1.

Introduction

Human activity over the last few centuries has been and still is leading to unprecedented climate change, biodiversity loss, and other ecological degradation. For an increasing number of scholars, the socio-economic system of capitalism and its mode of production is the main driver of this ecological degradation and climate change, as well as of social inequality (see e.g. Foster, Clark and York 2010; Moore 2015; Saito 2017). Degrowth as a radical transformation-seeking discourse and movement opposes the capitalist imperatives of perpetual growth and capital accumulation (Kallis, Demaria and D’Alisa 2015). Degrowth seeks to fundamentally transform society to be both environmentally and socially sustainable. The main aim of degrowth is to reduce human economic activity (i.e. consumption and production) to sustainable levels, while increasing wellbeing (Robra and Heikkurinen 2019; Schneider, Kallis and Martinez-Alier 2010), as current levels of economic activity are leading to an ecological footprint that exceeds the carrying capacity of the planet (Rockström et al. 2009; Hoekstra and Wiedmann 2014). Degrowth is in stark opposition to the dominant capitalist paradigm and hence represents a counter-hegemony to capitalist hegemony (Buch-Hansen 2018; D’Alisa 2019).

Gramsci’s (1971) concepts and terminology of hegemony and counter-hegemony are increasingly used in describing how degrowth opposes the political economy of capitalism (see e.g. D’Alisa 2019; D’Alisa and Kallis 2020; Kallis 2018). Yet this political economic perspective has found little analytical application in the context of economic organisations and degrowth. Indeed, despite increasing interest in and research into the discourse of degrowth, micro-economics and economic organisations have generally received little research attention (Nesterova 2020; Shrivastava 2015). An economic organisation is defined in this article as an entity (such as a business, firm, corporation or cooperative) that focuses on the production and distribution of tangible as well as intangible goods.[1] Over the last two or three years, more studies have emerged that examine economic organisations from a degrowth and post-growth perspective (see e.g. Gabriel et al. 2019; Hinton 2020; Khmara and Kronenberg 2018; Nesterova 2021; Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova 2020; Hankammer et al. 2021). However, even in these more recent studies the political economy of capitalism is addressed only briefly, if at all.

Ergene, Banerjee and Hoffman (2020) call for a stronger emphasis on political economy when studying economic organisations. For degrowth to fulfil its counter-hegemonic role it is vital to consider its political economic implications for economic organisations. Alternative modes of production and economic organisations play significant roles in overcoming capitalist hegemony. However, alternative modes of production (and thus also economic organisations using these modes of production) face the contradiction of society’s economic relations and processes underpinning the capitalist mode of production (Marx 1867/1969). It is therefore vital to understand the distinct roles of economic organisations and modes of production, as well as the interplay between them, in helping to achieve a degrowth society while facing this contradiction. Various alternative economic organisational forms have been connected to degrowth, such as cooperatives (Blauwhof 2012; Johanisova, Padilla and Parry 2015), social enterprises (Johanisova, Crabtree and Fraňková 2013), and commons-based peer production (CBPP) (Kostakis et al. 2018; Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova 2020).

CBPP is particularly interesting in the context of degrowth counter-hegemony. It is not only a form of economic organisation (that is, CBPP organisation) but also a mode of production potentially able to help overcome capitalism and its mode of production (Bauwens, Kostakis and Pazaitis 2019).[2] CBPP is a distributed and asynchronous form of organising production whose operations are based neither on strict management nor on market signals (Benkler 2007). It represents a mode of production based on open knowledge, software, and design freely shared as commons (Benkler 2007). Combined with distributed manufacturing capabilities, CBPP can enable shared capacities for adaptable, customised and reproducible solutions and artefacts, which are fit for individual or local needs. These characteristics of CBPP have been shown to bear the potential to support degrowth (Kostakis et al. 2018).

Despite a tentative link between CBPP and degrowth, CBPP does not automatically represent a mode of production that helps to achieve degrowth (Kostakis et al. 2018; Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova 2020). Whether and how CBPP can help degrowth to overcome capitalist hegemony needs to be closely investigated at the organisational level. In other words, economic organisations using CBPP as their mode of production must be investigated. To this end, this article seeks to empirically study how CBPP organisations can align with degrowth counter-hegemony and reproduce it. Such an investigation also requires an appropriate organisational theory, as classical organisational theories are heavily influenced by business and management studies and are hence more aligned with capitalist hegemony. Furthermore, these theories often fail to fully conceptualise organisations within the complexity of the wider social system (Luhmann 2018); this conceptualisation is arguably required to analyse economic organisations in the context of hegemony and counter-hegemony. Seidl and Becker (2006) argue that Luhmann’s social systems theory has the unique potential to analyse organisations within the complex setting of the societal system.

We thus attempt to use Luhmann’s (2012) social systems theory as a theoretical lens to examine economic organisations in connection to the wider social system that is society. As the name implies, Luhmann’s (2018) theory conceptualises organisations as social systems that communicate decisions to constantly reproduce themselves (Seidl and Becker 2006). Specifically, our focus is on decision premises, that is, previous decisions that are used as the foundation for future decisions. This has been proposed as an effective approach to use social systems theory for empirical research on organisations (Besio and Pronzini 2010). Therefore, this article aims to explore two cases of CBPP organisations, namely P2P Lab and Wind Empowerment, to answer the question: Do commons-based peer production organisations demonstrate counter-hegemonic degrowth in their decision premises? If so, how?

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the theoretical framework for the study by providing a more in-depth description of degrowth as counter-hegemony (2.1.) and CBPP (2.2.), before elaborating on how social systems theory can be used to observe organisations (2.3.). The methodological approach for multi-case study research is described in Section 3, while Section 4 presents the findings of the case study. Finally, Section 5 briefly discusses the findings and concludes with potential future research avenues.

2.

Theoretical Framework

2.1.

Degrowth

Counter-Hegemony and Economic

Organisations

The pursuit of perpetual economic growth has dominated the political agenda since the beginning of the 20th century (Dale 2012). Economic growth is commonly viewed as the driver and often the prerequisite of prosperity, wellbeing and happiness (Jackson 2011). However, over the latter half of the 20th century, wellbeing in, for instance, the Global North has largely levelled off, despite continuous economic growth (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009). Simultaneously, the severe effects of continued economic growth on the social fabric and the environment have persisted (Kallis 2018). The stark contradictions of endless growth on a finite planet have been decried since the 1970s in the work of Georgescu-Roegen (1971), which heavily influenced the well-known report The Limits to Growth by Meadows et al. (1972). Other scholars such as Illich (1973/2001) and Gorz (1994) have advanced critical approaches to growth, gradually shaping degrowth scholarship.

Degrowth’s influences expand beyond economics and political economy to include environmental justice movements, which overlap with the post-development discourse (Escobar 2015). Hence, degrowth’s critique on the pursuit of endless economic growth concerns both the ecological destruction caused by the latter and its adverse effects on society. The aim of degrowth is not the reduction of economic growth in the form of, for instance, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) decrease per se (Kallis 2018). Rather, it recognises that the endless pursuit of economic growth also requires endless increases in economic activity which, in turn, demands constant increases in material and energy throughput[3] (Robra and Heikkurinen 2019). Hence, degrowth aims to reduce society’s matter-energy throughput to sustainable levels while increasing and maintaining wellbeing (Schneider, Kallis and Martinez-Alier 2010). Further, degrowth’s aims are aligned with the understanding that to achieve wellbeing and social/environmental justice a complete transformation of society’s structures is required. Current societal structures have co-emerged with a focus on economic growth and capital accumulation and are heavily reliant upon these (Büchs and Koch 2019). Therefore, degrowth envisages a society able to prosper without continued economic growth (Kallis 2018).

Degrowth is often misinterpreted as aiming solely to reduce economic growth. This may stem from misunderstanding the missile slogan that degrowth represents in order to repoliticise the debate around growth (Latouche 2009). However, a reduction in matter-energy throughput will likely lead to reductions in economic activity and growth; in fact, this outcome is physically inevitable. Yet to argue that degrowth solely aims to reduce economic growth is a gross simplification of the complex societal transformation degrowth seeks to achieve.

Economic growth must be understood in the light of capitalism’s core imperative of capital accumulation. Despite its different forms, as a societal structure and system, capitalism requires and enables capital accumulation (Foster, Clark and York 2010). Capital accumulation is the engine of economic growth, which in turn enables further capital accumulation (van Griethuysen 2010). Capital accumulation is possible through the continued exploitation of society and its people, as well as the environment. This means that the imperative of accumulation and economic growth leads to continued destruction of both the environment and the social fabric. Hence, to prevent current and future destruction, capital accumulation and economic growth must be brought to a halt. However, within capitalism this would lead to systemic crises, as the system relies on the continuation of economic growth (i.e. further capital accumulation possibilities). This makes clear that degrowth is incompatible with capitalism and its modus operandi (Foster 2011; Kallis, Demaria and D’Alisa 2015; Liodakis 2018). Yet it also indicates that degrowth signifies a complete transformation of society to avoid crisis.

Through its aims and definition, degrowth essentially represents a counter-hegemony to capitalist hegemony (see e.g. Buch-Hansen 2018; D’Alisa 2019). Gramsci (1971) describes hegemony as a representation of the dominant structures, ideology, and norms at a certain point in history. Counter-hegemony is the opposition to this hegemony, seeking to overcome and replace it (Fontana 2008). Degrowth as counter-hegemony seeks to overcome capitalism, which has significant implications for economic organisations. At the same time, economic organisations must also align with degrowth counter-hegemony in order to foster this transition.

Gramsci’s (1971) concept of counter-hegemony has found a home in the degrowth discourse, particularly in connection to the state (see D’Alisa and Kallis 2020). However, degrowth scholars have yet to apply these concepts to the study of economic organisations. As mentioned in the introduction, most studies on economic organisations and degrowth (as well as post-growth) disregard capitalism and its political economy. Critique is often solely placed on growth without highlighting the connection to capitalism. This is problematic on two related levels, as explained below.

Firstly, capital accumulation at an organisational level might not lead to economic growth in the organisation itself but enables growth in the wider economic system (van Griethuysen 2010). Hence, the persistent focus only on economic growth at the organisational level in connection to degrowth leaves a blind spot across the systemic dimensions in capitalism. Secondly, the disregard of capitalism and its political economy omits the fact that economic organisations are not only producers of goods but also reproducers of hegemony, and potentially of counter-hegemony. The latter can be achieved by engaging in activities following the common-senses[4] of a counter-hegemony (García López, Velicu and D’Alisa 2017). But these activities alone will not automatically overcome capitalism, as they are often and easily confined to niches (Spash 2020).

To overcome capitalist hegemony, the capitalist superstructure must be replaced (Marx 1867/1969). According to Marx (1867/1969), society’s superstructure represents non-economic structures of society, such as culture and politics. The superstructure maintains and shapes the economic base. Economic structures are represented in the economic base, which in turn shapes and maintains the superstructure and, ultimately, society’s hegemony. Hence, alternative modes of production at the economic base play a key role in shaping society’s superstructure. However, new modes of production do not deterministically lead to a new superstructure and hence hegemony. Rather, alternative modes enable the potential to change the superstructure (Marx1867/1969). Further, a mode of production is a theoretical construct describing a real social condition, albeit in an abstract way. Therefore, a mode of production is not an actor or agent that changes the superstructure. Instead, economic organisations that adopt a particular mode of production can become such agents. This means that economic organisations play a key role in changing society’s superstructure. It is important to point out here that economic organisations are thus in a position between the economic base and superstructure where they are able to shape the superstructure. Yet they are not the agents of the superstructure that maintains and shapes the economic base. In other words, economic organisations are not in a position to change the economic base; rather, they can influence the superstructure to shape changes in the economic base.

Within the capitalist system, economic organisations are forced to operate according to the dominant relations of production. In other words, economic organisations are forced to operate in line with capitalism and its imperative of growth and accumulation. Yet economic organisations can also operate using counter-hegemonic modes of production and organisational forms. This, however, means operating in contradiction to the dominant societal and economic structures. It is vital to understand not only how alternative economic organisations continue to exist despite this contradiction but also how they might influence and transform the superstructure to align with degrowth. The present article operationalises degrowth counter-hegemony as evident in the ways in which economic organisations:

1. deal with the above contradiction of an alternative mode of production/organisation within capitalist economic and social structures

2. potentially influence/transform their surroundings and, ultimately, society’s superstructure

This article also acknowledges that counter-hegemony must be addressed at the level of production itself. However, it is our belief that CBPP (i.e. the mode of production) is theoretically closely aligned to degrowth in terms of the parameters of the mode of production (see Kostakis et al. 2018; Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova 2020), which is why CBPP has been dubbed a natural ally to degrowth (see Kallis 2018). This alignment is currently based on thin theoretical and empirical foundations. However, for the purposes of this article, our starting point sees CBPP (as a mode of production) as well suited for degrowth at a production level. Therefore, the operationalisation of degrowth within the above two points makes it possible to focus on the political economic alignment at the organisational level of CBPP: that is, focusing on economic organisations using CBPP (that is, CBPP organisations) and the ways in which these align with degrowth counter-hegemony.

2.2.

Commons-Based Peer

Production

Since the broad introduction of the Internet, and consequently digital commons, CBPP has emerged as a new mode of production and organisation (Benkler 2007). It is exemplified through Free and Open Source Software and Wikipedia, but also open hardware projects such as the RepRap 3D printer. As the name suggests, CBPP is a commons-based ‘variant’ of peer production (PP). Benkler (2007) describes PP as a way to organise production/innovation in a peer-to-peer (P2P) way without the need for centralised control or market incentives. PP builds on P2P coordination to enable self-identified contributions from loosely affiliated individuals or groups with no predefined roles or structure.

The difference between PP and CBPP lies in the property rights on the means of production, as well as the outcomes created (Benkler 2017). Within CBPP both property rights on the means of production and the outcomes produced are freely shared as commons through licences such as the GNU General Public Licence or Creative Commons licensing (Bauwens and Kostakis 2014). PP, on the other hand, does not prescribe the need to adopt this commons perspective. Benkler (2017) argues that PP can be used as a tool within firms to create new innovations and retain these through property rights such as patents. In other words, PP can serve firms’ capitalist-defined goals for innovation, accumulation and growth (Pansera and Fressoli 2020; van Griethuysen 2010). Contrastingly, CBPP employs commoning (Bollier and Helfrich 2015; 2019), that is, the capacity to contribute to and benefit from the commons, based on community-defined rules and norms. Commoning can resist capital accumulation, thus transfusing CBPP with a counter-hegemonic affinity that has been connected to degrowth (see Kostakis et al. 2018).

Kostakis et al. (2018) argue that CBPP is a potential mode of production for degrowth because it enables production and innovation without being primarily driven by profit maximisation. One configuration of CBPP that builds on the conjunction of a global knowledge commons with local distributed manufacturing capabilities exemplifies its potential for material production. This configuration, codified as ‘design global, manufacture local’ (DGML) is documented in a broad array of practices and artefacts, from small-scale wind turbines and prosthetics (Kostakis et al. 2018; 2015), to farming tools (Giotitsas 2019) and even buildings (Priavolou and Niaros 2019).

Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova (2020) explore the connection between degrowth and CBPP further by arguing that CBPP organisations must adopt the aim of eco-sufficiency to fulfil the degrowth aspects of a focus on needs and conviviality (see also Pantazis and Meyer 2020). Within these links, the ambivalence between the political economy of capitalism and the potential for CBPP to assist degrowth as a counter-hegemony remains largely unaddressed. Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova (2020), for example, argue that an adoption of eco-sufficiency within CBPP organisations seems unlikely and risky in the context of capitalism, as this adoption would require forgoing potential profits with the relevant impacts on their economic viability. However, research around the contradictions of a potentially counter-hegemonic mode of production in capitalism at the organisational level is still lacking.

CBPP has been connected to political economy and its potential as an alternative mode of production (see e.g. Bauwens 2005; Bauwens, Kostakis and Pazaitis 2019). Rifkin (2014) argues that this mode of production could replace the capitalist mode of production but sees it as a rather deterministic emergence in which capitalism would be pushed into a niche. CBPP constitutes an alternative, but how this mode is to overcome capitalist hegemony seems unclear. As mentioned in Section 2.1., economic organisations can be viewed as agents using a particular mode of production (in this case, CBPP organisations), which therefore have a role in influencing and shaping the superstructure so that it begins to maintain a different economic base and mode of production. Yet organising in line with an alternative mode of production entails operating in contradiction to dominant economic processes enforced through the hegemonic superstructure (Bauwens, Kostakis and Pazaitis 2019).

If CBPP is a mode of production that can be aligned with degrowth counter-hegemony, it becomes essential to understand how economic organisations operating using CBPP (i.e. CBPP organisations) deal with the resulting contradiction, while also shaping a new superstructure to help overcome this contradiction. For degrowth counter-hegemony, an organisational theory that enables the understanding of an economic organisation within the complexity of society is required.

2.3.

Observing Organisations

as Social Systems

Seidl and Becker (2006) argue that Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory is an often overlooked approach that can help in understanding organisations as complex social systems in the wider context of society. The lack of uptake of social systems theory may stem from the complexity and abstractness of the theory itself, but also from the previous lack of translation of Luhmann’s work. However, in recent years, many of Luhmann’s core works have finally been translated from German to English, broadening the theory’s international reach (see e.g. Luhmann 2012; 2018; 2017).

Luhmann (2012) conceptualises different forms of social systems (such as organisations and sub-systems) that together form society (in itself a social system) as a whole. All social systems consist of communication as their elements and reproduce themselves through this communication (Schuldt 2006). In social systems theory, communication consists of three elements that create the unit of communication: utterance, information, and understanding (Luhmann 2018). According to Luhmann (2012), communication can either be accepted or rejected, making it uncertain whether communication will lead to further communication. As social systems require continued communication for their reproduction, this fact also makes the reproduction of social systems uncertain (Seidl 2018; Seidl and Becker 2006). Social systems therefore create internal structures and processes that are more likely to result in the acceptance of communication. Social systems draw a distinction between themselves and their system environment to make their reproduction more likely (Luhmann 2006). They must constantly observe their system environment and decide how to react to or ignore communication by other social systems. Beyond their own internal structures, social systems create structural couplings with their system environment to reduce the uncertainty of the sheer amount of complexity and possibility the system environment represents (Lippuner 2011; Seidl 2018). Ultimately, social systems create structures to reduce complexity (Luhmann 2006).

Luhmann (2018) conceptualises organisations as a unique form of social system. Organisations have a particular form of communication, decision communication, which means that decisions themselves are “a specific form of communication” (Seidl and Becker 2006, 26). Decisions become the foundation for future decisions, leading to the possibility of coordinating actors and actions on a grand scale (Simon 2013). Decision communication, like any communication, must lead to further communication to make the reproduction of the system more likely. Organisations constantly communicate their decisions in the form of structures, processes, and rules. An organisation as a social system has to endlessly reproduce the communication of decisions to maintain its distinction from its system environment (Seidl and Becker 2006). Decisions and the resulting decision communication take place on the back of previous decisions, that is, decision premises (Besio and Pronzini 2010; Luhmann 2018). Decision premises constitute previous decisions that provide the reference for present decisions to be made (Seidl and Becker 2006). This means that decision premises help to enable further decision communication and hence the organisation’s systemic reproduction.

This article uses Luhmann’s (2018) social systems theory on organisations as an analytical tool to study economic organisations. The empirical focus is on the organisations’ decision premises (see Besio and Pronzini 2010). There are five types of decision premises (see Seidl and Becker 2006):

1. Programmes → criteria on how to decide, e.g. processes/process maps

2. Personnel (recruitment and assignment rules) → expected decisions new personnel will ‘make’

3. Communication channels → organisation of the organisation, e.g. internal hierarchy

4. Organisational culture → handling of the decision-making process in the organisation

5. Cognitive routine → conceptualisation of the organisation’s system environment

Seidl (2018) argues that beyond decision premises a further key factor of organisational systems is their self-description; that is, how the organisational social system describes and observes itself. An organisation often has various potentially opposing self-descriptions. For example, the accounting department of a firm might describe the organisation differently to the way the sales department would. Self-descriptions strongly influence decision premises and can thus sometimes act as decision premises themselves (Seidl 2018). This article uses the above five decision premises, as well as self-description as an analytical tool, to observe organisations. In the context of degrowth, this means analysing how the five organisational decision premises plus self-description in CBPP organisations might align with degrowth counter-hegemony as operationalised at the end of Section 2.1.

3.

Method

This study adopted a qualitative case study approach in order to investigate CBPP organisations in depth. Case study research can be conducted in multiple ways. Though single case study research can reap insightful findings, the present study chose to use a multi-case study approach to allow for potential comparisons between cases (Vincent and Wapshott 2014; Yin 2003).

The case selection followed the criteria of finding economic organisations with CBPP as their mode of production. The first author’s network of CBPP practitioners was tapped into, and snowballing was used to find suitable cases willing to participate in the study. Two cases emerged: Wind Empowerment, a CBPP network enabling its members to create and share knowledge of small-scale wind turbine production; and P2P Lab, a research collective focusing on the commons.

CBPP is an emerging phenomenon that is difficult to isolate from its context (Bauwens, Kostakis and Pazaitis 2019). Taking this into account, the authors have adopted a case study approach inspired by participatory case study research to enhance the understanding of both the underlying processes and the contextual setting of the two cases (Reilly 2010).

There are multiple means of data collection for case study research (Robson 2011; Yin 2003). Semi-structured in-depth interviews (Fiss 2009) were conducted as the main data collection method. Snowballing (see Biernacki and Waldorf 1981) was used to increase the number of interviewees. Interviews were structured to touch upon the decision premises and self-description of the organisation. Interview length ranged from 40 to 100 minutes. Skype was used to conduct and record the interviews. All interviews were transcribed to allow for easier analysis. In total 11 and 9 interviews were conducted with members from Wind Empowerment and P2P Lab respectively.

In the case of Wind Empowerment, four board and strategy meetings were observed; field notes were created for analysis from these observations. As the meetings within P2P Lab are held in Greek, observation was not possible. Wind Empowerment provided three key strategic documents (Charter, Constitution, and Finance and Procurement Policy) for document analysis (see Coffey 2013). Wind Empowerment also provided access to an email conversation which was deemed relevant to the research after initial conversations. These emails were analysed as documents. Due to their modus operandi, P2P Lab does not have similar strategic documents available for analysis. Instead, its members referred to the academic research publications of the collective. These publications were not analysed in the same way as the rest of the data (as outlined below). Rather, the publications were used as academic references to enrich the study’s findings.

Regarding the participatory aspect of the study, the second author is a core member of P2P Lab, which, as mentioned above, is a research organisation dedicated to the documentation of the CBPP phenomenon. For this reason, the initial discussions that took place in the context of the interviews within the case of P2P Lab led to broader insights for the investigation of the topic itself. It was thus deemed beneficial to the research outcome to adopt a more participatory approach.

The third author is an executive board member of Wind Empowerment. Through this approach, the present article includes the expertise of both studied cases in the assimilation of the collected data.

To balance any confirmation bias or potential conflicts with preconceived notions, the second and third authors were only involved in the analysis and discussion phase of the research, while the first author provided critical checks and had the final say in the key decisions concerning the research process. Data was collected solely by the first author, while the other authors were given access only to fully anonymised data.

The collected data was anonymised and imported into NVivo for analysis. The analysis followed the general technique of coding (see Roulston 2013). However, instead of identifying recurring themes to code the data by, the earlier mentioned five decision premises and self-description (see Section 2.3.) were used as themes to code. The coded data was then analysed using the two key points of degrowth counter-hegemony as operationalised in Section 2.1.

4.

Findings

The findings derive directly from the analysis of the various collected data described in Section 3. In the following, the findings for each case organisation are structured around the themes of self-description and the aforementioned five decision premises (see Section 2.3.) as well as degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment (as operationalised in Section 2.1.). The findings for Wind Empowerment and P2P Lab are described in Section 4.1. and Section 4.2. respectively. Comparisons are drawn in Section 4.3.

4.1.

Wind Empowerment

Wind Empowerment (WE) is a global CBPP network for the development of locally manufactured small wind turbines for sustainable rural electrification. The membership consists of 73 organisations in 43 countries, spanning almost all continents, ranging from organisations such as cooperatives and enterprises to NGOs and university research groups. WE seeks to develop and share knowledge concerning the manufacture and maintenance of small-scale wind turbines. Through this, WE aims to empower its members in achieving its goal of sustainable rural electrification.

The findings and data analysis for WE are shown in Table 1 below. The table presents the findings (left column) and analysis (right column) for WE’s self-description and each of the five decision premises separately. The findings derive directly from the collected data as set out in Section 3. The analysis of the data derives directly from the investigation of the findings’ counter-hegemonic degrowth alignment as set out at the end of Section 2.1.

|

Self-description |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● WE is a network of various organisations and institutions coming together under the topic of small wind and sustainable rural electrification. ● Charitable non-profit organisation. ● Member-driven organisation. ● Interpretation of role and purpose of network dependent on individual members’ interpretations. Reliant on decision premise personnel. ● Self-description is strongly connected to decision premise programmes. |

● WE’s self-description is too broad and vague to be interpreted as aligned with degrowth counter-hegemony. ● Self-description is reliant on the counter-hegemonic alignment of the decision premises programmes and personnel. |

|

Programmes |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● WE’s goal is to help with the development of locally manufactured wind turbines for rural electrification. ● WE aims to achieve its goal by enabling its members through collaboration as well as open-source knowledge and technology sharing. ● WE’s activity must align with the goal and aims of the organisation. ● Documentation of goals and aims is seen as a guide for executive board members in decision-making. ● Discussions are held around opposing interpretations of how to achieve WE’s goals. ● Ultimately, the interpretation of the goals and mission is left to the members. ● Programmes is reliant on decision premise personnel. |

● WE’s decision premise of programmes can potentially fit within a degrowth system. The aim of freely sharing knowledge and technology fit in particular. ● Lack of alignment with degrowth counter-hegemony. ● Discussions around interpretation of WE’s goals could lead to a more concrete and potentially counter-hegemonic decision premise. ● Programmes is reliant on the counter-hegemonic alignment of decision premise personnel. |

|

Personnel |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● Organisations, institutions, and individuals can become members of the network if involved in small wind and aligning with the WE’s mission and guiding principles. ● Executive Board members are voted into their position in theory, but are essentially selected for the fact of putting themselves forward, rather than which decisions they will make. ● Executive Board members are trusted to act in line with WE’s mission and guiding principles. ● Personnel is reliant on self-description and programmes. |

● Very loose definition of personnel that shows no direct alignment with degrowth counter-hegemony. ● Personnel is reliant on counter-hegemonic alignment of self-description and programmes. As stated above, these are also reliant on personnel for their counter-hegemonic alignment. |

|

Communication channels |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● All members can participate in discussions of the executive board (forum or meetings). ● Executive board members make the majority of small-scale decisions by referring to programmes and self-description. ● Controversial and large-scale decisions are voted on by not-for-profit members (due to WE’s charity status). ● Communication channels is reliant on personnel decision premise and ultimately the members’ individual interpretations of WE’s self-description and programmes. |

● Counter-hegemonic potential in only not-for-profit members being able to vote. However, this does not represent a counter-hegemonic alignment overall. ● Communication channels is reliant on counter-hegemonic alignment of personnel, and through this, programmes, and self-description. |

|

Organisational culture |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● Both decision premises, self-description and programmes, are used and referred to in discussions. ● Emphasis on reaching consensus in decisions to avoid the need to vote. ● Organisational culture is reliant on executive board members and other members to refer to and interpret the organisational mission and aims. ● Organisational culture is reliant on decision premise personnel and the interpretation of other decision premises by its members. |

● No clear alignment with degrowth counter-hegemony. ● Organisational culture is heavily reliant on the counter-hegemonic alignment of decision premise personnel and how other decision premises (programmes and self-description) are interpreted by members. |

|

Cognitive routine |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● Main conceptualisation of the system environment is at the ecological level. ● Awareness of planetary boundaries and need for sustainable resource management. ● Lack of conceptualisation of the social system environment, i.e. the capitalist system. WE’s CBPP mode of production is not perceived as being in contradiction to capitalism. ● WE situates itself as neutral to the capitalist system. The network does not aim to accumulate. Member organisations can use the network for accumulation purposes. ● Cognitive routine is reliant on the perception of individual members. |

● Lack of awareness of CBPP in contradiction to the capitalist modus operandi. ● Instead of dealing with the contradiction of CBPP as an alternative mode of production within the capitalist system, WE distances itself from the problem and lets every individual member autonomously deal with this contradiction. ● WE’s neutral stance represents a lack of counter-hegemonic alignment in the decision premise. ● Cognitive routine is reliant on counter-hegemony alignment of personnel decision premise. |

Table 1: Findings and data analysis for Wind Empowerment

All decision premises, including self-description, can be observed within WE. The core decision premises (i.e. the decision premises the organisation most relies on) for WE are personnel, programmes, and self-description. These three decision premises are heavily reliant on and influence each other. In other words, these three decision premises use each other as decision premises. WE’s self-description and programmes are relatively broad and vague, which means that they can be used as a guide, but that ultimately the interpretations of these two decision premises in specific situations depends on an individual member’s (particularly an executive board member’s) interpretation. For example, one of the main programmes within WE is its charter document. All of WE’s activity needs to align with this charter. Within WE’s charter is a process that describes what to do in the executive board in case of a controversial decision. However, apart from project collaborations with large for-profit entities, the document does not define controversial decisions. One interviewee in particular stated that “[t]he understanding of each person of what is controversial and what is not is different. So that is where we need to be more specific”.

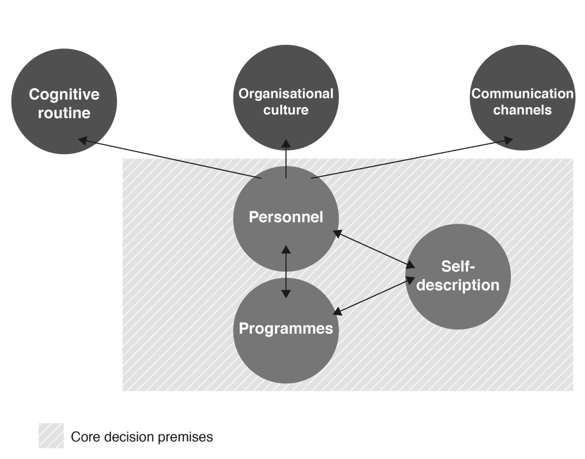

If identified as a controversial decision, the decision in question is opened to the whole voting membership. Non-controversial decisions will only be taken to a vote if consensus cannot be reached. This further emphasises the reliance on the individual member’s interpretation of programmes and self-description. WE is therefore heavily reliant on the decision premise personnel. WE’s three remaining non-core decision premises (communication channels, cognitive routine and organisational culture) are also heavily reliant on the decision premise personnel and consequently the interpretation of the other two core decision premises through specific members. This is graphically highlighted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Wind Empowerment’s decision premises and their interconnection

Similarly to programmes and self-description, personnel as a decision premise is kept relatively vague. New members can join WE as long as they are active within small wind and align with WE’s mission and guiding principles. Further, executive board members (which are usually members of WE’s member organisations) are elected by WE’s membership. However, one interviewee in particular was adamant in pointing out that:

[P]eople just vote for anybody who's been suggested, who’s applied for the board. And because of this, I don’t think people actually think much about who they vote for. Personally, I don’t really agree with this, I don’t really like this much, because I think that if we actually did pay attention to this as a network we would have a better board, we would have potentially done more things, but this is just a guess.

This highlights that the decision premise personnel (that is, the expectation of how a person will act/decide) is very weakly defined. Yet all other decision premises are heavily reliant on or influenced by this decision premise. This has further stark implications for the degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment of WE.

The three core decision premises (as shown in Figure 1) are reliant on and influence each other regarding counter-hegemonic degrowth alignment. Further, the three non-core decision premises are reliant on the counter-hegemonic alignment of personnel and, again, the consequent interpretation of the other core decision premises. However, due to the vagueness and broadness within the core decision premises, a degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment on the whole cannot be observed. Therefore, WE lacks an overall awareness at the organisational level regarding the contradiction of CBPP as a mode of production within capitalist hegemony. Consequently, WE has no definite way of dealing with this contradiction. Essentially, individual member organisations have to decide themselves how to survive within the capitalist system. For various member organisations this results in following the imperatives of capitalism (i.e. accumulation and profit-making) to survive. In relation to this, one interviewee stated that “Wind Empowerment tries to position itself as an A-capitalist[5] institution, but it’s besieged by capitalist imperatives of its members; but still it is trying to hold strong and not position itself as a capitalist institution”.

Any counter-hegemonic alignment is reliant on individual members and their own potentially counter-hegemonic interpretation of the decision premises. However, the lack of counter-hegemonic alignment of personnel fails to ensure counter-hegemony throughout the other decision premises. In other words, WE does not ensure the reproduction of degrowth counter-hegemony through its decision premises. WE’s alignment with degrowth is limited to the mode of production, namely CBPP. The aforementioned collaborations with for-profit entities arguably pose the risk of co-optation of CBPP, as we discuss in Section 5. Further organisational alignment at the level of political economy through its decision premises would be required to mitigate this threat.

4.2.

P2P Lab

P2P Lab is an interdisciplinary research collective focusing on the commons. Its members conduct research to explore and document CBPP, while putting this knowledge of the phenomenon into practice through participatory research methods with the communities engaged, but also in P2P Lab operations. Hence, P2P Lab members employ CBPP practices to write, edit and publish articles, reports and books on a diverse range of relevant topics, and further organise community-oriented events for reflection, action and education, while comprising a CBPP community themselves.

The findings and data analysis for P2P Lab are shown in Table 2 below. The table presents the findings (left column) and analysis (right column) for P2P Lab’s self-description and each of the five decision premises separately. The findings derive directly from the collected data as set out in Section 3. The analysis of the data derives directly from the investigation of the findings’ counter-hegemonic degrowth alignment as set out at the end of Section 2.1.

|

Self-description |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● A research collective studying CBPP while also participating in related practises. ● Described as having an activist nature and motivation. ● Different self-descriptions (internal and external). ● External self-description with varying degrees of radicality and adaptable vocabulary to help in receiving funding. ● Commons-based organisation within a non-commons-based system. Awareness of its system environment in self-description. ● Reliant on decision premise cognitive routine as well as programmes. ● Influences the decision premise of personnel. |

● Self-description hints at awareness of the contradiction of CBPP in the capitalist system. This represents a degree of counter-hegemonic alignment with degrowth. ● This awareness of the contradiction influences the use of different self-descriptions. ● Self-description influences and relies on the counter-hegemonic alignment of programmes, personnel, and cognitive routine. |

|

Programmes |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● P2P Lab’s goal is to research the commons and CBPP to enable CBPP as the main mode of production. ● P2P Lab aims to influence societal change through change in mode of production and organisation. ● All projects must align with the overall aim of P2P Lab. ● Aims are not recorded and are highly reliant on members to embody them. ● Programmes is connected to self-description. ● Programmes is reliant on decision premise personnel. ● Programmes is connected to cognitive routine in awareness to change the societal system. |

● The goal to enable CBPP as the main mode of production is in clear opposition to the capitalist hegemony and its mode of production. This is a strong alignment with the operationalisation of degrowth counter-hegemony as defined in Section 2.1. ● Programmes influences and relies on the counter-hegemony of cognitive routine, self-description and personnel. |

|

Personnel |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● Members are trusted to act in accordance with P2P Lab’s goals and values. Through this trust, members can act autonomously. ● New members are invited because of overlapping worldviews and values. Essentially, new members must roughly align with the interpretation of other decision premises. ● Personnel relies on and influences decision premises programmes, cognitive routine and self-description. |

● By selecting new members in accordance with the decision premises of programmes, cognitive routine and self-description, the counter-hegemonic alignment of these decision premises also aligns personnel to the same extent. ● The reliance on personnel and its counter-hegemony by the other decision premises helps to reinforce counter-hegemony in both directions. |

|

Communication channels |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● P2P Lab is structured in a heterarchical way. ● Members as coordinators have autonomy to make decisions to fulfil their projects. ● P2P Lab trusts its members to act in accordance with the organisation's vision and aims. ● Communication channels is reliant on decision premise personnel. |

● Degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment not explicitly evident in communication channels. ● Communication channels is reliant on counter-hegemonic alignment of decision premise personnel. Through personnel, also reliant on self-description, programmes, and cognitive routine. |

|

Organisational culture |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● Flexible with the decision premise of programmes. P2P Lab participates in projects that do not fully align with its values and aims to ‘hack’ them and better align them. ● Trusts its members to stay true to the values and aims of the organisation. ● Organisational culture is reliant on decision premise personnel and programmes. ● Organisational culture is reliant on decision premise cognitive routine to identify need and possibility to ‘hack’ projects. |

● Counter-hegemonic alignment and awareness that the system environment is likely not aligned with P2P Lab’s vision. ● Influences its system environment to become more counter-hegemonic by ‘hacking’ projects. ● Organisational culture is reliant on counter-hegemonic alignment of programmes, personnel and cognitive routine. |

|

Cognitive routine |

|

|

Findings |

Analysis – Degrowth

counter-hegemony alignment |

|

● Awareness of the contradiction that CBPP as a mode of production clashes with the capitalist system. ● Awareness that P2P Lab cannot leave the system of capitalism and compromises must be made to survive with this contradiction. ● Perception of capitalism as destructive and problematic for society and environment. ● P2P Lab communicates its values into the system environment to influence change. ● Cognitive routine relies on and influences self-description, programmes, and personnel. ● Cognitive routine heavily influences the decision premise of organisational culture. |

● Aligns with degrowth counter-hegemony through a strong awareness of the contradiction of CBPP being an alternative mode of production. ● Recognises the need to overcome the capitalist system. ● Actively tries to influence its system environment to align with degrowth counter-hegemony. ● Cognitive routine is reliant on and influences counter-hegemonic alignment of self-description, programmes, and personnel. ● Cognitive routine heavily influences the counter-hegemonic alignment of organisational culture. |

Table 2: Findings and data analysis for P2P Lab

Within P2P Lab all decision premises, including self-description, are observable. P2P Lab has four core decision premises that are heavily reliant on and influence each other. These are self-description, programmes, cognitive routine and personnel. The four core decision premises together reinforce each other to work towards P2P Lab’s mission in line with its organisational values. One interviewee explained the overall aim of the organisation as follows:

[…] to try to steer the digital revolution and the modes of production yet to come towards a commons-based perspective. So, our dream, if you will, would be that the capitalist mode of production, the industrial-capitalistic and liberal mode of imaginaries and ways of doing stuff in our societies, could be transcended if a lot of people and subjects work towards this direction into a better society, into a system whose characteristics would be increasingly different from the value driven and profit driven ones that we have now.

The aim to help shape the societal system that lies beyond the organisational system itself hints at a strongly defined cognitive routine to influence the organisation’s programmes and self-description, and vice versa. The cognitive routine of P2P Lab helps the collective to understand that its mode of production (CBPP) is not aligned with the capitalist system and that it needs to ‘hack’ parts of the system in order to be able to survive. One interviewee stated: “What we usually do is try to hack/modify some parts of the projects and get the best out of them with regard to what we want to achieve”.

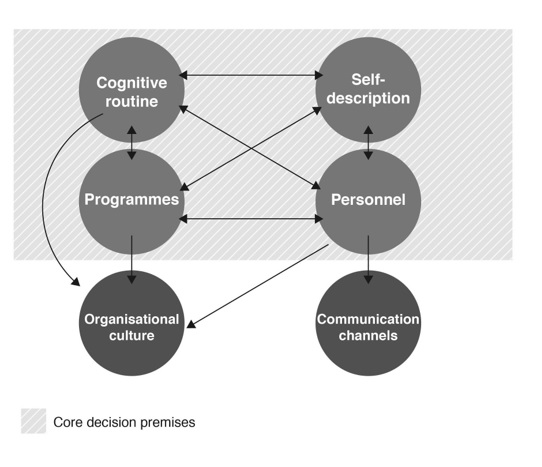

P2P Lab’s cognitive routine is highly important in order for it to be able to follow its programmes and self-description. However, the programmes and self-description of P2P Lab are not documented; rather, they are embodied and lived by its members. This highlights a strong reliance on the members of the organisation and ultimately the decision premise personnel. New members must align with P2P Lab’s aims and goals, but also broadly share its worldview and conceptualisation of its system environment. Through its decision premise personnel, P2P Lab reinforces the other three core decision premises. Therefore all four core decision premises influence and reinforce each other. The remaining two decision premises (communication channels and organisational culture) are influenced by core decision premises. This is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: P2P Lab’s decision premises and their interconnection

Within P2P Lab, the four core decision premises reinforce each other in terms of degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment. Within self-description, programmes and cognitive routine, this alignment can be observed in the fact that P2P Lab shows awareness of its mode of production (CBPP) existing in contradiction to the capitalist system. P2P Lab aims to enable CBPP to become the main mode of production, which would ultimately mean overcoming capitalism. The organisation actively tries to influence its system environment by ‘hacking’ projects and constantly communicating its values. Further, P2P Lab uses various self-descriptions, depending on its audience, to receive funds and enable transfers of value from the capitalist system towards commons-based initiatives, a process referred to as transvestment.[6] One interviewee described this process:

Transvestment means you transfer value from one modality to the other. So, we're trying to basically create strategies that transfer resources, that is financial resources, people skills, capacities, assets, buildings, whatever, from the capitalist mode of production to the commons-based one.

The decision premise of personnel helps to ensure that only new members whose personal values and worldview broadly overlap with this counter-hegemonic alignment become members of the organisation. The two non-core decision premises are reliant on the counter-hegemonic alignment of the core decision premises they are connected to (as highlighted in Figure 2). The decision premise of cognitive routine arguably plays a significant role in the degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment of P2P Lab. It emphasises the awareness and conceptualisation of the organisation’s system environment. This does not mean that the cognitive routine alone enables counter-hegemonic alignment, but rather that it enables it in conjunction with the other three core decision premises, reinforcing each other in counter-hegemonic terms. It must also be highlighted that P2P Lab does not explicitly aim to achieve a degrowth society. P2P Lab shows counter-hegemonic alignment with degrowth, without labelling it as such.

4.3.

Summary and Comparison

All decision premises and self-description are observed in both cases. Both cases make autopoietic sense to themselves. That is, both organisations, their decision premises, self-description, and resulting modus operandi make sense within and to the respective organisational social system and their self-reproduction. Overall, neither case explicitly aims to achieve or align with degrowth. Yet degrowth alignment can be observed within both cases, albeit to varying extents.

Within P2P Lab there is a clear vision to change and transform society. The organisation acknowledges that it is politically motivated and aims to find and nurture possibilities to transcend capitalism. P2P Lab has an explicit awareness of its capitalist system environment and the entailed contradiction of using CBPP as a mode of production within the capitalist system. This awareness is evident throughout the organisation’s core decision premises. Through this awareness, P2P Lab is able to deal with the contradiction of CBPP in a capitalist system (for example, by engaging in transvestment from the capitalist system to the commons-based system by using different self-descriptions) but also to influence its system environment in efforts to ‘hack’ and modify other projects. Therefore, P2P Lab can arguably be seen as aligned with degrowth counter-hegemony as outlined in Section 2.1. P2P Lab achieves this alignment through ensuring membership that aligns with its worldview and goals. In other words, P2P Lab strongly relies on its decision premise personnel to ensure this alignment. This results in a relatively small membership, which in turn might also help to ensure the alignment. This reliance on personnel is further emphasised by the fact that P2P Lab’s aims and goals are not explicitly recorded. Decision premises do not need to be documented as such to exist within the organisation (see Seidl 2018). In other words, the documentation of decision premises does not ensure their concreteness.

WE is most concerned about sustainable energy access as a basic human right. WE tries to achieve positive social and environmental change without necessarily associating capitalism as the root cause of the problem the organisation tries to address. This might explain why WE shows a lack of awareness of, or ignores, the contradiction that CBPP creates within a capitalist system. Similar to P2P Lab, WE relies on its members to align with the organisation’s goals and mission. Yet WE’s decision premises are too vague and broad to be considered as aligned with degrowth counter-hegemony. Further, WE’s goals and aims, in contrast to P2P Lab, are well documented. That is not to say that the documentation of these decision premises leads to the aforementioned vagueness. WE has the potential to concretise its documented decision premises. The fact that WE has started to document certain things more explicitly is proof of that potential.

The decision premise of personnel is similarly vague and ‘only’ ensures that WE creates an affinity group around the topic of small-scale wind turbines, with an emphasis on open knowledge-sharing. This could be the reason for a larger membership in comparison to P2P Lab, as it is easier to organise around this affinity. Yet, simultaneously, this means that a counter-hegemonic degrowth alignment cannot be assured through the decision premise personnel. Hence, WE lacks a clear alignment with degrowth counter-hegemony as operationalised in Section 2.1. However, WE is able to create a much larger membership around the use of CBPP as a potentially counter-hegemonic mode of production. Consequently, WE enables counter-hegemonic activity through the use of this mode of production on a larger scale than P2P Lab, but lacks alignment on a stronger political economic level. However, enabling potential counter-hegemonic activity through this looser alignment also spells the risk of capitalist co-optation. In the case of WE, collaborations with large-scale for-profit entities precisely represent such a potential for co-optation. In other words, the larger-scale engagement with CBPP (which is not guaranteed to be counter-hegemonically aligned) simultaneously comes with the higher risk of co-optation and potentially hindering degrowth counter-hegemony.

5.

Discussion and

Concluding Remarks

As mentioned earlier, CBPP has previously been linked to degrowth (Kostakis et al. 2018; Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova 2020). Similarly, Kallis (2018) describes CBPP as a “natural ally” to degrowth. However, this does not signify an overall alignment with degrowth. Indeed, Kostakis (2018) argues that digital commons (and thus, consequently, CBPP) do not automatically lead to a more sustainable society beyond capitalism, but heavily depend on how and for what these phenomena are used. Kohtala (2017) problematises the lack of concrete sustainability conceptualisations in maker and P2P communities. Robra, Heikkurinen and Nesterova (2020) emphasise that CBPP organisations must actively aim to align with degrowth through eco-sufficiency. The findings of this article echo and add to these insights by highlighting that a political economic alignment with degrowth is not achieved simply through the use of an alternative mode of production.

Our research question was: Do commons-based peer production organisations demonstrate counter-hegemonic degrowth in their decision premises? If so, how? The findings show that if CBPP organisations align with degrowth counter-hegemony on an organisational level within their decision premises, they do so through a strong awareness of the contradiction of CBPP as an alternative mode of production that must tame and erode, and transcend, capitalist hegemony, to build on the late Erik Olin Wright’s (2015) phrasing.

It is an important insight for the quest of achieving a degrowth society that economic organisations such as CBPP must develop beyond ‘natural allies’ and align with degrowth counter-hegemony at an organisational level. This insight has significant implications for these organisations. The case of P2P Lab shows that a strong awareness of the contradiction of CBPP in the capitalist system and the aim to influence a shift in societal structures helps to survive this contradiction and align with degrowth counter-hegemony simultaneously (albeit implicitly). However, this is only achievable through explicit membership alignment to the values reflecting this counter-hegemony, which results in and is ensured through the relatively small membership and size of the organisation.

It is tempting to draw the conclusion that degrowth must focus on small economic organisations that can more easily be aligned with degrowth. Nesterova (2021; 2020) similarly argues that small economic organisations are better equipped to fit a degrowth society. However, in light of the findings in this article, this issue might be more nuanced than just a question of large or small scale. WE achieves a wider engagement with CBPP and the potential of counter-hegemonic activity through its larger size. P2P Lab (at least on its own) cannot achieve this due to its size. Through its broader and vaguer aims and personnel decision premise, WE manages to create a network with a large number of members around CBPP as an alternative mode of production. CBPP can arguably be seen as a mode of production fitting degrowth counter-hegemony. This counter-hegemonic potential does not lead to an automatic alignment at the organisational level. However, the engagement with CBPP as a mode of production has the potential to lead to counter-hegemonic activity in general.

Counter-hegemonic activity might not represent a counter-hegemonic alignment with degrowth at the organisational level, but it is essential to help overcome capitalist hegemony. Counter-hegemonic activity generally highlights how things can be done differently to the dominant hegemony (Kallis 2018; García López, Velicu and D’Alisa 2017; Pansera and Owen 2018). Counter-hegemonic activity around CBPP enables wider adaptation of this mode of production, which is arguably desirable in order to achieve a degrowth society. This means vaguer degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment (as in WE) enables the wider acceptance of CBPP as an alternative mode of production.

However, as mentioned earlier, the vaguer degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment comes with a much higher risk of capitalist co-optation. WE’s alignment with degrowth is solely on the level of its mode of production, i.e. CBPP, by incorporating technological openness and non-growth/non-profit orientation through its self-description and programmes. These elements, as argued in Section 2.2, make CBPP a fitting mode of production for degrowth counter-hegemony. Yet CBPP and CBPP organisations emerge in the context of capitalist structures at the economic base as well as the superstructure. That means CBPP (and CBPP organisations) can and are increasingly co-opted by capitalist economic organisations. Indeed, it has been extensively documented (see e.g. Birkinbine 2020; Lund and Zuckerfeld 2020; Pazaitis and Kostakis 2021) that the digital commons and commons-based economic relations have always been exploited to fulfil capitalist imperatives; a condition that has only expanded in the emergence of the digital economy.

To re-emphasise, CBPP and its economic organisations may be compatible – but are not automatically aligned with degrowth counter-hegemony. Deploying CBPP does not necessarily translate to a degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment at the organisational level, that is, through alignment of decision premises. The counter-hegemonic potential of CBPP lies in leveraging opportunities of commons-based relations (i.e. through CBPP organisations) to influence the superstructure. The superstructure is then in a position to change the economic base to further enable CBPP. Cases such as P2P Lab and WE demonstrate how CBPP patterns can be translated into different forms of economic organisation. Yet the long-term viability of CBPP organisations simultaneously requires superstructural support to become autonomous and less prone to co-optation.

Various scholars (e.g. Bauwens, Kostakis and Pazaitis 2019; Bauwens and Kostakis 2014; Lund and Zuckerfeld 2020; Pazaitis and Drechsler 2020) have suggested reforms at the economic, legal, technological, or organisational levels, which may be a starting point to mitigate and reverse co-optation. Such suggestions include, but are not limited to, licenses that undermine the use of commons for capitalist purposes as well as new democratic and legal organisation forms. However, these reforms do not represent a superstructural transformation, but still enable CBPP organisations in becoming the agents for this transformational change, re-emphasising the need for counter-hegemonic alignment at the level of CBPP organisations.

In the context of this study’s two cases, it may be stated that the stricter degrowth counter-hegemonic alignment of P2P Lab might be better able to influence a transformation in society’s superstructure. It would be easy to argue that therefore only the strict alignment with degrowth counter-hegemony is beneficial. However, both looser and stricter alignment are required for degrowth as a counter-hegemony to succeed. The latter rationalises commoning as a new ‘common sense’, while the former expands the sphere where commoning and counter-hegemonic activity can take place. Yet the above-presented higher risk of co-optation must be counteracted in this context. Hence, to achieve degrowth, is it a question of finding potential ways to scale up the stricter alignment of P2P Lab to the levels of WE?

The notion of scaling up has been heavily discussed within the scholarly field of CBPP. It has generally been argued that for CBPP to be successful as a mode of production it needs to scale up, as in the case of Internet-based large-scale collaboration (see e.g. Benkler 2007). Yet on a less purely digital but rather digitally-based level,[7] CBPP retained smaller sizes. Particularly in this context, the concept of scaling wide instead of scaling up has emerged (Kostakis and Giotitsas 2020; Kostakis, Giotitsas and Niaros forthcoming). CBPP organisations build networks amongst themselves and learn from and influence each other, essentially forming a CBPP network that is a case of CBPP in itself.

The two studied cases in this article have also co-developed their structures and processes in parallel, forming relations of solidarity and mutual learning. That is, the two organisations have developed through ideas and practices in tandem. Scaling wide through CBPP networks might therefore be a way to help influence further counter-hegemonic degrowth alignment on a larger scale. In future this will mean understanding how smaller (but more counter-hegemonically aligned) economic organisations such as P2P Lab might influence and pollinate larger organisations (such as WE) with more counter-hegemonic ideas and thus represent a counterweight to the increased risk of capitalist co-optation.

From a social systems theory perspective, researching these CBPP networks will entail understanding how economic organisations as social systems will understand and accept communication within such networks. Such networks could arguably be structured to anticipate, understand and accept counter-hegemonic communication. Therefore, there is potential that such networks might increase the likelihood of acceptance for counter-hegemonic communication in a largely hegemonic society.

In conclusion, to fulfil its role in helping to shape and transform society’s superstructure, CBPP organisations need to align their decision premises with degrowth counter-hegemony. However, in order to achieve wider adoption of CBPP as a potentially counter-hegemonic mode of production, a looser alignment might be beneficial. Yet, at the same time, this also bears the risk of further and easier co-optation of CBPP for capitalist purposes. Future research focusing on potential degrowth counter-hegemony alignment within CBPP networks and the concept of scaling wide may unveil useful insights on the trade-offs discussed.

References

Bauwens, Michel. 2005. The Political Economy of Peer Production. CTheory 1. Accessed August 12, 2021. http://www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/~graebe/Texte/Bauwens-06.pdf

Dale, Gareth. 2012. The Growth Paradigm: A Critique. International Socialism 134: 55-88.

Gorz, André. 1994. Capitalism, Socialism, Ecology. London: Verso.

Illich, Ivan. 2001. Tools for Conviviality. London: Marion Boyars.

Kallis, Giorgos. 2018. Degrowth. Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing.

Kostakis, Vasilis. 2018. In Defense of Digital Commoning. Organization 25 (6): 812-818.

Kostakis, Vasilis and Christos Giotitsas. 2020. Intervention – “Small and Local Are Not Only Beautiful; They Can Be Powerful”. Antipode Online. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://antipodeonline.org/2020/04/02/small-and-local/

Latouche, Serge. 2009. Farewell to Growth. Translated by David Macey. Cambridge: Polity.

Liodakis, George. 2018.

Capital,

Economic Growth, and Socio-Ecological Crisis: A Critique of De-Growth.

International Critical

Thought 8

(1): 21. doi:10.1080/21598282.2017.1357487

Lund, Arwid and Mariano

Zukerfeld. 2020. Corporate

Capitalism’s

Use of Openness: Profit for Free? Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Nesterova, Iana. 2020. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121382

Robra, Ben and Pasi Heikkurinen. 2019. Degrowth and the Sustainable Development Goals. In Decent Work and Economic Growth. Encyclopaedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, edited by Walter Leal Filho, A. Azul, L. Brandli, P. Özuyar and T. Wall. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71058-7_37-1

Robra, Ben, Pasi Heikkurinen and Iana Nesterova. 2020. Commons-Based Peer Production for Degrowth? The Case for Eco-Sufficiency in Economic Organisations. Sustainable Futures 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2020.100035

Robson, Colin. 2011. Real World Research [3rd edition]. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Rockström, Johan, Will

Steffen,

Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin III, Eric Lambin, Timothy

Lenton, et

al. 2009. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for

Humanity. Ecology and Society

14 (2).

http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

Schuldt, Christian. 2006. Systemtheorie. Hamburg:

Europäische Verlagsanstalt.

Seidl, David. 2018. Organisational Identity and Self-Transformation. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wright, Erik Olin. 2015. How to Be an Anticapitalist Today. Jacobin Magazine, December 2. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://jacobinmag.com/2015/12/erik-olin-wright-real-utopias-anticapitalism-democracy

About the Authors

Ben

Robra

Ben Robra is a PhD researcher at the Sustainable Research Institute at the University of Leeds. His research focuses on economic organisations in connection to Degrowth. Other research interests include commons-based peer production, digital commons, political economy and social systems theory.

Alex

Pazaitis

Alex Pazaitis is a core member of P2P Lab, an interdisciplinary research collective and spin-off from the Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology and of the P2P Foundation. He holds a PhD in Technology Governance and is Researcher at the Ragnar Nurkse Department. His research interests include technology governance, innovation policy, digital commons, open cooperativism and distributed ledger technologies.

Kostas

Latoufis

Kostas Latoufis is a researcher at the SmartRUE research group of the Electric Power Division of the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA). His work focuses on locally built small wind and pico-hydro systems used for rural energy access. Kostas is currently a PhD candidate at the Fluids Division of the NTUA. He is also the coordinator of the Wind Empowerment association, a global network for the promotion of locally manufactured small wind turbines.