production and life, i.e. of all

economic, social, political and cultural human life. Capitalism is seen here as

a mode of production and formation of society that has developed historically and is fundamentally changeable (see Ganßmann,

1998, 23).

3. The Media Industry Under Capitalism

For our object of study, the usefulness of a political

economy as theory and method is to be examined. Such a political economy sees

itself as a further development of the analysis

and critique of contemporary capitalism. It

is a historical-materialist analysis of

society[5] that is based on the

Marxian critique of political economy. This approach has in Germany, among

other places, been developed for some time

by economists, sociologists, and political scientists on the basis of extensive

studies of the international academic literature. The focus of interest here is

the critical examination, above all, of

· the

transformation process of contemporary capitalism (see Altvater

et al. 1999, Bischoff 1999, Hickel, Kisker, Mattfeldt, and Troost 2000, Hirsch 1990), especially with a

focus on the transformation of the role of the state in capitalism (see Hirsch

1998, Kisker 2000b);

· neoliberalism (see

Bischoff, Deppe, and Kisker 1998a, Kisker 1998, Schui 2000),

Keynesianism, market myths and economic crises (see Zinn 1998);

· current economic

policy (see Hickel 1998, Huffschmid 1994);

· competition and

concentration (see Bischoff et al. 2000, Huffschmid

1994 and 2000, Kisker 2000b) and globalisation (see Altvater and Mahnkopf 1999,

Heinrich and Messner 1998, Kisker 2000a);

· the political

economy of financial markets (see Huffschmid 1999).

From a political economy perspective[6], the contemporary capitalisation of

the private sector media industry is considered and explained in the context of

the current developmental tendencies of the entire

capitalist economic and societal system. From the point of view of the

highly concentrated and internationally active private sector, the media

industry in Europe was an underdeveloped “foreign body” before the phase of

Europe-wide privatisations and deregulations, which proved to be an obstacle to

capital valorisation and capitalist expansion interests in several respects.

Monopolies organised by the state (postal services and telecommunications) or as

public services (radio and television) and non-capitalised sectors (the Internet)

were not accessible as spheres of capital investment. They could only be used

to a limited extent within the framework of infrastructural

technical-organisational rationalisation measures. They could only be “commercialised”

to a very limited extent. They did not allow extensive integration into “global”

marketing, advertising and PR strategies. The “capitalisation backlog” of the

traditionally private media sectors of press and book production, whose “disadvantage”

is still seen today in their largely medium-sized and national ties, also

proved to be an obstacle. In the interest of the economy as a whole, this “backlog”

of the media industry has been largely overcome since the mid-1980s with the

help of globally uniform neoliberal economic and social policies of the nation

states and the EU that used slogans such as the “opening of domestic markets”

and “international competitiveness”. The political-economic “backwardness” of

the media industry in Europe was similarly an obstacle for European and

especially US media corporations to realise their expansion strategies that

were necessary for their existence. There was also a “need to catch up” for

emerging European media corporations in terms of overcoming national expansion

boundaries by participating in international mergers, strategic alliances and

corporate networks of the “global players” (see Knoche 2001).

The nature,

extent, timing and course of the capitalisation of the media industry are thus

determined by the permanent economic interests and basic problems of the media

industry in connection with similar

interests and basic problems of the entire economy. However, the economic and

related political measures and medium-term strategies for solving problems,

first and foremost the problem of structural overaccumulation of capital,

regularly lead to new cyclical “crises” and long-term problems in the economy

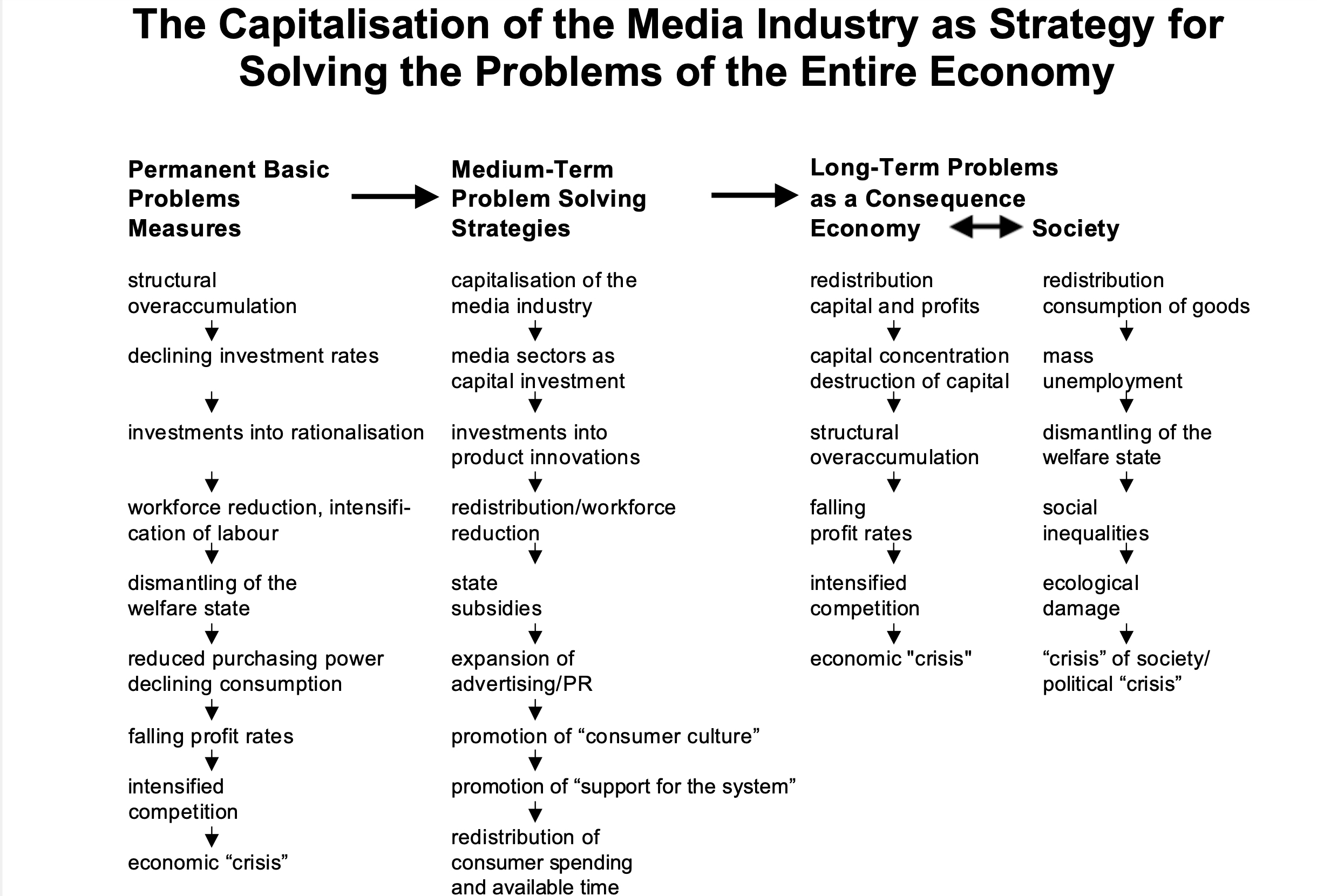

and society (see figure 1).

The reduction of

investments that enable the expansion of capital and are made under the

pressure of the structural overaccumulation of capital (declining investment

rates) and investments in (technology-driven) rationalisation regularly lead to

a reduction in the labour force (unemployment), the intensification of labour and

a reduction or stagnation of the level of wages and salaries. In conjunction

with the simultaneously enforced dismantling of the welfare state, these

developments lead to reduced purchasing power and a corresponding decline in

consumption. These developments lead in turn to intensified competition between

companies in largely saturated or stagnating markets and thus to cyclical

economic “crises” of the entire economic system.

In this context,

the capitalisation of the media industry is of growing elementary importance

for the economy and society as a whole because it also has an important

function in the necessary medium-term problem-solving strategies of the economy

as a whole. In this respect, it is explainable that the capital valorisation interests

(and their permanent fundamentally crisis-prone endangerment) in the entire

economy drive the capitalisation process of the media industry in symbiosis

with the specific capital valorisation interests in the media industry.

Figure 1: The capitalisation of the media industry as strategy for solving the problems of the entire economy

The interests of (hitherto) non-media capital are

directed, on the one hand, towards the media industry as a new profit-promising

investment sphere for over accumulated, “excess” capital. On the other hand,

these interests aim at the advertising, PR and capital circulation function of

the media, the intensive use of which is seen by the entire economy as a

necessary and appropriate problem-solving strategy in light of the crises of

overaccumulation, the decline in purchasing power, and the associated

intensification of competition.

These

media-related interests and strategies of the entire economy in principle,

although mainly represented by large corporations, are one of the triggers of capitalisation

processes in the media industry. Together with the interests of media companies,

the media-related interests and strategies of the whole economy led the

governments of the various European states to remove the obstacles to

capitalisation and commercialisation in the overall economic interest. In this

context, the legal enablement of the privatisation and deregulation of the

media sectors of radio, television, telecommunications and the Internet played

an important role. These developments increased the pressure on the media companies,

which are highly dependent on advertising revenues, to fulfil their

advertising, PR and circulation function even more effectively than before in

the interest of the entire economy and in their own interest, which is

necessary for their existence, on the basis of capitalisation and

commercialisation of media production. In connection with this, the need or

willingness of media companies to cover their capital requirements increasingly

from capital that was previously located outside the media sector or through an

initial public offering (IPO) also grew.

The fundamental

problem, however, is that the capitalisation of the media industry – even when

used as a medium-term problem-solving strategy for the entire economy – inevitably

leads to considerable economic and societal problems in the long term (see figure

1). Due to the fact that individual capitals’ action-guiding strategic goal and

interest of profit maximisation is politically legitimised and enforced as the

undisputed basic goal of capitalism, the competition

between individual capitals, which is

also politically legitimised, can only ever lead systematically to temporary

individual economic problem solutions, which in reality lead to an aggravation of problems for individual

capitals and for the economy as a whole. For there is also a redistribution of

capital and profit via the capitalisation of the media industry, which is

characterised by increasing unequal distributions: there are temporary “winners”

(concentration of capital) and (partly “final”) “losers” (destruction of

capital). But this is not a permanent solution to the problem, even for the

winners, but an aggravation of the problem, since the aforementioned permanent

basic problems of the capitalist economy (structural overaccumulation, falling

profit rates, intensification of competition) inevitably lead to the next

economic “crisis” at a higher level.

This development

also applies in a structurally similar way to the consequence of long-term societal problems, which are partly

intensified by the capitalisation of the media industry. There is a

far-reaching redistribution of consumer goods of all kinds among the

population, which, in combination with wage and salary losses, mass

unemployment and the dismantling of the welfare state, leads to a widening of

economic and social inequalities. On the one hand, this causes the next

economic “crisis” and ultimately the next socio-political “crisis”, especially

due to the associated lack of mass purchasing power. Consequently, the

capitalisation of the media industry is hardly a suitable means to solve

macroeconomic and societal problems, for example in the sense of distributive

justice for society as a whole. On the contrary: it promotes the further

capitalisation and commercialisation of the entire social and societal life

with negative consequences that will be discussed in more detail.

4. Causes, Forms, and Consequences of the Media Industry’s Capitalisation

The intensive study of the general and current development

processes of capitalism is, in my opinion, a suitable basis for the analysis, explanation and partly the forecasting of the capitalisation

process in the media industry in an academically appropriate manner that is

focused on causes, forms, consequences, and further development. The concrete

starting point is the observation that market-radicalism’s “unleashed” media

industry as an integral functional realm of capitalism is connected with the likewise

“unleashed” global transformation process of capitalism. The global

transformation process of capitalism has been characterised with keywords such

as “turbo”-capitalism (see Altvater et al. 1999), “shareholder”-society

(see Deppe and Detje 1998, 171ff), or “pure

capitalism” (Bischoff, Deppe, and Kisker 1998b, 225).

From a critical

political economy perspective, the current capitalisation of the media industry

stands in close connection with the general development process of capitalism and

the associated problems of capital valorisation in all sectors of the economy.

However, it is also important to analyse the economic-political particularities of media production,

distribution and consumption in comparison to other economic sectors. These

particularities result above all from the additional

macroeconomic and socio-political functions (going beyond the “normal”

economic function of capital valorisation that is achieved by the production

and sales of media products) which are usually fulfilled by private sector

media production (see Holzer 1994, 195):

· on the one hand,

there are the media industry’s indispensable economic functions for the entire

national economy (the function of general advertising and goods

circulation, media technology’s function in capital valorisation, the media’s

roles as a means of production),

· on the other

hand, there is the media industry’s equally indispensable ideological function for legitimising and securing the rule of the

capitalist economic system and system of society (the function of ideology

production) among the population.

· and finally, there

is the media industry’s function for the reproduction

of the labour force through media consumption (regeneration function).

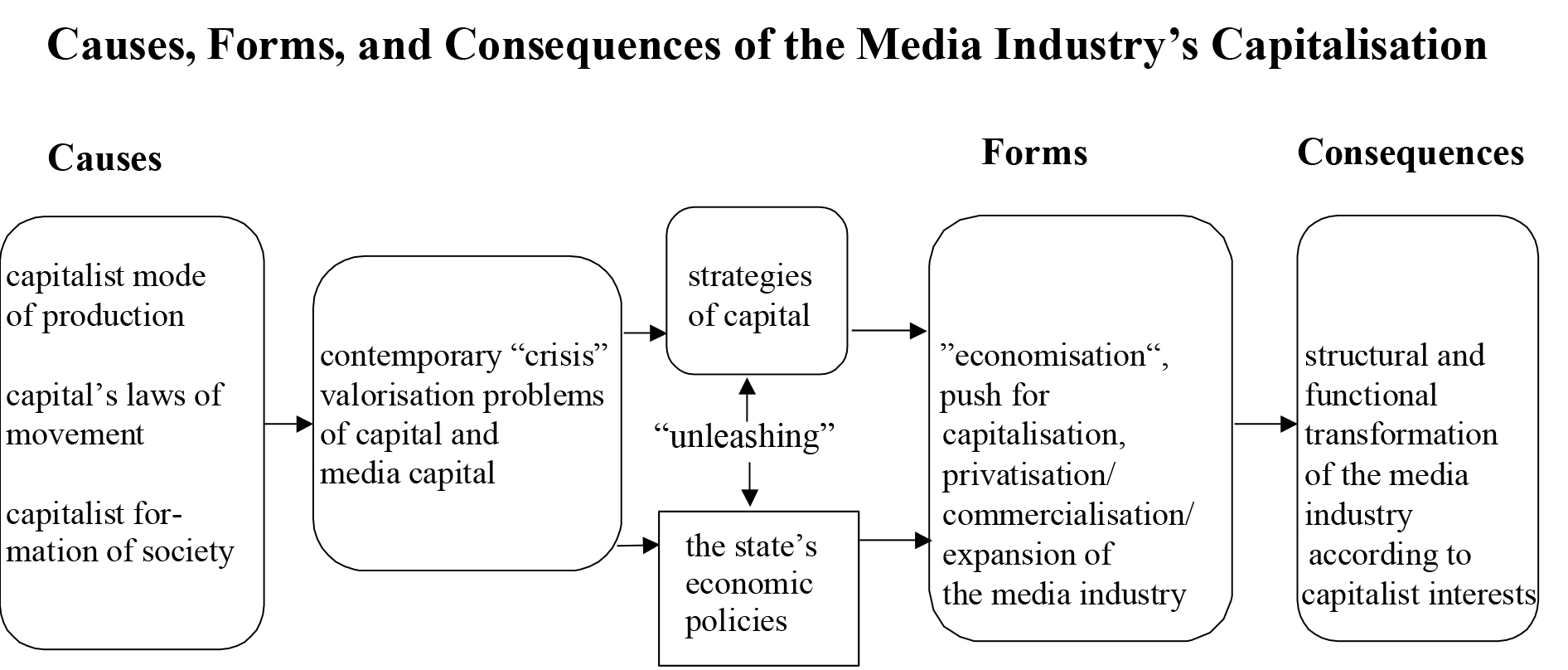

Figure 2: Causes, forms, and consequences of the media industry’s capitalisation

The connection between causes, forms and consequences

of the capitalisation of the media industry is presented in an overview in figure

2. Three complexes of causes can be distinguished as part of an interacting

bundle of causes:

· the permanently fundamental impact factors of the

capitalist mode of production and the

capitalist formation of society as

well as the laws of movement of capital

(see Altvater, Hecker, Heinrich, and Schaper-Rinkel 1999), to which the capitalist media industry is in

principle subject in the same way as other industries.

· the specifics of the current “crisis” with

the valorisation problems of capital or media capital, causally linked to the

currently observable unleashing and transformation process of capitalism.

· the concrete capital or media capital strategies interact

with the the state’s (media) economic policy that

unleashes capitalism (privatisation, deregulation, promotion of concentration,

etc.), which causes forms and consequences of the current push for capitalisation

in the media industry (see Knoche 1999a,180ff, translation in English: Knoche 2016).

4.1. Causes of Capitalisation

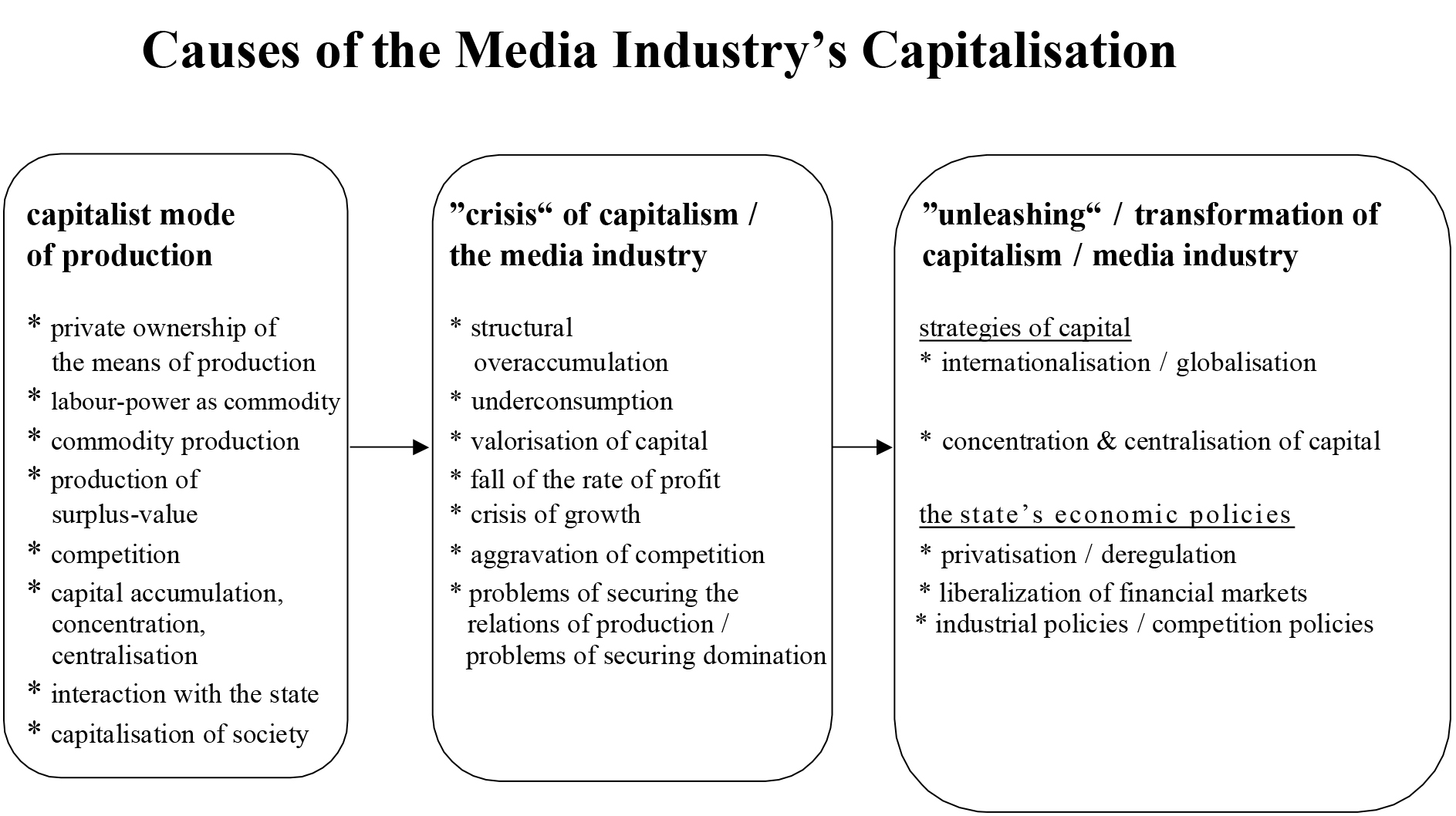

In figure 3, selected causes of the capitalisation of

the media industry are presented in more detail, the first being the factors

that are fundamentally characteristic of the capitalist mode of production (see,

for example, Conert 1997, 141; Kisker

2000a, 66 ff):

· the specific

form of the capital relation: the

legally protected private ownership of

the means of production as well as the power

of disposal over the dependent workers derived from it (labour power as a commodity) as well as

the right of the sole determination of the production

goals and the valorisation of the

produced goods by capital ;

· the specific

form of the capitalist relations of

production as relations of domination of capital over labour;

· the specific

contradictory relationship between productive

forces (the relation of constant capital = means of production and raw materials

and variable capital = labour power) and relations

of production

· the specific

form of capitalist commodity production

as the production of values (use-values and exchange-values), whereby the

realisation of exchange-value for the owners of capital dominates over the use-value

interests of consumers;

· the specific

form of capitalist surplus-value

production through capital’s appropriation of the surplus-value produced by

the surplus-labour of dependent workers

· the specific

form of the connection of the compulsion to produce, valorise and profit with the

competition, accumulation, concentration

and centralisation of capital;

· the specific

form of securing capitalist rule

through the interaction of capital owners and the state (see Nutzinger 1977, 222 ff).

· the specific

form of the capitalisation of society

via the connection of the production and reproduction process of humans with

the inequality of the distribution of goods and income and the associated inequality

of material, political, cultural and social living conditions.

Figure 3: Causes of the media industry’s capitalisation

If one takes these fundamental factors of the

capitalist mode of production into account, it becomes clear why all sectors of the private sector media

industry are in principle in the same manner subject to a

constantly progressing capitalisation process. This circumstance applies to the

sectors of the press, books, film, video, music, radio, television, for which a

new push for capitalisation can be observed in the context of the globalisation

of the entire economy and also of the media industry (see Herman and McChesney

1997, 41ff). Some large companies in the media industry – which has so far been

economically rather insignificant compared to other industries – are “catching

up” with the capitalisation level of other industries in their capitalisation

strategies. Bertelsmann AG, for example, has developed into a “media group with

an affiliated investment bank” (Jakobs 2001, 110),

i.e. for years the largest part of its profits has not been generated by media

production but by stock market deals and the purchase and sale of companies and

company shares.

Furthermore, figure

3 lists the factors that can be considered relevant causes for the

capitalisation of the media industry in connection with current crisis

phenomena of capitalism and the media industry. The development of the

capitalist economic system is generally determined to a large extent by the structural

overaccumulation of capital, which

acts as a major trigger for economic crises on the basis of disproportionate development (see Zinn

1998, 23). Disproportion means that in principle more is produced than can be

sold, i.e. that can be valorised at what is considered an appropriate profit

rate, or that less is produced due to sales problems that result in

overcapacities. Structural overaccumulation, which is signalled in particular

by over-investment, over-capacity and over-production, means that too much

capital is accumulated in relation to the realisable profit rates, so that

there is a danger of capital devaluation. The strategic action of companies is

consequently directed towards taking measures to counter the danger of crisis

that accompanies overaccumulation (see Kisker 1998,

87ff). Overaccumulation and disproportions are consequences of the competition

between the companies and the sectors that want to “win” in the competition for

the sale of their goods by overproducing beyond the demand that is

fundamentally limited by a lack of purchasing power or demand that is limited

by saturated or undeveloped needs (underconsumption).

The causes of

these limits to growth, which fundamentally endanger the valorisation of

capital, are declines in purchasing power as a result of lower wages and

salaries, unemployment, a decline in social benefits, a growing pressure to make

cuts (pensions, insurance), as well as the extensive saturation of “absolute”,

vital needs. To overcome these limits to growth and the associated dangers of

profit reductions that threaten capital, the following production strategies

are regularly used in the competition between companies in the same and

different sectors:

· the (partial)

shifting of production from goods necessary for existence and for the

satisfaction of absolute, vital needs

to products for relative needs (“validity

and prestige consumption”);

· the (partial)

shifting of production from the secondary

(industrial) sector to the tertiary

(service) sector;

· the (partial)

shifting of production from material to

immaterial goods (see Zinn 1998, 28ff).

In the application of such combined business

strategies, the media industry is generally regarded as a high-growth and profitable

economic field insofar as it opens up growth opportunities due to the interplay

of the three production strategies.

In this context,

the current process of the capitalisation of the media industry can be

explained mainly in three ways. The capitalisation of the media industry is

· firstly, for

traditional media companies, a means to solve their capital valorisation problems

associated with overaccumulation and competition, among other things by

investing surplus-capital in new privatised media sectors or in new media

markets or in media product innovations;

· secondly, for

companies from other industries/sectors/branches, a means to solve their

capital valorisation problems through increased sales-promoting advertising and

PR presented in the media; and

· thirdly, for

companies from other industries/sectors/branches, a means to solve their

capital valorisation problems by investing their surplus-capital in a media

industry that has been considerably expanded through capitalisation.

Finally, figure 3 presents another set of causes that

is relevant in the context of the “unleashing” or transformation of capitalism

and the media industry. One can speak of “unleashing”, for example, insofar as

media capital, like the rest of capital, is freeing itself from the “fetters”

of nation states through internationalisation and globalisation. A similar “unleashing”,

namely the liberation from obstacles to capital valorisation, is achieved in

particular through the privatisation and deregulation of broadcasting,

telecommunications, and the Internet in conjunction with the state’s economic

policy. Within the framework of the state’s industrial, location and

competition policies that promote concentration, the media industry is

additionally freed from obstacles to concentration (see Knoche 1996). Within

the framework of neoliberal economic and social policy, media capital frees

itself from the “fetters” of the welfare state and parliamentary democracy. For

the media industry, this means that it frees itself from the “fetters” of the

remnants of the publics service-orientation

and cultural orientation of media

production and media policy.

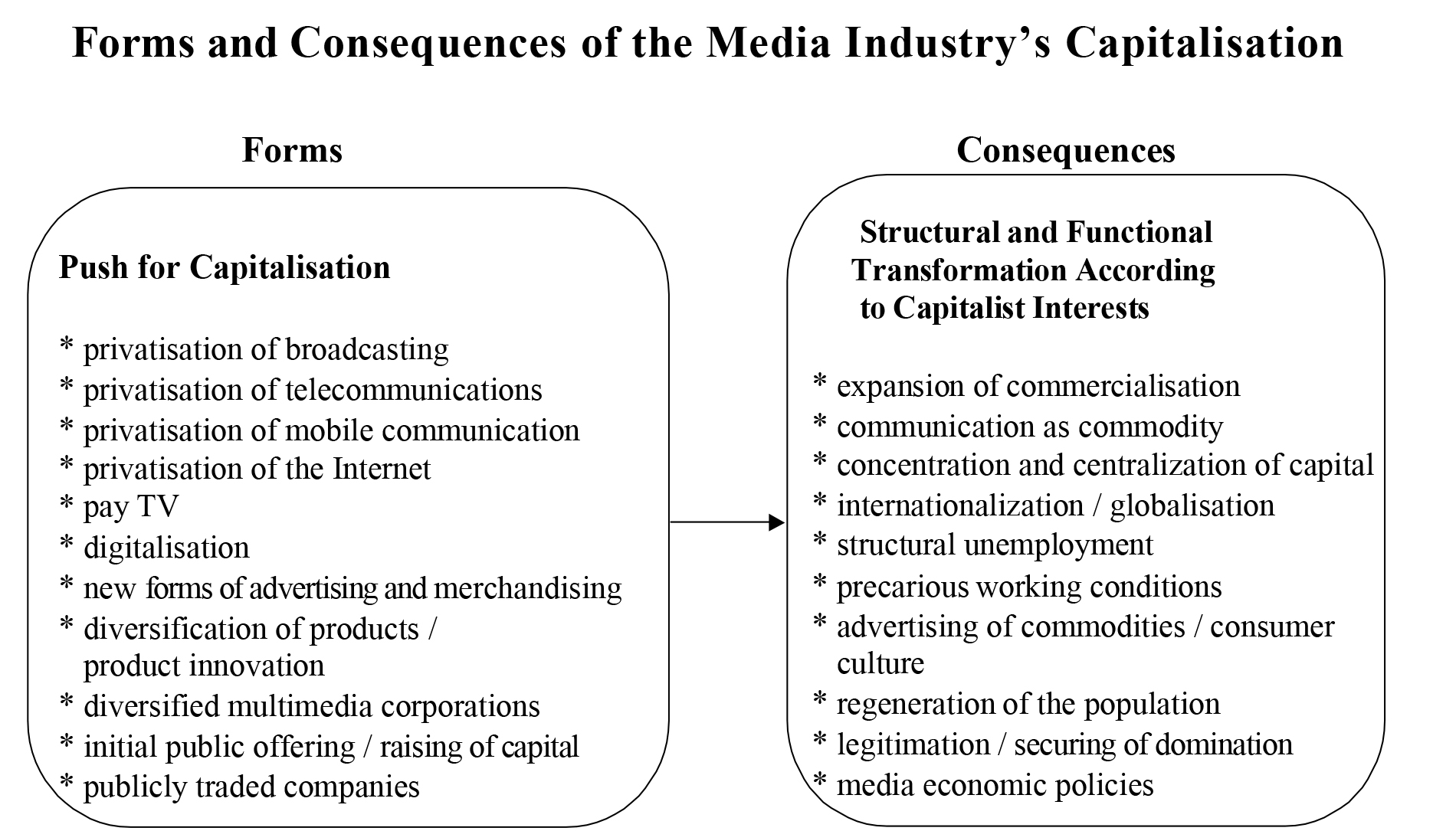

4.2. Forms and Consequences of Capitalisation

Forms of the push for

capitalisation in the media industry include, among others, the sectors

mentioned in figure 4, which in their current form are an expression of this push

for capitalisation, as well as product diversifications and innovations in the

press sector. There are forms of this push for capitalisation that can be

observed in the same way for

different media sectors. These forms include, for example, the stronger

integration of media production into the overall economic system of the capitalist

production of goods and surplus- value as well as into the system of consumer-oriented

advertising; a more intensive influence of the compulsion to produce and valorise

capital, of the compulsion to maximise profit and competition, as well as of

the compulsion to accumulate and concentrate capital. The basic similarity

(partly uneven, depending on the stage of development of the media sector) of

the push for capitalisation in the individual media sectors results from the

basic similarity of the shown causes, which in turn result from the similarity

of the preconditions – the private-sector organisational form of the media in a

capitalist economic system and a capitalist formation of society. In addition,

the similarity is shown by the fact that through technical and

economic-institutional convergence, the push for capitalisation is effective in

a media industry that is characterised precisely by the increasing dismantling

of the individual media sectors’ special features.

Furthermore, on

the level of a more differentiated analysis, one can for the different media

sectors of an expanded media and

communication industry recognise some specific causes, forms and consequences

of this push for capitalisation. In this respect, the distinction (see Knoche 1999a,

153f, English translation: Knoche 2016)

between two types of capital is important:

· media capital

used for the production or duplication of programmes and other content (the

media sectors of news agencies, the press, books, radio, audio, television,

film, video, online production), as well as

· media-related

capital and media infrastructure capital that is used only – and usually only

partially – for the production of media-related production, compression/storage,

transmission, encryption and reception technologies (in the electronics

industry, the chemical industry, the computer industry, the telecommunications

industry, the cable and satellite industry, the printing industry, the paper

industry, the mechanical engineering industry).

The media-related industries have long been engaged in

the progressive capitalisation process that is “normal” in capitalism. For example,

the companies in these industries were already suppliers of media technology

according to private-sector business principles before the privatisation of the

telecommunications sector. More novel, more comprehensive and politically much

more significant are the capitalisation processes in the media sectors where

capital valorisation is carried out with the production or duplication of programmes

and other content. Here, all the fundamental capitalisation processes mentioned

at the beginning become effective: capitalisation via privatisation,

deregulation and commercialisation of sectors of the media industry that were in

Europe previously organised by the state or as public service media, largely as

monopolies; the increasing commercialisation of media content production as

commodity production in all media sectors; the increasing influence of the

advertising industry and the integration of the media as sales media

(teleshopping, e-commerce); the macroeconomic (advertising, sales function,

consumer climate), political (political consciousness, legitimisation of the

capitalist economic system and the capitalist formation of society) and social

(regeneration of the labour force through entertainment) functions of media

production in the worldwide transformation process of capitalism.

A further

distinguishing feature for identifying tendentially differentiating

capitalisation processes is the type of financing of media production. Media

products that are financed exclusively or predominantly by advertising, one

might think, are exposed to a different capitalisation pressure than media

products that are financed exclusively by sales and distribution. However, this

view fails to recognise that media producs such as

film/video and audio (music) are also produced to a large extent in such a way

that they can serve as an environment favourable to advertising in radio and

television broadcasts. The capitalisation of the radio and television sector stands

not only in the interest of the companies involved and the advertising

industry, but also of the film and music industry. The sale of playback rights

to private radio and television companies not only creates additional sales

opportunities, but also tends to reduce the problem of the lack of purchasing power

and thus the problems of overproduction and overcapacities, since no physical products

have to be sold directly to consumers individually as in CD or video sales. An

additional variant of the capitalisation of the television sector, pay TV

without advertising, helps to solve capital’s valorisation problems that result

from overcapacities of films or film rights for which sales through

advertising-financed channels alone are not sufficient.

Finally, the

distinction between “traditional” and “new” media sectors reveals

differentiations in the capitalisation process. While some traditional media

sectors have for a long time reached a high level of capitalisation (especially

the film and music industries), the capitalisation of the Internet and online

media was in the late 1990s and around the new Millennium only in its initial

phase. There are many “strategies for the digital economy” (European

Communication Council Report 1999). Presumably the capitalisation process of

online communication will proceed rapidly as it is driven on the basis of a

high level of the capitalisation of the entire economy, including the media

industry.

Figure 4: Forms and consequences of the media industry’s capitalisation

As the most general consequence of the capitalisation of the media industry, the media

industry is subjected even more strongly than before to the general and

media-specific structural and functional changes of the economy and society in

accordance with the interests of capital valorisation. At the same time, the

media industry also influences this change. The consequences of the

accompanying expansion of the commercialisation of media production extend in

particular to

· the design of

media products as consumer goods and as commodities in competition with other

commodities;

· the expansion of

the media’s function as a means of advertising and circulating goods for the

entire economy with corresponding consequences for the content of media

products;

· the

strengthening of international capital and market concentration as well as the

globalisation of the media industry;

· the spread of

structural unemployment and precarious employment in the media industry;

· the regeneration

of the labour force according to the interests of capital;

· the creation of a

sales-promoting “consumer climate” and a political consciousness that is

aligned with capitalist interests;

· the alignment of

the state’s media policy with capitalist interests;

· the

legitimisation and securing of the domination of the international capitalist

economic system and the capitalist formation of society, especially in the

currently dominant form of neoliberalism.

5. Conclusion

Phenomena of economisation and commercialisation of

the private sector media industry were analysed in this paper as a progressive

capitalisation of the media industry. The analysis applied approaches that are

based on Marx’s critique of the political

economy and this approach’s current developments.

The

capitalisation of the media industry characterises a worldwide process in the

course of which media production is being incorporated even more

comprehensively than before into the overall economic system of capitalist

commodity and surplus-value production. The associated capitalisation of

information, education, politics, culture and entertainment is seen above all

as a contribution to the “all-round capitalisation” (Durchkapitalisierung) of all

areas of life in the course of neoliberal economic and social policies. The

capitalisation of the media industry follows the regularities that are also

effective for other branches of industry. By advancing distinctive advertising,

marketing and PR measures, the capitalisation of the media industry fulfils a

not insignificant capital and commodity circulation function within the

framework of the entire economy’s problem-solving strategies .Special features

of the capitalisation of the media industry are to be seen in the fact that, in

addition to the economic functions of capital valorisation, capitalist media

have the indispensable political-ideological function of legitimising the

capitalist economic system and the capitalist formation of society as well as the

regenerative function of reproducing the population’s labour-power through

entertainment and leisure culture. The causes, forms and consequences of the

capitalisation of the media industry do not differ in principle from those that

can be observed in other economic sectors. They can be explained in the context

of the general problems of capital valorisation and the crisis phenomena that

are permanent features of capitalist economies. It becomes clear that the progressive capitalisation of

the media industry as an irreversible process is hardly a suitable means of

promoting the fulfillment of functions in media

production that are desirable from a democratic theory perspective.

References

Altvater, Elmar. 1999. Kapital.doc. In Kapital.doc: Das Kapital (Bd.1) von Marx in Schaubil

dern mit Kommentaren, edited by Elmar Altvater,

Rolf Hecker, Michael Heinrich, and Petra Schaper-Rinkel,

12-187 Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Altvater, Elmar, Rolf Hecker, Michael Heinrich, and Petra

Schaper-Rinkel, eds. 1999. Kapital.doc: Das Kapital (Bd.1) von Marx in Schaubildern

mit Kommentaren.

Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Altvater, Elmar and Birgit Mahnkopf.

1999. Grenzen der Globalisierung:

Ökonomie, Ökologie und Politik in der Weltgesellschaft.

Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Fourth edition.

Altvater, Elmar et al. 1999. Turbo-Kapitalismus. Gesellschaft im Übergang ins 21. Jahrhundert.

Hamburg: VSA.

Berliner Autorenkollektiv

Presse.1972. Wie links können Journalisten sein? Pressefreiheit

und Profit. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Bischoff, Joachim. 1999. Der Kapitalismus des 21. Jahrhunderts.

Systemkrise oder Rückkehr zur Prosperität?

Hamburg: VSA.

Bischoff, Joachim et al. 2000. Die Fusions-Welle. Die Großkapitale

und ihre ökonomische Macht. Hamburg: VSA.

Bischoff, Joachim, Frank Deppe, and Klaus Peter Kisker, eds. 1998a. Das

Ende des Neoliberalismus? Wie

die Republik verändert wurde. Hamburg: VSA.

Bischoff, Joachim, Frank Deppe, and Klaus Peter Kisker. 1998b Licht am Ende des Tunnels? In Das Ende des Neoliberalismus?

Wie die Republik verändert wurde, edited by

Joachim Bischoff, Frank Deppe, and Klaus Peter Kisker,

225-231. Hamburg: VSA.

Conert, Hansgeorg. 1997. Zur Aktualität der Marx'schen Kapitalismuskritik. Zeitschrift Marxistische Erneuerung 31: 136-147.

Deppe, Frank and Richard Detje.

1998. Globalisierung und die Folgen.

Gewerkschaften unter falschen Sachzwängen. In Das Ende des Neoliberalismus?

Wie die Republik verändert wurde, edited by

Joachim Bischoff, Frank Deppe, and Klaus Peter Kisker,

154-176. Hamburg: VSA .

Dröge, Franz and Ilse Modelmog.

1972. Wissen ohne Bewußtsein. Materialien zur Medienanalyse der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Frankfurt a.M.: Athenäum Fischer.

European Communication Council Report. 1999. Die Internet-Ökonomie.

Strategien für die digitale Wirtschaft. Berlin:

Springer.

Ganßmann, Heiner. 1998. Soziologische Theorie im Anschluß

an Marx. In Globalisierung und Perspektiven

linker Politik. Festschrift für

Elmar Altvater zum 60. Geburtstag, edited by Michael Heinrich and Dirk

Messner, 22-36. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Golding, Peter and Graham Murdock, eds. 1997. The Political Economy of the Media. Volume 1

+ 2. Cheltenham/Brookfield: Elgar Reference Collection.

Heinrich, Michael. 1999. Kommentierte

Literaturliste zur Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. In Kapital.doc:

Das Kapital (Bd.1) von Marx in Schaubildern mit Kommentaren, edited by

Elmar Altvater, Rolf Hecker, Michael Heinrich, and

Petra Schaper-Rinkel, 188-220. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Heinrich, Michael and Dirk Messner, eds. 1998. Globalisierung und Perspektiven

linker Politik. Festschrift für

Elmar Altvater zum 60. Geburtstag. Münster: Westfälisches

Dampfboot.

Herman, Edward S. and Robert W. McChesney. 1997. The Global Media. The New Missionaries of

Corporate Capitalism. London/Washington: Cassell.

Hickel, Rudolf. 1998. Standort-Wahn und Euro-Angst. Die sieben Irrtümer der deutschen Wirtschaftspolitik. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Hickel, Rudolf, Klaus Peter Kisker,

Harald Mattfeldt, and Axel Troost, eds. 2000. Politik des Kapitals – heute. Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Jörg Huffschmid. Hamburg: VSA.

Hirsch, Joachim.1998. Vom Sicherheits- zum nationalen Wettbewerbsstaat.

Berlin: ID Verlag.

Hirsch, Joachim. 1990. Kapitalismus ohne Alternative? Materialistische

Gesellschaftstheorie und Möglichkeiten

einer sozialistischen Politik heute. Hamburg: VSA.

Holzer, Horst. 1994. Medienkommunikation. Einführung in handlungs- und gesellschaftstheoretische

Konzeptionen. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Holzer, Horst. 1973. Kommunikationssoziologie. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Huffschmid, Jörg. 1994. Wem gehört Europa? Wirtschaftspolitik und Kapitalstrategien.

Band 2: Kapitalstrategien in Europa. Heilbronn: Distel.

Huffschmid, Jörg. 1999. Politische Ökonomie der Finanzmärkte. Hamburg: VSA.

Huffschmid, Jörg. 2000. Megafusionen und „neue Ökonomie”. In Die

Fusions-Welle. Die Großkapitale

und ihre ökonomische Macht, edited by Joachim Bischoff et al., 57-74.

Hamburg: VSA.

Hund, Wulf D. 1976. Ware

Nachricht und Informationsfetisch.

Zur Theorie der gesellschaftlichen Kommunikation.

Darmstadt: Luchterhand.

Jakobs, Hans-Jürgen. 2001. „Der Deal unseres

Lebens”. Der

Spiegel 2001 (7): 110-112.

Kade, Gerhard. 1977. Politische

Ökonomie – heute. In Seminar: Politische

Ökonomie. Zur Kritik der herrschenden Nationalökonomie, edited by Winfried Vogt, 149-168. Frankfurt

a.M.: Suhrkamp. Second

edition.

Kiefer, Marie Luise. 2001. Medienökonomik. Einführung in eine ökonomische Theorie der Medien.

München/Wien: Oldenbourg.

Kiefer, Marie Luise. 1999. Privatisierung und Kommerzialisierung

der Medienwirtschaft als zeitgeschichtlicher Prozeß. In Massenmedien und Zeitgeschichte,

edited by Jürgen Wilke, 705-717. Konstanz: UVK Medien.

Kisker, Klaus Peter. 2000a. Empörung

der modernen Produktivkräfte

gegen die modernen Produktionsverhältnisse im Zeitalter der „Globalisierung”. In

Politik des Kapitals – heute. Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Jörg Huffschmid, edited by Rudolf Hickel, Klaus Peter Kisker, Harald Mattfeldt, and Axel

Troost, 65-73. Hamburg: VSA.

Kisker, Klaus Peter. 2000b. Kapitalkonzentration

und die Rolle des Staates im

Zeitalter der Globalisierung.

In Die Fusions-Welle.

Die Großkapitale und ihre ökonomische Macht, edited by

Joachim Bischoff et al., 75-99. Hamburg: VSA.

Kisker, Klaus Peter. 1998. Der Neoliberalismus

ist die Verschärfung, nicht die Lösung von Krisen. In Das Ende

des Neoliberalismus? Wie

die Republik verändert wurde, edited by Joachim Bischoff, Frank Deppe, and

Klaus Peter Kisker, 81-91. Hamburg: VSA.

Knoche, Manfred. 2016. The Media Industry’s Structural

Transformation in Capitalism and the Role of the State: Media Economics in the

Age of Digital Communications. tripleC:

Communication, Capitalism & Critique 14 (1): 18-47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v14i1.730

Knoche, Manfred. 2001. Die Folgen

globaler Multimedia-Unternehmens-Allianzen. In Forschungsgegenstand Öffentliche Kommunikation. Funktionen, Aufgaben und Strukturen der Medienforschung,

edited by Uwe Hasebrink and Christiane Matzen, 81-97.

Knoche, Manfred. 1999a.

Das Kapital als Strukturwandler der Medienindustrie - und der Staat als sein

Agent? Lehrstücke der Medienökonomie im Zeitalter digitaler Kommunikation. In

Strukturwandel der Medienwirtschaft im Zeitalter digitaler Kommunikation, edited by Manfred Knoche and

Gabriele Siegert, 149-193: München: R. Fischer.

Knoche, Manfred. 1999b. Media Economics as a Subdiscipline of Communication

Science. In The German Communication Yearbook, edited by Hans-Bernd Brosius and

Christina Holtz-Bacha, 69-100 Cresskill/NJ: Hampton Press.

Knoche, Manfred. 1996. Konzentrationsförderung

statt Konzentrationskontrolle.

Die Konkordanz von Medienpolitik

und Medienwirtschaft. In Markt – Macht

– Medien. Publizistik im Spannungsfeld zwischen gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung und ökonomischen Zielen, edited by Claudia Mast, 105-117. Konstanz: UVK Medien.

Langenbucher, Wolfgang R. 2000. Im Gedenken an Horst Holzer. Publizistik 45 (4): 500-501.

McChesney, Robert W. 2000. The Political Economy of Communication

and the Future of the Field. Media,

Culture & Society 22 (1): 109-116.

Marx, Karl. 1894. Capital:

A Critique of Political Economy. Volume III. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1885. Capital:

A Critique of Political Economy. Volume II. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital:

A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1857/1858. Grundrisse. Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough

Draft). London: Penguin.

Meier, Werner A. 1997. Zwischen

traditioneller Medienökonomie

und politischer Ökonomie gesellschaftlicher Kommunikation.

In Publizistikwissenschaftliche Basistheorien und

ihre Praxistauglichkeit,

edited by Heinz Bonfadelli and Jürg

Rathgeb, 173-183. Zürich: Universität Zürich.

Meier, Werner A. 1996/1997. Globaler

Medienwandel aus politökonomischer Perspektive. Medienwissenschaft Schweiz 1996 (2) & 1997 (1): 70-85.

Mosco, Vincent. 1996. The Political Economy of Communication. Rethinking and Renewal.

London/Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Negt, Oskar. 1997. Neuzugänge zum Marx’schen Denken. Zeitschrift Marxistische Erneuerung 30: 38-46.

Negt, Oskar and Alexander Kluge. 1972. Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung. Zur Organisationsanalyse von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit. Frankfurt a.M.:

Suhrkamp.

Nutzinger, Hans G. 1977. Wirtschaftstheorie

aus der Sicht der Politischen Ökonomie. In Seminar: Politische

Ökonomie. Zur Kritik der herrschenden Nationalökonomie, edited by Winfried Vogt, 206-235. Frankfurt

a.M.: Suhrkamp. Second

edition.

Prokop, Dieter. 2000. Der Medien-Kapitalismus. Das Lexikon der neuen kritischen Medienforschung.

Hamburg: VSA.

Prokop, Dieter. 1974. Massenkultur und Spontaneität. Zur

veränderten Warenform der Massenkommunikation im Spätkapitalismus. Frankfurt a.M.:

Suhrkamp.

Robes, Jochen. 1990. Die

vergessene Theorie. Historischer Materialismus und gesellschaftliche Kommunikation. Zur Rekonstruktion des theoretischen Gehalts und der historischen Entwicklung eines kommunikationswissenschaftlichen

Ansatzes. Stuttgart: Silberburg.

Röttger, Bernd. 1997. Neoliberale Globalisierung und eurokapitalistische

Regulation. Die politische Konstitution

des Marktes. Münster: Westfälisches

Dampfboot.

Schikora, Andreas. 1992. Politische Ökonomie. In Politische Ökonomie im Wandel.

Festschrift für Klaus Peter Kisker,

edited by Andres Schikora, Angela Fiedler, and Eckhard Hein, 11-21. Marburg: Metropolis.

Schui,

Herbert. 2000. Neoliberalismus – Die Rechtfertigungslehre für die Konzentration von Einkommen und Vermögen. In Geld ist genug da. Reichtum

in Deutschland, edited by Herbert Schui and

Eckart Spoo, 71-88. Heilbronn: Distel.

Third edition.

Steininger, Christian. 2000. Zur politischen Ökonomie

der Medien. Eine Untersuchung

am Beispiel des dualen Rundfunksystems. Wien: WUV.

Sussman, Gerald, ed. 1999. Special Issue on the

Political Economy of Communications. The

Journal of Media Economics 12 (2).

Zinn,

Karl Georg. 1998. Jenseits der Markt-Mythen.

Wirtschaftskrisen: Ursachen

und Auswege. Hamburg: VSA.

About the Author

Manfred Knoche is professor emeritus of

media economics at the University of Salzburg in Austria. He studied

journalism, sociology, political science and economics at the University of

Mainz and the Free University of

Berlin. He obtained his PhD (1978) and defended his habilitation (1981) at the

Free University of Berlin. He was research assistant in the years 1974-1979 and

assistant professor for communications politics in Berlin in the years

1979-1983. From 1983-1994, he was professor of media and communication studies at

the Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium, where he was also the director of

the Centre for Mass Communications Research. From 1994-2009 he held the chair

professorship for journalism and communication studies with special focus on

media economics at the Institute for journalism and communication studies at

the University of Salzburg in Austria, where he was the head of the department

for media economics and empirical communication research. He chaired the German

Association for Media and Communication Studies’ (DGPuK)

media economics-section. He is author of many publications on the critique of

the political economy of the media. His work has especially focused on the

critique of the political economy of media concentration and the media

industry’s structural transformations.

http://www.medienoekonomie.at,

https://kowi.uni-salzburg.at/ma/knoche-manfred/

Twitter: @Medoek

Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manfred_Knoche