Created in 2010, Instagram is nowadays one of the most-used social media platforms, with more than 1 billion users worldwide (Instagram 2019). Designed for mobile use, the app consists of sharing, liking and commenting on images and videos commonly subtitled by hashtags that algorithmically group users’ posts. Even though Instagram currently hosts advertising in an explicit and conventional fashion whereby companies pay for native advertisement, this was not the case until 2014 (Carah and Shaul 2016), before which it was ad-free. Facing commercial barriers, advertising companies were required to find new ways of penetrating the social tissue of the platform, either by creating individual accounts or through the instrumentalisation of certain users to promote their content. Reinforcing the latter, Instagram has become in recent years a strategic social media platform for influencer-marketing, whereby companies target popular Instagram users for the promotion of their brands at the exchange of income or visibility (Duffy 2017, 139). These users, so-called “influencers”, can be defined as “one form of microcelebrity who accumulate a following on blogs and social media through textual and visual narrations of their personal everyday lives, upon which advertorials[1] for products and services are premised” (Abidin 2016b, 86). Common means of brand promotion include tagging or hashtagging a brand in user-generated content whilst displaying a particular product. These branding practices, at first sight limited to a group of influencers, have proliferated in the platform to such an extent that common, unpaid users (who are not regarded as a valuable asset to influencer marketing) now undertake the same practices.

Under this scenario, this article asks: in what ways are influencers inciting widespread branding practices on the Instagram platform? How do these practices affect the identity of Instagram users? By placing the emphasis on common users, this article urges an analysis of the reification of branding practices on social media, since these practices reverse what can be considered a top-down fashion of targeting consumers: common users themselves target brands and search for that interaction.

Considering the identity-intensive milieu of the Instagram platform, the first section of this article draws on a possible formulation of identity in order to explore how the edification of user profiles entails a formulation of the individual within regimes of subjectification that require the incorporation of certain rationales. In order to propose an understanding of how the use of Instagram might be inciting a generalisation of branding practices amongst common users, I will use Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of habitus, since it pertains to the formation of dispositions in individuals towards certain practices. In this regard, and playing a crucial role in my argument, I will deploy the role of influencers in inducing certain forms of engagement with the social media platform by exploring literature related to the concept of cultural intermediaries, rooted in the universe of consumer culture.

Considering debates on digital labour (Fuchs 2014; Lazzarato 1996; Terranova 2012) and evidenced by the value-generation avenues resulting from the practice of brand-tagging and hashtagging undertaken by common users, in the third section of this article I will examine current practices in light of theories on digital labour. In this sense, labour will play a double role in my argument since it allows for exploring the form of labour taking place not only structurally but, most importantly, subjectively, as far as “labouring practices produce collective subjectivities, produce sociality, and ultimately produce society itself” (Hardt 1999, 89). By comparing branding practices undertaken by potential influencers with those carried out by common users, this article explores the extent to which the Instagram platform perpetuates not only a generalised labourhood but also the prosumption of particular identity formulations. In the final section of the article, I will reflect on the potential effects of this labour on the identity of individuals.

2. Regimes of Subjectification: Outlining the Identities of the Digital

The purpose of this discussion urges for a definition of identity which, although not consensual or stable, allows reflection on how Instagram might be inducing a certain form of individual identity. For that, we should first recognise that social media structures and activities are not a totalising part of individual life. In the same way, this article calls for a fragmented conceptualisation of identity, in the sense that it considers individual identity as an assemblage of temporally and spatially situated moments. I would like to bear on Nikolas Rose’s work on the genealogy of self, and particularly on his concept of “regimes of subjectification” (1996, 18) as a means of proposing a reflection of what may be at stake in the establishment of an identity on social media. Inspired by Foucault, Rose explores the contemporary self by looking at “the complex of apparatuses, practices, machinations, and assemblages within which human being has been fabricated” (1996, 10), or what is then termed “regimes of subjectification”. In Rose’s view, these regimes are embedded in the modes of subjectification of the self because they act upon the “ways in which humans ‘give meaning to experience’” (1996, 25), creating certain ways of being human. For instance, an ethical regime, a regime of the body or of freedom, are all imbricated in the regimes of subjectification, revealing how questions of power and knowledge intrinsically modulate the practices of the self: “they form the horizon of what is thinkable” (1996, 18).

Reflecting on Instagram in light of Rose’s regimes of subjectification enables one to perceive the role of the platform in being part of and producing a heterogeneity of regimes of subjectification where a certain normativity is played. In fact, the extent of literature produced that establishes a relation between individuals and social media has employed concepts such as self-tracking, self-optimisation (Lupton 2014; 2015) and self-curation (Abidin 2016a), underlining the engagement of social media users in a process of reconstitution of the self through social media platforms. The instant possibility of revising oneself through a device results in a process of transformation towards an ideal image of oneself that replaces the supposed instantaneity of posted content by a curated digital persona (Abidin 2016a). These ideal images of oneself are themselves part of a regime of subjectification which cannot be detached from other assemblages of power. As the universe of users’ branding practices under scrutiny in this article underlines, self-branding – “a conscious impression management strategy that deploys ‘cultural meanings and images drawn from the narratives and visual codes of the mainstream cultural industries’” (Duffy 2017, 69) – further emphasises the impregnation of certain regimes in the identity-edification of Instagram users. As Khamis et al. (2017, 10) point out, self-branding “represents a seminal turning point in how subjectivity itself is understood and articulated”, especially given the apparent control of individuals over their social media identities.

With the aim of understanding how branding practices on Instagram have surged among common users, we will now turn our analysis to the key role played by influencers. Feeding on conceptualisations of cultural intermediaries, the following section will further define the role of influencers in relation to greater structures of economic reasoning, taking into account questions of labour and subjectivity in the field of social media usage.

3. Instagram as a Form of Labour

Whilst aware of its fragilities[2], exploring the concept of “cultural intermediaries” sheds some light on the role that influencers might play in creating dispositions towards certain forms of engagement with social media. Through this concept – which was generically put forward by Pierre Bourdieu in his major oeuvre (Distinction, 2010) – Maguire (2014) considers the emergence of cultural intermediaries as being related to an economic system that not only requires the production of needs but also intends to create an ideal self, based on consumerist behaviours. The professionalisation of cultural intermediaries as taste-makers reproduces “both the consumer economy and the class positions of their practitioners” (Maguire 2014, 19). In fact, cultural intermediaries vitally require mechanisms of visibility to reinforce their legitimacy, mechanisms on which Instagram influencers are also quantitatively dependent (followers/following ratio) given the unidirectionality of the practice (i.e. one can follow a user but not be followed by that same user). Emerging along with a growth on investment in influencer marketing, the professionalisation of influencers as (often precariously (Duffy 2017)) remunerated professionals intensifies the display of branding practices on social media. Simultaneously, there is an expansion of PR and image-management businesses aiming at “packing” social media influencers in line with “social-scoring measurement mechanisms” like Klout, as extensively analysed by Hearn and Schoenhoff (2015).

The penetration of branding practices on Instagram, embodied by influencers, may be the source of their expansion among common users (CU) by fostering certain dispositions. Pierre Bourdieu’s work (2010) allows reflection on how influencers might be inducing a form of exploited labour in the platform given that branding practices have been taken up by CU. Through his formulation of the “habitus” as “not only a structuring structure, which organises practices and perception of practices, but also a structured structure” (Bourdieu 2010, 166), one can acknowledge that Instagram’s highly visual field potentiates a process of internalisation and externalisation of practices. Through the adoption of these practices, individuals strive to modulate their trajectory by accumulating certain forms of capital and, as Hearn and Schoenhoff (2015, 204) note, “move from being fans to being producers of free promotional content for brands”.

Situating this analysis within the frames of labour, rather than the frames of work, is revealing of the precariousness of using commercial social media platforms, from which Instagram is no exception:

Labour is a necessarily alienated form of work, in which humans do not control and own the means and results of production. It is a historic form of the organisation of work in class societies. Work in contrast is a much more general concept common to all societies. It is a process, in which humans make use of technologies for transforming nature and society in such a way that goods and services are created that satisfy human needs. (Fuchs 2014, 27)

Fuchs (2014, 95) puts forward three elements of exploitation present in digital labour:

1. the appropriation and commodification of users’ data;

2. users’ alienation from the means of production;

3. the maintenance of social relations.

To begin with, perhaps the most famous argument surrounding public debates are questions related to the (1) appropriation and commodification of users’ data, which is then sold to commercial companies for a number of purposes, including targeted advertisement: “exploitation is already on-going by the circumstance that users create a data commodity, in which their online work time is objectified [...] Corporate Internet platforms offer the data commodity that is the result of Internet prosumption” (Fuchs 2014, 96). The pervasiveness of this practice touches not only questions of privacy and surveillance, but also the notion of individuals’ own financial value, as groups of data are not uniformly priced: the value of data is defined by parameters such as the characteristics of a group and the number of biddings made by interested buyers. As such, users themselves are producing surplus-value for giant commercial companies that, by paradoxically providing ‘free of charge’ use of social media platforms like Instagram, generate huge financial profits.

Not owning the means of production (in this case, the social media platform), users are (2) alienated from the profit resulting from their own productivities. On Instagram, this alienation is furthered by the absence of users’ legal ownership over their posted content (Hearn and Schoenhoff 2015; Bosher and Yeşiloğlu 2019), and also fed by the platform’s regime of the free, which camouflages the commodification of their leisure time. Despite manifestos such as Wages for Facebook[3] and a greater awareness of the labour practice involved in the use of commercial social media, opting to abandon these platforms should not be defined as a simple decision based on free choice. As argued by Fuchs (2014, 95), the third element of exploitation is precisely (3) ideological coercion based on the “creation and maintenance of social relationships, without which [...] [the users’] lives would be less meaningful”.

In essence, as argued by Fuchs (2014; 2015) the usage of commercial social media platforms supposes a form of exploited labour. However, if the latter is underlined by an imposed visual engagement with brands’ advertisements from which users can only escape by abandoning social media platforms, Instagram seems to undertake a radically different logic for which the degree of imposition might be difficult to ascertain: we are assisting to a deliberate and explicit engagement with advertising brands and practices. Here, users are not so much targeted by advertising; rather, users attach their personal content production to brands through tagging and hashtagging practices, thus radically inverting what can be considered the expected top-down relation between users and brands in commercial social media platforms so far.

The following sections explore user-generated content (UGC) collected on Instagram through operating a ‘#’ plus ‘name of a brand’ search on Instagram’s search bar, to analyse branding practices undertaken on Instagram. Two groups of users – potential influencers (PI) and common users (CU) – were set out with the purpose of comparing UGC and inherent branding practices among the two categories of users. The latter have been defined by taking into account the user’s following/followers ratio as well as the location of content after performing the ‘#plusnameofthebrand’ search (content was either displayed under the “Top Posts” or the “Most Recent” sections).

4. Insta-factory: a Generalised Labourhood

The Instagram platform is an incessant flow of branded content production: for instance, in a two-hour period, 42 news images were posted under #prozis (a sports nutrition brand). There is a “continuous production of value that is completely immanent to the focus of the network society at large” (Terranova 2012, 34). On Instagram, we are in the realm of what Negri (1989) conceptualised as the “social factory”, accounting for a generalisation of labour – thus, of value production – through the tissue of life itself. The pertinence of the social factory comes from the socialised dimension of work, as far as production is dependent on cooperation and communication: here, subjects participate in the opening of “new flow-channels for value” (Negri 1989, 79). This concept allows for a reflection of the role of social media platforms in stimulating through social interactions a certain model of production from which user-generated content (UGC) acquires similar contours, as can be observed in Figure 1. The similarities in UGC can be attained as a factorisation of socialising practices of Instagram users, given not only the dense universe of tags/hashtags populating the platform, but also its embedded mechanisms, as will be explored in the following.

Figure 1: #missguided search on Instagram’s “Explore” tab

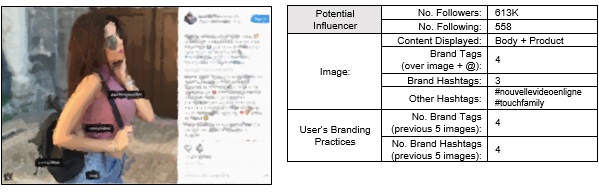

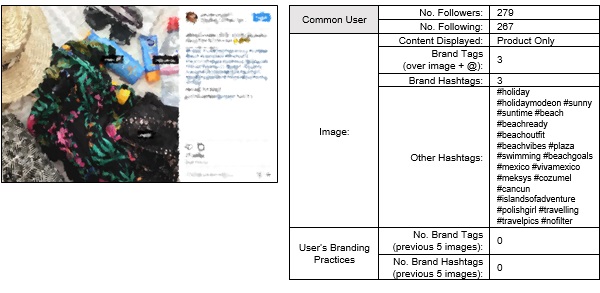

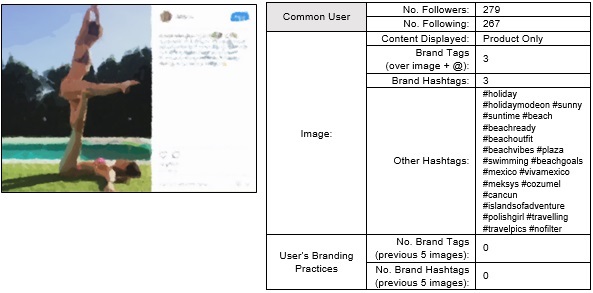

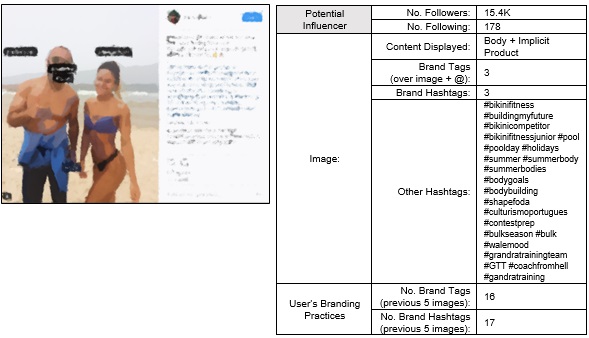

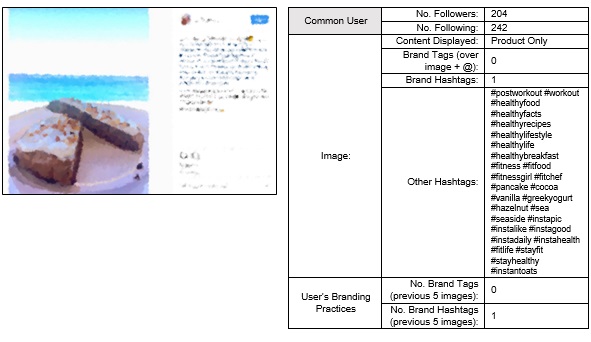

While both hashtags and tags can be used for the purpose of branding content, the manipulation of these practices varies significantly between CU and PI. Amid PI, the tag tends to be the favoured mechanism for branding content, revealing greater refinement and subtlety in the practice since the use of tags in UGC (contrary to hashtags) is not immediately perceived. Instead, its revelation requires clicking over the image and tend to be located on top of the objects they relate to, as Figure 2 shows. By contrast, the use of brand hashtags is significantly more popular among CU (see Figure 3), whose use of hashtags almost doubled that of PI. CU tend to make greater use of hashtags not only for naming brands but also to associate posted content to other non-branded references: in fact, most of the hashtags are representative of the image content (e.g. #miniskirt, #beer, #acroyoga) and situational, placing the content production within a chrono-topological frame (e.g. #instadaily, #miniholiday, #lunchtime). As we will see in the following section, CU deploy hashtags more intensively than PI not just to strive for visibility but mainly because these go beyond UGC.

Figure 2: PI displaying brand tags on top of products

Figure 3: CU tend to make greater use of hashtags than PI

Underlining this intensive use of hashtags, however, is the mechanism of wording suggestion and wording completion embedded in the Instagram platform, at work when a user types “#” on Instagram’s search bar. As a crucial dimension of Instagram’s value-creation apparatus, this mechanism (among others) underlines the crucial operation of targeting users with advertising or, most commonly, with advertorials, via the algorithmically generated “Explore” tab and the platform’s native advertisement. While Srnicek (2017, 45) rightly argues that data collection is part of a platform’s “DNA, as a model that enables other services and goods and technologies to be built on top of it”, it is important to stress that the self-branded user is becoming a vital part of the Instagram platform for the same purpose. With the unfolding of individuals on Instagram increasingly making use of mechanisms for branding content, CU participate in the development of businesses that go beyond the platform itself. At the same time, they enhance the value of Instagram as the influencer-marketing platform par excellence: it is no coincidence that nowadays “more than 90% of all influencer campaigns include Instagram as part of the marketing mix” (Influencer Marketing Hub 2020).

Whilst the platform works as a scattering of branding practices, users play a crucial role in the opening of Negri’s new flow-channels for value that sustain an ideological and symbolic commodity densification. Based on Fuchs’ approach to advertisement, transportation and a culturally established circulation play a crucial role in intensifying the symbolic value of a commodity, which eventually leads to different forms of surplus, such as a “fictitious form of use-value” (Fuchs 2015, 161). Thus, transportation and circulation, by acting upon the symbolic value of a commodity, further unbalance the relation between its use value and its exchange value. Nevertheless, if we were only facing continuous transportation – continuous flow – the intensification of the exchange-value of a commodity would never happen. This doesn’t mean that the generation of surplus-value is uniquely dependent on consumption practices proper; rather, and above all, it is dependent on the consumption and internalisation of an ideological commodity-dimension which confers that spurious value.

To this end, the user, within social media environment, should not be attained uniquely as a consumer, a structural purchaser, but, instead, as a prosumer (producer + consumer) of ideologies: a consumer because the user is approached in those flow-channels and inherently a producer due to the incorporation, alteration and participation in the dispersion of those flow-channels, of those ideologies. In the next section we will look more closely at the subjective labour imprinted by an ideological dimension occurring on the platform.

4.1. Identity Prosumption

With the online being “increasingly governed and delimited by private interests who own and control the platforms and affordances in and through which we express ourselves” (Hearn and Schoenhoff 2015, 203), the rise in self-branding practices concurs with the expansion of social media influencers. Alongside these, there is a dense universe of tagging and hashtagging practices targeting everyday, affordable and often supermarket-branded products that, being easily obtained and at low cost, expand the fraught assumption that, through self-branding practices, everyone can access the micro-celebrity status (Hearn and Schoenhoff 2015, 208).

In a fashion similar to advertising, PI tend to portray themselves together with branded products which, when not immediately apprehended, are implicitly exposed as embodied in their own selves. The latter can be observed particularly in content promoting fitness supplements, with the body being assumed as a result of certain product consumption. This embodiment of consumption practices matches a striving for authenticity and realness which, as Duffy (2017, 99) points out, is “increasingly compliant with the demands of capitalism”. Despite the less intensive use of hashtags in PI content, a clear narrative, intrinsically related to consumption choices, is being emphasised through the blend of content posted on their profiles.

The fact that CU make more use of hashtags than PI may be assigned not only to a striving for visibility but also for the reason that it becomes a structural element of performativity precisely because hashtags go beyond UGC. As conceptualisations of lived experiences, hashtags such as #fblogger, #hatobsessed, #gay, #polishgirl and #healthylifestyle are called into the process of self-curatorship to participate in the identity-edification of individuals on Instagram, elaborating over the visual elements of the images posted. It should be noted that, when hashtagging content, users are given suggestions of the most popular hashtags on the platform and also those they have previously used: if, on one hand, this hashtag production is modulated by the overall universe of practices, on the other hand, users are induced to be trapped in the perpetuation of the same meaning-creation of their previous experiences. These hashtags, seemingly delegated to a descriptive function, are revealing of the rationales penetrating UGC in the context of the Instagram platform. The employment of hashtags like #stayfit, #stayhealthy or #musthave, denotes a generalised set of lifestyles that feed into consumerist behaviours and on the enactment of oneself. Branding practices become part of a “set of practices which an individual embraces, not only because such practices fulfil utilitarian needs, but because they give material form to a particular narrative of self-identity” – what Giddens (1991, 81) defines as “lifestyles”.

Figure 4: Sportive lifestyle builds content even when not in a sportive venture

Nevertheless, the act of embracing something denotes a reflectiveness that, in the case of Instagram, deserves to be reconsidered, since there seems to exist a set of standardised lifestyle narratives, a pre-established range of forms available to define oneself. As matter of fact, the data collected shows that there is a prevalence of particular elements in UGC. For instance, by looking at Figure 5, we can see that the sportive lifestyle builds the generated content even when the user is not within a sportive venture; the same is observed in cases where the element of style and fashion branding is recurrent in apparent innate photography. Even so, the importance of consumption in building up an Instagram lifestyle seems to reach its apogee among CU who, more often than PI, generate content that displays the product only. Comparing Figures 6 and 7, it can be assumed that displaying the product only reflects an abandonment of the body potentially associated with the fact that users distrust their physical appearance as representative of what it should be like when associated with certain lifestyles – in this case, users who consume #prozis display the food they consume but do not trust their physicality as representative of their consumption practices, as a muscled or sportive body. Here, we see that, even if deploying less polished techniques of self-curatorship, CU also “internalise directives to brand the self” (Duffy 2017, 187 [emphasis in original]) and are equipped with a degree of tagging/hashtagging literacy that can only be reached by observing and mimicking others’ virtual behaviour.

Figure 5: PI displays the body as result of the consumption of #prozis products

Figure 6: CU who consume #prozis display the food they consume but do not trust their physicality as representative of their consumption practices.

There is a tendency for users to display content socially understood as valuable, or a positively valorised practice, (e.g. practicing yoga, spending time with friends, caring for the way they look). An identity is performed through the incorporation of a lifestyle based on consumerist behaviours of things accounted as good, beautiful, healthy and trendy, amongst others. The space of coexistence of PI and CU, realised through Instagram’s “Explore” tab, potentially enlarges the universe of branding practices, normalising the attachment of a brand to one’s image and creating dispositions towards that same practice. At the root of this phenomenon is the networked and algorithmically built mechanism of Instagram that enables influencers to reach out to users who are not necessarily part of their network of followers. As pointed out by Srnicek (2017, 26), platforms, “while often presenting themselves as empty spaces for others to interact on, [...] embody a politics”, a set of predefined rules, including the interface of the platform itself, to which users must comply and which serve the interests of platforms’ owners.

The growing number of PI undertaking branding practices through the platform’s incisive mechanism stimulates CU to become prosumers of their identities. To be precise, CU are, at first instance, consumers of visualised practices; thus of standardised lifestyles – as goods and as values – to subsequently become producers of their Instagram selves, reproducing established lifestyle narratives. They undertake an immaterial labour fostered by the nature of social media networks as ongoing flow-channels for value – a nature that, as mentioned above, is reinforced by users themselves. Coined by Lazzarato (1996), the concept of “immaterial labour” comes to designate the role of communication networks to the value generation of capitalistic societies: “the particularity of the commodity produced through immaterial labour [...] consists in the fact that it is not destroyed in the act of consumption, but rather it enlarges, transforms, and creates the ‘ideological’ and cultural environment of the consumer” (1996, 137).

4.2. A Universe of Laboured Identity

As demonstrated in the previous sections, incorporating a lifestyle arises as a process of self-curatorship towards what is valuable – the visibility of consumerist practices embodies values, expresses values and corroborates realms of social judgement penetrated by a capitalistic rationality. As work and leisure time tend to blend, as well as the private and public spheres, the elements of exploitation of laboured social media identities surpass an economic dimension to become, in addition, profoundly subjective. Contrary to the materiality of workplaces, Instagram is generally considered a free-time practice where users engage with others by sharing their life experiences. Yet its mechanisms act upon individual productivities to a similar extent as the workplace’s regimes of subjectification: the framing of actions, the maximisation of productivity, the hierarchisation of users and inherent competition and, most importantly, the standardisation of identity.

The reach of a neoliberal rational in all human endeavours underlines the relevance that branding practices attain. In a strive for self-valorisation, Instagram users construct an identity “designed for public consumption rather than personal reflection” (Khamis et al. 2017, 6). Yet, as Lazzarato (2009, 120) notes, “neoliberalism is a mode of government which consumes freedom, and to do so, it must first produce it and organise it”. As such, Instagram produces and organises a degree of freedom for user-generated content. This comes, in a first stage, from the platform’s embedded mechanisms (e.g. hashtags, “Explore” tab) and, secondly, from UGC itself. To be precise, the nature of UGC, concealed by the capital-accumulation regimes apprehended in the platform, becomes itself (re)productive of specific regimes of subjectification. In fact, UGC becomes ingrained in Instagram’s production and organisation of freedom because it works as “an administration of conducts” (Lazzarato 2009, 116) towards fellow users. In this particular realm of freedom, UGC is therefore consumed not only by the lifestyle narratives ‘available’ to its articulation, but also by the typification of identities apprehended through the platform.

For this reason, the reification of branding practices on Instagram should not be conceived as a simple incorporation of determined forms of engagement in social media platforms; rather, it entails a definition of oneself within regimes of subjectification which shape not only material practices but the subjectivity of individuals themselves. Here are convoked regimes of self-presentation that shape “what components of thought it connects up, what linkages it disavows, what it enables humans to imagine, to diagram, to hallucinate into existence, to assemble together” (Rose 1996, 178). Focusing not only on the language (as image and as text) used in the platform, but also on the regimes producing such language, we see that the ideologies sustaining a capitalistic society have permeated the layers of meaning that we associate with ourselves. Thus, more than stimulating consumption, the proliferation of branding practices on Instagram structures the way we make sense of our mundanity. As Srnicek (2017, 47) analyses in relation to the rhizomatic expansion of platforms as “owners of the infrastructures of society”, so the ideological dimension conveyed in these practices becomes an infrastructure of society: it calls for the elaboration of an identity limited to a set of capitalistically convenient practices where the emphasis on the surface of lifestyles jeopardises a potentially deeper sense of self.

5. Conclusion

This article proposed to explore in

what ways

influencers are encouraging widespread branding practices on Instagram

and how

these practices might affect the identity of its users. Evidenced by

the

analysis of both UGC and Instagram’s embedded mechanisms, it can be

claimed

that the engagement of common users with Instagram influencers

potentiates the

spread of branding practices on the platform. Not only do common users

undertake the practice of hashtagging/tagging brands, they also

demonstrate the

appropriation of regimented lifestyles. Thus, on the platform, users

get

acquainted with the ideologies to be deployed when labouring their

social media

identity, allowing for an ongoing appropriation and reproduction of

this labour

on Instagram.

The spread of branding practices on Instagram arouses a form of labour that

is not only structural, but also subjective, since an identity is

elaborated through

the consumption of lifestyles that entail a particular ideological

dimension.

This can be seen not only in branding practices proper but also in the

manipulation of non-branded hashtagging practices, showcasing that

users take

hold of an ideological meaning creation to make sense of their lived

experience. Instagram must hence be attained as a deeply political

universe

engrained by neoliberal rationales that, while giving a semblance of

autonomy,

limit the degree of freedom in which identity is elaborated, and

consequently, constrain

the subjectification of its users.

By displacing the object of analysis from influencers to common users, this article has raised awareness of the profound implications that the proliferation of branding practices has over common Instagram users. To overcome the limited scope of this contribution, further research could benefit from undertaking a social network analysis as a means of additionally exploring how Instagram interactions are shaping users’ performances in the platform, together with longitudinal research of individual profiles.

References

Foucault, Michel. 1986. The History of Sexuality (Vol.1). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Fuchs, Christian. 2015. Culture and Economy in the Age of Social Media. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Digital Labour and Karl Marx. New York: Routledge.

Goffman, Erving. 1990. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin.

Hardt, Michael. 1999. Affective Labour. boundary 26 (2): 89-100.

Influencer Marketing Hub. 2020. The State of Influencer Marketing 2020: Benchmark Report. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report-2020/

Instagram. 2019. Instagram Statistics. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://instagram-press.com/our-story/

Khamis, Susie, Ang Lawrence and Raymond Welling. 2017. Self-branding, ‘Micro-celebrity’ and the Rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebrity Studies 8 (2): 191-208, DOI: 10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

Lupton, Deborah. 2015. Digital Sociology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Marcuse, Herbert. 1964. One-Dimensional Man. Boston: Beacon.

Srnicek, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wages for Facebook. n.d. Accessed July 13, 2017. http://wagesforfacebook.com/

Williams, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

About the Author

Susana Aires

Susana Aires’ research interests focus on the impact of social media usage on individuals. Grounded by the current article, her research has evolved into exploring how the structural changes of social network sites affect the individuation process of its users, drawing on the work of Gilbert Simondon.