Everyday Life and Everyday Communication in Coronavirus Capitalism

Christian Fuchs

University of Westminster, London, christian.fuchs@uti.at, http://fuchsc.net

Everyday Life and Everyday Communication in Coronavirus Capitalism

Christian Fuchs

University of Westminster, London, christian.fuchs@uti.at, http://fuchsc.net

Abstract:

In 2020, the

coronavirus crisis ruptured societies and their everyday life around the globe.

This article is a contribution to critically theorising the changes societies

have undergone in the light of the coronavirus crisis. It asks: How have

everyday life and everyday communication changed in the coronavirus crisis? How

does capitalism shape everyday life and everyday communication during this

crisis?

Section 2 focuses on how social space, everyday

life, and everyday communication have changed in the coronavirus crisis.

Section 3 focuses on the communication of ideology in the context of

coronavirus by analysing the communication of coronavirus conspiracy stories

and false coronavirus news.

The coronavirus

crisis is an existential crisis of humanity and society. It radically confronts

humans with death and the fear of death. This collective experience can on the

one hand result in new forms of solidarity and socialism or can on the other

hand, if ideology and the far-right prevail, advance war and fascism.

Political action and political economy are decisive factors in such a profound

crisis that shatters society and everyday life.

Keywords: coronavirus, COVID-19, everyday life,

everyday communication, critical theory, critical theory of communication,

means of communication, communication technology, capitalism, ideology, fake

news, false news, crisis, public health, Henri Lefebvre, David Harvey

The coronavirus-disease (COVID-19) is a highly infectious respiratory disease.

Its name stems from the fact that it looks like a crown under the microscope.

The virus is highly contagious and has a death rate that is multiple times

higher than the one of seasonal flu. Common symptoms include fever, a dry

cough, shortness of breath, and extreme tiredness. The majority of cases have a mild development, but in a certain

share of cases a severe pneumonia develops that can be life-threatening.

The first patient

suffering from the disease was identified on 1 December 2019 in Wuhan, a city

with more than 11 million inhabitants in China’s Hubei province. By the end of

January 2020, there were almost 12,000 reported cases in Mainland China[1].

Given the networked and global character of contemporary societies, the

novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, referred to as “coronavirus” in this article) spread globally within a short time period. “Earlier experience had

shown that one of the downsides of increasing globalization is how impossible

it is to stop a rapid international diffusion of new diseases. We live in

a highly connected world where almost everyone travels. The human networks for

potential diffusion are vast and open” (Harvey 2020). On 11 March 2020, the World Health

Organization declared the coronavirus to be a pandemic. On 29 March 2020, there

were 638,146 confirmed coronavirus cases in a total of 203 countries that had

resulted in 30,105 deaths[2].

As a reaction to the virus threats to humankind and human lives, many countries introduced wide-ranging public health-measures such as the shutdown of public life and social distancing measures. This paper is a contribution to the social theory analysis of coronavirus crisis’ implications for society. It asks: How have everyday life and everyday communication changed in the coronavirus crisis? How does capitalism shape everyday life and everyday communication during this crisis?

Section 2 focuses

on how social space and everyday communication have changed due to the

coronavirus crisis. Section 3 focuses on the communication of ideology in the

context of coronavirus by analysing the communication of coronavirus conspiracy

stories and false coronavirus news.

As long as there is no vaccination against the coronavirus disease, the virus poses

a danger to the lives of all humans and the societies they form because it is

highly contagious and has a relatively high death rate that is manifold times

higher than the one of seasonal flu.

In order to fight the pandemic, WHO (2020) recommends “that social

distancing and quarantine measures need to be implemented in a timely and

thorough manner. Some of the measures that countries may consider adopting are:

closures of schools and universities, implementation of remote working

policies, minimizing the use of public transport in peak hours and deferment of

nonessential travel”.

Boris Johnson’s Social Darwinism

As a reaction to the pandemic, social distancing was implemented as a

public health measure in many countries. Some have taken strict measures such

as curfews, whereas others only recommended social distancing but did not

enforce it by law. Some countries have shifted their policies. Boris Johnson’s

Conservative government in the UK first took a laissez-faire approach. It did

not shut down public life. It later took measures common in many countries

continental Europe such as the closure of schools and non-essential businesses,

the prohibition of public events, and the order that people have to stay at

home.

In a press conference on March 12, Johnson said that due to coronavirus

“many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time”. At the

same time, he did not take measures such as shutting down public life as other

countries had already done at the same point of time. The strategy that he

announced together with his scientific and medical advisors was based on not

containing the virus but letting it spread until “herd immunity” is reached.

Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty argued that the “our top planning assumption

is up to 80 percent of the population being infected”. Given the UK has 66

million inhabitants and the death rate of coronavirus is on average one

percentage, this implies letting more than 500,000 people die from coronavirus

in order to reach what in medical jargon is called herd immunity. In a Sky News

interview, Chief Scientific Advisor Patrick Vallace

defended this approach by saying that “of course we do face the prospect of, as

the Prime Minister said yesterday, an increasing number of people dying. […]

This is a nasty disease”[3].

Johnson and his chief medical and chief scientific advisor chose a

social Darwinist approach where the fittest survive and the government

tolerates that others die although public health measures could reduce the

amount and share of deaths. Charles Darwin’s half-cousin Francis Galton

(1822-1911) argued that society should be based on “the workings of Nature by

securing that humanity shall be represented by the fittest” (Galton 1909, 42).

Just like the Thatcherism that the Tories have advanced preaches and practices

survival of the fittest companies in the capitalist economy, Johnson and his

advisors planned to use the same principle as population policy. The

implication is that those who are old, weak, and ill are sacrificed. In a

radically neoliberal society such as the United Kingdom and the USA, the

Darwinist Alfred Russel Wallace concept of nature is applied to society: in the

coronavirus crisis, the “best organised, or the most healthy,

or the most active, or the best protected, or the most intelligent, will

inevitably, in the long run, gain an advantage over those which are inferior in

these qualities; that is, the fittest will survive” (Wallace 1889/2009, 123).

Humans are social and societal beings. They live in and through social

relations in society. Communication is the process of the production and

reproduction of sociality, social relations, social structures, social systems,

and society (Fuchs 2020a). In a social relation, at least two humans make sense

of each other’s actions. Each of them interprets what the other one is doing,

which leads at least to new thoughts and potentially results in changes of the

social system. The measure of social distancing practiced as a response to the

coronavirus crisis doesn’t mean the dissolution but the radical reorganisation

of social relations. Humans avoid face-to-face social relations and substitute

them by mediated social relations, in which communication is organised with the

help of the telephone, social media, messenger and video communication software

such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Zoom, Skype, Panopto,

Blackboard Collaborate, Jitsi, Discord, etc. Social

distancing isn’t an avoidance of communication, but the substitution of

face-to-face communication that bears the risk of contagion by mediated

communication. Mediation becomes a strategy of both avoidance and survival.

Social distancing is not a distancing from the social and other humans, but

communication and sociality at a distance.

In 2020, billions

of humans experienced and practiced a radical rupture and reorganisation of their

social life. In modern society, we organise our everyday life as social

practices that take place in distinct social systems, where we repeatedly in a

routinised manner spend certain time periods together with others in order to

achieve certain goals. Key social systems of our everyday life include the

home, the workplace, and educational organisations (nursery, school,

university). And there are public spaces accessible to everyone where we spend

leisure time, meet others, commute from one place to another one, or organise

other aspects of our everyday life. Such spaces include parks, playgrounds,

cafés, trains, buses, the underground, shops, etc.

The division of

labour and activities means that humans spend certain times of the day in

particular spaces. An example is work in an office or factory from Monday to

Friday between 9am and 5pm. This means that space and time are zoned into

particular time periods spent at certain places. The flexibilization,

globalisation, digitalisation, individualisation, and neoliberalization

of capitalist society have transformed the space-time of everyday life. More

and more people work from different spaces, including their home and public

spaces, at a variety of times. The workplace, the home, and public spaces have

partly converged. The boundaries between leisure time and labour time, play and

labour, consumption and production, the office and the home, etc. have become

blurred. For many people, this tendency has meant an increase of their

labour-time and the extension of the logic of capital into spheres outside of

the traditional workplace. More and more people have had to work more in order

to survive, but have only done so in precarious ways.

The coronavirus crisis brought about a radical transformation of the space-time

of everyday life. Workplaces and public spaces shut down. The physical and

social differentiation of the spaces of everyday life collapsed. Workplaces and

schools suddenly completely converged with the home as the space of everyday

life. The blurring and convergence of social spaces that had been advanced by

neoliberalism was suddenly taken to its extreme. The intermediary spaces of

public life, where we used to spend leisure time and transit times in cafés,

restaurants, parks, nature, public transport, etc. emptied out, which created

ghost towns and urban ghost spaces.

Politicians had to

decide between two basic policy options in light of the coronavirus crisis,

namely to either radically disrupt everyday life and ask the majority of

citizens to stay at home or to minimally disrupt everyday life. The first

option tries to save human lives by reducing the direct communication and

direct social relations as far as possible and thereby inevitably creates an

economic crisis. The second option keeps up direct communication and direct

social relations, which risks human lives in order to try to avoid an economic

crisis.

In existential

crises such as the coronavirus crisis, neoliberal political strategies choose

to keep most businesses open. In contrast, socialist government strategies shut

all non-essential businesses that are not needed to guarantee the survival of

society. In the second strategy, human life and well-being stand above economic

interests. In the first strategy, economic growth and profitability are put

before human life.

Social space is

structured and regionalised into specific locales. These are time-space

locations, zones, stations, and domains such as homes, streets, cities,

workplaces, schools, nurseries, parks, shops, restaurants, cafés, means of

public transport, etc. “Locales refer to the use of space to provide the settings of interaction, the

settings of interaction in turn being essential to specifying its contexuality. […] Locales

may range from a room in a house, a street corner, the shop floor of a factory,

towns and cities, to the territorially demarcated areas occupied by

nation-states. But locales are typically internally regionalized, and the regions within them are of

critical importance in constituting contexts of interaction” (Giddens 1984,

118).

A locale is a

particular physical or virtual space that is used at particular time, typically

in a routinised manner, which implies repetition, for social actions and

communication that have a particular goal. Space-time is organised in the form

of demarcated and bounded zones or regions (locales) that are the physical,

spatial and temporal context of specific types of action and communication.

Locales are the places and physical settings of humans’ communicative

practices.

In the coronavirus

crisis, the social spaces and locales of work, leisure, education, the public

sphere, the private sphere, friendships, family converge in the locale of the

home. The home is at the same time workplace, family and private space, school,

nursery, leisure space, natural space, a public space from where we connect to

friends and professional contacts, etc. Social spaces converge in the home. In

this convergent social space, it can easily become difficult to organise

everyday life by breaking up time into small portions of which each is

dedicated to specific activities in a routinised manner. In the coronavirus

crisis, the home has become the supra-locale of everyday life.

Whereas daytime

used to be for many individuals working time, at the time of the coronavirus

crisis it has to be simultaneously working time, play time, educational time,

family time, shopping time, housework time, leisure time, care time,

psychological coping time, etc. The convergence of social spaces in the home is

accompanied by the convergence of time periods dedicated to specific

activities. The result is that activities that humans usually perform in

different social roles at different times in different locales converge in

activities that are conducted in one universal, tendentially unzoned and unstructured space-time in one locale, the

home.

This convergence can easily result in an overburdening of the individual who

cannot manage multiple social roles at the same time in one locale. The

situation is made worse by the exceptional psychological burdens that the

coronavirus crisis causes, where individuals worry about the lives of their

family, friends and themselves, have to think of how to organise everyday

activities such as shopping and going out without risking their life and

others’ lives, have to cope with not being physically close to their family

members, parents and friends, dedicate time to supporting old, weak and ill

people from their families and communities who self-isolate, etc. In such a

crisis, lots of time is survival time, time used for activities that secure

immediate physical, psychological, and social survival. Routine activities

become challenging tasks to which significant amounts of time need to be

dedicated.

Survival work

shapes everyday life in the coronavirus crisis. Given that direct communication

is limited, more time needs to be spent on organising communication at a

distance. There are times where individuals are not able to properly continue

and “function” because they have to cope with fears of death, illness, and the

future. In times of crisis, humans like to come together with their closest

companions in order to help and support one another. In the coronavirus crisis,

physical proximity of larger groups is discouraged because it increases the

risks of contagion, illness, and death. Social distancing puts psychological

burdens on many humans because they cannot be physically close to some or many

of their loved ones. Mediated communication can provide some emotional support,

but lacks the capacity of touching, feeling, smelling, hugging, etc. one

another. You can say nice words to a friend or relative via a webcam, but you

cannot look him or her into the eyes, which is part of empathetic

communication. Physical proximity is an important aspect of care that is

missing in the coronavirus crisis, which puts additional psychological burdens

on individuals. It is much more difficult to communicate emotions, love,

solidarity, and empathy in mediated communication than in face-to-face

communication.

Houseworkers have

traditionally had to deal with multiple types of work, including care,

education, cleaning, cooking, shopping, etc., at the same time in the locale of

the home. In a sense, the coronavirus crisis is a process of radical mass housewifization that confines work, social action, and

communication to the locale of the home. This condition has been

characteristic for houseworkers since a long time (Mies,

Bennholdt-Thomsen and Werlhof

1988).

It is decisive how

the state acts in such a situation of profound emergency. There is a continuum

of state action ranging from neoliberal action to socialist action. Neoliberal

state action tolerates unemployment and precarity of workers and is only

concerned with bailing out companies. It does not secure the social security,

livelihood, income, rent payments, and survival of the working class. Socialist

state action in contrast secures the survival of the working class by measures

such as an unconditional basic income during crisis time, the continuation of

wage payments for workers and freelancers, rent freezing, etc.

Socialist crisis

action makes sure that humans have the time and resources needed to survive the

crisis without becoming poor, indebted, bankrupt, etc. It recognises the need

of humans for sufficient time during which they engage in survival work. It

provides the material foundations needed for survival work.

Neoliberal crisis

action tolerates an increase of poverty, misery, debt, precarity, homelessness,

unemployment etc. in order to reorganise society in the interest of capital in

a state of emergency. Thinking this logic to its end implies that neoliberal

crisis management establishes a state-organised dictatorship of capital that

enslaves the impoverished, indebted, and precarious working class that

struggles to survive. The coronavirus crisis is a rupture and existential

crisis of society that poses both potentials for the development of socialism

and solidarity on the one side and slavery and fascist dictatorship on the

other side.

Based on the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s (1974/1991) theory of

space, the critical theorist David Harvey (2005) provides a typology of social

space (see table 1). Using Lefebvre’s distinction between perceived, conceived,

and lived spaces as three dimensions of space, Harvey distinguishes between

physical space, representations of space, and spaces of representation. He adds

to Lefebvre’s theory the distinction between absolute, relative, and relational

space. Spaces are absolute in that they are locales that have certain physical

boundaries. They are relative because objects are placed in them that have

certain distances from each other. And they are relational because these

objects stand in relations to each other. In society, humans produce and reproduce

social space by a dialectic of social practices and social structures. The

cells in table 1 describe particular aspects of social space.

|

|

Physical space (experienced space) |

Representations of space (conceptualised space) |

Spaces of representation |

|

Absolute

space |

physical locale |

symbols, maps and plans

of physical locales |

locales as social spaces

where humans live, work, and communicate |

|

Relative

space (time) |

humans in a physical

locale |

symbols used and meanings

created by humans in physical locales |

humans as social actors

acting in social roles |

|

Relational

space (time) |

social relations of

humans in a physical locale |

language as social and

societal structure |

communicative practices

that produce and reproduce social relations, sociality, and social spaces |

Table 1: David Harvey’s (2005) typology of social space

Table 2 shows how social spaces are changing and organised in the coronavirus crisis.

|

|

Physical

space (experienced space) |

Representations

of space (conceptualised space) |

Spaces

of representation |

|

Absolute

space |

the home as the supra-locale |

plans and strategies of how to use the

supra-locale of the home for the organisation of everyday life |

the home as the dominant social spaces and

supra-social space where humans simultaneously organise multiple aspects of

their life and work, convergence of absolute spaces in the home |

|

Relative

space (time) |

humans stay predominantly in one locale,

their homes |

symbols used and meanings created by

humans in the supra-locale of the home |

convergence of humans’ social roles in the

supra-space of the home |

|

Relational

space (time) |

social relations at a physical distance

organised via communication technologies between home locales |

language as social structure |

the convergence of humans’ communicative

practices in the convergent space and under conditions of the convergent time

of the home, mediation of the convergence of space-time by communication

technologies |

In the coronavirus crisis, humans are largely confined to the physical

space of the home, for which certain organisational strategies are needed so

that everyday life can be organised from the home. Humans experience,

conceptualise, live and thereby also produce social space-time in manners that

make social spaces converge in the supra-time-space of the home. Communication

technologies play a decisive role in organising everyday life from the locale

of the home in the coronavirus crisis.

Everyday life refers to social practices within the totality of society

(Lefebvre 2002, 31). Everyday life is an “intermediate and mediating level” of society (45). Lefebvre

identifies three dimensions of everyday life: natural forms of necessity, the

economic realm of the appropriation of objects and goods, and the realm of

culture (62). So Lefebvre sees nature, the economy, and culture as the three

important realms of everyday life. What is missing is the realm of politics,

where humans take collective decisions that are binding for all and take on the

forms of rules. The critique of everyday life analyses how humans live, “how

badly they live, or how they do not live at all” (18). Lefebvre argues that in

phases of fundamental societal change, “everyday

life is suspended, shattered or changed” (109). The coronavirus crisis has

suspended, shattered, and necessitated the reorganisation of the practices,

structures, and routines of everyday life.

|

The

lived (le vécu) |

The

living (le vivre) |

|

individual |

group |

|

experience, knowledge, doing |

context, horizon |

|

practices |

structures |

|

present |

presenc |

Table 3: Lefebvre’s distinction between the lived and the living (source: Lefebvre 2002, 166, 216-218)

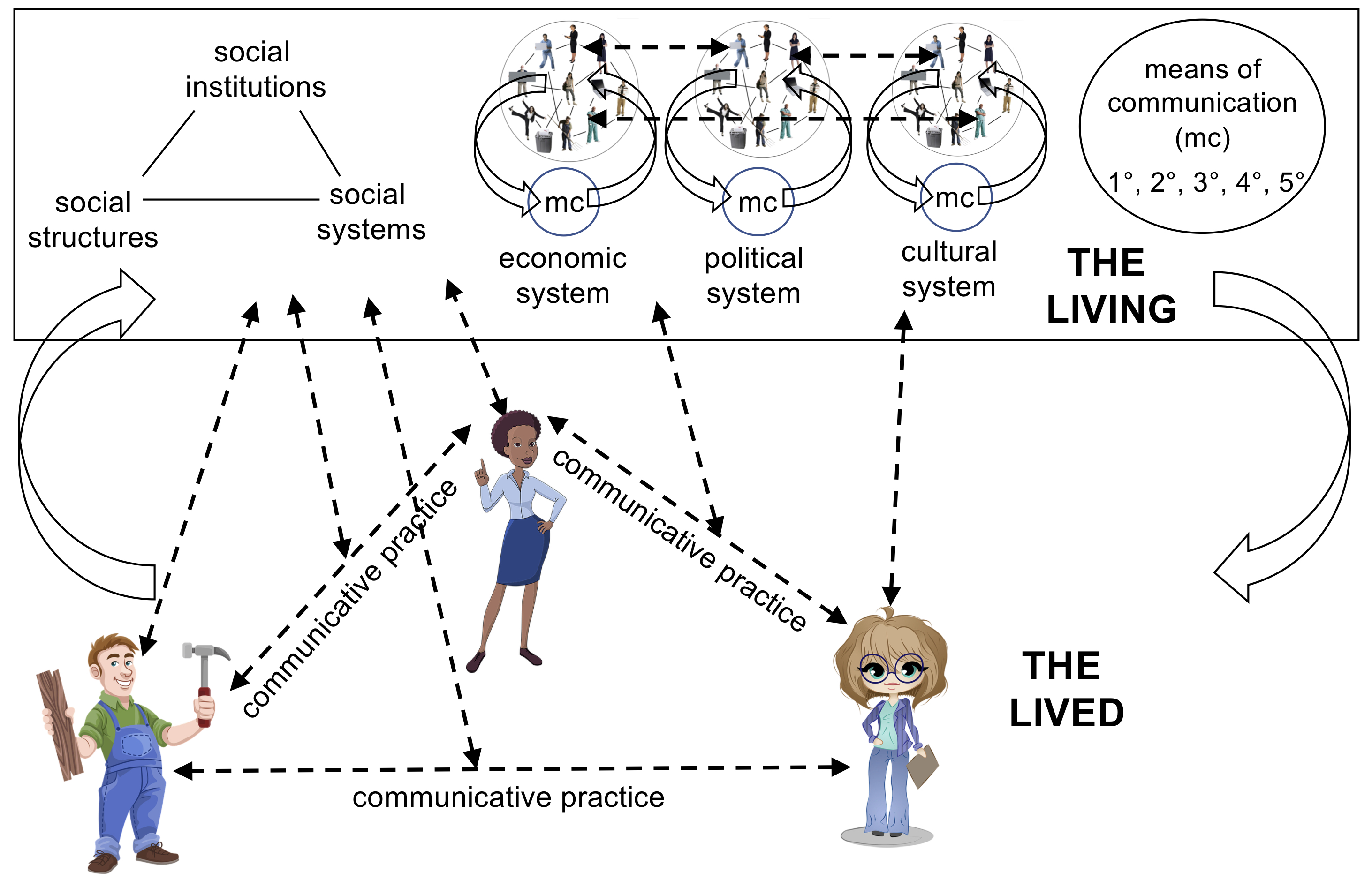

Lefebvre distinguishes between the lived (le vécu) and the living (le vivre) as two levels of everyday life (see table 3). Figure 1 shows a model of everyday life.

At the level of lived reality, humans produce social objects through communicative practices. They do so under the conditions of the living, i.e. structural conditions that enable and constrain human practices, production, and communication. The level of living life consists of an interaction of social structures, social systems, and social institutions. All structures, systems and institutions have economic, political, and cultural dimensions. In many social systems, one of these dimensions is dominant so that we can differentiate between economic, political and cultural structures/systems/institutions. At the level of lived life, humans relate to each other through communicative practices. These communicative practices are the foundations of the production, reproduction, and differentiation of economic, political, and cultural structures/systems/institutions that condition human practices. There is a dialectic of the living and the lived in any society. This is a dialectic of human subjects and social objects.

Figure 1: Everyday life and everyday communication

Means of communication mediate the dialectic of objects and subjects and the relations between humans. We can distinguish five types of the means of communication (table 4).

|

|

Role of mediation by technology |

Examples |

|

Primary communication technologies |

Human body and mind, no media technology is used for the production,

distribution, reception of information |

Theatre, concert, performance, interpersonal communication |

|

Secondary communication technologies |

Use of media technology for the production of information |

Newspapers, magazines, books, technologically produced arts and

culture |

|

Tertiary communication technologies |

Use of media technology for the production and consumption of

information, not for distribution |

CDs, DVDs, tapes, records, Blu-ray disks, hard disks |

|

Quaternary communication technologies |

Use of media technology for the production, distribution and

consumption of information |

TV, radio, film, telephone, Internet |

|

Quinary communication technologies |

Digital media prosumption technologies, user-generated content |

Internet, social media |

Table 4: Five types of the means of communication

Figure 2 visualises the transformation of everyday life and everyday

communication at the time of the coronavirus crisis. Humans isolate themselves

and therefore avoid direct communicative relations. This circumstance is

visualised at the level of the lived by enclosed individuals and small enclosed

groups. Dense networks of direct communication and direct social relations are

suspended. At the structural level of the lived, the economic, political and

cultural dimensions are not organised as separate locales but tend to converge

in the social system of the home that takes on the form of a supra-locale from

where economic, political and the cultural life are organised and structured

from a distance. Humans spend the vast majority of their time in physical isolation

in their homes, from where they access and organise social structures, systems,

and institutions at a distance by making use of secondary, tertiary,

quaternary, and quinary means of communication. The use of the primary means of

communication, namely face-to-face communication, is avoided. Whereas under

regular conditions humans organise the economy, politics, and culture in the

form of separate social systems that they access in everyday life by commuting

to different specialised physical locales, in the coronavirus crisis

specialised physical locales are suspended. These systems’ structural social

roles are preserved: a multitude of humans who are located in the physical

locales of their homes organises these systems at a distance with the help of mediated

communication. Humans hardly communicate with each other face-to-face but

through mediating communication technologies.

Figure 2: Everyday life and everyday communication in the coronavirus crisis

The Coronavirus Crisis as

Deceleration of Everyday Life?

In the coronavirus crisis, most people traverse only smaller physical

distances and fewer goods are transported so that everyday life is decelerated

and comes to a relative standstill. There are fewer people for overall less

time on the streets, in public and intermediate spaces. At the same time, the

number of social activities and communicative practices taking place from the

home and conducted from there at a distance massively increases. As a

consequence, communication networks such as the Internet and mobile phone

networks are used at a maximum capacity. The thinning out of social activity in

public spaces corresponds to the thickening and multiplication of social

activities taking place in the home and locally. The coronavirus crisis deglobalizes

and therefore localises everyday life.

The German sociologist Hartmut

Rosa (2020b) argues that the corona virus crisis means “forced deceleration”[4]. He argues that there is a “massive deceleration of real

physical life, where on the one hand one feels silenced and excluded but on the

other hand one discovers new forms of solidarity and new forms of amenability”[5] (Rosa 2020b). Rosa is

rather optimistic about the consequences of the coronavirus crisis. On the one

hand he sees the loss of ontological security and trust so that “relationships

become suspect”[6]

and there is “growing alienation”[7] (Rosa 2020a). On the other

hand, he sees new opportunities for resonance, a condition where humans enter

into unalienated relations with others and the world: “We have time. Suddenly

we can hear and experience what is happening around us: Maybe we indeed hear

the birds, look at the flowers and greet the neighbours. Hearing and answering

instead of domination and control are the beginning of a relation of resonance

from which something novel can emerge”[8] (Rosa 2020a).

Socialism or Barbarism

The coronavirus crisis certainly means that humans make fewer direct social

relations, commute much less, live quite locally, and traverse less physical

distance. But this does not necessarily imply the deceleration of social life.

The speed of social life has to do with the amount of experiences we make per

unit of time. Even if we do not move at all, we can live in a high-speed

society where vast amounts of information are rapidly processed and large

numbers of decisions are taken and many actions are performed per unit of time.

Whether or not the coronavirus crisis is an opportunity for generally slowing

down the pace of modern life is first and foremost a question of political

economy. It depends on whether or not governments take measures that allow

humans to survive without depending on constantly having to perform labour

under precarious conditions and provide material foundations that help to avoid

an overburdening of the individual from the convergence of social spaces,

social times, and social roles.

What humans realise in the coronavirus crisis is that life, wellbeing, health, and survival are not self-evident. This crisis is a radical confrontation of the individual and society by death. The collective experience of the fear of death can create new forms of solidarity in society and elements of socialism. The ”threat of viral infection also gave a tremendous boost to new forms of local and global solidarity, plus it made clear the need for control over power itself. […] the present crisis demonstrates clearly how global solidarity and cooperation is in the interest of the survival of all and each of us” (Žižek 2020). But if right-wing demagogues manage to ideologically manipulate these fears, then the realisation of such potentials might be destroyed and fascist potentials that divide society and advance dictatorship, genocide, war, inhumanity, and mass murder might be realised. The coronavirus crisis radicalises the perspectives for the future of society. It makes it more likely that we are either heading towards socialism or barbarism.

The Most Vulnerable

In the coronavirus crisis, those worst hit and most vulnerable are

humans who do not have a home to which they can retreat such as the homeless

and refugees who are on the run or live in refugee camps. It is very difficult

for these groups to shield themselves from the virus. In the coronavirus

crisis, politicians can either protect these vulnerable groups by creating and

providing suitable shelters that allow social distancing or abandon them by not

providing support, which implies that many vulnerable individuals will die. Humans

in developing countries face the problem that they often live in overcrowded

spaces in poor metropolises or in areas that lack access to water, soap,

hospitals, doctors, etc. Protective measures such as social distancing and

washing one’s hands can therefore be more difficult to organise in developing

countries. The lack of material foundations of protection therefore can

especially affect and harm humans in poor countries and regions.

The Working Class in the Coronavirus Crisis

Life and work have been radically transformed in the coronavirus crisis. There

is a group of workers who cannot work from home and from a distance. They

depend on a differentiation of social spaces and direct social relations in

order to produce. Examples include personal services (cooks, cleaners, waiters,

bartenders, hairdressers, travel attendants, childcare workers, etc.),

manufacturing labour, construction labour, agricultural work, food processing

labour, garment labour, drivers, transport labour, refuse labour, elementary

labour etc.

Many of these

occupations have low and medium skills and rather low wages. Given that many

workplaces were shut down in the coronavirus crisis, lower-paid and lower-skill

workers who depend on direct social relations and the access to work spaces

outside their homes faced a high likelihood of becoming unemployed. For

example, in Austria the number of the unemployed rose from around 400,000 to

550,000 within ten days in March 2020 (APA 2020). The largest share of the

newly unemployed belonged to the economic sectors of accommodation, gastronomy,

and construction (APA 2020).

In the coronavirus

crisis, especially highly qualified white-collar workers can continue to work

from their homes. This includes both employees and freelancers. Think for example

of the activities of architects, managers, scientists, engineers, designers,

teachers, academics, writers, artists, analysts, administrators, accountants

and financial workers, marketing and public relations workers, software

developers and other digital workers creating digital goods and services,

lawyers, translators, secretaries, typists, call centre agents, consultants,

etc. Such workers may in principle be able to work from home. In many

countries, there is a general guideline or rule in the coronavirus crisis that

says that those who can conduct their work from home should or have to do so.

There are two main

problems such workers face:

a) they may face

social and psychological overburdening when trying to work in the home that at

the time of an existential crisis is a convergent space of manifold activities,

including care work, educational work, wage-labour, survival work, etc.

b) given the

relative shutdown of society, there is a reduced demand for services, which

means that there might be diminishing sources of income for many homeworkers.

It is decisive how

governments support white-collar workers and other workers in the coronavirus

crisis. Neoliberal strategies put capital and economic growth first, which

means that white-collar workers are expected to work at normal capacity and

pace from home and cannot rely on special support. Socialist strategies put

survival, health, well-being, and social security first and therefore support

white-collar workers and other workers materially so that they do not face the

existential danger of material ruin.

There is a number of occupations in the organisation of critical

infrastructures that are necessary for society’s survival in an existential

crisis. Such foundational work is performed by, for example, doctors, nurses,

care workers, midwives, paramedics, pharmacists, psychologists, firefighters,

public transport workers, journalists, public service media workers, police

officers, food producers, food processing workers, food delivery and transport

workers, supermarket workers, post office and delivery workers, sanitation

workers, pharmaceutical workers, manufacturing and assemblage workers producing

medical equipment, utility workers, telecommunications workers, emergency

workers, legal sector workers, etc.

Workers in critical

infrastructural sectors face a higher risk of falling themselves ill because in

their work they have more direct social contacts than others. Think for example

of doctors and nurses treating COVID-19 patients in hospitals. It is important

that governments and organisations do everything that is possible in order to

provide protective equipment, measures, and working conditions that protect

these workers. A particular problem during the coronavirus crisis was the lack

of protective equipment, as a result of which many nurses and doctors contracted

the virus. Workers in critical infrastructures show a high level of solidarity that is needed for

securing the survival of society and humankind. It is insufficient that they

are publicly lauded as heroes. The crucial importance of their work should be

acknowledged not just symbolically but also economically and socially by e.g.

special bonus payments that are not just symbolic, special retirements

benefits, etc.

Especially in

emergency situations, the market provision of key infrastructures is

bound to

fail because the commodity form operates based on the profit principle

and not

on the principle of human interest. Insofar as key infrastructures are

not

public services, establishing public ownership combined with worker

control is

a measure that puts humanism over the logic of capital accumulation.

Neoliberalism has in countries such as the USA and the United Kingdom

prevented

or undermined the public provision of health care. As a consequence,

there is a

lack of resources in (including personnel and physical resources) and

of

individuals’ access to the health care system. In a state of exception

such as

the coronavirus crisis, dysfunctional health care systems multiply the

number

of deaths. It has become evident that universal health care and public

ownership of the care sector are of crucial importance for guaranteeing

wellbeing for everyone. The writer and activist Mike Davis (2020)

argues in this context that the coronavirus pandemic shows that

“capitalist globalization now appears to be biologically unsus-tainable

in the absence of a truly international public health infrastructure”.

Bernie Sanders commented in this context in the

following way on the coronavirus crisis:

“[M]illions

of people are now demanding that we have a government that works for all. What

role should the campaign play in continuing that fight to make sure that health

care becomes a human right, not a privilege, that we raise the minimum wage to

a living wage, et cetera, et cetera. people now understand that it is

incomprehensible that we remain the only major country on earth not to

guarantee health care to all, that we have an economy which leaves half of our

people [...] living paycheck to paycheck.

[…] What kind of system is it where people today are dying, knowing they're

sick, but they're not going to the hospital because they can't afford the bill

that they'll be picking up?” (Sprunt 2020).

The implication of Sander’s programme is that countries struck by

coronavirus should “hire enough

people to identify COVID-19 home-by-home right now and equip them with the

needed protective gear, such as adequate masks. Along the way, we need to

suspend a society organized around expropriation, from landlords up through

sanctions on other countries, so that people can survive both the disease and its

cure” (Wallace et al. 2020). Coronavirus makes evident that the world needs to

realise a global right to public healthcare, i.e. public healthcare at a high

standard for all. “The spiral form of endless capital accumulation is

collapsing inward from one part of the world to every other. The only thing

that can save it is a government funded and inspired mass consumerism conjured

out of nothing. This will require socializing the whole of the economy […] without

calling it socialism” (Harvey 2020).

Old people and people

suffering from cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes,

cancer or having a weakened immune system are at a particular risk to die from

coronavirus. Many governments therefore have recommended or mandated that

at-risk groups should stay at home and isolate themselves. This, however,

entails the problem that reduced direct social contacts might be experienced as

a psychological burden. The use of communication technologies for staying in

touch with loved ones and communities is not a fix for the lack of direct

social contacts, although it is a means for providing certain forms of

emotional support. Older people, however, face a digital divide. This group’s

physical, motivational and skills access to digital technologies such as

computers, the Internet, laptops, tablets, mobile phones, apps, social media,

etc. is significantly lower than in the younger generation. In 2019, 98 percent

of EU citizens aged 16-24 were Internet users, whereas only 60 percent of those

aged 65-75 uses the Internet. In the age group of 65-75, 31 percent had low and

2 percent no digital skills 2019[9].

Given the digital divide, older people face a

particular risk of feeling lonely and depressed as a result of social

distancing. Whereas neoliberal strategies simply tell pensioners to isolate

without supporting measures, a socialist strategy devises measures in order to

alleviate the psychological burdens of social isolation. Examples include social

and community services that provide food, install easy-to-use communication

technologies in at-risk group members’ homes, engage in daily contacts with

at-risk individuals, etc.

In the coronavirus crisis, many countries shut nurseries, primary and secondary

schools, as well as universities. As a consequences, children and youth needed

to stay at home with their parents. The general expectation has been that

teaching continues at a distance making use of e-mail, video conferencing,

messaging systems, and a variety of e-learning technologies.

The first problem

that arises is that children, and especially small children, need lots of

attention, which conflicts with parents being able to work from home. Parents

have to act not just as workers and carers, but also as teachers. A socialist

strategy has to put childcare and well-being over labour. The implication is

that in an existential crisis of society, wages should be continued to be paid

and subsidised by governments without performance expectations. States of

emergency are radical ruptures of society and everyday day. One cannot expect

that life, work, and education can continue as normal. Therefore, also the

educational performance expectations of pupils and students should be suspended

or put at a minimum level. One feasible option is that learning materials and

support are provided but there are no exams and all students and pupils

automatically pass.

The second problem

is that e-learning that is purely mediated and virtual tends to be inefficient

and difficult to organise. Therefore, blended learning where virtual learning

at a distance is combined with face-to-face learning sessions has become the

generally accepted standard in e-learning. Blended learning “is the full

integration of face-to-face and online activities. […] Blended learning can

include the blending of individual and collaborative activities, modes of

communication (verbal and written), and a range of face-to-face and online

courses that constitute a blended program of studies“ (Garrison 2011, 75-76).

Blended learning “represents a significant conceptual and practical

breakthrough in enhancing the quality of teaching and learning […] The great

advantage of blended learning is that while it is transformative, it builds

upon traditional ideals of communities of learners and familiar face-to-face

learning” (Garrison 2011, 82).

The radical virtuality of e-learning in the coronavirus crisis easily

reaches limits and causes problems. Keeping up the performance principles of

grading, success, and failure under such difficult learning conditions is

counterproductive to the cultural and social development of young people.

Global capitalism created a power gap between global cities on the one side and

rural areas on the other side. Global

cities are urban spatial agglomerations of capital, labour-power,

companies, banks, infrastructure, corporate headquarters, service industries, international

financial services, telecommunication facilities, etc. Global cities include,

for example, New York, London, Tokyo, Paris, Frankfurt, Zurich, Amsterdam, Los

Angeles, Sydney, São Paulo, Mexico City, and Hong Kong. “The more globally the

economy becomes, the higher the agglomeration of central functions in a

relatively few sites, that is, the global cities“ (Sassen

1991, 5). “The need to minimize circulation costs as well as turnover times

promotes agglomeration of production

within a few large urban centers which become,

in effect, the workshops of capitalist production” (Harvey 2001, 245).

Geographical expansion goes hand in hand with geographical concentration (Harvey 2001, 246).

Whereas wealth and

power are concentrated in global cities, there is a lack of resources, people,

and infrastructures in many rural areas, which is a source of social problems.

In the coronavirus crisis, people living in densely populated global cities are

at a disadvantage in comparison to those in rural areas. There is a lack of

natural spaces and accessible gardens in global cities, which makes it hard for

families and individuals living in such cities to endure quarantine and social

isolation. It is especially difficult for those who have kids but live in small

apartments without access to a garden. In addition, the high population density

in global cities makes it more likely and easier that the virus spreads than in

sparsely populated rural areas. People in rural areas are less likely to

contract the coronavirus and they have better access to nature, which makes it

easier to cope with quarantine measures.

“High-density human populations would seem an easy host

target. It is well known that measles epidemics, for example, only flourish in

larger urban population centers but rapidly die out

in sparsely populated regions. How human beings interact with each other, move

around, discipline themselves, or forget to wash their hands affects how

diseases get transmitted” (Harvey 2020).

In the coronavirus crisis, the unequal geography has partly been

reversed in respect to the absolute and relative number of illnesses and death.

Rural areas certainly can face the disadvantage of less equipped and advanced

hospitals, but their inhabitants are less likely to contract coronavirus than

the inhabitants of global cities.

Section 2 focused

on the analysis of a variety of aspects of everyday life and everyday

communication in the coronavirus crisis. It outlined profound changes of how

space-time is organised in societies struck by the pandemic. It became evident

that the well-being of everyday people depends on political economy and what

policies governments takes in response to the crisis. Political responses to

the crisis range on a continuum between neoliberalism on the one side and

socialism on the other side. The next section will focus on how and what type

of ideology is communicated in the context of the coronavirus crisis.

3.

The Communication of Coronavirus Conspiracy Stories and False News

Slavoj Žižek (2020) warns against not taking the coronavirus serious:

“Both alt-right and fake Left refuse to

accept the full reality of the epidemic, each watering it down in an exercise

of social-constructivist reduction […] Trump and his partisans repeatedly

insist that the epidemic is a plot by Democrats and China to make him lose the

upcoming elections, while some on the Left denounce the measures proposed by

the state and health apparatuses as tainted by xenophobia and, therefore,

insist on shaking hands, etc. Such a stance misses the paradox: not to shake

hands and to go into isolation when needed IS today’s form of solidarity”.

Downplaying and denying the seriousness of coronavirus is an ideological

dimension of the crisis. The spreading of fake news is another manifestation of

ideology in the state of exception.

There is no generally accepted

definition of fake news. The core of many definitions is that fake news is

factually false news that is circulated online, predominantly on social media,

lacks journalistic professional norms, and tries to systematically and

deliberately mislead and misinform (Fuchs 2021, chapter 7). Some observers

prefer to use the terms mis- or disinformation. Some of those who spread fake

news, such as Donald Trump, use the term in order to try to attack credible

news sources. Based on the tradition of ideology critique that stresses that

false consciousness is an expression of ideological attempts to manipulate the

public’s perception of reality, a critical theory approach to fake news should

better use the term “false news”. False news is an expression of a highly

polarised political landscape, where lies are used for trying to manipulate

election results and decision-making (Fuchs 2020b).

The Cambridge Analytica scandal was a

typical manifestation of false news (ibid.). In false news culture, facts are declared to be wrong and lies

are declared to be true. There is a distrust of experts, liberals, and

socialists. There is a distrust towards facts and rationality and a belief that

truth is what one finds ideologically and emotionally agreeable. Demagogues try

to scapegoat experts and political opponents by claiming that they form an

elite that hates the people and considers them as silly. Demagogues spreading

false information claim that they stand on the side of the people who share

their ideology and that elites deliberately bias and misrepresent reality.

The

coronavirus crisis created a state of exception in many countries and parts of

the world. Suddenly billions of people’s everyday life was disrupted and had to

be reorganised. They have had to fear for their lives and the lives of friends

and family. They have had to think of how to organise their children’s care,

how to manage to live in isolation, how to best organise shopping, how to deal

with the situation’s psychological stress, etc. The situation of crisis,

uncertain futures, collective shock, and the collective fear of death

characteristic for the coronavirus emergency is a futile ground for the spread

of false news. We do not know exactly what the motivations of those spreading

false coronavirus news have been, but it is possible to provide an overview of

the main themes of false stories that have circulated at the time of the global

spread of the pandemic[10].

Types of False Coronavirus News

There are two main types of false coronavirus news stories:

a) false

news related to the origin of coronavirus;

b) false

news about how the virus is contracted and can be killed.

The first

type focuses on how coronavirus is produced, the second on how it circulates

and can be destroyed.

Fake news stories about the origin of coronavirus:

·

The coronavirus is a Chinese biological weapon

developed in the Wuhan Institute of Technology.

·

The Chinese government collaborated with other

forces, such as the Democratic Party in the USA or the North Korean government,

in releasing the virus in order to bring down Donald Trump.

·

The CIA created and spread the virus as a

biological weapon in order to challenge the economic and political power of

China, Russia, or Iran.

·

Israel developed and spread the virus in order

to create a financial market crisis and financially benefit from the resulting

volatility.

·

Israel or Jews such as the Rothschild family

manufactured the virus in order to seize world power.

·

Chinese spies stole the virus from a virus

research laboratory in Canada.

·

COVID-19 is part of a population control

strategy developed by Bill Gates and the UK-government funded Pirbright

Institute.

·

Donald Trump created the pandemic in order to

arrest or kill paedophiles, political opponents, and Hollywood actors.

·

Eating meat is the cause of coronavirus.

Fake news stories about contracting and killing

coronavirus:

·

A vaccine against infection already exists.

·

Cocaine cures coronavirus.

·

Africans are resistant.

·

5G wireless networks caused the outbreak of

coronavirus.

·

Pets spread coronavirus.

·

Vinegar kills coronavirus.

·

Drinking boiled ginger or lemon water or cow

urine kills coronavirus.

·

Gargling bleach kills coronavirus.

·

Going to the sauna kills coronavirus.

·

Using a hair dryer kills coronavirus.

·

Taking medicinal herbs kills coronavirus.

·

The Holy Communion protects one from

coronavirus.

·

Using silver-infused toothpaste kills

coronavirus.

·

Spiritual healing kills coronavirus.

Breitbart, Rush Limbaugh, and False Coronavirus News

Let us have a look at an example of a false

coronavirus news story. Breitbart is a far-right propaganda website. On 27

March 2020, it was the 256th most accessed web platform in the world[11].

This means that Breitbart stories reach a very large audience. On 24 February

2020, Breitbart ran a story about right-wing radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh.

The Rush Limbaugh Show is with

an average of more than 15 million listeners not just the USA’s

most-listened-to talk radio show, but also the country’s most-listened-to radio

programme[12].

Created in 1988, this show is a prototype and main manifestation of far-right

broadcasting. It airs on weekdays and around 600 local radio stations broadcast

it.

The Breitbart article’s title was “Limbaugh:

Coronavirus Being ‘Weaponized’ to Bring Down Trump”[13].

Limbaugh claimed that “probably

is a ChiCom [Chinese communist] laboratory experiment

that is in the process of being weaponized. All superpower nations weaponize

bioweapons. […] It looks like the coronavirus is being weaponized as yet

another element to bring down Donald Trump. I want to tell you the truth about

the coronavirus”[14]. “Some

people believe that it got out on purpose, that the ChiComs

have a whole lot of problems based on an economy that cannot provide for the

number of people they have. So losing a few people here and there [is] not so

bad for the Chinese government”[15].

“The coronavirus is an effort to get Trump”[16].

So what Limbaugh claims is that China manufactured the

coronavirus in order to target the USA with a bioweapon and weaken Trump’s

political position by bringing about many deaths. Fact-checking organisation PolitiFact analysed the claims

made in this episode of The Limbaugh Show and concluded that the claims were

false[17].

Breitbart also

made use of its social media channels in order to spread Rush Limbaugh’s

conspiracy theory. At the time of writing, Breitbart had more than 4 million

followers on Facebook, 1.2 million followers on Twitter, 620k followers on

Instagram, and 160k subscribers on YouTube[18]. On 25 February 2020, Breitbart posted

a link to the Limbaugh-story on its Facebook page (see figure 3). On 28 March,

the Facebook posting had been shard 900 times, and had received 4,200 emotional

reactions and 1,200 comments. At the same point of time, 2,279 users had

commented on the news article on the Breitbart platform to which the Facebook

posting linked.

Figure 3: Breitbart’s spreading of Rush Limbaugh’s coronavirus

conspiracy on social media, https://www.facebook.com/Breitbart/posts/rush-limbaugh-it-looks-like-the-coronavirus-is-being-weaponized-as-yet-another-e/10164646988865354/,

accessed on 28 March 2020

The example of Rush Limbaugh’s conspiracy

claim that China manufactured coronavirus in order to bring down Donald Trump

shows how the far-right uses a combination of different media in order to

spread false news in the public. In this particular case, the broadcast medium

of radio was used in order to launch a false news story. Breitbart used the

Internet and social media in order to amplify the false news story. Broadcast

media and social media that allow commenting and sharing together amplified the

audience reach and thereby the spread of coronavirus false news.

Like all conspiracy stories, Limbaugh’s claims lack evidence and ignore

the findings of experts. He builds on the ideological conviction and moral

outrage of Trump-supporters who think that there is a big conspiracy where

intellectuals, socialists, liberals, and foreign countries try to attack the

United States.

False news ignores

scientific evidence. There are no indications that the coronavirus was

manufactured by humans. The DNA sequences of the coronavirus are

most closely related to viruses found in bats (Cohen 2020a, York 2020, Ye 2020,

Zhou 2020). Based on environmental sampling, there is evidence that the virus

was contracted from animals to humans at Wuhan seafood market (ibid.).

Scientists found out that animals such as the pangolin could be the species

mediating the infection between bats and humans (Cyranoski

2020, Lam et al. 2020). Andersen et al. (2020) write based on an analysis of

the virus-genome that they “do not believe that any type of laboratory-based

scenario is plausible”.

Ignoring scientific

evidence, a variety of conspiracy theories has emerged around COVID-19. “Speculations

have included the possibility that the virus was bioengineered in the lab [Wuhan

Institute of Virology] or that a lab worker was infected while handling a bat

and then transmitted the disease to others outside the lab” (Cohen 2020b). In a

letter to leading medical journal The

Lancet, 27 public health scientists “strongly condemn conspiracy theories

suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin. […] Conspiracy

theories do nothing but create fear, rumours, and prejudice that jeopardise our

global collaboration in the fight against this virus” (Calisher et al. 2020,

e42). Scientists “overwhelmingly conclude that this coronavirus originated in

wildlife” (Calisher et al. 2020, e42).

The coronavirus pandemic is a crisis of humankind. The virus was

transferred from animals to humans and given the global and mobile character of

societies, it spread globally within three months causing many deaths. Given

that contemporary societies are not nationally contained, but involve the

international transport of goods and people and global travelling, a novel

virus can originate in and spread globally from any part of the Earth. What the

far-right tries to do is to deflect attention from the fact that the coronavirus

crisis is a crisis of humanity that can only be overcome by global solidarity

among and mutual aid of humans.

The far-right ideologizes the virus. They declare coronavirus to be a

project designed and manufactured by single nations in order to weaken, attack,

and try to destroy other nations. Their goal is to use the crisis situation in

order to radicalise nationalism and spread nationalist hatred among the

populations of different countries. It is not a rational assumption that a

country such as China spreads a virus in its own country, which causes many

deaths, in order to attack other countries. Coronavirus has caused many deaths

in all parts of the world. Coronavirus ideology works by combining nationalism

and conspiracy thinking. The far-right uses traditional mass media and social

media in order to spread nationalism and hatred in the context of a crisis of

humanity.

Donald Trump repeatedly spoke of coronavirus as the “Chinese virus”

(Mangan 2020). The World Health Organization warned against this term, saying

that viruses “know no borders and they don’t care about your ethnicity, the color of your skin or how much money you have in the bank.

So it’s really important we be careful in the language we use lest it lead to the profiling of individuals associated with the

virus” (Kopecki 2020). The danger of nationalist

ideology in a state of exception and a crisis of humanity is that authoritarian

characters such as Trump are prone to use violence, which can result in wars,

nuclear attacks, the creation of a fascist state, etc.

There is a social dimension of the coronavirus crisis: there is a large

number of persons who fall seriously ill or die. The relative standstill of

society necessary for containing the virus translates into economic crisis. And

there is a political dimension of the coronavirus crisis, where nationalism and

ideology can bring about the rise of fascism and world war. Coronavirus is a

natural disaster that threatens humanity. Irrational reactions such as

nationalism, ideology, and violence pose a serious danger in such profound

crises. The lack of solidarity and the displacement of solidarity by

nationalism can turn a natural disaster that brings about a social and economic

crisis into a political crisis that features war, mass killings, genocide, and

fascism.

4. Conclusion

This paper asked: How have everyday life and everyday communication

changed in the coronavirus crisis? How does capitalism shape everyday life and

everyday communication during this crisis?

We can summarise the main findings:

·

Social distancing:

The social distancing practiced during the coronavirus crisis isn’t an

avoidance of communication and social relations, but the substitution of

face-to-face communication that bears the risk of contagion by mediated

communication. Social distancing is not the distanciation from sociality and

communication but rather sociality and communication at a distance.

·

The rupture of everyday life and everyday

communication:

The coronavirus crisis brought

about a radical transformation of the space-time of everyday life and everyday

communication. In this crisis, the social spaces and locales of work, leisure,

education, the public sphere, the private sphere, friendships, family converge

in the locale of the home. The home takes on the role of the supra-locale of everyday

life from which humans organise society at a distance with the help of

communication technologies. Activities that humans usually perform in different

social roles at different times in different locales converge in activities

conducted in one universal, tendentially unzoned and

unstructured space-time in one locale, the home.

·

The danger of overburdening individuals:

The convergence of space-time in the home characteristic for the

coronavirus crisis can easily overburden the individual who cannot manage

multiple social roles at the same time in one locale. Public health policies

that unburden the individual are therefore of key importance for managing such

a crisis.

·

Communication technologies as means of

sociality at a distance:

Communication technologies play an important role in the organisation of

everyday social life under the exceptional conditions that the coronavirus

crisis poses for society and individuals. Primary means of communication are by

and large avoided. There is the wide use of mediated communication with the

help of secondary, tertiary, quaternary and quinary means of communication.

Face-to-face communication is replaced by mediated communication, which creates

challenges because closeness, love, and emotions are hard to achieve and

communicate in mediated communication. You cannot hug someone over the

Internet.

·

Coronavirus and class structures:

Although everyone can contract coronavirus, the social effects of the

pandemic are unequally distributed along class structures. The poor, the old,

the weak, and the ill are especially vulnerable and affected. Whereas some

workers can continue to work from home but face the danger of overburdening

activities and lack of demand, other workers lose their jobs and face the

danger of destitution, unemployment, and homelessness.

·

Government measures:

Government responses to the coronavirus crisis range on a continuum

between neoliberalism and socialism. Neoliberal strategies could for example be

found in the United Kingdom. They take a laissez-faire approach that avoids

disrupting everyday life and put economic growth and the profit imperative over

human interests and human lives. Everyone is left to themselves, which means

that only the strong survive. Such responses make clear that neoliberalism is a

form of social Darwinism. Socialist strategies are based on the idea of

collective solidarity in fighting the pandemic. Measures are taken that

minimise the death toll and try to safeguard a good life for everyone. Human

interests and human lives are put over capitalist

interests. The coronavirus crisis is an existential crisis of humanity and

society. Socialist measures aim at providing resources and forms of relief to

humans that allow them enough time for survival labour in order to better cope

with the difficulties of the ruptures of everyday life and to be better able to

reorganise routine activities, cope with fears and anxiety, support friends,

family, and communities, etc.

·

False

coronavirus news:

The

collective shock and the collective fear of death that emerged in the

coronavirus crisis are a futile ground for the spread of false news about

coronavirus.

·

Types of

false coronavirus news:

There are two

main types of false coronavirus news stories:

a) false news related to the origin of coronavirus;

b) false news about how the virus is contracted and can be killed.

·

The far-right’s communication of false

coronavirus news:

The far-right has taken advantage of the

coronavirus crisis in order to spread nationalism and hatred by communicating

false coronavirus news stories via traditional and social media.

Socialism or Barbarism

The coronavirus crisis is an existential crisis of humanity and society. It

radically confronts humans with death and the fear of death. This collective

experience can on the one hand result in new forms of solidarity and socialism.

Humans realise that life, wellbeing, health and survival are their most

important and most fundamental goods, that they need to take care of themselves

and of each other, and that collective and global solidarity is needed in order

to overcome the pandemic.

But

on the other hand there is the danger of war and fascism. The biggest political

danger of the coronavirus crisis is that the far-right uses the state of

emergency in order to spread false news, nationalism, hatred, which can result

in violence, warfare, dictatorship, genocide, and fascism. The coronavirus

crisis radicalises the perspectives for the future of society. It makes it more

likely that we are either heading towards socialism or barbarism. Just like

hundred years ago, bourgeois society also today and in the coming time “stands at the crossroads, either transition

to socialism or regression into barbarism” (Luxemburg 1916, 388). “In this

hour, socialism is the only salvation for humanity” (Luxemburg 1971, 367).

Andersen, Kristian G. 2020. The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9

APA (Austria Press Agency). 2020. 153.100 mehr Arbeitslose seit 15. März. Wiener Zeitung, 25 March 2020, https://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/wirtschaft/oesterreich/2055625-153.100-mehr-Arbeitslose-seit-15.-Maerz.html

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Calisher, Charles et al. 2020. Statement in Support of the Scientists, Public Health Professionals, and Medical Professionals of China Combatting COVID-19. The Lancet 395: e42-e43, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30418-9

Cohen, John. 2020a. Mining Coronavirus Genomes for Clues to the Outbreak’s Origins. Science Magazine, 31 January 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/01/mining-coronavirus-genomes-clues-outbreak-s-origins#

Cohen, John. 2020b. Scientists “Strongly Condemn” Rumors and Conspiracy Theories About Origin of Coronavirus Outbreak. Science Magazine, 19 February 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/scientists-strongly-condemn-rumors-and-conspiracy-theories-about-origin-coronavirus#

Cyranoski, David. 2020. Mystery Deepens Over Animal Source of Coronavirus. Nature 579: 18-19.

Davis, Mike. 2020. In a Plague Year. Jacobin, 14 March 2020, https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/mike-davis-coronavirus-outbreak-capitalism-left-international-solidarity

Fuchs, Christian. 2021. Social Media: A Critical Introduction. London: Sage. Third edition.

Fuchs, Christian. 2020a. Communication and Capitalism. A Critical Theory. London: University of Westminster Press.

Fuchs, Christian. 2020b. Nationalism on the Internet: Critical Theory and Ideology in the Age of Social Media and Fake News. New York: Routledge.

Galton, Francis. 1909. Essays in in Eugenics. London: The Eugenics Education Society.

Garrison, Randy D. 2011. E-Learning in the 21st Century. A Framework for Research and Practice. New York: Routledge. Second edition.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity.

Harvey, David. 2020. Anti-Capitalist Politics in the Time of COVID-19. Jacobin, 20 March 2020, https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/david-harvey-coronavirus-political-economy-disruptions

Harvey, David. 2005. Space as Keyword. In Spaces of Neoliberalization, 93-115. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Harvey, David. 2001. Spaces of Capital. Towards a Critical Geography. New York: Routledge.

Kopecki, Dawn. 2020. WHO Officials Warn US President Trump Against Calling Cornavirus the “Chinese Virus”. CNBC, 18 March 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/18/who-officials-warn-us-president-trump-against-calling-coronavirus-the-chinese-virus.html

Lam, Tommy Tsan-Yuk et al. 2020. Identifying SARS-CoV-2 Related Coronaviruses in Malayan Pangolins. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0

Lefebvre, Henri. 2002. Critique of Everyday Life. Volume II: Foundations for a Sociology of the Everyday. London: Verso.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1974/1991. The Production of Space. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Li, Xiang et al. 2020. Bat Origin of a New Human Coronavirus: There and Back Again. Science China Life Sciences 63: 461-462, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-020-1645-7

Luxemburg, Rosa. 1971. Selected

Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

Luxemburg, Rosa.

1916. The Junius Pamphlet. In Rosa Luxemburg

Speaks, 371-477. New York: Pathfinder.

Mangan, Dan. 2020. Trump Blames China for Coronavirus Pandemic: “The Worls is Paying A Very Big Price for What They Did”. CNBC, 19 March 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/19/coronavirus-outbreak-trump-blames-china-for-virus-again.html

Mies, Maria, Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen, and Claudia von Werlhof. 1988. Women: The Last Colony. London: Zed Books.

Rosa, Hartmut. 2020a. Interview. Philosophie Magazin, 18 March 2020, https://philomag.de/auf-einmal-sind-wir-nicht-mehr-die-gejagten/

Rosa, Hartmut. 2020b. Interview. TAZ, 25 March 2020, https://taz.de/Soziologe-Hartmut-Rosa-ueber-Corona/!5673868/

Sassen, Saskia. 1991. The Global City. Princeton, NJL Princeton University Press.

Sprunt, Barbara. 2020. Bernie Sanders on His Campaign: “It’s Going to Be A Very Steep Road”. NPR, 27 March 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/03/27/822171139/bernie-sanders-on-his-campaign-it-s-going-to-be-a-very-steep-road?t=1585500234287

Wallace, Alfred Russel. 1889/2009. Darwinism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wallace, Rob, Alex Liebman, Luis Fernando Chavez and Rodrick Wallace. 2020. COVID-19 and Circuits of Capital. Monthly Review 72, https://monthlyreview.org/2020/03/27/covid-19-and-circuits-of-capital/

World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. WHO Announces COVID-19 Outbreak a Pandemic. WHO, 12 March 2020, http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic

Ye, Zi-Wei et al. 2020. Zoontic Origins of Human Coronavirus. International Journal of Biological Sciences 16 (10): 1686-1697.

York, Ashley. 2020. Novel Coronavirus Takes Flight From Bats? Nature Reviews Microbiology 18: 191.

Zhou, Peng et al. 2020. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated With a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 579: 270-273.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2020. Monitor and Punish? Yes, Please! The Philosophical Salon, 16 March 2020, http://thephilosophicalsalon.com/monitor-and-punish-yes-please/

Christian Fuchs

Christian Fuchs is co-editor of the journal tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, a critical theorist of society and communication, and author of many books and articles. @fuchschristian; http://fuchsc.net, http://www.triple-c.at

[1] Data source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019%E2%80%9320_coronavirus_pandemic_in_mainland_China

[2] Data source: WHO, https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019, accessed on 30 March 2020.

[4] Translation from German: „Zwangsentschleunigung”.

[5] Translation from German: „Dem

steht eine massive Verlangsamung im realen physischen Leben gegenüber. Wo man