Abstract: Digital platforms are a primary means of communication in

society. Public libraries play an empowering role in these processes,

strengthening citizens’ digital competences. This raises questions about

what democratic processes the digital technology is made to enable. The study investigates how a Swedish

Digital Library (DL) is envisioned and organised within a national

digitalisation strategy.

Qualitative methods are used, and a theoretical democracy framework is

developed and used together with the concepts of education and Bildung in the analysis. Four empirical

themes are identified. The analysis centres on tensions related to

horizontality and hierarchy, and Bildung

and sociality. The DL vision is dominated by a hierarchical and instrumental educational vision that connects to

representative democracy. A subordinated social and pedagogical vision

of inner motivational drives and partial forms of sharing, connected

to deliberative and semi-participatory

democracy forms, exists, mostly in the form of some cherry-picked Web

2.0 discourses.

Keywords: digital libraries, regional libraries, digital platforms, Web 2.0, gamification, peer production, collaborative production, digital sharing, Bildung, direct democracy, participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, representative democracy

Acknowledgement:

The research for this study has been financed by

the Swedish National Library as part of the research project Digital

First with the User in Focus.

1. Introduction

Fifty years after the birth of the Internet in the 1960s (Abbate 1999; Castells 2001), digitalisation is no longer considered an add-on or complement to societal institutions and public organisations. Digital tools, products and services are now expected to be a primary means of interaction and communication between citizens and the public sector. This development highlights the need for citizens to develop their digital competences and Media Information Literacy (MIL), a process in which public libraries may play an important part. It also raises questions about what kind of democratic processes digital technology enables and is made to enable. These questions are at the very core of the democracy-developing mission of libraries (Sundin and Rivano Eckerdal 2014; Rivano Eckerdal 2014).

The Swedish Library Law’s portal paragraph requires that all aspects of library work converge in democracy development, but it is not clear what kind of democracy should be developed, except for a general aim of knowledge intermediation and free opinion formation for all (Bibliotekslag 2013, 801). Should this be achieved through top-down educational initiatives directed towards individuals? Or through bottom-up Bildung based on a user’s own initiatives and practical participation, as individuals or groups, or even as communities? Different democratic forms answer these questions differently.

The study addresses the making of a Swedish national project for

digitalisation centred around public libraries and librarian-led

support for digital competence among Swedish citizens. A centrepiece

of the project is the development of the digital platform Digiteket

at the nexus of state, regional and local levels of the library

sector. The central research question of this study concerns how this

national project was envisioned and organised pedagogically and

democratically by stakeholders at the various levels.

The article proceeds with a clarification of the case study’s complex

institutional context and a background section describing prior

research into digital libraries. This paves the way for the third

section on the article’s research problem, aims and questions. The

following section presents a theoretical understanding of the study’s

central concepts. This in turn is operationalised in a subsequent

method section, which also discusses the collection and treatment of

the empirical material. The

sixth and main section presents the empirical findings from a close

reading of the empirical material. Finally, the thematised

empirical findings are analysed within the study’s theoretical

framework in a subsequent section and discussed in a concluding

section that answers the research questions.

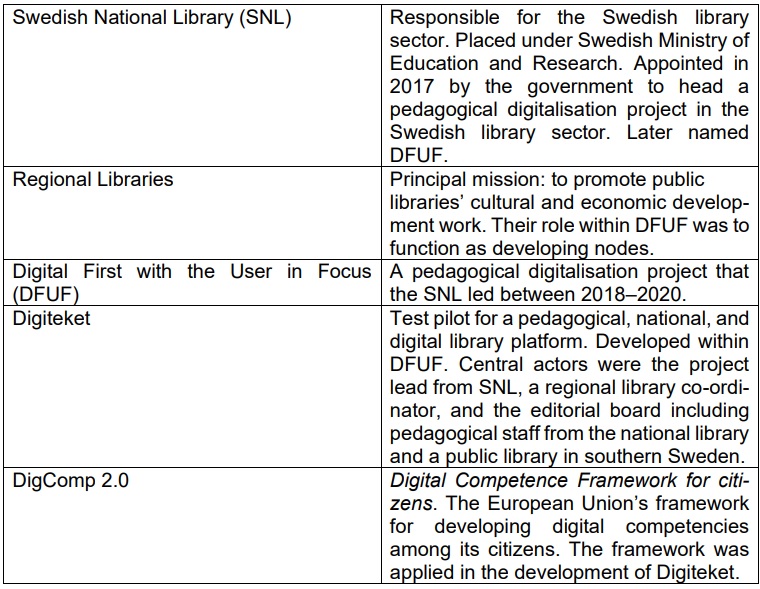

1.1.

The Case Study’s Historical and

Institutional Context

The National Library of Sweden’s

organisation and administration is under the purview of the Ministry

of Education and Research, while areas of readership and language

development within libraries fall under the Ministry of Culture. On

the one hand, regional libraries have a mission to support cultural

and economic development, while there is no regional level of

organisation for education and research. On the other hand, local

public libraries and their librarians have an overarching mission to

support democracy development.

The Swedish public library system was established in 1912 against the

backdrop of industrialisation and the formation of capitalism. The

founder, Valfrid Palmgren,

nurtured ideas of, on the one hand, the role of libraries in the

formation of democracy and Bildung for

citizens, and on the other, the nation’s need for well-educated human

capital due to the increased competition within the world market.

During this historic time, both of these concepts were accompanied by

a desire to subordinate the working classes through a societal change

firmly in the grip of the propertied class (Frenander 2012, 28). These two missions are recurring

themes in the present-day digitalisation discourse, although the class

dimension is less articulated.

In a global comparison, Sweden is one of the most digitalised countries in

the world (Andersson

et al. 2020; European

Commission 2020),

making Sweden an interesting case for research into the institutional

settings of national digitalisation projects.

The

Swedish government decided in 2015 that the public sector should be

involved in and subjected to a large-scale digitalisation project,

offering contact with citizens and companies primarily by means of

digital services. This project was called “Digital First” (hereafter

DF). The expressed aim was for Sweden to be the foremost country in

the world in this area.

In

2017, the government assigned the National Library responsibility for

a project targeted specifically at citizens in 2018–2020.

The library project was named “Digital First with the User in Focus”

(hereafter DFUF) (Uppdrag till Kungl Biblioteket

om Digitalt Kompetenslyft 2017).

The European Union’s DigComp 2.0 framework for

digital competence was applied in the project.

In

2017, the government stated that the project would be the coordinated

education (of digital competence) for public librarians in the

country. DFUF was to aim to increase the digital competence of library

staff, using regional organisations within the national library system

as nodes for digital competence and development. The regional nodes

would then mobilise the municipal libraries as hubs for the

development of the public’s competences (Uppdrag till Kungl Biblioteket

om Digitalt Kompetenslyft 2017).

The

DFUF project entailed three parallel tracks, involving the

coordinators of the regional library organisations: 1) the

Leadership track, for developing the role of regional librarians

as leaders of the digitalisation processes; 2) the Legal track,

which responded directly to the needs for greater competence in the

area of digital law and security, and 3) the Sceptics’ track,

which supported critical discussions and reflections about both

philosophical and practical experiences regarding aspects of

digitalisation and digital competences within public libraries.

Furthermore, the DFUF project also involved evaluative research in

collaboration with academic institutions around the country: this

includes the present study. The learning experiences within the DFUF

tracks and research projects have subsequently been formed into

learning materials for librarians.

One central part of the DFUF project was the establishment of a specific

digital library platform and MIL project aimed at librarians in the

Swedish public library sector. The platform was planned and set up

between 2018 and 2020 and named Digiteket.

It was developed in cooperation with Malmö Public Library (MPL) in the

most populated city municipality in Sweden’s southern region. MPL had

experience from a previous digital project for sharing pedagogical

resources among teachers. The EU’s framework DigComp

2.0 (FPFIS 2016), with its focus on improving citizens’ digital competences, was implemented

in the development of Digiteket.

Following

the spread of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, many societal

functions, stakeholders and users (both citizens and companies)

shifted to digital tools and services in line with the public

recommendations. The DFUF project and Digiteket

was thus set in a critical context.

To sum up the general organisational structure

at this time:

Table 1: Overview of the case study’s context.

2. Research Background

Having positioned the study in its historical and institutional setting, we now move to a section dedicated to research into digital libraries from the 1990s to today. This paves the way for the introduction of the article’s research problem, aims and questions.

2.1. The Digital Library: From System to Something Social?

The phenomenon of digital libraries

(DL) can be understood as a field of research and professional

practice, and as specific systems and services that are openly

accessible on several levels (Calhoun 2014). Different scholarly perspectives have shaped the DL field since the

1990s (Borgman 2000, 35; 38).

During the 1990s the computer sciences focused on DL as a

technological system providing universal access, rather than on

“institutions or objects of social influence” that permeated the

library professionals’ focus on the library users’ needs (Jones 2017, 244). Early on, the ‘digital library’ concept was criticised for obscuring

the relation between digital collections and the library as an

institution (Lynch 1993).

Around the new millennium, the US professional Digital Library

Federation (DLF) put forward one of the first definitions of DL from a

librarian’s perspective (Waters 1998). Further definitions delineate

various types of DL. One kind of DL is the central archives that

provide storage and deliver services from one single point, a second

DL form distributes its content and services over multiple network

locations that are federated, and a third type of DL aggregates the

content of many other DLs (Calhoun 2014, 24). These different systems have

varying relations to the library as institution. The relation between

technological systems of potential global outreach and regional needs

and design for different target groups include a broad array of

tensions.

Calhoun

contends that the digital transformation of libraries has generated a

shift away from a focus on (digital) collections and towards their

social role of building communities as facilitators of conversations –

a paradigmatic change (2014, 140). The ‘Web 2.0’ or social web discussion has slowly made inroads in a

digital library context traditionally characterised by higher

technical and organisational thresholds. Web 2.0 advocates propose the

development of community-centric platforms rather than

collection-centric ones (Calhoun 2014); that is, they advocate platforms that invite

and evoke user interactions for commercial reasons (Lund

and

Zukerfeld 2020).

Calhoun breaks down the social roles of DLs in relation to community

benefits in a way that indicates a tension between the social and the

individual. DLs support self-education and self-improvement,

increasing the individual’s knowledge about social, political and

community issues. The individual is in focus even when the social is

addressed. DLs also have a focus on the formal education of users (Calhoun 2014, 146-147), rather than on Bildung.

2.2. The Digital Library User: Generic or Socially Conditioned?

There is a tension in the DL field’s

discourses between a generic and cognitive view of the user and a view

of the user as socially conditioned. Computer scientists initially

worked within a system paradigm with visions of a singular universal

DL with a focus on access (Bearman 2007), whereas professional librarians adapted (and developed) technology in

line with institutional and target group needs (Jones 2017). The latter perspective is taken up

within a processual micro-sociological perspective. Here, the DL is

understood as a part of interactions between networks of technology,

information and documents, and people and their practices, often

within communities of practices. This perspective claims to connect

DLs to the world of work, production of knowledge, other institutions

and society (Bishop et al. 2003, 1; 9;

Lave and Wenger 1991).

DLs are often developed for specific user groups composed of adults with

professional information needs and access to high-speed networks (Bearman

2007). However, access

to DLs is not only a technological issue but also a cognitive and

social issue (Bishop et al. 2003), and user groups differ in their activities. Contemporary digital

platform users often take the role of producers. New concepts such as

prosumers, produsers, contribusers,

and peer producers (Benkler 2006; Lund

2015b; 2017; Lund

and Zukerfeld 2020)

reflect this development.

3. Problem, Aims and Research Questions

This section, building on the cited earlier research and contextual environment, presents the article’s research problem, aims and questions.

3.1. Research Problem

Public projects at all levels of society (international, national, regional and local) are tied to different institutional and political conditions and missions, ranging from education, research, economic growth and innovation to issues of culture and democracy. Public administration in Sweden contains an inherent tension between state-level government and the relative autonomy of regions and municipalities (Bengtsson and Melke 2019, 129; 132). This complicated institutional setup makes for a variety of focuses and creates a field of tensions that have not been widely researched in a Swedish library context.

With DFUF, the library sector is expected to operate at the nexus of

society while remaining at the forefront of digital development. This

applies specifically to the role of Digiteket,

a national DL involving the regional library organisation tasked with

the professional development and training of local public librarians.

As a pedagogical tool for digital competences, Digiteket

functions as a focal point for how the library sector envisions its

mission regarding democracy and global competitiveness in relation to

increasingly pervasive digital ICTs. This study scrutinises Digiteket’s

approach with regard to democracy .

Previous research has observed a high level of trust in Digiteket

among regional library professionals, giving rise to the reflection

that Digiteket may just be providing the

“coordinating education for the country’s public librarians”, that was

hoped for from the entire DFUF project (Lindberg et al. 2020).

This study will instead focus on the pedagogical views, sociality and

democratic visions expressed on and about the platform within DFUF.

3.2. Aims and Objective

The research aims to explore and

scrutinise the role of the DL platform and MIL project Digiteket,

and its construct, organisation and processes, within the context of a

national strategy for digitalisation and the DFUF project. The objective of the study is to shed light on which democratic visions in

particular inform the development of a nationally, regionally and

locally managed library platform aimed at fostering digital

competences on a local public library level.

3.3. Research Questions

This research question can

be broken down into two more specific questions:

1. What kinds of social interactions and pedagogical strategies do Digiteket’s project developers favour among users and produsers?[1]

2. What democratic visions do Digiteket’s project developers favour in the development of digital competences on the digital platform?

4. Theory

The previous section introduced themes such as democracy and pedagogy. These themes are theory-laden. This section presents a theoretical understanding of central concepts relating to these themes: concepts that are used in the study’s analysis section. Various democracy forms and theories are first presented and compared. The complex democracy concept is further operationalised in Table 2 in the subsequent method section. The concepts of Bildung, education and gamification are thereafter defined.

4.1. Democracy Forms

Democracy is a central concept

within the political sciences. This study’s theoretical understanding

of the concept is not comprehensive, and only strives to present a

general framework of democratic visions that span the spectrum between

two principal democratic positions in Western society: liberal representative

democracy and Athenian direct

democracy (Grugel and Bishop 2013,

22-23). Intermediary positions in the spectrum include participatory and deliberative

democracy (Dryzek 2000; Gutmann

and

Thompson 2004; Pateman 1970; 2012).

Direct democracy draws on the notion of a popular government, originally

within a Greek or renaissance republican city-state. The concept has

since been used in relation to notions of economic democracy. Rousseau

even argued for an unmediated popular government where citizens

themselves decide laws and policies. The tradition is in general

concerned with “ensuring democratic rights for the community

as a whole” (Grugel and Bishop 2013, 22). David Held first points out

political equality, direct participation and the sovereign power of

the citizens’ assembly in relation to Athens’ classical democracy, but

later connects direct democracy to socialism and communism, and the

self-regulated end of politics (2006).

Representative democracy, by contrast, draws on the notion of individual

rights, including voting rights, but with no obligations to

participate in politics (Grugel and Bishop 2013,

23; Hansson 1992, 9). Advocates of a ‘realistic’ democratic position stress that not all

citizens have an active interest in politics (Pateman 2012, 7).

The people’s sovereignty is vested in representatives who exercise

state functions, and the state and civil society are separated from

each other. Representatives come from competing factions and are

elected in regular elections (Held 2006).

During and after the 1960s revival of critical theory, theoretical

attempts were made to “go beyond liberalism or representative

democracy through participation or communitarianism” (Grugel and Bishop 2013,

36).

Advocates of participatory democracy in the 1960s had an “active

citizenry at its center” (Pateman

2012, 7).

Participatory democracy contends that voting rights and alternation in

government is not sufficient for democracy to exist. The development

of democracy is achieved by “deepening reciprocal relations of trust

between individuals”, and this democracy extends to the workplace (Grugel and Bishop 2013,

36-37), as Carol Pateman showed in a

seminal work in 1970. Pateman connected participatory democracy to

guild socialism, but also to the example of workers’ self-management

in former Yugoslavia (1970).[2]

In revisiting the theme in 2012, Pateman notes that democratic theory

has had a revival and that the term ‘democracy’ today is qualified by

a series of adjectives, of which deliberative

democracy is the most popular. The core of this position is that

“individuals should always be prepared to defend their moral and

political arguments and claims with reason, and be prepared to

deliberate with others about the reason they provide” (Pateman 2012). Deliberation is a distinctive social process in which the deliberators

are “amenable to changing their judgements, preferences, and views

during the course or their interactions, which involve persuasion

rather than coercion, manipulation and deception” (Dryzek 2000, 1).

Value pluralism, together with democratic methods and infrastructures

like polls, fora (online or otherwise), citizen juries, and

e-government’s direct access to representatives are characteristic of

this form of democracy (Held 2006).

Deliberative democracy is the conceptual successor of participatory democracy. The former is a type of participation, but in a narrower sense than the original concept (Pateman 2012, 8). Deliberative democracy’s focus on ideas and rational discussion, in contrast to participatory democracy’s more sociological position, comes close to liberalism. Gutmann and Thompson define it as affirming “the need to justify decisions made by citizens and their representatives” (2004, 3). But here differences in relation to liberalism are also found. Dryzek contends that liberalism at its core is based on self-interested individuals rather than on the common good, and that individuals are “the best judges of what this self-interest entails” (2000, 9). Deliberative democracy, in contrast, emphasises the persuasion and changing of opinions through deliberation, and the critique of established power structures, whereas traditional liberal representative democracy “deals only in the reconciliation and aggregation of preferences defined prior to political interaction” (2000, 2; 10).

4.2. Bildung and Education: a Conceptual Distinction

Bildung is a German word with two

etymological roots: bildunge

and bildunga

(Wiktionary

contributors 2019).

Olsson Dahlquist asserts that the word

contains two meanings: to build and form something in a free learning

process that cannot be imposed on the learner, and the result of that

process, understood in terms of societal or social aspirations. She

connects the first free process to a self-Bildung

ideal (självbildningsideal). The

effect or goal is not the important factor for this ideal. Instead,

the knowledge in itself has a value (Olsson Dahlquist

2019, 32-33).

Bohlin (2018) in turn makes a distinction

between two instrumental forms of education in relation to higher

university education: a narrower economic one and a broader social one

that incorporates Bildung. He contends

that today’s market ideal for higher education is to prepare students

for a profession by building their employability. At the same time, an

understanding of society as community that shares a common goal of

greater good lingers. Higher education in the latter tradition is not

only about preparing for employment in a profession but includes

developing Bildung in order to be a

citizen and solving problems for the benefit of society (Bohlin 2018,

9; 60).

The two concepts handle the tension between learning process and outcome

differently. Education always has an instrumental logic but can be

infused with Bildung in some instances.

The Bildung that is integrated in

education inherits some instrumental logic from education.

4.3. Gamification and “Sharification”

Zichermann and Cunningham (2011) describe gamification as a popular Web 2.0 technique. The concept has since gained traction in various scientific disciplines and among business professionals (Seaborn and Fels 2015). The concept has, for example, been tied to service marketing theory in pointing out its support of users’ “overall value creation” (Huotari and Hamari 2017, 25) by using non-monetary and intrinsic gratifications (Morschheuser et al. 2019). The concept’s manipulative use of intrinsic motivations in non-game contexts has been addressed from an ethical standpoint, but in an instrumental way: prescribing transparency in its implementation (Marczewski 2017). This unproblematised intermixing of external and intrinsic motivations has met with radical critique. Making a crucial distinction between playing and gaming, Lund contends that gaming (and gamification) introduce an instrumental and exploitive capitalist logic into playing that (by definition) is non-instrumental and joyful (Lund 2015a; 2015b; 2017).

The concept of sharification

used on Digiteket is modelled on the

gamification concept and relates to notions of a sharing economy that

is often portrayed in ideologically deceitful ways (Lund

and Zukerfeld 2020). Here, in

contrast, the concept is used in the management of a non-commercial

digital library.

5. Method

The study is conducted as a qualitative case study. The case in focus is regarded as a specific example of a broader societal phenomenon open to observation, interpretive exploration and critical scrutiny. The first part of the section discusses the collection of the empirical material. The second part presents the preliminary treatment and thematic analysis of the material. And the third part presents an operationalisation of the concept of democracy presented in the prior theory section. Section 5.3 aims to provide an interpretative tool for a separate and deeper analysis of the empirical material.

5.1. Presentation of Empirical Material and Collection Methods

The empirical materials used in this

case study are semi-structured interviews, continuous meetings with

the project lead, a digital project presentation, project policy

guides for content production, and the design and content of the

platform.

The interviews were conducted with project members in DFUF (names are

pseudonymised): the project lead Karin, the regional coordinator Anna,

and the editorial team, consisting of Lars, employed by the National

Library, and Erik and Anders, employed by Malmö Public Library. Lars

and Anna were interviewed on October 20, 2020 (interview 1), Erik and

Anders on November 13, 2020, (interview 2), and Karin and Anna on

November 30, 2020 (interview 3). All three interviews were conducted

on Zoom and transcribed mostly verbatim, with minor and less relevant

passages being transcribed more selectively. The continuous meetings

were held with the project lead during spring 2021 (Karin

and Anna, January 25, 2021; February 8, 2021; April 13, 2021). These meetings were used for

follow-up questions.

The policy guides for the creation of articles

and courses on Digiteket were handed over to the authors by the

informant Lars. Field notes and screenshots were collected from a

digital project presentation held by Lars, Erik and Karin for students at Södertörn

University’s Library program.

Digiteket’s design

and content are used as empirical material in several ways that

complement the views expressed in the interviews and policy guides.

This empirical material has an auxiliary function. The design and

content of the platform were investigated when they added to the

identified themes in the rest of the material. The design was

investigated by scrutinising features of the web page. Six articles

have been scrutinised in relation to how they are produced or in

relation to the themes that they address (the platforms group function

and the introduction to the concepts ‘sharification’

and ‘gamification’). Courses are only examined in relation to their

main creators.

5.2. Thematic Results Presentation

The empirical material,

transcriptions, policy documents and the presentation were first

thematised in a preliminary analysis. This

first round of

analysis consisted of a close reading of the transcriptions of the

interviews, the guides, and notes from the student presentation,

followed by identifying and coding themes at the text level that

connect to the research questions. In the second

round of analysis, the various texts were re-read and the several

identified themes from the first round were merged under an already

existing label, or under a new one. Sometimes the label was slightly

revised. In a third and

final round of analysis, some themes that did not gather

enough empirical material were merged with other adjacent themes,

others were omitted entirely as they were included in other themes,

and some were, finally, renamed. Two themes, commerciality

and copyright, were removed

for a separate article. Four themes remained for analysis: Artifact, Teaching and learning, Sharing,

and Social production processes.

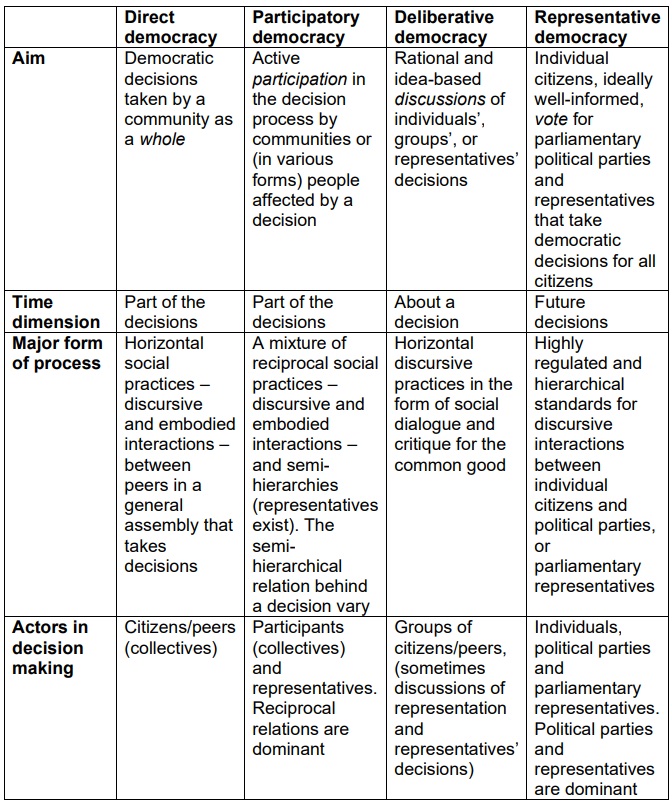

5.3. Analysis Method

This section presents a table that

operationalises the democratic forms that were introduced in Section

4. The table will be used as an analytical and interpretative tool in

the study.

Table 2: Operationalisation of theoretical positions on democracy in Section 4.

Together with this table, the concepts of Bildung, education and gamification, as defined in Section 4, are used as theoretical lenses for analytical purposes.

6. Empirical Findings

Following the presentation of the introductory, theoretical and methodological groundwork, we now present the empirical findings from a close reading of the empirical material. The identified empirical themes that will be brought to bear on the study’s research questions are: Artifact, Teaching and learning, Sharing, and Social production processes. The various parts of the empirical material – documents, interviews, and presentations – will be referred to with the following abbreviated name forms:

Article guide: (AG)

Course guide: (CG)

Interview 1 with Lars and Anna: (I1)

Interview 2 with Erik and Anders: (I2)

Interview 3 with Karin and Anna: (I3)

Presentation for students at Södertörn University by Lars, Erik and Karin: (P)

Informants’ first names will be included in reference when needed for clarity. Finally, references to the digital platform itself and the regular meetings with Karin and Anna during the spring of 2021 will be referred to in line with standard reference notation. All quotes are translations from Swedish by the authors.

The themes detected in the close reading differed depending on the source of the empirical material. The two guides did not contain as much material on the social production process as the interviews. The guides belong to a specific, instrumentally encoded genre, with greater focus on the ‘how to’, and in this case in relation to the creation of articles and courses on Digiteket. The theme Artifact is fairly dominant in these sources, and in relation to the information derived from the platform itself (AG; CG; Kungliga biblioteket 2020). It is telling that the guides do not focus at all on the ‘how to’ of cooperation or collaboration in the production of pedagogical content (AG; CG). Finally, the theme Social production processes is mainly activated in the interviews (I1; I2), prompted by the researchers’ questions.

6.1. Artifact

This theme follows two dimensions.

One concerns the design features of the platform, the other the ways

in which guide manuals portray the artifact character of the

platform’s articles and courses.

Digiteket’s

platform consists of articles and courses that are derived

thematically from the EU’s DigComp 2.0

framework. Five themes have been extracted and adapted from the

framework: information and analysis, digital collaboration, creating

content, security, and problem solving. The themes structure the

platform’s design and connect to a self-evaluation test for individual

users. The platform also has a group function consisting mainly of an

online chat function (Krämer 2020d; Kungliga

biblioteket 2020; I1; I2).

DFUF’s identification of five core digital competences have a strong

influence on the design and organisation of platform content (Kungliga

biblioteket 2020). The setup emphasises themes related to individual competences. Anna

and Lars remark that this is problematic, as there is a need to

shoehorn in new themes connected to organisational development that do

not align naturally with the DigComp

scheme (I1). Anna wants to add a sixth mixed category for

institutional and professional themes such as service design,

leadership, method development, and organisational development (I1).

These competences are more social in character.

The platform’s group function also aims to introduce social interaction (I1). In late August 2020, it was updated with clarified features. It now has a tab in the horizontal top menu, juxtaposed to the tabs of the articles and courses. The user can choose between All groups, My groups, Groups I have created, and finally the function of Creating a new group. The option of public groups was also added. (Krämer 2020d; Kungliga biblioteket 2020). The initial group function was more rudimentary. It contained only private groups, a simple chat, no digital working areas, and no uploading and sharing of files (I1; I2).

According to Anna, project members and Digiteket’s

users had already expressed a wish for an improved group function at

the project’s outset (I1). Users could not search for and find other

users’ groups: these were all private and the user had to be invited

to them. These initial design choices were made early in the project

before the editorial board had begun operations (I1). Erik says the

main aim was to avoid technological and functional complexity on the

platform (I2), whereas project lead Karin stresses practical and

administrative reasons behind the choices (I3).

The view of the digital as something complex and difficult is reflected

in the platform slogan “Digiteket: your

guide in the digital jungle” (Digiteket 2020). The digital is also visually

portrayed as something wild and slightly intimidating. This jungle

theme differs from statements regarding public librarians’ prolific

use of social media (I1). Lars mentions that “we are spoiled with

functions like these [Facebook] that can do so much more” (I1). Anna

tells us it is hard to get conversations going between librarians on

platforms other than Facebook (I1). This familiarity with digital

social media’s many social functions has not been acted on in the

design of the platform.

The personal pages for registered users were updated and personalised in

the 2020 revision. An option to upload profile photos bore the social

aim of making the identification of group participants easier, but the

remaining personalisation was individually focused on the gamification of the user experience, such as presentation of

personal statistics from the self-evaluation test and visualisations

of personal progression in completing courses within the five DigComp

areas (Krämer 2020d; Kungliga

biblioteket 2020).

Still, links exist between the visualisation of the personal page and

the group function. An award section – a subset of the statistic

display of the personal page – registers and awards socially directed

activities like creating groups, library networks, commenting, and

teamwork. Individual achievements are presented with slogans like “A

proof of your curiosity. Can you manage to reach the top?”, whereas

the group-related activities are promoted explicitly by the sender:

“We like that you build team[s]. The more the merrier”, “Work across

the borders! You will receive these awards when you create groups with

colleagues across the country”, “Communicate more! You will receive

these awards when you make your first comment in a group”, and finally

“You will receive this award when you have completed all joint courses

in a group. High five!” (Kungliga biblioteket

2020).

The Artifact theme is also articulated in guide manuals that mostly portray the platform’s content in reified terms. The article guide explains the differences between articles and courses. Articles shed light on activities and present research, courses teach skills and give technological insights; both categories may contain text, video and audio parts (AG). Of eleven pieces of advice to an individual creator on how to improve an article, ten focus on artifact aspects, and only one concerns social processes and aspects (AG). The course guide, for its part, sees Digiteket as a “knowledge bank”, aiming to achieve “uniformity in the design of the courses” (CG). The focus is on packaging “all the expertise you hold so that it reaches the users in an easy-to-handle, well-structured and pedagogical way” (CG). Everyone should be able to “recognise themselves in the course structure” that should be concrete with a clear sense of the course’s target group (CG). The editorial team also classifies and marks each course with an appropriate level of expertise (CG).

6.2. Teaching and Learning

The platform is presented as a

“guide in the digital world” to its users and 4,700 registered

members, who are mostly public librarians, except for 200 coming from

the school environment (CG; P). Its courses are presented as a

“knowledge bank” of storable learning resources, connected to the EU’s

Digital Competence Framework for Citizens’ necessary skills and

competences (CG).

The bank concept is articulated with an emphasis on standardised and

professionally designed and well-structured courses that are easy to

handle (CG). The guide itself is said to contain examples of “good

pedagogy” – a kind of benchmark reification – focused on making

“difficult material accessible in an easy way” within an

“uncomplicated pedagogical structure” (CG).

This overall instrumental perspective can be connected to the

government’s assignment description for DFUF, and to the demands of

librarians. First, the government emphasises: “competitive power, full

employment, and economically, socially and environmentally sustainable

development” (Uppdrag

till Kungl Biblioteket Om Digitalt Kompetenslyft 2017). The instrumental pedagogy is here

aligned to global competitiveness. Second, the librarians, according

to Karin and Anna, want to know the right way to do digital things.

Therefore, the people involved in Digiteket

also want to teach what is correct (Karin

and Anna, 25 January 2021).[3]

However, the Sceptic track (Skeptikerspåret), a research group related to DFUF, suggests

that the Swedish state does not have an established tradition of

educating citizens with DigComp’s

top-down approach in the library sector, with its focus on education

rather than on Bildung (I3). This

acknowledgment makes DFUF’s historic choice of the framework even more

significant.

Could it then be said that Digiteket and

DFUF prioritise instrumental education? Erik and Anders repeatedly

talk about continuing education (fortbildning).

Fortbildning has direction but is

also open-ended, continuous and ongoing. Anders states clearly that Digiteket is goal-oriented: “[Digiteket]

relates to DigComp’s 40 points […] every

course starts with what you should learn” by doing the course (I2). To

him, Bildung is something else, something

broader, that connects to important values in society that cannot

really be evaluated. Digiteket is

something else:

[I]f we

talk […] best in the digital class and so on, it is very goal

oriented. It is very clear, we should be best because it is good for

GDP, and it is a competitive advantage with the EU and so on. The EU’s

formulations are also a lot of ‘we should be best because we compete

with the US, Russia and Asia’. (Anders I2)

Digiteket’s regional co-ordinator, Anna,

defends the self-evaluation test and DigComp

as a base for personalising the platform’s recommendations of teaching

material: “this absolutely creates motivation to continuous learning”

(Anna I1). The framework has also been important in clarifying and

analytically breaking down the concept of competence (Anna I3).

But freer forms of Bildung are not totally

out of the picture. There is a desire within the project for learners

to practice “self-study” with no attached examination mechanisms (CG).

Digiteket as a site for continuing

education is dependent on the “user’s own will to learn, there are no

control mechanisms” with no external incentives and “no way for the

employer to control and extract statistics to see to what degree the

employees are continually educating themselves” (Erik I2). This

argument comes close to the concept of Bildung

as a free process. Internal motives and drives are emphasised in

contrast to external control and goals.

Lars, on the other hand, mentions that completed courses on the

platform, made visible by gamifying statistics and diplomas, will be

discussed by library managers in the traditional performance

assessments with the staff (P). And Anna mentions that public

librarians have been mandated to take specific courses in relation to

the regional libraries’ educating activities (Karin

and Anna, 25 January 2021).

The self-study processes are sometimes understood to be both individual and social within the project. For example, the use of control questions in the courses are directed to individual learners but should, according to the course guide, try to build bridges to the learner’s personal experiences and context. Control questions should be followed by recommendations for the user to discuss those questions with colleagues – explicitly colleagues at work and, less explicitly, colleagues in other municipalities (which would mean studying together on the platform) – to deepen the insights being made (CG). So, although the self-study perspective in the course guide is tilted toward the individual rather than the social study group, social forms of studying exist in the guide.

6.3. Sharing

Social dimensions can also be noted

in the strong presence of the sharing trope – “sharing thought” or

“sharing culture” – in relation to the reified learning resources in

the “knowledge bank” (I1;

I2; CG; Kungliga biblioteket

2020). This form

of sharing has its own properties. The sender and receiver of the

learning resource are not particularly connected to each other (I1;

CG). Receivers are described mainly as “readers” in the article guide

(AG).

Most often, ambitions and reality contrast with each other in relation

to social learning. Digiteket recommends

users to “study on your own or together with colleagues in your own

work place, or in other municipalities” (CG); or to build teams and

communicate more under the motto “the more the merrier” (Kungliga

biblioteket 2020),

but the rudimentarily developed group function – initially not

advocated actively by the editorial team (I1; I2) – made social

interaction difficult between librarians who did not know each other.

The sharing in the case of Digiteket mostly

takes the form of shared learning resources. The “sharing thought” and

“sharing culture” (Lars I1; I2) are never expressed in terms of

sharing resources outside Digiteket, on

other platforms. This differs from the norm of facilitating spreadable

media within the sharing industry and Web 2.0 discourses (Jenkins et al. 2013),

but gamification does exist on Digiteket.

This popular Web 2.0 technique (Zichermann and

Cunningham 2011)

connects to sharing. On Digiteket the

editorial team has invented the word “sharification”

(“delifiering”) to connect the

concepts even more tightly (Krämer 2020e).

Gamification is used by Digiteket’s

editorial team in various ways. Statistics form its central element.

Activities on the platform become registered data that mediate changes

in the user’s status, for example from Newbie to Adventurer.

Gamification is explained as the method used to achieve the goal of sharification (Krämer 2020e). Gamification, it is explained,

uses rules and internal/external motivations to change behaviours. It

contains design features such as merit badges, quests, top lists and

collectibles, and tries to activate people’s desire for social

distinction (status) and internal rewards. Digiteket’s

gamification centres on avatars, various levels of engagement and

merit badges (Krämer

2020e).

It can be seen in the award section of the personal profile pages (Kungliga

biblioteket 2020), although the editorial team admits that the gamification elements are

few and have not yet reached their purpose and function. The platform

is at an early phase, but the editors think the time is ripe for

deepened forms of gamification on Digiteket

to get users “involved and learning at the same time” (Krämer

2020e).

Gamification could in turn help to trigger positive feedback loops

from peers, motivating people to start sharing (Erik I2).

Gamification is here used to stimulate the social act of sharing in the

same way as in the commercial Web 2.0 setup, but the main instrumental

rationale is different: learning and not profit is at the centre of

attention. Lars (I1) states: “[I]f you make a course on [a] very local

level, you should think […] this could come in handy for others as

well”. The goal of sharing is mainly to make the education effort more

effective (Anna I1; Erik I2): to build more digital competences for

less money (Erik I2), and to avoid repeatedly reinventing the wheel

(Anna I1).

Another difference from the more established social media platforms is

the realisation of how difficult it is to “sharify”

or evoke sharing (Erik I2). Anna states that “[i]t

is extremely difficult to start discussions and conversations on

platforms, especially if the platform is something other than

Facebook” (I1). In future, the library sector will have to mature in

its communication on digital platforms, seeking conversations more

actively instead of waiting for email notifications (Anna I1).

Gamification is thus needed (Krämer

2020e),

yet does not seem to be enough to encourage sharing on the platform.

There are two reason why sharing is problematic. First and

foremost, Digiteket is a venue for

professional interactions and continuous education – serious

activities connected to wage labour (I2). The users are public

librarians, and the competences are ultimately locked on the state’s

need for increased global competitiveness. Professionality and the

quest for global competitiveness thus counteract sharing on the

platform. This said, the “sharing thought” that has been present all

along in the project (Lars I1) is not an unqualified form of sharing.

The sharing needs to align with the platform’s aim. Individual

librarians cannot share whatever they want, even if it is an important

goal to get individual librarians sharing resources with each other

(Anders I2). Anna even states that sharing is a “super important”

competence within the professional role of librarians (I1). This

leaves us with a paradox.

Because of professional formality the sharing fails to materialise,

yet the advocated sharing is required to be professional and formal.

Sharing is both an end itself and a means to another, contradictory,

end. Secondly, the initiation of sharing is also problematic in the

light of new legislation regarding web accessibility for people with,

for example, visual impairments. Anna points out that web

accessibility takes up large parts of both the article and course

guide, and it makes the production and sharing of learning resources

more difficult (Karin and Anna 13 April 2021).

Ideally, though, Anders would like to abolish the editor as a producer and sharer of learning resources (I2), whereas Erik stresses the need for a new, more horizontal governance model – if a Wikipedian production model were to be applied (I2). Anders, for his part, believes that editorial top-down decisions are needed for now (I2).

Tensions are thus detected in the project’s view of sharing. In relation

to these tensions it is interesting that no explicit distinctions are

being made by the informants between sharing resources and sharing

work practices on the platform (I1; I2; I3).

6.4. Social Production Processes

This section opens with some

observations and statements concerning social production processes,

listed as follows: 1) In the scheme derived from DigComp’s

framework, digital collaboration is singled out and separated from

content creation and production (Kungliga biblioteket

2020). 2) The self-evaluation test lacks focus on digital competences in

relation to the development of organisational operations (I1; Anna

I3). 3) Despite the self-evaluation test’s individual focus, the test

has helped regional libraries to identify locally needed competences

and to conduct working group discussions, and occasionally even to

jointly produce learning resources for the platform (I1;

I3; Karin and Anna, 8 February 2021).[4]

4) The course guide recommends a feature called challenges which can help spread learned knowledge “in the

workplace” with the aim of achieving “actual concrete change in the

operations” (CG). 5) The article guide advises users to let someone

else read through their article before submitting it to the platform

(AG). From these five

statements, it is implied that social production processes are

or should be going on elsewhere, typically in the library, rather than

on the platform.

Often the statements about sharing are quite general (I1; I2). The

informants do not explicitly distinguish between the dominant view of

sharing locally and individually produced resources (or ideas in the

learning process) on Digiteket, and the

sharing of social work activities (I1). The social production process

on the platform comes only close to being explicit once. Erik contends

that the goal is to attain a sharing culture which does not result in

“a technocratic ‘We do the things for you!’, but in ‘How we do things

together’” (I2).

Production could potentially be included in the concept of ‘doing’. If

so, the sharing of production processes would be seen both as a goal

and a means for a successful project. Such a position contrasts with

the design of the platform and the rudimentary group function, which

lacks social workspaces and functions for sharing files (I1; I2).

Overall, social production processes are not prioritised on the platform. Erik recalls the early discussions about platform design and the lack of social workspaces. Project members said it was “too complicated” (I2) and that such technologies would make it harder to involve – and would raise the thresholds for – the platform’s target group (P). It was better to buy already existing commercial systems, if workspaces were to be used (Erik I2). The reason behind this position was the fear of passing over the target group of the platform: the public librarians (Erik I2). This is a target group that Anna, Karin and Lars contend is less accustomed than teachers are to sharing and producing resources digitally as pedagogues, although its members are knowledgeable about social media (I1; I3). Karin, the project lead, remembers the project’s beginnings differently. She initially wanted to have a platform with shared working spaces, but this changed when MPL – already a partner to the National library – was chosen to develop the platform. Their platform concept was developed by an external software developer that wanted to scale down the design, and it was important to keep MPL as a partner. It takes time to procure a new service provider, and an ideal one would continue to curate the platform after the project was finalised – as MPL would. Karin did not want the prototype to end up as a “skeleton in the closet” (I3; Karin and Anna, 8 February 2021). Regardless of the tension in these statements, social production on the platform was not prioritised in its design.

Some minor forms of social cooperation do occur between the editorial

board, regional libraries, public librarians and other actors. During

the first outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, the

extreme situation led to the publication of three interesting articles

under the hashtag #Digitalabiblioteket: these were Digital folkbildning (Digital Bildung

for the People), Digitalt läsfrämjande (Digital Reading

Promotion), and Digitala mötesplatser (Digital Meeting Places) (Krämer

2020a; 2020c; 2020b;

Svedgård

Lindmark 2020a).

These articles were updated continuously by the editorial board, which

added local public library news relating to the three themes. It was

the editorial that took the initiative and started to collect library

examples of “meeting the users with a digital information desk”.

During certain periods there were frequent article revisions with new

content, several times a week. The news was often related to locally

produced videos, social media texts, and new digital services (I1; Krämer 2020a; 2020c; 2020b). In connection to this, the

editorial highlighted relevant courses linked to the local initiatives

and also developed new ones inspired by them: for example, on how to

livestream literature promotion activities and how to understand

copyright (I1). The coronavirus outbreak thus stimulated more

intensive interactions between the platform, its users and content

producers.

On a more granular level it can be seen that the social production

process is organised around, albeit not on, Digiteket.

The course guide mentions that it is the editorial team’s task “to

edit every course before publishing in dialogue with you as course

producer” (CG). The editorial team functions as a gatekeeper, and it

is questionable whether a dialogue between equal actors exists. The

guide stipulates that the platform user, implicitly an individual,

needs to read the entire course guide, have advanced subject

knowledge, and pass an advanced third level course on Digiteket

in order to be “able to create and teach himself” (CG). Anna admits

this “raises the threshold for sharing” (I1), but that this ideally

will change over time (Anna I1; Erik I2).

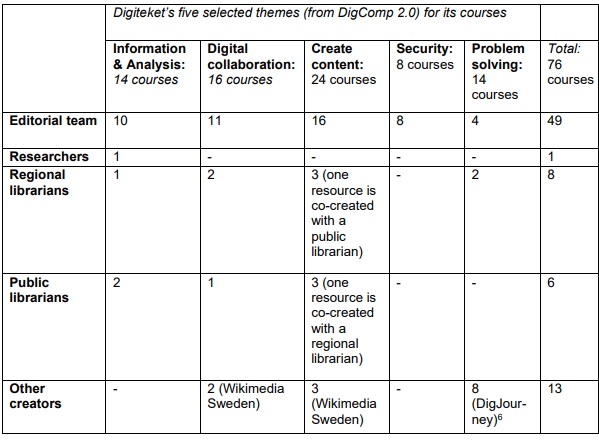

Finally, the editorial team rarely outsources work to other writers (I2) as editors usually do. The team more closely resembles a producer of learning material (Erik I2), a kind of production agency. The editorial team plays a dominant role in the production of resources. The examples mentioned above concern articles, but the pattern is also obvious in relation to the courses. Table 2 covers the distribution of the main responsible course creators on Digiteket, and the editorial team produces 49 out of 76 courses as such.[5] Regional librarians and public librarians play minor roles.

Table 3: Quantity of courses on Digiteket by creator category, February 25th, 2021 (Anna, 13 April 2021; Kungliga biblioteket 2021b; 2021a; 2021e; 2021d; 2021c).[7] One course has main creators from two different creator categories.

The informants stress that it is

difficult to organise the multi-actor production of learning resources

in the library sector, especially in relation to collective

on-platform work (I2). The New Public Management model, together with

municipal self-government (Kommunala självstyret),

makes

the sharing of work processes on Digiteket

difficult. There are many independent stakeholders with their own

budgets and missions involved (Erik I2). Further, the stakeholders do

not communicate in ideal ways (Anders I2). Introducing more collective

production processes will require a strong mandate and project

description, and firm steering (Anders I2). Erik adds the importance

of finding ways to give economic value to librarians’ active and

productive participation on the platform during labour time. It is

easy to see what is gained from Digiteket

but harder to justify a staff member’s use of two weeks for the

project on the municipality’s budget (Erik I2).[8]

The sharing paradox mentioned in Section 6.3 is valid also in relation to social production processes. Collaborative production and peer production work well in some specific contexts, such as Wikipedia or a specialised subject forum related to hobbies like fishery or Star Trek, for example: “If we are talking about enthusiasts like Wikipedians, Star Trek fans or sport fisherman fans, then there exists a tradition of sharing” (Anders I2). These enthusiasts can be prolific producers of content for a platform in their leisure time (Erik I2). However, being a teacher or librarian is too broad a category for this logic to play out: as Anders states, “I do not feel that I have too much in common with all other teachers in Sweden” (I1). Furthermore, the professional character of Digiteket is problematic in relation to peer production. Formal professional activities focused on continuous education, connected to wage labour, are at some distance from ardent fan cultures (I2).

At the same time the article on sharification

on Digiteket proposes that gamification

could potentially generate voluntary peer producers or produsers

that become so engaged and knowledgeable that they could be entrusted

with more editing powers on the platform (Krämer

2020e).

Erik contends that it would be possible to develop Digiteket

in this direction, but that it would require a new governing model and

better “possibilities for library people in Sweden to interact on the

site”(I2). Anders, on the other hand, contends that voluntary work

time on Digiteket needs to be paid in

some form or other, for example, through unemployment benefits (I2).

Erik states: “We have not solved this at all yet. It’s like

Michelangelo, we chip away [signals strokes with a chisel on an

imaginary sculpture] at the Digiteket we

would like to have in the future. It will probably be a very long

project before we can get this to work” (I2).

7. Analysis

This section provides a deeper interpretative analysis of the thematised empirical findings presented in the previous section. The analysis broadly follows Table 2 and refers to the concepts of education, Bildung and gamification as presented in Section 4.

7.1. Spectrum Between Horizontality and Hierarchy

The initial rudimentary group function on Digiteket created a narrow kind of group sociality which allowed for the free creation of private groups. It came with a hierarchical feature distinguishing between invited and non-invited platform users. The private groups and the chat feature point – albeit weakly – towards a dialogical and deliberative direction of horizontal discussions, but the hierarchical feature points in the opposite direction.

The 2020 revision introduced public groups that were searchable and

visible for all interested platform users. The default option was

still private groups, but the horizontal character and the

similarities with deliberative democracy were strengthened when

private and indirectly hierarchical groups were challenged by a public

option.

In the revision of Digiteket the user profile pages were gamified. Awards were given for specific achievements and were accompanied by slogans. One was “We like that you build team[s]”. The ‘We’ refers to the editorial team. It speaks to all the users from a privileged position similar to the position of representatives vis-à-vis citizens. More hierarchical and limited forms of participatory democracy including grains of representative democracy also align with the slogan.

Looking at the platform’s content, the guidelines see Digiteket

as a professionally well-structured and assessed “knowledge bank”. It

is a standard for (in)forming and educating individuals in particular

in standardised competences laid down by the EU. This leads to high

thresholds for participating in the production and sharing of learning

resources. None of the activities are unqualified: you cannot do and

share exactly what you want on the platform. Ideally, this leads to

low thresholds for participating as receiving and studying learners.

The advocated “sharing culture” is mediated by this digital knowledge

bank, and it is a hierarchically structured, interrupted form of

sharing. The sender is a course producer professionally accepted by

the editorial team, whereas the receiver is a more passive ‘reader’ of

the resource. The sharing does not initiate dialogical deliberation,

except vaguely and implicitly between students at the receiving end

(contradicted by the group function’s status). It is also focused on

so-called spreadable media, rather than on working together and

sharing work processes on the platform. It is this sharing – sometimes

with gamification as a proxy – that is advocated and initiated by the

editorial team and project members.

Finally, the platform is also presented as a guide to the digital

jungle, and it talks to its subjects and teaches them, as shown in

Section 6.2. The instrumental DigComp

framework is embraced by the informants as part of a pedagogical

effort labelled as continuous education. The concept connects to

education and goal-oriented forms of Bildung.

The fixed competences, added externally from the EU or in the name of

global competitiveness, are for the individual learner to conquer and

win. To Anna, this ongoing quest creates a motivation to learn.

These top-down views align well with the aim and processes of

representative democracy and its highly regulated hierarchies, as well

as with the instrumentality of education. It is hard to become a

pedagogical producer, and hard to become a decision-making

representative. The participants rarely take part in the teaching,

just as the voter seldom takes part actively in the decision-making.

Forms of participation are limited, predominantly confined to studying

as an individual, in the same way that one votes alone. No real

deliberation is supported between the sender and the receiver of

learning resources. The focus is on the individual receiving education

from professional educative sources, approved by professional

decisions, much in the way that citizens’ individual voting is based

on political parties and representative-approved messages.

The statement that standardised goals for standardised competences

creates an inner motivation to learn, together with a defence of the DigComp-derived framework, plays down possible

problems with hierarchical and instrumental education, embracing the

learning of competences that emanate from the needs of alien

institutions. The creation of well-informed librarians is favoured,

rather than the librarians’ freer Bildung.

This implicit reference to global competitiveness is, in its

standardised and hierarchically imposed character, possibly linked to

structural features of representative democracy. Indirectly,

parliamentary democracy is the dominant democratic form of capitalism,

and both are strongly tied to each other in liberal thought.

Digiteket’s

group function connects to limited forms of direct, participatory, and

especially deliberative democracy within small private groups. This

undercurrent contrasts with the overall project’s hierarchical

management, focused on individual students and instrumental education

based on professionally standardised learning resources. The initial

design decision, referred to above, to keep the group function simple

– either because of a lack of trust in librarians’ digital competences

or out of administrative considerations regarding the development of

the platform – points to the undercurrent’s minor position.

Potentially, these top-down views could be applicable to a

hierarchical and limited participatory democracy that embraces a very

goal-oriented Bildung. But the emerging

picture clearly speaks against more horizontal forms of participatory

and deliberative democracy.

7.2. The Role of Professionality

The guides see Digiteket

as a professional, well-structured and well-assessed “knowledge bank”,

a standard used for (in)forming individual professionals. This leads

to high thresholds for participation in the production of learning

resources, and in that sense also for learning to be a pedagogue by

doing or practice: by being part of the teaching. The concept of a

knowledge bank translates quite literally to the banking

concept that critical pedagogical theory and critical

information literacy in the tradition of Paulo Freire are criticising

for its alienated and fragmentised form (Downey 2016).

But the individual focus of the DigComp’s

framework used here is also criticised within DFUF. A more social

perspective is needed within the educational framework as a complement

to the individual focus. This social alternative is institutional and

instrumental in character and expressed as organisational development

in the library sector. Librarians

should be pedagogically (in)formed so that they can respond to the

sector’s needs.

Digiteket’s

pedagogical effort is framed as part of a continuous education. The

concept connects to both instrumental education and goal-oriented Bildung (as Bohlin (2018)

describes); although it is predominantly fixed competences that are to

be conquered. Anders relates these competences explicitly to global

competitiveness.

The platform’s feature as a guide and the editorial team ‘talking to’

its target group as a gatekeeper add to the two intertwined aspects of

a professional and standardised knowledge bank, and a dominant

instrumental and external (as regards individual students) education

or non-free Bildung. The sharing on Digiteket is not unqualified. You cannot do

and share exactly what you want. The shared resources have to fit the

platform’s aims and professional standards. This is a hierarchical

regulation reminiscent of representative democracy’s standardised

demands on political parties and actors taking part in the public

sphere.

The ‘representative’ of representative democracy is a professional with

a distinguished position. The concept of ‘profession’ could be

understood as acting out a function, or fencing in an expertise area

in which professionals have a monopoly (Brante et al. 2009;

Nolin 2008; Wisselgren 2018).

Non-professionals, amateurs and students, or voters, are positioned

outside the function or expertise area. Interestingly, it is precisely

the professional librarians that are positioned on the outside in the

empirical material of this study, being subject to sanctioned actions

by the representatives of the editorial team. Participation is not

horizontal between equals, but hierarchically structured.

These positions mainly connect to the aims and processes of representative democracy, where citizens ideally should be educationally well informed in the eyes of an external system that implicitly places demands on the individual (voter or librarian). Once again, a top-down view could potentially apply also to limited forms of hierarchical participatory democracy.

7.3. Instrumental Personalisation

The previously mentioned

personalisation of profile pages obviously concerns individuals. The

personalisation works within the DigComp

framework, operationalised through the self-evaluation test for

individual users: a standard for the individual to be measured

against. This framework will potentially be complemented by themes

related to organisation development, which would shape the character

of personalisation on the platform. It is unclear from the material

how these themes would be designed, or by whom. During DFUF’s

existence, it was the project members that took these decisions at a

national level.

The progression of being informed on Digiteket

is visualised and gamified with personal metrics and statistics

surrounding the self-evaluation on the site. “Can you manage to reach

the top?”, the award section asks, putting a strong educational or Bildung instrumentality in play. However,

social ambitions also leave traces in the personalisation work. To

promote the group function, as well as group creation, slogans like “Communicate more!” and “Work

across borders!” are used on the personal profile pages.

Personalisation can thus have deliberative and collaborative ends. And

in this case, as has been mentioned (see Section 7.1), it is the

editorial team that gives the advice.

The gamification strategy in the personalisation work is actively

connected with sharing, sharification and

the creation of a sharing culture on Digiteket,

much in line with Web 2.0 ideology. Individualism should thus foster

sociality in the sense of sharing resources on the platform. One

informant thinks that the time is ripe for a deepened form of

gamification on Digiteket, with the goal

of getting users involved and learning at the same time.

Another angle of instrumental personalisation is expressed in the wish

for the platforms’ learners to practice self-study. This self-study is

thought to be free in the absence of external parties’ examination

mechanisms, but one informant stresses that librarians have been

mandated to do platform courses by their employers, while another

hints that activities on the platform will be used by employers in

their evaluation of their staff. Thus, even if the learners’ inner

drives are emphasised, the overall standardised instrumentality

transforms them into directed inner drives, open for and actively

engaged in others’ standardised education. This can be understood as a

slightly non-alienated education, or as an instrumental non-free Bildung.

The guidance regarding self-study is further centred on specific forms

of deliberation organised by the courses’ control questions. Together

with standardised and professionally controlled learning resources,

this introduces a hierarchical dimension in a discursive practice that

otherwise connects to deliberative democracy.

The individualism in the above examples resembles the individualism of representative democracy. The shaping of the individual’s inner drives to learn external categories, either from DigComp or from the profession, bear similarities to the shaping of voters’ conditions with a political party system in representative democracy. Both kinds of external categories should ideally be (self-)studied by the individual learner or voter. They provide a standard to measure individual conceptions against – in internalised and externalised forms. Personalisation and gamification (even when it propagates sharification) are subordinated to this educational instrumentality of making the librarian or voter well-informed in accordance with externally set categories. The radical critique of gamification as detrimental for joyful play and, if stretched, voluntary and intrinsic Bildung processes, is not reflected in the material; rather, the opposite is true.

7.4. The Character of Co-operation

The structuration of Digiteket’s

articles and courses are derived from the EU’s DigComp

framework, which is focused on individuals’ competences. Hierarchy, in

combination with a traditional political institution as an origin,

points toward the category of representative democracy, especially in

relation to the processes and actors involved. One of the Digcomp

framework’s themes is ‘digital collaboration’, which could indicate an

affinity with direct and participatory democracy; but this social

track is minor in the overall picture. Digital collaboration is also

understood as something other than producing content, which limits the

intended level of participation. Producing together on the platform is

not explicitly sought.

Looking at the group function, the 2020 revision introduced the option

of public groups that were searchable and visible for all interested

platform users. Even if this broadened the platform’s sociality, the

group function still only consisted of a rudimentary chat. Despite

this, the function leaned toward deliberative democracy, rather than

toward direct and participatory democracy, since the function lacked

common workspaces and uploading options that facilitated more embodied

(albeit digital) cooperation.

Social cooperation related to the platform also takes the form of

communication between the editorial team, regional and public

librarians, and other actors, although this is a communication style

where the editors are gatekeepers with high standards for the content

in a way that differs from Web 2.0 discourse or peer production. In

this process, the editorial team takes on the role of a production

agency, a small, tight content producer group that initiates and

collects information about news related to the local production of

learning resources. The deliberation is not a dialogue between equals,

and the communication has hierarchical features reminiscent of

representative democracy’s institutional top-down processes.

The statement that the group function was kept technologically simple

because of a doubt of public librarians’ digital competences, although

downplayed by the project lead’s emphasis on path dependencies and

administrative concerns, implies high standards for collective forms

of participation on the platform. Participation as in social

interaction is often placed outside of the platform. The

recommendation is for platform-based self-study of a type that would

frequently herald a collegial discussion at the librarian’s workplace.

The social interaction is thus discursive and influenced by Digiteket’s

resources but placed within practical library operations in the

workplace. At other times, socially produced material at the local or

regional library level is aimed at the platform. From Digiteket’s

perspective, digital collaboration is thus not primarily about

socially producing content on

the platform but sharing it.

The sharing of approved and standardised learning resources on Digiteket

is a limited form of participation, mediated by a digital platform

perceived as a knowledge bank. It does not build on or build a

connection between the sender and receiver. The sender is a

professionally accepted course producer, and the receiver is a more

passive reader of the resource. The two do not meet each other in the

asynchronous interaction. Sharing in this form is not equivalent to

the gift economy’s creation of sociality. Lewis Hyde once talked about

the gift that goes around, the act of gift-giving leading to the act

of returning the gift, gradually expanding sociality (Hyde 2012).

This logic characterised early peer production (Benkler 2006; Lund

2015b; 2017),

but the Web 2.0 sharing industry transformed and reified the processes

into a sharing of “spreadable media” on many different platforms (Jenkins

et al. 2013; Lund

and Zukerfeld 2020). The sharing concept is thus broadly ideological (Lund and Zukerfeld

2020; Miller 2011; Scholz

2016). This

sharing is focused on product and commercial logics, rather than on

social gift-giving. It is this sharing of professional and

standardised content, albeit non-commercial content shared only on one

platform, rather than the sharing of work processes (working together)

that is referred to in the context of Digiteket.

It is a sharing without sociality in a deeper sense. In the

interviews, one informant does think that sharing is about learning