1.

Introduction

In a chilling investigative account of what he aptly terms the “The Trauma Floor”, Newton (2019) describes terrifying details of the secret lives of Facebook content moderators. As a part of their daily labour regimen, they review hours of murder, hate speech, rape, and other forms of violent content for the leading social media website. In sharp divergence with the congenial imagery celebrated by the mainstream as making “Facebook the best place to work at” for its regular employees (Gillett 2017, 2), interviews with crowdworkers reveal a distinctly contrasting picture. These workers refer to their work as “mind-numbing”, “stressful”, “alienating”, “precarious”, and “micro-managed” and themselves as “bodies in seats” (Newton 2019, 24). Facebook’s regular employees, on average, make $240,000 per annum, enjoy premium health insurance, desirable retirement plans, and other perks. Crowdworkers for the same company, in contrast, survive on $28,800 a year without any benefits. They are part of a concealed global workforce that is unable to meet “elementary subsistence requirements”, is “constantly in search of work”, and works at “odd hours of the day” (Berg et al. 2018, 13). They are, as Roberts (2019, 201) persuasively argues, the miserable others of “digital humanity”.

Facebook is not the only global corporation benefitting from the misery of these workers. As a growing body of evidence from critical journalistic accounts, scholarly reports published by mental health professionals (Bourke and Craun 2014), legal experts (Cherry 2016), and labour surveys (Berg et al. 2018) reveal, digital giants such as Alphabet (Google and YouTube), Amazon, and numerous others are complicit in the exploitation of a concealed global workforce that experiences exploitation, job-insecurity, unemployment, and severe mental health issues due to the precariousness of their contracts on the one hand, and the repulsive nature of their work on the other. In oral narratives, workers describe “telling dark jokes about committing suicide”, “smoking weed during breaks to numb their emotions”, and “having sex inside stairwells” in what one worker describes as “trauma bonding” (Newton 2019, 68).

Despite the 175 years that separate them, an analysis of these oral accounts reveals a haunting resonance with the debilitating working conditions chronicled by Friedrich Engels in his seminal work The Conditions of the Working-Class in England (CWC):

They are exposed to exciting changes

of mental condition, the most violent vibrations between hope and

fear; they are deprived of all enjoyments except that of sexual

indulgence and drunkenness, are worked every day to the point of

complete exhaustion of their mental and physical energies. And if

they surmount all this, they fall victims to the want of work in a

crisis (Engels 1845, 396).

In

recent years, a number of scholarly contributions have posited

digital labour as a new historical form of human activity (Fuchs

and Sandoval 2014; Burston,

Dyer-Witheford and Hearn 2010; Fuchs

and Dyer-Witherford 2013; Fuchs

and Sevignani 2013; Scholz 2012; Azhar 2020). In a series of contributions,

Christian Fuchs (2007; 2013a; 2013b; 2014; 2015; 2017a; 2017b) elaborates concrete mechanisms

via which the mode of capital accumulation on Internet-based

platforms is premised, much like their industrial predecessors, on

the exploitation of human labour. Scholars also point to the broader

structural characteristics of the neoliberal economy – decades of

austerity, inequality, and wage-repression – leading up to, and in

the aftermath of, the Great Recession of 2007 that diminished the

bargaining power of workers, pushed them to accept precarious forms

of labour, and enabled new contractual forms of global accumulation

(and its corollary, worker’s exploitation) to emerge (Van

Doorn 2017; Hill 2017; Mahmud 2012; Peck

and Theodore 2012; Peck

and Tickell 2002).

This paper lies in the same research trajectory and seeks to contribute to explorations in digital capitalism by proposing a political-economic framework that draws on the pioneering work of Engels to understand the working conditions of platform laborers. I rely on a host of sources including quantitative/qualitative surveys conducted by the ILO and other organizations across multiple countries, scholarly work published in medical and legal journals, and oral narrations of workers recorded in journalistic accounts. The paper argues that four qualitative attributes of working conditions identified in the CWC are crucial for a theoretical appreciation of the lived experiences of contemporary digital labourers:

1) the link between enabling technologies and emerging forms of contractual, managerial, and social relations of production;

2) the upscaling of global competition within the working-class; what Engels describes as inter-worker competition;

3) a gendered and racial articulation of labour extraction that preys on the most helpless segments of the globe;

4) the broader attributes of the capitalist economy in the aftermath of the Great Recession that expanded the “surplus population”, its ties with the bargaining power of labour, and how it facilitated the birth of new forms of control and command structures.

The

CWC refers to these

dimensions as “the characteristic features of the development of the

capitalist mode of production” and its “inevitable consequences” for

workers (Engels 1845, 372). Following the dialectical

methodology proposed in Engels (1878),

I argue that the aforementioned dimensions can be seen as qualitative attributes that have witnessed quantitative transformation since Engels’s time. Thus, despite the

spatial-temporal distance that separates industrial England from

contemporary digital labour, the core features and outcomes remain

strikingly similar to the framework proposed in the CWC.

The paper focuses on a narrow set of digital workers, specifically, the class of “crowdworkers”: contingent workers that perform contractual “on-demand” labour on digital platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT), Clickworker, CrowdFlower, Microworkers etc. Crowdworkers are large groups of workers that are peculiar in a number of ways. They find and perform labour online, span multiple time zones, and essentially work on piece-rates; that is, they do not have contracts beyond the single task at hand. Their exploitation is concealed behind the legal facade of “self-employment”.

A focus on a subset of digital workers is justified on two grounds. First, as Fuchs and Sandoval (2014) point out, there is a multiplicity of possible forms of digital labour. To complicate comparative analyses further, the supply chains within which these differential forms are embedded may coexist alongside non-capitalist relations (Fuchs 2017a). Consequently, which forms fulfil the key characteristics of digitality is itself an open empirical/theoretical question, an answer to which depends on “various dimensions of work, such as the way people look for jobs and employment, employer’s search for labour power, the relations of production, the technological means of production, the used resources, the created products, forms of distribution, and forms of consumption” (Fuchs and Sandoval 2014, 514). By focusing on a subset, we can fix the dimensions of employment-search, the managerial model (algorithmic management), the technological infrastructure, and the contractual relations within which the labour process occurs.

Second, focusing on a subset of digital labourers allows an analysis of both the similarities as well as the diversity within working conditions along gendered and national lines. A key concern for Engels in the CWC, an aspect to which he devotes an entire section of the book, is to unearth mechanisms via which fractures and competition within the working-class impacts general working conditions. Seen from this light, platforms are the “closest proxy to the idea of a global labour market where everyone competes for jobs regardless of location” (Beererpoot and Lambregts 2015, 236) and provide us with an ideal setting to re-examine Engels’s key predictions.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: section 2 briefly revisits four key theses from the CWC. Section 3 utilises this theoretical scheme to examine working-conditions on crowdplatforms using a host of empirical sources. Section 4 concludes with a discussion of the implications of revisiting the CWC for critical theory and praxis in the digital world.

2.

Theoretical: CWC as a General Theory of Capitalist

Working Conditions

I am up to my eyebrows in English newspapers and books upon which I am drawing for my book on the condition of the English proletarians. I shall be presenting the English with a fine bill of indictment; I accuse the English bourgeoisie before the entire world of murder, robbery, and other crimes on a massive scale […] That’ll give those fellows something to remember me by (Engels 1844, 10)

This section briefly revisits the CWC as a theory of working conditions under capitalist relations of production; specifically, as a framework that ties the technological infrastructure in any capitalist setting to a theory of the lived experiences of the working population that sustains it. Engels connects technical innovations to specific contractual and managerial modes of exploitation, delineates the gendered and racial articulation of labour extraction via the concept of inter-worker competition, and also examines the dynamics of “surplus population” that propel workers to participate in precarious labour. In the next section, we will use this framework along with recent extensions by Fuchs and Sandoval (2014) to contextualise empirical accounts of crowdworkers.

2.1.

Technology, Competition, and Social Relations

The consequences of improvements in machinery under our present social conditions are, for the workingman, solely injurious, and often in the highest degree oppressive (Engels 1845, 433)

The CWC presents distinct channels via which technological developments, fettered by capitalist social relations, adversely impact the conditions of a given working population by:

1) expanding inter-worker competition, that is, by transforming the scale at which workers compete against one another;

2) giving birth to unique contractual and managerial bonds that disguise the dichotomy between paid/unpaid labour via the facade of legality;

3) deskilling workers due to task monotony and the constant threat of being pushed into the ranks of the unemployed, what Engels terms a “surplus population” (Engels 1845, 566). Each of these factors will be clearly observed in the oral narrations of crowdworkers in section 3.

2.1.1.

Inter-Worker Competition

A key prediction in the CWC is that an expansion in the global labour market will exert a downward pressure on wages by enhancing inter-worker competition. “Competition”, Engels argues, “is the completest expression of the battle of all against all which rules in modern civil society” (Engels 1845, 375). It as a “battle for life” that is “fought not only between different classes of society alone but also within the individual members of these classes” (375). Thus, the scale of inter-worker competition determines the “minimum of wages” and the concept is central to any account of working conditions (375).

2.1.2.

Labour Contracts and Managerial Relations

Another qualitative attribute of the CWC is to theorise the technological apparatus in any capitalist setting in relation to the contractual and managerial relations that it engenders. Engels argues that these juridical relations are pivotal to an understanding of working-conditions as they determine the precise manner “in which the bourgeoisie holds the proletariat chained” (467). The domain of the contract, he argues, is where “ends all freedom in law and in fact” (467). This will be an important theme when trying to understand the legal underpinnings of crowdworkers’ struggles against digital capitalists in the next section. As we will see, the platform-owner is akin to “the “absolute law-giver”; he makes “regulations at will, changes and adds to his codex at pleasure, and even, if he inserts the craziest stuff, the courts say to the working-man: “You were your own master, no one forced you to agree to such a contract!” (467).

2.1.3.

Surplus-Population and Worker’s Bargaining Power

Engels also pays close attention to the role of technological change in determining the unemployment rate and the bargaining power of labour. His analysis points to the structural attributes of the capitalist economy at any given point and how these, in turn, propel workers to pursue precarious labour: “anarchy of production”, “period crises”, “deepening of class antagonisms”, and “the formation and growth of a reserve army of labour and chronic unemployment” (Engels 1845, 444-452).

2.2.

Nationality and Gender

In addition to theorising the technological infrastructure in relation to working conditions, the CWC is one of the first scholarly attempts to theorize the disparities within the conditions of the working class along the lines of nationality and gender. This includes an analysis of identity-based sectoral employment and the net impact of these differences, in turn, on aggregate working-conditions.

Technical innovations of the industrial era had already begun to incorporate “the vast masses who now fill the whole of the British Empire” (Engels 1845, 351). Prior to this, the “crushing power of competition that came later with the conquest of foreign markets and the extension of trade did not yet press upon wages” (351). At the global scale therefore, Engels argues, the internal transformations in Western capitalism and their impact on the working-class need to be seen in their interconnectivity with the periphery, the broader colonization movement at the time (Magubane 1985).

Engels devotes a section to “Irish immigration” to understand variations in relative depravity across nationalities. “The Irish”, Engels argues, “had nothing to lose at home, and much to gain in England” (Engels 1845, 388). They were willing to accept the “minimum of the necessities of life” (390). British capitalists benefitted enormously from the “impoverished population of Ireland”, which acted as “a reserve army at their command” (389). Engels’s prediction is that the scale of international inter-worker competition is inversely related to working conditions, as it allows capitalists to extract maximum surpluses by targeting the most helpless sections. A befitting confirmation of this prediction will be seen in the next section when considering how crowdplatforms use programmed filters to target particular sections of the global working-class. This will be crucial to appreciating wage-differentials between crowdworkers in the global North versus third-world countries.

Finally, a consistent theme in the CWC is the gendered articulation of capitalist exploitation. Engels points out that the wage-differential along gendered lines is also intricately tied to the concept of inter-worker competition. On the one hand, technological changes allow capitalists to replace male workers with female workers. But the exploitation of women, Engels points out, takes an even more “inhumane form” owing to the additional burden of child-care. The exploitation of both parents “at once breaks up the family”; the children “grow like wild weeds” (Engels 1845, 436) bringing the most “demoralizing consequences for parents as well as children” (437). As we will see, many female crowdworkers will point to their care responsibilities as a dominating factor effecting their working conditions.

3.

The “Others” of Digital Labour: Class, Gender, and

National Exploitation on Crowdwork Platforms

We now turn our attention to contemporary crowdworkers and ask whether or not, and to what extent, their experiences bear “the characteristic features of capitalism” and its “inevitable consequences” (Engels 1845, 355). Following Engels’s mode of presentation in the CWC, I begin by describing the technological infrastructure (crowd-platforms) and how it enables a new managerial and contractual labour-extraction model. We then turn to the dichotomy of paid and unpaid work on platform technologies, the national and gendered variation across the experiences of crowdworkers, and finally the conceptual framework of “surplus population” as an explanatory tool for why workers engage in crowdlabour despite the precariousness that it offers. At each stage, worker’s oral narratives are carved into the theory to demonstrate the experiential validity of Engels’s predictions. To do this, we will rely on two broad sources of information:

1.

Survey

data

collected by the ILO and other organisations across multiple

countries in two recent surveys (2017 and 2015)

2.

Qualitative

information

from oral narrations of workers and scholarly accounts published

in legal and medical studies.

3.1.

Crowdplatforms: Algorithmic Management and

Concealed Exploitation

“It’s a precarious employment situation as you’re entirely at the mercy of the crowdwork platform” – Worker on the platform CrowdFlower, United Kingdom (Berg et al. 2018, 73)

“This is obviously a way of working that will likely explode in the future” – Worker on the platform Amazon Mechanical Turk, United States (Berg et al. 2018, 1)

The birth of the Internet led to the emergence of a unique labour process that could be performed on a new technological infrastructure, the crowd-platform, via which capitalists engage in a transitory, piecewise, and anonymous relationship with a geographically segregated global workforce that is, quite revealingly, referred to as the “crowd”. Value creation revolves around a platform-mediated online interaction between crowdworkers and service-requestors, where the latter “advertise tasks to large numbers of potential workers” and then use the platform to “retrieve and evaluate the results of completed tasks” (Berg et al. 2018, 11). The anonymity and transitory nature of the relationship offers capitalists the ability to control a contingent workforce with the additional facility of disguising exploitation using layers of contractual legalities. Mainstream theorists describe a platform as a “business that connects external producers and consumers and enables value-creating interactions between them” (Choudary 2018, 1). Seen from this light, the platform is nothing more than an intermediary between a producer and a consumer, rather than a power arrangement between a capitalist and an employee.

But a more nuanced political-economic understanding of the links between the mode of accumulation, corresponding relations of production, and working-conditions can be developed by paying closer attention to the labour-control mechanism. As the CWC explains, technological developments are fettered by capitalist relations and must be seen as institutions of monitoring and control. The unique attribute of crowd-platforms, from the capitalist standpoint, is not their ability to facilitate interactions but rather to create a governance model where capital can control workers while concealing labour exploitation.

Fuchs and Sandoval (2014) extend Engels’s framework by presenting a convenient classification scheme that can be used to analyse working conditions under any capitalist production process. Using Marx’s circuits of capital approach (Marx 1867), they present a model that delineates five distinct factors jointly shaping working conditions throughout any capital accumulation process.

The circuit describes the different “moments” of capital accumulation; at the first stage, the initial M is spent on the commodities necessary for production: means of production (MOP) and labour-power (L). In the second stage, it enters the sphere of production (P) where these commodities are productively consumed, giving birth to a new commodity (C’) that is pregnant with surplus-value. In the final phase, this surplus-value is realized with the sale of the commodity and its reconversion to the money form (M’).

Seen from this light, the platform is the institutional and infrastructural arrangement that sets the conditions for production, exchange, and the remuneration of labour-power. It is at once the site of productive labour processes (the moment P), the mode via which workers exchange their labour-power for money (L-M), and the unique managerial model that adjudicates whether the output (C’) is acceptable to the service-requestor or not.

A key attribute of the technology is the manner in which it arbitrates disputes between the task-requestor and the worker: “algorithmic management”. In essence, workers are supervised by an algorithm that controls the labour process, the worker’s output, and the piece-rate remuneration. In contrast to the claims by corporations that the method ensures “neutrality”, the algorithm is actually designed to punish the slightest of errors on the part of workers.

This fact is borne out clearly in worker’s accounts. For example, McInnis et al. (2016) who study the platform used by Amazon – Amazon Mechanical Turk – find that the number one complaint by crowdworkers is “work rejection” (McInnis et al. 2016, 2271). “Unfair rejections”, workers explain, “can result from poorly designated tasks, unclear instructions, technical errors, and malicious requestors” (2271). Algorithmic management implies that “dispute resolution between workers and employers becomes intractable” (Irani 2013, 614) since there is no way workers can dispute the decision of the algorithm.

The algorithm is pre-programmed in a way that the service-requestor has the final word in every dispute. As Irani (2015, 228) explains, “Amazon does not require requestors to respond and many do not”. Consequently, workers never know the reason why their work has been rejected. This explains why 90 percent of workers in ILO surveys “have had work rejected or have had payment refused” without recourse or right to appeal (Berg et al. 2018, 74). As a worker aptly explains, “if a requestor decides to reject your work, there is no way to contest this and have them make a fair ruling” (76). Another crowdworker for the platform Prolific explained that “you can be fired without notice, reason, or appeal” (82).

Engels’s notion of the contractual bond, as a force that legalises misery, is vividly observed in workers’ accounts. Before accepting a task, workers must agree to certain terms and conditions. As a rule, most platform owners make workers accept the status of an “independent contractor”. For example, the conditions set by Amazon clearly state that “workers perform tasks for requesters in their personal capacity as an independent contractor and not as an employee of a requestor or Amazon Mechanical Turk” (Amazon Mechanical Turk 2017). Inequality is coded into law; the terms make it absolutely clear that crowdworkers “are not entitled to any of the benefits that a Requestor or Amazon may make available to its employees, such as vacation pay, sick leave, and insurance programs”. Most crucially, workers are not “eligible to recover worker’s compensation benefits in the event of injury” (Amazon Mechanical Turk 2017). Other platforms, such as Prolific, do not even classify them as workers of any kind, instead describing them as “participants” in research projects who receive “rewards” rather than payment for work performed (Prolific 2020).

As Engels would expect, the managerial and contractual model has been the subject of intense legal battles between workers and capitalists. Cherry (2016) conducts a comprehensive survey of recent disputes and their implications for labour regulations in the digital age. As her analysis reveals, disputes largely revolve around the contractual misclassification of workers. Despite the optimistic claims of celebrants, who brush aside the issue beneath the ideological facade of the “sharing economy”, these legal battles reveal a close proximity to Engels’s predictions. As Cherry (2016, 570) argues, “the new crowdwork seems a throwback to the de-skilled industrial processes” but “without the loyalty and job security”. For example, in one class action lawsuit, Otey vs CrowdFlower, platform owners contended that since workers had contractually agreed to the terms of “self-employment”, they did not have the right to demand a minimum wage (Cherry 2016). In another lawsuit, filed against Microsoft by Soto and Blauert, workers complained that the terms and conditions “did not prepare them for the stress of the job, nor did it offer adequate counselling and other measures to mitigate the psychological harm” (Cherry 2016, 566).

3.2.

Paid, Unpaid Labour, and the Delusion of

Flexibility

Crowdwork platforms advertise their tasks by promising flexibility and autonomy with regard to the “amount of work, the work schedule, and the location” (Berg et al. 2018, 49). An alternative reality, however, is revealed in worker’s narrations who complain that their work is micromanaged, underpaid, monotonous, and alienating. As one Serbian worker for the platform CrowdFlower put it “a worker doesn’t have much rights; very little if any worker protection, because everything is organized for the interest of the people that are hiring us” (Berg et al. 2018, 59).

Crowd-platforms allow capitalists to undercut domestic minimum wage regulations and prey on the most helpless sections of any country. This fact is borne out most visibly in ILO surveys, which distinguish between time spent doing paid work (i.e. actual work tasks that the crowdworker was paid for) versus the time spent doing unpaid work (i.e. looking for tasks, earning qualifications, unpaid/rejected tasks). The data reveals that a crowdworker spends “24.5 hours doing crowdwork, of which 18.6 hours are paid work and 6.2 hours unpaid” (Berg et al. 2018, 67). In other words, every hour of paid work implies that a third of additional time must be spent performing unpaid tasks. On average, “a worker earned $4.43 per hour when only paid work is considered, and if total paid and unpaid hours are considered, then the average earnings drop to $3.31” (Berg et al. 2018, 49). In another quantitative study, Hara et al. (2018) conduct a task-level analysis of 2676 workers performing 3.8 million tasks for Amazon and find that on average their crowdworkers earn approximately $2/hour and only a tiny proportion, roughly 4%, earn the minimum wage $7.25/hour.

Moreover, across all 75 countries surveyed by the ILO, an overwhelming number of workers earn below their national minimum wage. For example, in 2017 on Amazon Mechanical Turk, roughly 48 percent of American workers earned less than the federal minimum wage ($7.25) when only paid work is considered, and these proportions increase to 64 percent when unpaid work is taken into account (Ibid; 50). As one worker for AMT aptly pointed out: “a bare minimum of 10 cents a minute is barely acceptable, but anything under that is just greed” (Berg et al. 2018, 56).

As Engels would expect, the subhuman remuneration of these workers is intricately tied to their poverty. On average, 20% of crowdworkers surveyed by the ILO live in a household that cannot meet its basic subsistence requirements. The percentage of workers from a household that has insufficient savings to cover an emergency equal to one months’ income is even larger, at 42 percent (Berg et al. 2018, 59). 44 percent of households “have debts such as student loans, car payments, medical or legal bills, or loans from relatives” (59). Moreover, the illusion of “flexibility” immediately appears as a facade when considering that a fifth of the workers surveyed by the ILO in 2017 reported that “they had current physical or mental health conditions lasting 12 months or more” (39). Quite significantly, 54 percent of these workers reported that their health problems affect the “kind of paid work they might do” (39).

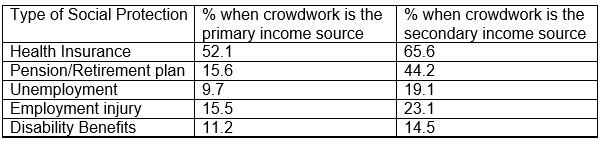

Yet, unless covered by another job, most crowdworkers surveyed by the ILO did not have access to social security benefits: barely 40 percent had access to health insurance, less than “35 percent had a pension or retirement plan, merely 37 percent benefitted from some form of social insurance”, and less than a third of the workers received government assistance (Berg et al. 2018, 60). As Engels’s notion of the inverse link between a worker’s bargaining power and remuneration would predict, Table 1 reveals that social protection coverage is inversely related to an individual’s dependence on crowdwork; only 16 percent of the workers for whom “crowdwork is the main source of income were covered by a retirement plan, compared to 44% of those for whom crowdwork was not the main source of income” (60).

Table 1: Social Protection and Reliance on Crowdwork (Source: Berg et al. 2018)

3.3.

National and Gendered Differences

“Work should not be racial. It should be distributed equally in all the places rather than distributing it on the basis of country” – Worker on Microworkers, Nepal (Berg et al. 2018, 64)

“I have three children and don’t have the means for a babysitter” – Worker on Microworkers, United States (Berg et al. 2018, 69)

Mainstream accounts often posit crowd labour as a unique opportunity for third-world economies and housewives to make money in otherwise stagnant economies (Nickerson 2014; Schriner and Oerther 2014); as a “silver bullet” for development that provides the “best hope for providing employment” that “leverages the natural, inherent incentives embodied in capitalism” (Schriner and Oerther 2014, 224). Yet, the experiential reality of the global digital working-class reveals a sharply contrasting picture.

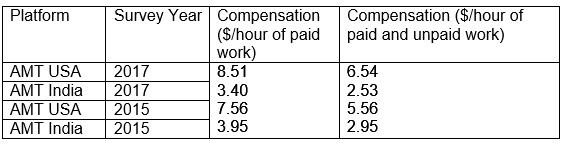

As pointed out earlier, a key attribute of the platform is the creation of a global online labour market (Beerepoot and Lambregts 2014). This offers capitalists the unique opportunity of accessing the most helpless sections of the global workforce through the use of filters. Most platforms allow “clients to choose whether the tasks will be done by the global pool of labour or by a specific population based on certain characteristics, such as geographic location, earned qualifications, or other filtering criteria” (Berg et al. 2018, 63). Table 2, which compares the average compensation of workers in the USA and India across the same platform, Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT), reveals that the average compensation for an AMT USA worker is two and a half times that of an Indian worker.

Table 2: Compensation across Nationalities (Source: Berg et al. 2018)

As Engels argued in the CWC, the greater the scale at which workers compete against one another, the lower will be the standard of overall wages and the differential within the working-class. The ILO survey befittingly confirms this prediction when it finds that in the “global competition for tasks on online platforms, the rivalry between American or European workers and workers in developing countries for the same tasks leads to a lowering of the equilibrium price for tasks” (Berg et al. 2018, 52). Workers in North America (US $4.7) and Europe ($3) earned significantly more than workers in Africa (US $1.33) and Asia Pacific (US $2.22). The share of crowdworkers living in poverty is “particularly high among crowdworkers in Africa (42 per cent), Asia (24 percent), and Latin America (23 percent)” (58) and lower in North America and Europe (17 per cent). Barely a fifth of crowdworkers from Africa and a third of workers from Asia had access to social benefits. The weakness of public social protection in these regions, in turn, implies that platform operators have “an additional incentive to undertake tasks using the pool of labour from these countries” as they face “less pressure from workers and governments to ensure social protection for platform workers” (61).

Moreover, national differences not only explain wage disparities but also the sectoral spread of the tasks assigned to workers from different nationalities. The tendency of increasing inter-worker competition identified by Engels is “reinforced by platforms that allow tasks to be targeted to specific groups of workers according to specific criteria, including country of residence” (Berg et al. 2018, 54). The tasks that are best-paid, such as “content-creation, editing, and content writing are often available only to American workers” (54). As Martin et al. (2014, 225) demonstrate in their ethnomethodological study of AMT workers, the crowd-platform labour market is akin to a “dual-banded labour marketplace” with national wage differentials programmed into the logic of the relation of production. Understandably, workers in the periphery have an acute awareness of this systemic bias. As a crowdworker for the platform Prolific in India pointed out, “just because someone is desperate enough to do these jobs doesn’t mean that you will literally pay them peanuts” (Berg et al. 2018, 56).

Quantitative studies also reveal sharp discrimination along the lines of gender. As Engels would expect, there are major differences between the care-giving responsibilities between men and women and this directly impacts the working-conditions of female crowdworkers. In the ILO surveys, women were thrice as likely as men to report that the primary reason why they engaged in this work was because they could “only work from home” (Berg et al. 2018, 38). As one female worker narrates, “traditional workplaces are not compatible with my current needs” (39). A fifth of the female workers surveyed by the ILO had small children (69). These women spend “on average about 19.7 hours working on platforms in a week”; 36 percent of these work at night (10 p.m. to 5 a.m.) due to child-care responsibilities, and 65 percent during the evening (6 p.m. to 10 p.m.). Yet, “accounting for unpaid work, women’s average pay was between 18 and 35 percent less than that of men” (52).

3.4.

Deskilling, Alienation, and Monotony

“In the beginning, I had hoped that I would also get some higher quality type of work [...] But that doesn’t happen. It is usually very simple, basic work. It is not really what I expected” – Worker for the platform Clickworker (Berg et al. 2018, 97).

“Crowdwork kept me from being homeless, but it’s also a curse” – Worker for AMT India (Berg et al. 2018, 83)

In the CWC, Engels posits an intricate tie between capitalist accumulation and worker’s alienation due to the deskilling effect of task-monotony. As far as capital is concerned, Engels argued, “if the monotony of an occupation makes you better suited for that occupation, then monotony is a productive force” (Engels 1845, 285). Consequently, “the worker’s activity is reduced to some paltry, purely mechanical manipulation, repeated minute after minute” (415). Oral narrations of crowdworkers provide a befitting confirmation of this prediction as well. Across a range of quantitative and qualitative studies, crowdworkers describe their work as “frequently repetitive”, “boring”, and “mind-numbing”. As one CrowdFlower worker put it, “It’s not the type of job that requires many skills […] besides knowing English” (Berg et al. 2018, 82). Another crowdworker from Germany, when asked for the reasons for her dissatisfaction, responded that “the work in itself is boring and physically tiring” (45).

While crowdworkers are generally well-educated, the repetitive and mundane nature of the tasks that they perform leads to severe underemployment and deskilling. The ILO found “no relation between the educational level and the type of task performed” (83). The most common tasks performed by workers were content access (46 percent), data collection (35 percent), responding to surveys and experiments (65 percent), and transcription (32 percent). These tasks “include creating fake user accounts on websites, clicking through pictures, or watching and liking/sharing a video” (85). As one AMT worker put it, “it’s a mind-numbing form of work” (96).

Content moderation, a major category of work, is particularly important for social media websites such as Facebook and YouTube that allow users to upload content. These tasks are often outsourced to crowdworkers, particularly in developing countries such as India and Philippines, who suffer from severe psychological trauma as a result of moderating repulsive content on repeat. Despite being well-educated, content moderators typically spend their days looking at content “” (Roberts 2016). As one former Facebook moderator succinctly explains: “Think like that there is a sewer channel and all of the dirt/waste/s*** of the world flows towards you and you have to clean it” (Chen 2017, 8).

The quantum of work performed is also quite significant, “as many as 8000 posts a day, rife with hate speech, videos of sexual exploitation, and violence” (Chen 2017, 8). As Engels would expect, the traumatic labour process takes a vicious toll on the mental health of crowdworkers. A study conducted by medical experts of the U.S Marshals Service, reported that a quarter of people in their sample “displayed symptoms of traumatic stress disorder” with frequent symptoms such as “insomnia, nightmares, anxiety, or hallucinations” (Bourke and Craun 2014, 587).

3.5.

“Surplus Population”: Macro Reasons for Undertaking

Crowdwork

As Engels reminds us in the CWC, the individual experiences of workers are embedded within the overall state of the capitalist economy at any point in time, specifically the unemployment rate. True, digital technologies made it feasible to organize labour processes of business models around crowdwork. But it is equally crucial to appreciate the reasons workers give in oral narrations for why they undertake crowdwork, despite the precariousness and volatility that it offers.

The “on-demand” business model would be inconceivable without the large “surplus population” that was released in the labour market via under- and unemployment in the aftermath of the global collapse of capitalism, that is, the Great Recession in 2007/08. (Hill 2017; Van Doorn 2017). The crisis itself, however, was a product of the decades of neoliberalism that preceded it. The historical stage was set by a host of reforms that resulted in a rapid decline in the organizational power of labour. As Peck and Theodore (2012, 742) point out, this allowed “temporary staffing agencies” to emerge as an industry in its own right, restructure “workforce systems and rewrite the social contract” governing employment so that employers could “download the risks inherent in a volatile economy and to offload the responsibilities that historically have been associated with the standard employment relationship” (742).

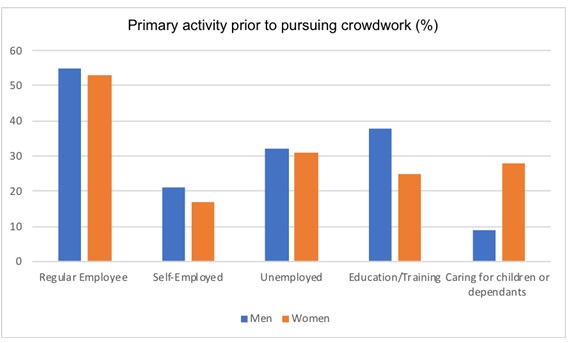

Engels’s notion of “surplus population” is aptly reflected in oral narrations. In an overwhelming number of cases, unemployment immediately precedes crowdwork. As the figure below reveals, prior to working as crowdworkers 55% of workers had been working as regular employees and over 30% were unemployed.

Figure 1: Activity prior to pursuing crowdwork (own image based on data source: Berg et al. 2018)

In mainstream narratives, crowdwork is generally posited as a source of secondary income. But this is true for only about a third of the workers, for whom the most important reason for performing crowdwork was to “complement pay from other jobs” (Berg et al. 2018, 37).Yet, as the ILO survey revealed “dependence on crowdwork was much higher than what was reported” (41). About 48 percent of the workers “were not engaged in any other type of employment” while an “additional 8 percent had another job but earned more from crowdwork than in the other job”, implying that “for 56 percent of the respondents the main income source was crowdwork” (41). Overall, 80% of workers surveyed reported that their wages were a substantial portion of their household income and roughly two thirds said, “it was necessary for meeting their basic needs” (41).

Finally, as the CWC explains, a perpetual feature of the lives of workers under capitalist relations is the element of obtaining the work itself. In the Industrial era, Engels points to the “hundreds of poor men” who could “be seen before daybreak in the hope of obtaining a day’s work” (Engels 1845, 385). Similarly, roughly nine out of ten workers surveyed by the ILO in 2017 responded that “they would like to do more work” (Berg et al. 2018, 39). Moreover, this experience had marked regional variations; 98 percent of workers in Africa, 91 percent in Asia, and 90 percent in Europe and Central Asia expressed this sentiment compared to 80 percent in North America. Overall, four in ten crowdworkers were “actively looking for paid work other than crowdwork” (66). A worker on the platform, Clickworker, pointed out that “the most frustrating part of crowdwork is waiting for work” itself (62). As Engels would expect, fettered by capitalist relations this aspect of working conditions also remains unhinged by the promise of digitality.

4.

Conclusion

A class which bears all the disadvantages of the social order without enjoying its advances, one to which the social system appears in purely hostile aspects – who can demand that such a class respect this social order? Verily, that is asking much! But the workers cannot escape the present arrangement of society so long as it exists, and when the individual worker resists it, the greatest injury falls upon himself (Engels 1845, 424).

The paper sought to reorient contemporary discussions of digital labour to Engels’s persuasive critique of working conditions under capitalism. It argued that an appreciation of the CWC is vital to our understanding of the lived experiences of contemporary crowdsourced labour. However, in addition to its theoretical relevance, revisiting the CWC also has crucial implications for political praxis on the Internet. It is worth recalling that many socialist thinkers, who Engels would later call “utopian Socialists”, had already written about the miserable conditions of the working classes. Engels’s distinction was to present the working classes not merely as a “suffering mass” but as a “revolutionary force” (Engels 1845, 433). As Lenin would note, the CWC was the first text to explicitly state that the “the disgraceful economic condition” of the worker propels “it irresistibly forward and compels it to fight for its ultimate emancipation” (Lenin 1895, 22).

However, a number of aspects will have to be adequately addressed before a global struggle of digital laborers becomes the political force that Engels envisioned. Contemporary critics of digital capitalism will have to pay closer attention, as Engels indeed did, to the differences within the digital working-classes by focusing on the diversity of social relations and economic circumstances that propel digital labour. Given Engels’s commitment to internationalism, theorists will have to zoom-into the demographic, gendered, class, and national specificities of digital labour processes. As digital surplus-value appropriation differentially impacts those that it exploits, a transnational exploitative regime calls for a multi-tiered collective praxis beyond national borders.

Moreover, revisiting the CWC to critically understand digital working conditions can also point towards a systematic rethinking of concrete forms of post-capitalist transformation in the digital era. In particular, platform cooperativism can “foster social change by creating a People’s Internet and replacing corporate-owned platforms with user-owned co-operatives” (Sandoval 2020, 801). These alternatives, in turn, could provide a befitting challenge to the exploitative regimes of the corporate sharing economy (Scholz 2016).

A return to Engels’s CWC will also be crucial in responding to critics who argue that Marxian critiques are tied to the industrial world. Revisiting the CWC will allow us to thoroughly debunk this myth and appreciate that while the appearance of labour processes has drastically transformed during the past two centuries, its content in terms of capital-labour relations, the exploitative micromanagement of worker’s lives, the gendered and racial dimensions of this exploitation, the helplessness that propels the worker, and the surplus-value enrichment of digital companies at the expense of workers remains inherently unchanged at its core. As in industrial England, long underpaid hours leave digital workers seeking refuge in drugs. Much like their industrial predecessors, the working conditions faced by digital proletarians are monotonous, misogynistic, and mentally debilitating and a return to Engels’s work remains crucial in carving a global collective response against it.

References

Amazon Mechanical Turk. 2017. Participation Agreement. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.mturk.com/participation-agreement

Azhar, Shahram. 2020. Consumption, Capital, and Class in Digital Space: The Political Economy of the Pay-per-Click Business Models. Rethinking Marxism. Accessed October 3, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2020.1750196

Choudary, Sangeet Paul. 2018. The Architecture of Digital Labour Platforms: Policy Recommendations on Platform Design for Worker Well-being. Geneva: International Labour Office. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_630603.pdf

Fuchs, Christian. 2015. Culture and Economy in the Age of Social Media. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Digital Labour and Karl Marx. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian and Marisol Sandoval. 2014. Digital Workers of the World Unite! A Framework for Critically Theorising and Analysing Digital Labour. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 12 (2): 486-563. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/549

Fuchs, Christian and Sebastian

Sevignani. 2013. What Is Digital Labour? What Is Digital Work?

What’s their Difference? And Why Do These Questions Matter for

Understanding Social Media? tripleC: Communication, Capitalism

& Critique 11(2): 237-293. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/461

Gillett, Rachel. 2017. Why Facebook is the Best Place to Work in America. Business Insider, December 7. Accessed October 1, 2020. www.businessinsider.com/facebook-best-place-to-work-in-america-2017-12

Mahmud, Tayyab. 2012. Debt and Discipline. American Quarterly 64 (3): 469-494.

Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital Volume I. London: Penguin.

Newton, Casey. 2019. The Trauma Floor: The Secret Lives of Facebook Moderators in America. The Verge, February 25. Accessed August 10, 2020. www.theverge.com/2019/25/18229714/cognizant-facebook-content-moderator-interviews-trauma-working-conditions-arizona

Peck, Jamie and Adam Tickell. 2002. Neoliberalizing Space. Antipode 34 (3): 380-404.

Prolific. 2020. Prolific Terms of Service. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.prolific.co/assets/docs/Researcher_Terms.pdf

About

the Author

Shahram

Azhar

Shahram Azhar is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Bucknell University. Research interests include political economy of digital capitalism and development economics.