Abstract: This paper takes Friedrich Engels 200th birthday on 28 November 2020 as occasion to ask: How relevant are Friedrich Engels’s works in the age of digital capitalism? It shows that Engels class-struggle oriented theory can and should inform 21st century social science and digital social research. Based on a reading of Engels’s works, the article discusses how to think of scientific socialism as critical social science today, presents a critique of computational social science as digital positivism, engages with foundations of digital labour analysis, the analysis of the international division of digital labour, updates Engels’s Condition of the Working Class in England in the age of digital capitalism, analyses the role of trade unions and digital class struggles in digital age, analyses the social murder of workers in the COVID-19 crisis, engages with platform co-operatives, digital commons projects and public service Internet platforms are concrete digital utopias that point beyond digital capital(ism). Engels’s analysis is updated for critically analysing the digital conditions of the working class today, including the digital labour of hardware assemblers at Foxconn and Pegatron, the digital labour aristocracy of software engineers at Google, online freelance workers, platform workers at capitalist platform corporations such as Uber, Deliveroo, Fiverr, Upwork, or Freelancer, and the digital labour of Facebook users. Engels’s 200th birthday reminds us of the class character of digital capitalism and that we need critical digital social science as a new form of scientific socialism.

Keywords: Friedrich Engels, 200th birthday, anniversary, digital capitalism, digital capital, digital labour, digital commons, The Condition of the Working Class in England, critical digital research, critical digital social science, scientific socialism, international division of digital labour, digital commodity, computational social science, digital positivism, social murder, COVID-19 crisis, coronavirus, pandemic, Foxconn, Pegatron, Google, software engineering, digital labour aristocracy, online freelancers, Uber, Deliveroo, Fiverr, Upwork, Freelancer, Facebook, class struggles, working class, public service Internet platforms, platform co-operatives, Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy; The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State; Anti-Dühring, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, Dialectics of Nature, Karl Marx

1.

Introduction

28 November 2020: Friedrich Engels was born 200 years ago on 28 November 1820. Together with Karl Marx, Engels was the founder of the critique of the political economy. He was a theorist, historian, journalist, philosopher, politician and entrepreneur who used the money capital he accumulated for support Marx and the international socialist movement. In 2020, capitalism has changed, but is still around. Engels’s 200th anniversary is a good occasion in order to ask: How relevant are Friedrich Engels’s works in the age of digital capitalism? This essay deals with this question.

Engels together with Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party, The German Ideology, and The Holy Family. Engels also helped out Marx with writing newspaper articles that appeared under Marx’s name. And he made a genuine contribution to critical theory with works such as Anti-Schelling (Schelling and Revelation), Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy, The Condition of the Working Class in England, The Housing Question, Anti-Dühring, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Dialectics of Nature; The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State; Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy. This article discusses the relevance of a variety of Engels’s works for the critical analysis of digital capitalism with a special focus on The Condition of the Working Class in England because we are interested in the condition of the working class in digital capitalism today.

Section 2

discusses the

role of history and class struggles in Engels’s works. It deals with the

question whether or not Engels was a vulgariser of Marx’s theory, who

advanced

a deterministic concept of history. Section 3 outlines a critique of

computational social science based on Engels’s understanding of

scientific

socialism. Section 4 analyses the digital condition of the working class

today.

It uses Engels’s works, especially his book The

Condition

of the Working Class in England, for analysing the digital labour

of hardware assemblers, Google software engineers, platform workers, and

Facebook users. The section also analyses the role of productivity gains

achieved by digital automation and robotisation and labour inequalities

in the

COVID-19 crisis. Section 6 discusses working class struggles in digital

capitalism. Section 6 draws conclusions.

2.

Engels,

History,

Class Struggles

Positions on the intellectual relationship of Marx and

Engels are split. There are on the one hand those who argue that

Engels

misunderstood, manipulated and vulgarised Marx’s theory and thereby

not just

turned Marx into Marxism but also laid the grounds for Stalinism (see

e.g. Carver 1981; 1983;

1990; Levine 1975;

2006; Schmidt 1971).

And

there are those who say that Engels made his own contributions to

socialist

theory, but that there is no major theoretical difference between Marx

and

Engels (see e.g. Blackledge 2019, Fülberth

2018; Kopf 2017; Krätke

2020; Mayer 1935). The representatives

of this position hold that Engels was a not just Marx’s best friend,

but also

his closest intellectual companion so that there would be not Marx

without

Engels.

Terrell Carver and Norman Levine are two of the theorists who hold the first position Carver (1981, 93) writes that Marx and Engels had “different approaches to social science and perhaps politics itself”. “Engels’s influence has chiefly been on the theoretical side of Marxism, and his ‘dialectics’ and ‘materialism’ are notably memorialized in official Soviet philosophy” (Carver 1990, 257). Levine (2018, 195-196) argues that Engels neglected: “Engelsian Leninism was founded upon the belief that the meteoric advancement of science made socialism attainable and therefore led to the prioritization of the forces of production. […] Engelsian Leninism rested upon de-politicization” (Levine 2018, 195-196). Levine’s arguments imply that there is a lack of focus on class struggle in Engels’s works.

Stalinism eulogised elements from some of Engels’s works. In his essay

“Dialectical and Historical Materialism”

published

in the History of the Communist

Party of

the Soviet Union Bolsheviks: Short Course – the ideological

bible of

Stalinism –, Stalin (1945) references and

quotes from

Engels’s Anti-Dühring, Dialectics of Nature, and Feuerbach and the End of

Classical German

Philosophy.

Stalin (1945) directly applies some aspects of

the dialectics of nature to society and claims that this means that

revolutions

and the transition to socialism are inevitable:

If the connection between the phenomena of nature and their interdependence are laws of the development of nature, it follows, too, that the connection and interdependence of the phenomena of social life are laws of the development of society, and not something accidental. Hence, social life, the history of society, ceases to be an agglomeration of ‘accidents’, for the history of society becomes a development of society according to regular laws, and the study of the history of society becomes a science (114).

Further, if the passing of slow quantitative changes into rapid and abrupt qualitative changes is a law of development, then it is clear that revolutions made by oppressed classes are a quite natural and inevitable phenomenon (111).

For Stalin, socialism as science

does not

mean a science of society that is different from the natural sciences,

but

deterministic and mechanical social laws of nature operating in

society. The

implication is for Stalin that history develops in a linear manner, it

is for

him a “process of

development from the lower to the higher” (Stalin

1939,

109). Stalin argues that the Soviet Union followed capitalism

and therefore

was a socialist system: “[T]he

U.S.S.R.

has already done away with capitalism and has set up a Socialist

system” (Stalin 1945, 119). His implication

was that

anyone critical of him was bourgeois and anti-socialist. The

mechanical

interpretation of the dialectic legitimated Stalin’s terror against

his

opponents.

The concepts of Aufhebung

(sublation) and the negation of the negation are missing in Stalinist

dialectics. They are however key features of Engels’s dialectics.

Stalin

referred to Engels, but Engels’s interpretation of dialectics was

other than

Stalin’s not based on mechanical and deterministic concepts. Engels is

not be

blamed for Stalinism.

In Engels’s canonical works, there are some problematic formulations.

For example, he writes that “the

capitalist

mode of production has likewise itself created the material

conditions from which it must perish” (Engels

1878, 122)

or that there is the “inevitable downfall” of the

capitalistic mode of

production (Engels 1880, 305). Such

formulations

create the impression that society is governed by mechanistic and

deterministic

laws.

But Engels (1878)

stresses in the same works where the mentioned problematic

formulations can be found

that there is a difference between the negation of the negation in

nature and

in society. The dialectic has in each realm of the world “specific

peculiarities” (Engels 1878, 131). The

“history of the

development of society turns out to be essentially different from that

of

nature” because humans “are all endowed with consciousness, are men

acting with

deliberation or passion, working towards definite goals” (Engels

1888,

387). Humans would act with intentions towards specific goals,

but

the outcomes would often be quite different from the intentions, which

is an

element of chance in society that is, however, “governed by inner,

hidden laws”

(Engels 1888, 387). He describes the

proletarian

revolution as the solution of capitalism’s contradictions (Engels

1880, 325).

“To accomplish this act of universal emancipation is the historical

mission of

the modern proletariat”. A mission does not necessarily succeed. In

these

passages, Engels stresses that society operates on dialectical laws

that are

different from the laws of nature. The question is, however, what a

law is in

society. The more problematic formulations that can be found in these

works can

imply that capitalism automatically breaks down. But more frequently

Engels

stresses in the same works that history is the history of class

struggles, for

example: “In modern history at least it

is,

therefore, proved that all political struggles are class struggles,

and all

class struggles for emancipation, despite their necessarily

political form –

for every class struggle is a political struggle – turn ultimately

on the

question of economic emancipation“ (Engels

1888,

387-388, 391). It is one of the laws of society that change

happens

through human practices and that in class society, class struggle is

the

decisive practice of transformation.

This assumption is also in line with Marx’s and Engels’s view of history

in their early works. In The

Holy Family,

the first work that Marx and Engels co-authored, Engels writes: “History

does

nothing, it ‘possesses no immense wealth’, it ‘wages

no battles’.

It is man, real, living man who does all that, who possesses

and fights;

‘history’ is not, as it were, a person apart, using man as a means to

achieve its

own aims; history is nothing but the activity of man

pursuing his

aims” (Marx and Engels 1845, 93). In The Manifesto of the Communist

Party,

Marx and Engels (1848b, 482) say: “The

history

of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”.

Marx added

to the law of class struggle the law of the dialectic of structures

and agency,

of societal conditions and practices. Humans “make their own history,

but they

do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under

circumstances

chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered,

given and

transmitted from the past” (Marx 1852, 103).

Society’s

transformation is based on dialectics of chance/necessity,

freedom/determination, discontinuity/continuity, practices/structural

conditions. In capitalism, the class contradiction and the

contradiction

between productive forces and relations of production with necessity

call forth

crises. The outcome of such crises is not determined and depends on

the results

of class struggles. Society’s dialectic is a dialectic of objective

contradictions and the human subjects’ practices.

If Marx and Engels had assumed that capitalism would automatically break

down and socialism would emerge inevitably, why would they have

engaged in

practical revolutionary activity? Engels participated, for example,

active in

the 1849 revolutionary uprising for democracy in Elberfeld and Baden.

Marx and

Engels were leaders of the League of the Just, the Communist League,

and the

First International. Engels’s single deterministic historical

formulations seem

to have served the rhetorical-political purpose of motivating

revolutionary

optimism among activists.

In a letter to Borgius, Engels (1894) stresses

that humans “make their history themselves, only in given

surroundings

which condition it and on the basis of actual relations already

existing, among

which the economic relations” form “the red thread which runs through

them”.

The notion of the economic as read thread allows us to see the economic,

i.e.

social production, as the universal and common element of all social

realms.

Social production takes on different forms with emergent meanings but

also is

the red thread of society and its various spheres (see Fuchs

2020a).

Blackledge (2019, 240) stresses that by

scientific socialism Engels did not understand “empiricism or

positivism” and

“a mechanical and fatalistic model of agency. “Engels was neither an

empiricist

nor a positivist. And as regards the charge of reductionism, he held

to a

stratified view of natural and social reality according to which

emergent

properties at each level could neither be reduced to laws governing

the levels

below them, nor could the laws through which they operated be

understood in an

empiricist or positivist fashion”.

Engels stresses in Socialism:

Utopian and Scientific in line with Marx’s Grundrisse and Capital that

science

and technology are on the one hand “the most powerful weapon in the

war

of capital against the working-class” (Engels

1880, 314)

and on the other hand important means of emancipation from capitalism

and class

society that support the establishment and reproduction of “the

kingdom of

freedom” beyond necessity (Engels 1880, 324).

Taken together, there is no doubt that there are some problematic

formulations in Engels’s canonical works. But a more pertinent reading

is that

he and Marx interpreted history as a dialectic of class struggles and

structural conditions, which implies that there is no automatic

breakdown of

capitalism. The implication is also, as Tristam Hunt (2009,

361) stresses in his Engels-biography that Engels and Marx are

not to blame

for Stalin’s terror:

In no intelligible sense can Engels or Marx bear culpability for the crimes of historical actors carried out generations later, even if the policies were offered up in their honor. Just as Adam Smith is not to blame for the inequalities of the free market West, nor Martin Luther for the nature of modern Protestant evangelicalism, nor the Prophet Muhammad for the atrocities of Osama bin Laden, so the millions of souls dispatched by Stalinism (or by Mao’s China, Pol Pot’s Cambodia, and Mengistu’s Ethiopia) did not go to their graves on account of two nineteenth-century London philosophers.

Although there are single

problematic passages in Engels’s works that imply that capitalism must

automatically collapse, there are other passages that stress the

difference of

dialectical laws in nature and society and that a key social law found

in class

societies is that humans make their own history under given conditions

and in

class societies do so in the form of class and social struggles.

Scientific socialism

doesn’t mean that society is governed by mechanical laws, but that

socialist

research studies society based on the combination of critical social

theory and

critical empirical social research.

3.

Computational

Social

Science and Scientific Socialism

To

speak

of “scientific socialism” doesn’t automatically and not necessarily

apply

a mechanistic and deterministic theory of society that assumes that

capitalism

automatically breaks down and society is determined by natural

economic laws.

The scientific understanding of socialism is not a natural science

applied

society but rather a social science of society (Gesellschaftswissenschaft) that stresses the key role of the

conscious human being, social practices, social production, and social

relations in society. Natural science theories are not necessarily

deterministic and mechanistic. The point is that in the social

sciences, the

positivist tradition treated society based on natural science methods

and

mathematics, which focuses on pure quantification and assumes that

everything

can be calculated. The logic of positivism neglects society’s

qualities and the

fact that not everything social and societal is calculable. We cannot

properly

calculate love, morals, sadness, happiness, (dis)respect, (in)justice,

solidarity,

etc. Society’s social qualities can only be properly analysed by

qualitative

social research methods. Marx and Engels are not as such opposed to

calculation

and quantification, but they are critical of computing as means of

domination

and exploitation that drives capital accumulation and makes the

qualities of

society disappear behind things and numbers. This critique of

quantification as

aspect of capitalist accumulation has been reflected in Georg Lukács’

(1971) notion of reification and Max

Horkheimer’s (1947) notion of

instrumental reason.

In

the contemporary social sciences,

computational social sciences have emerged as a dominant paradigm that

attracts

lots of attention, support, funding and has increasingly been

institutionalised.

David Lazer et al. (2009, 722) define

computational social science as social science that “leverages the

capacity to collect

and analyze data with an unprecedented breadth and depth and scale”

and

operates with “terabytes of data”. In the textbook Introduction to Computational Social Science, Cioffi-Revilla (2014,

2) defines computational social science:

“The new field of Computational Social Science can be defined as the

interdisciplinary investigation of the social universe on many scales,

ranging

from individual actors to the largest groupings, through the medium of

computation. […] Computational social science is based on an information-processing

paradigm of

society” (Cioffi-Revilla 2014, 2).

The Manifesto of Computational

Social Science (Conte et al. 2012)

argues that

computational social science operates with “massive ICT data” (327),

conducts “massive data analysis” (330)

that operates “up to the whole world population”

(331). It is “a

new

field of science in which new type of data, largely made available

by new ICT

applications, can be used to produce large-scale computational

models of social

phenomena” (333). The Manifesto claims that computational social science constitutes

“a

new era” (327).

Computational social scientists set out to radically transform the

social sciences. Computational social science is a new positivism. Its

methods

cannot understand the qualitative features of society such as

motivations,

norms, moral values, feelings, ideologies, experiences.

Cioffi-Revilla (2014, 1) explicitly

situations computational social science in the context of Auguste

Comte’s

“natural science of social systems, complete with statistical and

mathematical

foundations”. Comte was the founder of positivism. Computational

social science

explicitly stands in the context of positivism. The Manifesto of Computational Social Science argues for turning

sociology and the social sciences into a natural science: “sociology

in particular and the social sciences in

general would undergo a dramatic paradigm shift, arising from the

incorporation

of the scientific method of physical sciences” (Conte

et

al. 2012, 341).

The danger is that computer science colonises the social sciences and

leaves no space and time for critical theory, social theory,

philosophy. The

main danger of the computational social sciences is that it makes the

social

sciences uncritical and turns them into administrative sciences (see Fuchs 2017a). Engels warned in a different

context of

the dangers of positivism. He argues against a mathematical method

that is

“reducing qualitative differences to merely quantitative differences

[…] As

Hegel has already shown (Encyclopädie, I, S. 199), this

view, this

‘one-sided mathematical view’, according to which matter must be

looked upon as

having only quantitative determination, but, qualitatively, as

identical

originally, is ‘no other standpoint than that’ of the French

materialism of the

eighteenth century. It is even a retreat to Pythagoras who regarded

quantitative determination as the essence of things” (Engels

1925,

534). For Engels (1925, 469), such

reductive approaches are a form of “naïve materialism”.

Engels criticises mechanical materialism that does not see and analyse

the qualitative and dialectical aspects of the world. Engels in this

passage

refers to the first part of Hegel’s Encyclopaedia,

where Hegel discusses the dialectical logic. The reference is to the

discussion

of pure quantity as aspect of quantity. Hegel writes in this passage

that “when

we look closely at the exclusively mathematical standpoint that is

here

referred to (according to which quantity, which is a definite stage of

the

logical Idea, is identified with the Idea itself) we see that it is

none other

than the standpoint of Materialism”

(Hegel 1830/1991, 159, addition to §99). He

stresses that

“freedom, law, ethical life […] cannot be measured and computed or

expressed in

a mathematical formula” (Hegel 1830/1991, 159,

addition to §99) and that “we know very little about these things and

the

distinction between them, if we simply stick to a ‘more or less’ of

this kind,

and do not advance to some grasp of specific determinacy, which is

here in the

first place qualitative” (Hegel 1830/1991, 160,

addition to §99).

Hegel and Engels remind us that computational social science cannot

grasp society’s dialectical relations that are not easily

quantifiable. It

cannot understand, model, calculate freedom, law, moral judgement,

love, etc.

Its analyses are one-dimensional. Critical social science should

certainly

adopt and experiment with data-driven methods, but not at the expense

of the

engagement with and application of critical theory (Fuchs

2017a). Digital data gathered on social media and other

data-intensive

environments can reveal important aspects of life in contemporary

societies.

What is needed are not simply new forms of prediction and

quantification, but

critical, creative and experimental methods that combine aspects of

quantitative data with a qualitative understanding of humans’

motivations, experiences,

interpretations, norms and values (Fuchs 2017a).

Whereas

Marx and Engels were social scientists who wrote the Communist

Manifesto, some contemporary

social scientists write manifestos for a new positivism and many more

believe

in what such manifestos postulate, which results in the

institutionalisation of

computational social science and big funding for big data-based

methods and

project. Big data analytics and computational social science miss the

difference between society and nature that Engels points out. The

danger is

that they reduce society to quantitative data and neglect its

indeterminate,

open, dialectical qualities.

To speak of “scientific socialism” doesn’t automatically and not

necessarily apply a mechanistic and deterministic theory of society

that

assumes that capitalism automatically breaks down and society is

determined by

natural economic laws. The scientific understanding of socialism is

not a

natural science applied society but rather a social science of society

(Gesellschaftswissenschaft)

that stresses

the key role of the conscious human being, social practices, social

production,

and social relations in society. Natural science theories are not

necessarily

deterministic and mechanistic. The point is that in the social

sciences, the

positivist tradition treated society based on natural science methods

and

mathematics, which focuses on pure quantification and assumes that

everything

can be calculated.

The logic of positivism neglects society’s qualities and the fact that

not everything social and societal is calculable. We cannot properly

calculate

love, morals, sadness, happiness, (dis)respect, (in)justice,

solidarity, etc.

Society’s social qualities can only be properly analysed by

qualitative social

research methods. Marx and Engels are not as such opposed to

calculation and

quantification, but they are critical of computing as means of

domination and

exploitation that drives capital accumulation and makes the qualities

of

society disappear behind things and numbers. This critique of

quantification as

aspect of capitalist accumulation has been reflected in Georg Lukács’

(1971) notion of reification and Max

Horkheimer’s (1947) notion of

instrumental reason.

Computational

social

science is a paradigm in the social sciences that propagates

mathematical

models of society that use big data and predictive algorithms. Engels’s

scientific socialism is critical of positivism. Computational social

science is

a neo-positivism that neglects that qualitative features of society such

as

motivations, norms, moral values, feelings, ideologies, experiences,

love,

death, freedom, or (in)justice that cannot be reduced to mere

quantities.

Computational social science poses the danger of turning the social

sciences

into administrative, instrumental, positivist research that supports

domination

and exploitation and is a branch of computer science that has colonised

the

social sciences.

4.

The

Digital

Condition of the Working Class Today

In this section, we will discuss the situation of the working class in digital capitalism. Engels’s book The Condition of the Working Class in England plays an important role as starting point for such an analysis. The section introduces Engels’s book (subsection 4.1), the relationship of technology and society (subsection 4.2), digital technology and relative surplus-value production (subsection 4.3), absolute surplus-value production at Foxconn (subsection 4.4), play labour at Google (subsection 4.5), precarious platform workers (subsection 4.6), labour in the COVID-19 crisis (subsection 4.7), and Facebook labour (subsection 4.8).

4.1.

The

Condition

of the Working Class in England

The Condition of

the Working Class in

England

(CWCE) is for many Engels’

most

influential book. Eric J. Hobsbawm writes that “the Condition is

probably

the earliest large work whose analysis is systematically based on the

concept of the Industrial Revolution” (Hobsbawm

1969,

17). It “remains an indispensable work and a landmark in the

fight for the

emancipation of humanity” (Hobsbawm 1969, 17).

David

McLellan (1993, xix) writes that the Condition

is “the first book to have

dealt comprehensively with the industrial working class as a whole

rather than

just with particular groups or industries”. Engels’s method was a

“[r]ich and

complex” form of interdisciplinarity that combined “economics,

philosophy, and

labour history” (McLellan 1993, xix).

Engels

integrated a “rich mass of material” into “an extraordinary unity […]

articulated […] under […] general principles” (Mayer

1935,

62)

Engels

came from a bourgeois family. His

father Friedrich Engels senior (1796-1860) owned the cotton factory

Ermen &

Engels that operated two cotton mills, one in Engelskirchen

(Rhineland) and one

in Manchester (United Kingdom).

Engels

junior conducted the research for

his book The Condition of the

Working

Class in England (CWCE =

Engels 1845) during his stay in

Manchester from 1842

until 1844, where he was supposed to learn his father’s trade. Engels

directly

experienced the working class’ conditions in England and got in touch

with

workers, from whom he learned about their everyday life and the

problems they

faced. Family status does not determine one’s political worldview.

Born into a

capitalist family, Engels became one of the international leaders of

the

communist movement. There is no 1:1 relationship and no mechanic

determination

of culture by the economy. Engels junior became his father’s

representative in

the Manchester business. After the death of his father in 1860, Engels

became

the co-owner of the Manchester establishment. He managed the company,

funded

Marx’s life in London, financially and intellectually supported the

socialist

movement, and was active as a writer. In 1869, Engels had accumulated

enough

wealth in order to be able to sustain himself and Marx and family, and

support

the socialist movement. He sold his share in Ermen & Engels,

retired from

the company, and entirely devoted himself to the socialist movement

and theory.

In

CWCE, Engels analyses the

rise, early

development and consequences of capitalism in England. The decisive

features he

mentions are a) the working class, b) industrial technologies such as

the

steam-engine as moving technology and manufacturing machinery as

working

technology that replaced handicraft, c) the capitalist class, and d)

the

division of labour.

In

CWCE,

Engels analyses the terrible conditions that the working class had

to

endure in industrial England, including long working hours, low wages,

poverty,

overcrowded and dirty slums and dwellings, poisonous and uneatable

food,

overwork, starvation, death by hunger, lack of sleep, air pollution,

untreated

illnesses, egotism and moral indifference, crime, alcoholism, bad

clothes,

unemployment, rape, homelessness, lack of clean water, drainage and

sanitation,

illiteracy, child labour, military drill in factories, overseers’

flogging and

maltreatment of workers, deadly work accidents, fines, etc.

Engels

characterises the misery the

working class faces as “a condition unworthy of human beings” (CWCE, 43),

conditions where humans cannot

“think, feel, and live as human beings” (CWCE, 220),

degradation

to “the lowest stage of humanity” (CWCE, 73),

treatment

of workers “as mere material, a mere chattel” (CWCE, 66).

Engels

characterisation of capitalism as dehumanising resembles Marx’s

introduction of the notion of alienation in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, where Marx (1844,

517) speaks of one aspect of alienation as “alienation

of the human being from being

human”[1].

Out of such words speaks the deep humanism of Engels and Marx. They

both

understand socialism is a humanist society that enables a good life

for all

humans.

Using

factory inspectors’ reports,

parliamentary reports, observation, and the analysis of news reports,

The Condition of the Working

Class in

England shows that Engels already in the 1840s practiced and

pioneered

empirical social research (Kurz 2020, 67; Krätke 2020, 29-34; Zimmermann

2020). In Capital Volume

1, Marx

(1867) uses the same empirical method as

Engels in

CWCE, which shows that Engels’s work had large influence on Marx. Marx

(1867, 349 (footnote 15), 573, 755),

explicitly refers

positively to Engels’s book several times. For example, Marx (1867,

349 [footnote 15]) writes:

How well Engels understood the spirit of the capitalist mode of production is shown by the Factory Reports, Reports on Mines, etc. which have appeared since 1845, and how wonderfully he painted the circumstances in detail is seen on the most superficial comparison of his work with the official reports of the Children's Employment Commission, published eighteen to twenty years later (1863-7).

Working on Capital, Marx re-read Engels’s Condition and wrote to him about the book: “With what zest and passion, what boldness of vision and absence of all learned or scientific reservations, the subject is still attacked in these pages!” (Marx 1863, 469).

4.2.

Technology

and

Society

Some observers, such as McLellan (1993, xviii) argue that underlying Engels approach in CWCE is “a technological determinism that was to remain with Engels all his life”. There are indeed some formulations in CWCE that can create such an impression: The “industrial revolution […] altered the whole civil society” (CWCE, 15); the “proletariat was called into existence by the introduction of machinery” (CWCE, 29)

But Engels leaves no doubt that capitalist relations of production, i.e.

private property relations, the class relation between capital and

labour and

the profit imperative, shape the development and application of

machinery. He

says that capitalism is the cause of misery: The “great central fact”

is “that

the cause of the miserable condition of the working class is to be

sought […]

in the capitalistic system

itself” (CWCE, 314). When discussing

machinery,

Engels points out that the social conditions under which technology

exist are

the factors that have decisive influence on technology’s impacts on

society:

“The consequences of improvement in machinery under our present social

conditions are, for the working man, solely injurious, and often in

the highest

degree oppressive” (CWCE, 149).

In CWCE, Engels often describes class relations as competition and makes

clear that not machines, but transformation of class relations created

the

proletariat. Competition – “the battle of all against all” – “created

and

extended the proletariat” (CWCE, 87).

Capitalist competition means a class conflict between capital and

labour but

also competition between capitalists that results in the

centralisation of

capital and competition between workers, such as between the

“power-loom

weaver” and “the hand-loom weaver” (CWCE, 87).

Engels (Marx and Engels 1848b, 482)

inserted a note to the 1888 edition of the Manifesto,

saying that by “bourgeoisie is meant the class of modern Capitalists,

owners of

the means of social production and employers of wage-labour. By

proletariat,

the class of modern wage-labourers who, having no means of production

of their

own, are reduced to selling their labour-power in order to live”.

Capital means

“the direct or indirect control of the means of subsistence and

production” as

“the weapon with which this social warfare is carried on” (CWCE, 37-38).

The

bourgeoisie is the class of property-holders (CWCE, 281).

The

bourgeoise measures “[a]ll the conditions of life […] by money” (CWCE, 282).

The decisive aspect of

technology in capitalism is that capitalists own technologies as

private

property that is a means of production used for accumulating capital

and the

production of surplus-value and commodities.

Also in Outlines of a Critique of

Political Economy, a foundational text of Marx’s and Engels’s

approach,

young Engels (1843, 442-443)

stresses that science and technology are instruments in the hands of

the

bourgeoisie:

In

the struggle of capital and land against labour,

the first two elements enjoy yet another special advantage over labour

– the assistance

of science; for in present conditions science, too, is directed

against labour.

Almost all mechanical inventions, for instance, have been occasioned

by the

lack of labour-power; in particular Hargreaves’, Crompton’s and

Arkwright’s

cotton-spinning machines. There has never been an intense demand for

labour

which did not result in an invention that increased labour

productivity

considerably, thus diverting demand away from human labour. The

history of

England from 1770 until now is a continuous demonstration of this. The

last

great invention in cotton-spinning, the self-acting mule, was

occasioned solely

by the demand for labour, and rising wages. It doubled machine-labour,

and

thereby cut down hand-labour by half; it threw half the workers out of

employment,

and thereby reduced the wages of the others by half; it crushed a plot

of the

workers against the factory owners, and destroyed the last vestige of

strength

with which labour had still held out in the unequal struggle against

capital.

Marx

(1859, 264) characterised the Outlines as “brilliant essay on the critique of economic

categories” and directly referred to it several times in Capital

Volume I (Marx 1867, 168 [footnote 30], 253

[footnote

5], 266-267 [footnote 20], 788

[footnote 15]). In the Outlines, Engels points out

that “the mental element of invention, of thought” (Engels

1843,

427), as in the form of science, is part of human labour and the

“human, subjective side, labour” (427) of

production.

In work, the human being is “active physically and mentally” (428).

Engels here on the one hand points out the

dialectic of mental and physical activity in work and on the other

hand

identified mental work, or what today is often called knowledge or

information

work, as important aspect of production.

The assumption that Engels was a

technological determinist cannot be sustained. He analysed technology

in

capitalism as embedded into class relations so that there is

capitalist

ownership of technology as private-property that is utilised as means

for the

production of surplus-value, commodities, and profit.

4.3.

Digital Technology and Relative Surplus-Value Production

In the Grundrisse, Marx (1857/58) introduced the notion of surplus-value, by which he means that workers produce unpaid labour during a portion of the working by that capitalists appropriate and turn into monetary profit. Marx (1867, 645) distinguishes two methods of surplus-value production: “The production of absolute surplus-value turns exclusively on the length of the working day, whereas the production of relative surplus-value completely revolutionizes the technical processes of labour and the groupings into which society is divided”. Absolute surplus-value production means the lengthening of the unpaid part of the working day. Relative surplus-value production is the increase of productivity so that more value is produced during a certain time period than before. Engels anticipated both concepts in CWCE.

Engels gives many concrete examples of the increase of productivity through the introduction of new technologies. In the cotton industry, the invention of the jenny “made it possible to deliver more yarn than heretofore” (CWCE, 18). The introduction of the power-loom further increased the productivity of the English cotton industry: “In the years 1771-1775, there were annually imported into England rather less than 5,000,000 pounds of raw cotton; in the year 1841 there were imported 528,000,000 pounds, and the import for 1844 will reach at least 600,000,000 pounds” (CWCE, 21). Similar productivity increases could be observed in other industries, for example the manufacturing of wool: “In 1738 there were 75,000 pieces of woollen cloth produced in the West Riding of Yorkshire; in 1817 there were 490,000 pieces, and so rapid was the extension of the industry that in 1854, 450,000 more pieces were produced than in 1825. In 1801, 101,000,000 pounds of wool (7,000,000 pounds of it imported) were worked up; in 1855, 180,000,000 pounds were worked up, of which 42,000,000 pounds were imported” (CWCE, 22-23).

Engels describes the phenomenon of relative surplus-value production, but did not have a theoretical concept naming this process. Marx later introduced based on Engels the concepts of surplus-value and the methods of surplus-value production.

Since the middle of the 20th century, The capitalist invention and the capitalist application of digital production technologies has led to significant increases of productivity. Just like Engels observed the impacts of technologies such as the steam-engine and the power-loom, we today can observe the effects of the digitalisation of production that has increased productivity.

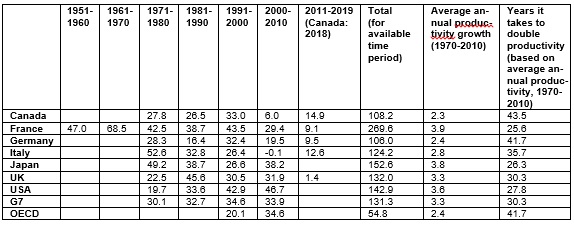

Table 1: Total annual labour productivity growth in manufacturing in percentage, productivity is measured as labour productivity per unit labour input (in most cases gross value added in constant prices per hour worked), data source: OECD STAN

Table 1 shows productivity growth

data for

the G7-economies. It uses labour productivity growth as a measure of

productivity. Labour productivity is a statistical measure of the

gross value

added (measured in constant US$) produced per hour worked in a

particular

industry. It calculates labour productivity by diving the total value

added in

an industry during one year by the total amount of working hours in

that

industry. The data in table 1 shows the ten-year growth rate of labour

productivity. Not all data was available, so some fields have been

left

undefined. In advanced capitalist countries, labour productivity has

more than

doubled over a time period of forty years (1970-2010). In the analysed

national

economies, it takes on average between 26 and 44 years to double the

productivity of manufacturing. This was also the time when computing

was

introduced in manufacturing as a production technology. Capitalist

digitalisation has resulted in large productivity growth in

manufacturing and

other industries.

Industry 4.0 is about technologies that combine the Internet of Things,

Big Data, social media, cloud computing, sensors, artificial

intelligence and

robotics in the production, distribution and use of physical goods.

The

bourgeoisie has declared the fourth industrial revolution to try to

automate

the production, distribution, handling, repair and disposal of

industrial goods

such as cars (Fuchs 2018c). It hopes to

increase the

profit rate of the manufacturing industry.

Engels pointed out that the capitalist shaping and use of industrial

technologies turned workers into “machines pure and simple” (CWCE, 17).

The capitalist shaping,

development, design and use of digital technologies has contributed to

forms of

alienation such as the enslavement of mine workers who extract the

physical

resources out of which digital hardware is manufactured, long working

hours in

the assemblage of hardware and in the

software and creative industry, an always-on-work-culture

mediated by

laptops, phones and tablets as means of production, precarious

freelancing in

the digital industries, etc.

4.4.

Absolute

Surplus-Value

Production at Foxconn

Engels gives a picture of the

terrible

conditions that members of the working

faced

in England in the 1840s. One of his examples are the dress-makers in

London:

They employ a mass of young girls – there are said to be 15,000 of them in all – who sleep and eat on the premises, come usually from the country, and are therefore absolutely the slaves of their employers. During the fashionable season, which lasts some four months, working-hours, even in the best establishments, are fifteen, and, in very pressing cases, eighteen a day; but in most shops work goes on at these times without any set regulation, so that the girls never have more than six, often not more than three or four, sometimes, indeed, not more than two hours in the twenty-four, for rest and sleep, working nineteen to twenty-two hours, if not the whole night through, as frequently happens! The only limit set to their work is the absolute physical inability to hold the needle another minute (CWCE, 217).

Here's another example of long

working hours

that Engels describes:

Other manufacturers were yet more barbarous, requiring many heads to work thirty to forty hours at a stretch, several times a week, letting them get a couple of hours of sleep only, because the night-shift was not complete, but calculated to replace a part of the operatives only. […] The consequences of these cruelties became evident quickly enough. The Commissioners mention a crowd of cripples who appeared before them, who clearly owed their distortion to the long working hours. This distortion usually consists of a curving of the spinal column and legs (CWCE, 161-162).

What Engels analyses here is the

method of

absolute surplus-value production. Capitalist have the interest to

make workers

produce commodities for as many hours per day and per week as possible

for as

little wage as possible. Long hours and small wages promise high

profits.

Absolute surplus-value production is also an important method of

surplus-value production in 21st-century digital capitalism. In the

period from

1992 until 2019, the number of agricultural workers in China decreased

from 350

million to 120 million, the number of manufacturing workers increased

from 180

million to 200 million, and the number of service workers went from

120 million

to 440 million[2].

Unlike economic development in Western capitalism, where the rise of

the

service and information industries was accompanied by the shrinking of

agriculture and manufacturing, China’s capitalism with Chinese

characteristics

(Harvey 2005, chapter 5) combines

industrialisation

and informatisation as simultaneous processes.

Western transnational digital corporations such as Apple, Dell, HP, and

AsusTek make use of Chinese large and comparatively cheap labour force

in order

to export capital so that digital hardware is assembled in China by

workers

contracted by suppliers such as Foxconn, Pegatron, Compal Electronics,

or

Wistron. The goal is to increase profits by minimising labour costs.

Students & Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM) (2011) reported that workers at the Chinese factories at Foxconn, where iPhones and other hardware is assembled, faced conditions such as military drill, forced and unpaid overtime, fines such as the non-payment of wages, crowded accommodations, low wages, compulsory internships, toxic workplaces, etc. In 2010/2011, nineteen young Foxconn workers aged between 17 and 28 attempted to commit suicide by jumping from Foxconn buildings. Most of them died. They could no longer stand the terrible working conditions.

China Labor Watch (2017,

1, 3) conducted research in order to find

out how the working conditions look like in the factories of the Apple

suppliers Compal, Foxconn, Green Point, and Pegatron:

In all of the four factories, weekly working hours surpassed 60 hours and monthly overtime hours surpassed 90 hours, with most overtime amounting to of 136 hours over a month. […] Workers were required to sign an agreement to voluntarily do overtime, opt out of paying for social insurance and opt out of housing funds. These acts are blatant attempts to evade responsibilities and are clear violations against China’s Labor Law. […] Workers at Pegatron and Green Point were continuously working overtime without compensation. […] Both excessive working hours and tremendous pressure are severe problems at Foxconn. Since 2010, there have been more than 10 suicides, indicative of the terrible working conditions and rigid management. In September 2016, [a] CLW [China Labour Watch] investigator launched another undercover investigation at Foxconn. […] Most workers there had accumulated 122 hours of overtime each month […], far exceeding the legal limit of 36 hours per month as per China’s labor laws.

Just like the dress-makers whose

labour

Engels analysed in the 1840s, 21st-century digital hardware assemblage

workers

at Foxconn, Pegatron and other suppliers are a largely young and

female

workforce that is highly exploited. Capitalist hardware corporations

try to

make workers conduct a high number of weekly working hours for low pay

and with

unpaid overtime in order to minimise production costs so that these

transnational corporations profits can be maximised. The Chinese

manufacturing

industry is part of a global capitalist system, in which transnational

corporations outsource labour to Asia in order to accumulate capital

by making

use of the method of absolute surplus-value production. China’s large

working

class, whose members often leave rural areas in order to find work in

urban manufacturing

centres, is transnational corporations’ source of cheap and highly

exploited

labour.

4.5.

Play

Labour

at Google

Engels describes a faction of the

working

class that was relatively privileged. These were workers whose “state

of misery

and insecurity in which they live now is as low as ever” (CWCE, 321).

He

terms these workers the labour aristocracy, “an aristocracy among the

working-class” (engineers, carpenters, joiners, bricklayers) that has

“succeeded in enforcing for themselves a relatively comfortable

position” (CWCE,

321). Lenin (1920,

194) uses the notion of the labour aristocracy for

“workers-turned-bourgeois”, “who are quite philistine in their mode of

life, in

the size of their earnings and in their entire outlook”. “They are the

real agents

of the bourgeoisie in the working-class movement, the labour

lieutenants of

the capitalist class”.

Software engineers are a digital labour aristocracy. They tend to earn

very high wages, which gives them a privileged position. The demand

for their

labour-power is very high. Although many software engineers are

relatively rich

money-wise, they are socially poor. They often lack social relations

friendships, outside of the office. They spend most of their time in

offices

such as the Googleplex, where they work long hours. Many software

companies

want to keep them in the office by providing facilities for sports,

entertainment, relaxation, etc. The Googleplex more looks like a

playground

than an office. In the life of software engineers, labour and play

converge.

Google workers are playworkers, workers for whom labour feels like

play.

Google workers in comparison to ICT manufacturers have much higher wages

and privileges, which also means that they are more unlikely to

resist, which

is, as Engels describes, typical for the labour aristocracy: “they are

very

nice people indeed nowadays to deal with, for any sensible capitalist

in

particular and for the whole capitalist class in general” (CWCE, 321).

This passage from Friedrich Engels’s book The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 describes

typical working conditions in the phase of the industrialization of

capitalism:

work in factories was mentally and physically highly exhausting, had

negative

health impacts, and was highly controlled by factory owners and

security

forces.

The manufacturing labour that Engels analysed in the 1840s was

physically highly exhausting. Programming does not require engineers

to burn

lots of energy. Whereas manufacturing labour feels like toil, Google

labour

tends to feel like play.

Like at the time of Engels engineers, carpenters, joiners, bricklayers,

in digital capitalism software engineers hold qualifications and

produce goods

that are in high demand and allow achieving relatively high wages and

income.

The poor workers who Engels portrays in CWCE

as toiling in industries such as cotton and wool manufacturing,

dress-making,

etc. were compelled to work long hours by poverty wages and the

“silent

compulsion of economic relations” (Marx 1867, 899)

of

the labour-market that makes them starve if they don’t sell their

labour-power.

Poverty-wages were used as a means of coercion, as a method of

absolute

surplus-value production. The contemporary digital labour aristocracy

also

faces the silent compulsion of having to sell their wages. But these

wages are

very high because they work in a highly productive industry that

produces a key

commodity – software – that plays an influential role in almost all

parts of

the 21st century society. Digitalisation transforms all

aspects of

society, which is why software is in high demand and allows achieving

high

profits and commodity prices. Those who possess the key skill of

knowing how to

code software can therefore in turn achieve high wages. Absolute

surplus-value

production takes on a new form in this industry: software engineers

often sign

all-inclusive contracts that fixes a certain wage-sum per month

without

extra-pay for overtime. In the USA, the Fair US Labor Standards Act

(Section 13

[a] 17) enables software corporations such as Google not to pay

overtime if

there is an hourly wage of at least US$ 27.63. This law legally enacts

absolute surplus-value

production in

the US software industry.

In addition, new management methods

that try to blur the distinction between labour-time/spare-time and

between

workspace/private spaces are often used in software corporations in

order to

keep the workers in the company for long hours, which makes them work

overtime

and to experience the long hours they spend in their employers’

premises not as

alienation, but as play and fun. The result is that they work longer

hours that

are unpaid. Absolute surplus-value production in key sectors of 21st

century digital capitalism such as the software industry takes on the

form of

play labour.

The first, second, and third edition of my book Social Media: A Critical Introduction contains a chapter about the

critique of the political economy of Google (Fuchs 2014, chapter 6; Fuchs

2017b,

chapter 6; Fuchs 2021, chapter 5).

For this

chapter, I analysed online forums, where Google workers report on

their working

conditions. I updated this analysis for each edition (2014,

2017, 2021). The

working

conditions at Google stayed constant during this time: Google

employees enjoy

the content of their job, the perks such as free food and working for

a

high-reputation brand, but complain about the lack of work-life

balance. When

asked about working conditions at Google, they typical Google

software-engineer

says that “work/life

balance is

nearly non-existent” and one must be prepared to “work all day and

night long”

(Fuchs 2021, chapter 5).

Google employees enjoy the idea of

working

in a high-reputation company, tend to find their work tasks

interesting, like

the perks such as free food, but tend to complain about the long

working hours,

a lot of overtime, and the lack of work‒life balance. Lack of

work-life

balance at companies such as Google mays a playful work environment

that turns

spare-time into unpaid labour-time.

Luc Boltanski

and Ève Chiapello (2005) speak

in this

context of the “new spirit of capitalism”. The new spirit of

capitalism is a

management method and management ideology. It promises labour that is

characterised by

autonomy, spontaneity, rhizomorphous capacity, multitasking (in contrast to the narrow specialization of the old division of labour), conviviality, openness to others and novelty, availability, creativity, visionary intuition, sensitivity to differences, listening to lived experience and receptiveness to a whole range of experiences, being attracted to informality and the search for interpersonal contacts (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005, 97).

Such

promises

“are taken directly from the repertoire of May 1968” (Boltanski

and Chiapello 2005, 97). The new

spirit of capitalism is a work culture of creativity, play, and fun

that

capital uses as new, sophisticated method of absolute surplus-value

production

that blurs establish distinctions and demarcations of space and time

in the

economy. Inspired by Boltanski and Chiapello, Eran Fisher summarises

these

changes in the following way:

It

is therefore best understood in

terms of the eradication of the distinctions between these components:

between companies

and the network, producers and consumers, producers and users, labor and

fun,

forces of production and the production process, and so forth. These

established industrial demarcations (and more specifically, part and

parcel of

the Fordist phase of capitalism) are now overturned with the emergence

of

network production (Fisher 2010, 140).

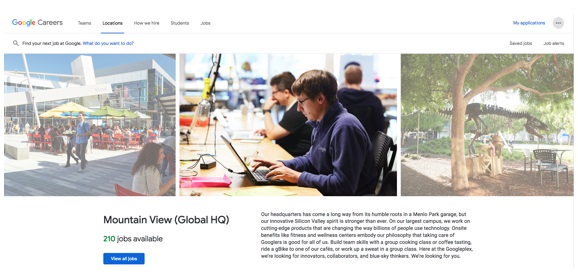

Figure 1: A google ad for jobs at the Googleplex. Source: https://careers.google.com/locations/mountain-view/?hl=en, accessed 11 July 2020

Figure 1 shows a typical Google

job-ad. It

advertises a variety of jobs such as software engineer, designer,

business

strategist, marketing, sales support, policy and privacy manager, etc.

in

Googleplex, the company headquarter in Mountain View, California.

Google in

this ad lauds itself for proving worker “[o]nsite benefits like

fitness and

wellness centers”, “a group cooking class”, “coffee tasting”, riding

“a gBike

to one of our cafés”. The business philosophy is that “taking care of

Googlers

is good for us all”. The point is that these benefits that promise

fun,

relaxation and entertainment are “onsite”: They keep Googlers at the

Google

premises and turn leisure time into labour time. When workers attend

yoga and

fitness classes, cooking classes, cafés etc. at the workplace, then

the

reproduction of their labour-power takes place at the workplace so

that there is

no clear spatial and temporal demarcation of labour time and

relaxation. The

three images in the job ad symbolise the blurring of space and time at

Google:

coding, chatting with colleagues in a café, a and relaxation in a

garden are

presented as integral parts of work at Google. Googlers do not leave

the

workplace for leisure time, but stay at the Google workplace. They

blurring

boundaries between workspace and playground and between worktime and

leisure-time result in an increase of unpaid labour-time. For Google

workers,

lifetime becomes Google time and value-creating labour-time. What

Google means

by saying that “taking care of Googlers is good for us all” is that

providing a

playful work environment is a method of exploitation by absolute

surplus-value

production that is good for Google’s profits.

4.6.

Precarious

Platform

Workers

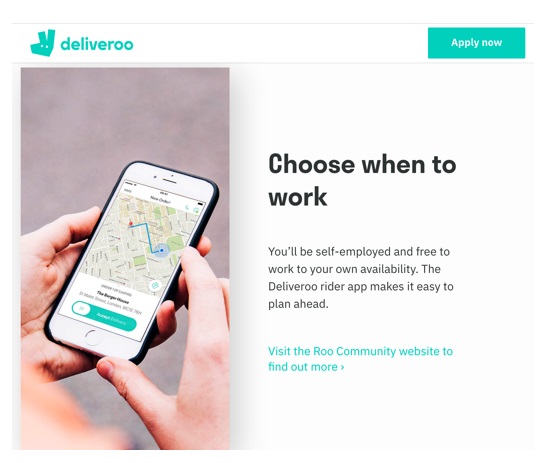

Digital capitalism has also given rise to platform workers. These are workers who mostly are freelancers and use apps and Internet platforms for finding work. Examples are the Uber and DiDi taxi driver, the Deliveroo biker who delivers food, and the online freelancer who uses platforms such as Fiverr, Upwork, or Freelancer for finding work. All of these platforms have in common that they are large capitalist corporations that own a proprietary software programme that platform workers use in order to find customers. The platform is a key means of production that is privately owned by digital corporations. Without access to this platform, the freelancers cannot find customers. They depend on this means of production. Formally speaking they are self-employed, but in reality they are workers who are exploited by digital platforms that control the key means of production as private property and capital. For each service organised via the platform, the capitalist platform corporation typically charges a share of the service price. It makes profit by renting out its platform to freelancers who produce a service commodity that is sold to customers that are found via the platform’s algorithms. Platform capitalists typically advertise their platforms as enabling flexible work that allows workers to earn lots of money. Figures 2 and 3 show two examples.

Figure 2: Deliveroo’s self-presentation as platform that enables

workers’

freedom. Source: https://deliveroo.co.uk,

accessed 11 July 2020

Figure 3: Uber’s self-presentation as platform that enables workers’ freedom. Source: https://www.uber.com/at/en/drive/, accessed 11 July 2020

The common narrative of these

self-presentations is that freelancer platforms enable and support

workers’

freedom to be their own boss and determine their work times

themselves, and in

doing so earn lots of money. The reality is that platform workers are

very

often highly exploited, precarious workers who work long hours to

survive (see Fuchs 2021, chapters 11 & 12;

Fuchs

2017b, chapter 10).

Platform workers are often piece-workers. They are not paid by the hour,

but for each completed service, each piece of work. Karl Marx (1867)

dedicates chapter 21 in Capital Volume 1 to piece-wages (see also Fuchs

2016,

chapter 21). He characterises piece-work and piece-wages as the

most

fruitful source of reductions on wages, and of frauds committed by the

capitalists” (Marx 1867, 694). Platform labour

is a

contemporary form of piece-labour and piece-wages in digital

capitalism that

aims at platform capitalists’ reduction of investment costs for

maximising

profits. If platforms such as Uber had to pay its drivers per hour, it

might

make much less profit than it does when charging a percentage share of

the

piece-price. Platform capitalism is a dimension of digital capitalism

that advances

highly precarious labour.

In CWCE, Engels describes the

working conditions of needlewomen, who were paid per piece. They were

low-paid

and conducted highly tiresome labour. “With the same cruelty, though

somewhat

more indirectly, the rest of the needle-women of London are exploited.

The

girls employed in stay-making have a hard, wearing occupation, trying

to the

eyes. And what wages do they get? I do not know; but this I know, that

the

middleman who has to give security for the material delivered, and who

distributes the work among the needle-women, receives 1½d. per piece”

(CWCE, 218). In digital

capitalist society,

transnational digital corporations such as Uber, Deliveroo, Fiverr, or

Upwork are

the contemporary middlemen that exploit digital pieceworkers.

4.7.

Labour

in

the COVID-19 Crisis

The 2020 COVID-19 crisis has

resulted in

radical changes of society and the economy. In many countries,

societies were “shut down” in order to

lower the infection risk. Many people stayed at home and worked from

home. The

economy and society thereby underwent substantial changes (Fuchs

2020b). Working at a physical distance mediated by

Internet-based

communication and co-operation technologies became widespread. Many

knowledge

and service workers, who normally conduct their work face-to-face in

offices,

started working at a distance from home. Workers such as academics,

teachers,

general practitioners, engineers, lawyers, consultants, artists, etc.

became

digital workers, who conduct services at a distance from their homes.

Their

homes became a supra-locale where working life, private life,

education,

leisure, etc. converged (Fuchs 2020b).

In the coronavirus crisis, being a digital worker who can work from home

is a privilege that reduces the risk of unemployment, illness, and

death. Other

workers, especially those in the tourism industry, personal services,

the

hospitality industry, and the culture and entertainment industry, who

cannot

conduct their services from a distance, lost their jobs. Key sector

workers

such as food workers, supermarket workers, or health care workers, who

work in

industries that are absolutely essential for society, couldn’t work

from a

distance and a shutdown of these realms of work was impossible.

Because of a

lack of personal protective equipment, workers in key sectors faced a

much

higher risk to get infected by and die from COVID-19.

Amazon’s online shopping business boomed during the coronavirus-crisis.

In the first financial quarter of 2020, its revenues increased from

59.7

billion US$ from the same period in 2019 to 75.5 billion, which is an

increase

by 26.5 percent[3].

Amazon’s stock price increased from US$ 1,900 US-dollar at the start

of 2020 to

US$ 3,200 in the middle of July 2020[4].

Amazon is the world’s 22nd largest transnational

corporation with

annual profits of US$ 10.6 billion in 2019[5].

In 2020. Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos was with a total wealth of

US$ 113

the world’s richest person[6].

Amazon workers are precarious service workers who according to reports

faced

the risk of getting infected by COVID-19:

In order to meet the demands of a country in which homes must suddenly be retrofitted to accommodate classrooms, co-working spaces, gyms, hair salons and so on, Amazon announced last month that it would hire 100,000 additional workers in its fulfillment centers and delivery networks, jobs for which many people will be desperate, given the decimated state of the retail and service industries. […] Though the company has increased pay by $2 an hour, employees around the country at Amazon warehouses and its subsidiary, Whole Foods, have been staging walkouts to demand better health protections during the pandemic. For years, Amazon has resisted the efforts of organized labor. […] In a letter to Mr. Bezos, […] labor leaders also addressed concerns that conditions at Amazon warehouses were unsafe: workers there were ‘reporting crowded spaces, a required rate of work that does not allow for proper sanitizing of work spaces, and empty containers meant to hold sanitizing wipes’. […[ various colleagues coming to work […] [were] unwell: fatigued, lightheaded, nauseous […] Later in the month, one of his colleagues, Barbara Chandler, tested positive for the coronavirus. She was advised by those in human resources at the facility to keep the news on the ‘down low’,’ she told me. Frustrated by what he perceived as the company’s lack of transparency, Mr. Smalls made it his mission to disseminate information about cases of Covid-19 at the warehouse (Bellafante 2020).

Amazon workers in countries such as

the USA,

France, and Italy protested against these conditions. Amazon has not

released

data on the number of its workers that got infected and the number of

those

that died. In the Amazon warehouse in Shakopee, Minnesota, 88 out of

1,000

employees got infected within 70 days (García-Hodges,

Kent

and Kaplan 2020).

Tönnies

Holding is

a German meat processing corporation that has more than 16,500

employees and.

Its headquarters are in Rheda-Wiedenbrück,

a

town in the German state of North

Rhine-Westphalia, where the company also operates a large meat

processing

plant. In 2018, the company achieved annual revenues of 6.65 billion

Euros[7]. In 2020, the wealth of

Clemens Tönnies and Robert Tönnies, who are the two major owners the

Tönnies

Holding, was US$ 1.8 billion each, which equally placed them as the

world’s 1196th

richest persons in 2020[8]. In summer 2020, there

were more than 1,500 COVID-19 cases among workers in the Tönnies

factory in Rheda-Wiedenbrück,

among them many low-paid migrant workers

who are bogus self-employed and live in crowded accommodations.

The agglomeration of workers in crowded spaces played a role in the

spread of COVID-19 among Tönnies-workers. A report in Der Spiegel describes the conditions that the predominantly Eastern

European Tönnies-workers faced in Rheda-Wiedenbrück:

They tend to be hired by subcontractors, they are poorly paid, quickly replaced and inadequately protected – even during the current coronavirus pandemic. […] Now, Clemens Tönnies – sometimes referred to as the Pork Chop Prince or the Meat Baron – has a problem. For years, he has ruthlessly pursued efficiency, but now, the entire country wants to know what goes on behind his factory gates. He has perfected the art of extracting all he can out of both his employees and the animals they process, transforming living creatures into an industrial product. His strategy was volume, volume, volume and he cut his costs to the bone, becoming the favorite supplier to Germany's discount grocery chains. The company enjoys a 30 percent share of the pork market in Germany. […] A Polish worker in Rheda-Wiedenbrück has a bit more to say, though he is fearful of speaking openly. He says he earns 1,600 euros for 190 hours of work per month. His shifts begin at 3 a.m. and end at 1 p.m., with a 30-minute break every three hours. ‘We stand at the conveyor belt about 20 to 30 centimeters apart, right next to each other. Often, the speed of the belt is ratcheted up and the supervisor watches us closely’. […] Like the Romanians in the white-plastered house near Münster, many workers aren't actually Tönnies employees, instead working for subcontractors, and without them […] According to Tönnies Holding, 50 percent of its workers are actually employees of such a company (Becker et al. 2014, 10-11; 11; 14)

Romanian

Tönnies

workers described the housing conditions they faced:

Romanian

worker: “It

was always very crowded; there were sometimes 10, 12, occasionally even

14

people in one apartment. The monthly rent was 200 euros each. The

buildings

belonged to the subcontractors. […] But it just isn't fair to cram so

many

people into one apartment!” (Deutsche

Welle 2020a)

Most workers interviewed, many of whom were very upset, have been either employed by the huge meat producer Tönnies or its subsidiaries. They have described extremely exhaustive work and aggressive language. The workers accused managers of not putting enough protective measures in place in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some have also said that the shared accommodation, in which they were forced to live, was cramped and inhumane” (Deutsche Welle 2020b).

In CWCE, Engels introduces the notion of social murder, by which he means poor working conditions that endanger the lives of workers. Social murder means that workers die “indirectly, far more than directly” (CWCE, 38) through social structures that cause the death of workers and that “society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live ” (CWCE, 106). Capitalism places

the workers

under

conditions in which they can neither retain health nor live long; that

it

undermines the vital force of these workers gradually, little by little,

and so

hurries them to the grave before their time. I have further to prove

that

society knows how injurious such conditions are to the health and the

life of

the workers, and yet does nothing to improve these conditions. That it knows

the consequences of its deeds; that its act is, therefore, not mere

manslaughter, but murder (CWCE, 107).

CWCE’s second chapter “The Great Towns”

focuses

on spatial conditions of working class life. It is an analysis of

everyday

urban life. Engels described how in English working class districts

“many human

beings here lived crowded into a small space” (CWCE, 39)

where there is “little

air – and

such air!” to breathe (CWCE, 65). 175 years after

Engels published

CWCE in 1845, poor working conditions and the racist exploitation of

migrant

workers have in the COVID-19 crisis created new forms of social

murder where

workers cannot keep social distance and working conditions result in

COVID-19

that makes it hard for infected poor workers to breathe and results

in the

death of a specific share of those who caught the virus.