Abstract: Communism arrived in the south Indian state of Kerala in the early

twentieth century at a time when the matrilineal systems that governed

caste-Hindu relations were crumbling quickly. For a large part of the

twentieth century, the Communist Party – specifically the Communist

Party of India (Marxist) – played a major role in navigating Kerala

society through a developmental path based on equality, justice and

solidarity. Following Lefebvre’s conceptualisation of (social) space,

this paper explores how informal social spaces played an important

role in communicating ideas of communism and socialism to the masses.

Early communists used rural libraries and reading rooms, tea-shops,

public grounds and wall-art to engage with and communicate communism

to the masses. What can the efforts of the early communists in Kerala

tell us about the potential for communicative socialism? How can we

adapt these experiences in the twenty-first century? Using

autobiographies, memoirs, and personal interviews, this paper

addresses these questions.

Keywords: social spaces, communism, Kerala, modernity, autogestion, Henri Lefebvre

1.

Introduction

Kerala – a state that lies on the south-western end of the Indian peninsula – has remained a distinct part of India owing to its unique physical, cultural, and political characteristics. The Arabian Sea on its west and the Western Ghats (mountains) on its east have led to the evolution of a kind of insularity which has given it immunity from the political convulsions of Indian history which shook northern India (A. Menon 2015, 14; Damodaran and Vishvanathan 1995, 1). Until about two centuries ago, Kerala was among the most traditional regions of the country, with deep caste cleavages and rigid laws of purity and pollution that divided the populations. But over the twentieth-century, Kerala went on from being tagged as a “mad-house” of caste, to one of the most politically charged, secular and developed states in the country[1]. Although religion continued to influence basic attributes of Malayali identity, direct forms of oppression were less prevalent in Kerala’s public sphere than any other states by the 1970s (Nossiter 1982, 33).

Kerala also remains one of the few parts of India where the left-parties play an active and important socio-political role. Electorally, an alliance of left parties called the Left Democratic Front was formed post-independence, of which the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (hereafter CPI(M)) continues to be the largest political party. More importantly, the left has played a pivotal role in shaping public discourse and consciousness in Kerala since the 1930s, building on the religious and political reform movements initiated in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-centuries. Yet, this control of the communists over the public sphere has come under severe strain over the last few decades as forces of capitalism and religion threaten the secular social fabric of the society. At this critical juncture in history, this paper looks back at the twentieth-century and tease out the importance of social spaces in communicating communism to the masses in Kerala. The next section lays out the theoretical framework used for this paper. Section 3 describes briefly the context in which communism arrived in Kerala, before exploring the important role played by informal everyday social spaces. Although many such spaces emerged in post-independence Kerala, this paper focusses on two specific ones that have etched their place in popular imagination but have received little academic attention: reading-rooms and tea-shops. The last section discusses the changing nature of social spaces in the 21st century and communist responses.

The data presented here is a collection of content analysis of autobiographies and semi-structured personal interviews conducted over two periods of field visits in 2017 and 2018. A total of fourteen interviews were conducted and respondents were chosen using snowball sampling. Although no specific measures were taken to choose specific genders, religions or caste for the non-expert interviews, the fact that only two of the respondents were female reflects the fact that the public sphere in Kerala continues to be dominated by males. Autobiographies of E.M.S Namboodirippad and K. Madhavan, and a biography of Krishna Pillai – all communist leaders from Kerala – have been used.

2.

Social

Spaces

and the Public Sphere

Space – as an analytical tool – re-entered social theory in the last decades of twentieth-century after being treated as dead, fixed and immobile for generations (Foucault 1980, 70). Over the last three to four decades, many geographers, sociologists, and political scientists like David Harvey, Derek Gregory, Doreen Massey, Edward Soja, Laura Barraclough, Philip Howell, Christian Fuchs, Neil Brenner, and others have revisited the importance of space in shaping discourse, public opinions, and social relations. Henri Lefebvre’s (1991) seminal work The Production of Space continues to be a point of departure directly or indirectly for a number of these studies. In his work, Lefebvre points out that “space” remains a concept never fully conceptualised in social sciences. It continues to be used in myriad ways without being critically engaged with, and we are confronted with a “multitude of spaces, each one piled upon, or perhaps contained within the next: geographical, economic, demographic, sociological, ecological, political, commercial, national, continental, and global. Not to mention nature's (physical) space, the space of (energy) flows, and so on” (Lefebvre 1991, 2; 8).

Yet, Lefebvre asks, why is it that there is no spatial criticism on par with the criticism of art, literature, or music? This question leads Lefebvre in his endeavour to theorise space, and to conceptualise a unitary theory that separates physical (nature), mental (including logical and formal abstractions) and the social space, to discern their mutual relationships and differences, and to open up space to critical enquiry. Such a critical enquiry was contingent on a Marxist analysis of society:

the social relations of production have a social existence only insofar as they exist spatially; they project themselves into a space, they inscribe themselves in a space while producing it. Otherwise, they remain ‘pure’ abstraction, that is, in representations and consequently in ideology, or, stated differently, in verbalism, verbiage, words (Lefebvre, translated and cited in Soja 1989, 127-128).

The idea is not to arrive at a universal theory but a unitary one – to force social sciences to think about space seriously – and think critically about the importance of spatiality in better understanding social relations (Lefebvre 1991, 89).

We can begin to do this by separating space into three interconnected realms – representations of space (conceived space), spatial practice (perceived space), and representational space (lived space). Even as dominant power structures in society (colonial powers, higher castes, the State, capital) attempt to control representations of space and spatial practices, an absolute control remains unachievable, because the representational space remains subversive; “representational space is alive: it speaks” (Lefebvre 1991, 42). In other words, the lived spaces where human experience is shaped through the everyday social interactions also shape these interactions themselves. Especially in the modern state mode of production, a system where the State (and capital) increasingly control all spaces, Lefebvre argues that left forces must give up their utopianism and embrace the emancipatory potential of social spaces that arise from the constant contradictions between representations of space and representational spaces.

This paper

borrows from Lefebvre’s theory on the production of (social) spaces to

focus on the everyday spaces as being important in communicating an

ideology at a given time and space. Doing so would, on the one hand,

bring space into analysis, while on the other it also allows for human

experience as being considered central to understanding society,

especially in extremely diverse and hierarchical societies like India (Guru

and Sarukkai 2012; Guru and

Sarukkai 2019; Mohan 2016).

Fuchs (2019) has made a similar argument recently, pointing out that Lefebvre's humanist Marxism and the emphasis on human experience and social spaces can contribute to the foundations of a theory of communication. Here, I look at the case of the south Indian state of Kerala, where the political left has dominated the mainstream public sphere since the 1930s onwards[2]. For a revolution to be successful, it must create a new (social) space. When an ideology – any ideology – influences social relations in a society, it does so by producing new spaces or appropriating existing spaces. What then can be said of the spatiality of socialism? As Lefebvre asks, “has state socialism produced a space of its own?” (Lefebvre 1991, 54). What role did (social) spaces play in communicating socialism in twentieth-century Kerala? How have these spaces transformed in the twenty-first century, and how must the left-parties respond? These are the questions I address in this paper.

3.

Communism

and

(Social) Spaces in Kerala

Communism arrived in Kerala[3] in the early-twentieth-century, at a time when traditional social structures were being rapidly overthrown and a more progressive, modern, secular public sphere emerged. Pre-modern Kerala was organised in a Hindu Brahminical system[4] and the Namboodiris (Kerala Brahmins) controlled the ideological sphere as the repository of knowledge and discourse. Politically, land was divided into semi-autonomous temple-centred villages. Means of production were controlled by the large temple corporations managed by Namboodiris or the socially next-lower Nair castes. All villagers across castes were thereby directly or indirectly dependent on the temple for employment. There was, in other words, a spatiality to how the society, resources and communities were arranged. The idea of “body as space” is vital here because we see that the purity of the Namboodiri body was the pivotal concept around which social – and consequently, material – relations were arranged. Social spaces were defined “outwards” from the Brahmin body, and analysing how spaces were distributed and controlled allows us – as Lefebvre attempts – to study space as itself. As Sanal Mohan (2016, 43) argues:

Representations of space in traditional caste society were the exclusive privilege of the upper castes. They in fact conceived and controlled it. Absolute control over space in the caste order that denied freedom to the slave castes was accomplished by exerting control over their spatial mobility. Stuck in the places where they lived, in most cases on the banks of rice fields or the borders of the landlords’ farms, the immutability of space was the experience of slaves.

Yet, even as Namboodiris had controlled the representations of space (conceived space) and spatial practices (perceived space) through the caste system supported by the laws of purity and pollution, the spread of missionary activities and access of education to the lower castes provided space for the traditional structures to be challenged. Meanwhile, social-reform movements that focussed on the idea of the body as space instilled in the lowered castes communities, an agency earlier denied to them. Parallel spaces that opened up courtesy of their conversion to Christianity further redefined their perceptions of space – and thereby the spatial practices which relied heavily on the adherence to them by the lower castes. Consequently, over the nineteenth and early-twentieth-century, struggles ensued that challenged the traditional social structures. And public (social) spaces remained very much pivotal to these struggles – spaces earlier reserved to higher castes were appropriated, while new social spaces of modernity opened up that allowed for new social relations and ideologies to be introduced.

By the 1930s, Kerala witnessed a social disintegration on a scale unequalled elsewhere in India and the matrilineal systems that governed caste-Hindu relations crumbled quickly (Jeffrey 1978, 77; Nossiter 1982, 17). Traditional social order was in the decline and new social spaces were being created that drew out new spatial practices that governed social relations. Yet, the unresolved tensions with respect to gender – and specifically the attempt and a spatial divide between the domestic and public – meant that a simply reformed version of the traditional society would not suffice. The unresolved gender and religious reforms were subsequently replaced with the struggles for economic equality and social justice. It is this ideological gap that Marxism came to fill in the 1930s in Kerala. It was assumed that solving the issue of class would automatically resolve the problem of caste and gender inequalities (Menon 1992, 2705; Devika 2012). The men and women who were unsettled with the changes turned towards this ideology which appealed to thousands of literate, alienated people (Jeffrey 1978, 78). When the left-leaning Congress Socialist Party (CSP) was formed in Bombay in 1934, and its Kerala wing (KCSP) was founded by P. Krishna Pillai, E.M.S. Namboodirippad and A.K. Gopalan in the same year. The communists in Malabar at the period attempted to create a community by renegotiating rural relations while organising mass agitations for the rights of the peasants (Menon 1994, 4). In the princely states, socialism developed within a framework of the struggles for responsible government that had shaped in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Although a political front of communists also took shape in the 1930s, Marxist ideology had been introduced into Kerala’s public sphere earlier when journalist Swadesabhimani Ramakrishna Pillai wrote a biography of Marx’s life in 1912 – arguably the first book on Marx published in any Indian language (Damodaran 1975, 98). Soon, periodicals such as Bhashaposhini and Vidyavinodini published articles on the new ideals of socialism[5]. But it is in the 1930s that we see clear indications of class replacing caste as a visible social characterisation in the public sphere. More importantly, the first signs of this transition became visible in the new social spaces. A coir worker’s strike in 1933 raised the slogan: “Destroy the Nairs, destroy Nair rule, destroy capitalism” (Jeffrey 1976, 21).Three years later, when Bharatheeyan begins his speech at the first all-Malabar peasant meeting with the lines “there are only two castes, two religions and two classes – the haves and the have nots”, he was also alluding to a shift occurring in Kerala’s popular imagination – the addition of class as a category different from caste (Menon 1992, 2706).

E.M.S. Namboodirippad wrote in his autobiography, that despite having been introduced to socialism through books while younger, it was only when he started to interact with people from diverse backgrounds that a sense of public responsibility was instilled in him. The importance of the new social spaces of early twentieth-century Kerala is undeniable. The reading rooms, tea-shops and trade unions were, as Lefebvre argued, new spaces that signalled and influenced a transformation in social relations.

Early communists were quick to realise the importance of representational spaces (lived spaces) – both private and public – in communicating communism to the masses. The literate higher-caste members who were already attracted to Marxism saw such engagements with the peasant and labourers – most of whom belonged to the lower castes – as being important to win their trust. For this, they were asked consciously to break those spatial practices that had defined traditional caste hierarchies. Visiting the huts of the labourers and dining with them were revolutionary social changes that served a symbolic and a social purpose. K. Madhavan (1915-2016) who belonged to the first file of communists in Kerala, notes in his autobiography that to earn the trust of the lowered caste members in society, early communists were asked to visit the huts of the peasants, and “ask for water to drink before leaving”, to earn their trust (Madhavan 2014, 16). Such acts had a profound impact in winning the social and political support of the lowered-caste communities (Kunjaman 1996).

Soon, the communists also appropriated and used public spaces such as the village-squares and public grounds to reach out to the common masses. In as early as in 1934 when the young critics were denied a space at the main literary conference in Tallicherry, socialist P. Krishna Pillai invited Kesav Dev to deliver a speech at a Youth Conference that he organised in an open market near a kavala[6].

In his speech, Dev came down heavily on the mainstream literary sphere, arguing that it was time for the writers to move away from the palaces to write about the toiling masses, their poverty and their struggles. It was a speech that reflected the socialist ideology that was to spread quickly in the following decade, and it was befitting that it was delivered in the kavala to an eager, diverse and enthusiastic crowd. By the end of the decade, kavalas had emerged as social spaces of importance. Rifts within the KCSP after the outbreak of World War II led to socialist leaders being expelled from the party and forced to go into hiding. When the Communist Party was formed in Kerala in January 1940[7], their leaders were in hiding. However, they decided that the announcement had to be made publicly. The solution suggested by the leaders was to paint communist messages on the walls in public spaces and kavalas of north Malabar (Kunhiraman 2013, 63-64). The slogans “Long Live the Communist Party” and “May Feudalism and Imperialism Perish” that appeared on the walls and kavalas of Malabar, Travancore and Cochin in 1940-41 announced the emergence of the Communist Party, but also the secularisation and democratisation of public spaces in Kerala’s public sphere. By the mid-twentieth century, they also managed to create a strong network of new social spaces which constituted informal but vibrant associational spaces for the youngsters, predominantly male. In the second half of the twentieth century, Communist party-led trade unions, arts and cultural associations, literary and science forums all inundated the public sphere, taking communism to the common masses through theatre, music, pamphlets, lectures and stories.

Figure 1: A Kavala near Velinellur, Kerala, Picture by author, 03 July 2018

This research looks at the less formal social spaces that coexisted in twentieth-century Kerala, where informal associations formed through everyday interactions. These were not spaces maintained or controlled exclusively by the political party structures, but neither can they be brushed aside as inconsequential. Two such spaces stand out as important when one studies the case of Kerala – libraries/reading rooms and tea-shops.

3.1.

Libraries

and Reading Rooms

By the 1930s, Namboodiri students had started studying in public schools along with students from the lower castes. E.M.S. Namboodirippad, who went on to become the first Chief Minister of Kerala and one of India’s foremost Communist leaders, writes in his autobiography about how his admission to a public school in 1925 changed his life:

This was an important turning point in my life...joining school felt like beginning a new life – an environment entirely different from the one I had been accustomed to. Friends and teachers were from different castes and religions. And one didn’t study by oneself or with two or three other classmates, but in classrooms with twenty-five to thirty students” (Namboodirippad 1995, 77).

The

school

also gave him access to a reading room and library in an adjacent

building where he read books, periodicals, magazines and engaged in

discussions with peers. The

establishment of libraries and reading rooms ushered in a new space in

the modern public sphere that eventually shaped (mostly male)

mini-publics where matters of social importance were discussed and

debated[8].

It was often here – in the local reading rooms – that later political

leaders began their association with the cultural, literary and

political institutions; with the public sphere. Namboodirippad noted

in an interview that the early communist leaders made a conscious

effort to establish a reading room and a night-school in every village

by the end of the 1930s (Namboodirippad 1992).

Although the establishment of public libraries started in Kerala in the nineteenth centuries, it was by the 1930s that they had permeated into all corners of the state with the efforts of locals (Nair 1998, 175). The library movement in Malabar was slower as compared to the rest of Kerala, because British authorities were wary of political activities surrounding libraries, and tried to minimise spaces of socialising (Ranjith 2004, 10; Lenin 2017, 9; Karat 1976, 38-39). Public libraries in Tallichery, Calicut, and Cannanore were established in 1901, 1924, and 1927 respectively. Small rural libraries began to appear in villages thereafter (Bavakutty 1982, 252). Soon, plays written by communists like K. Damodaran, Thoppil Bhasi, and others that discussed the social, political, and economic conditions of the people were often staged by the libraries, generating discussions and forming public opinions. The reading rooms that were established by themselves or as attached to a library were used by the KCSP to spread socialist ideas[9].

The 1960s and 1970s were a golden period for the library movement, and the number of public libraries in Kerala continued to grow. Influenced by the left-leaning public sphere, they were centres where social consciousness was “created” and “recreated” at a rural level. As P. Achuthan (born 1945) who worked with the Local Library Authority for about four decades points out in an interview with the author:

Truth is, in almost all regions across Kerala, libraries had started functioning much before independence […] In small villages as well, reading rooms were set up. The educated people succeeded in attracting and involving others too, through public discussions, talks and interpretations of ancient texts, poetry reading, etc […] Often, libraries organised events where the local people participated in songs and theatre. The scriptwriters, directors, actors all came from among the village. These were all attempts to bring people into this [the public sphere].

Any study of the public sphere in Kerala inevitably has a section that discusses the importance of the reading rooms and libraries in forming public opinions and helping transcend political and religious differences[10]. In a sense, reading rooms epitomised the true nature of social spaces during the second half of the twentieth century in that apart from being important spaces of socialising themselves, reading rooms also facilitated other spaces where groups of people socialised in Kerala. Consequently, there emerged a number of youth clubs, theatre clubs, and associations that were attached to, and worked closely with the reading rooms. This allowed reading rooms to function as “cultural centres” of the community at large – a feature peculiar to Kerala (Bavakutty 1982, 254).

Although some of these extended spaces accommodated female participation, the reading rooms themselves remained, to borrow J. Devika’s (2013) term, “homoaesthetic circles”. In her interview, Hema (born 1973) remembers being strictly warned by her brother against going to the library as a teenager, because it “was not a space for girls to go”[11]. She defied such opposition and continued to visit the library, was the first female to apply for a membership there and was the only woman to periodically issue books at the library; reading rooms were still inaccessible to her.

The affiliated associations and clubs were relatively more diverse. A number of the respondents who were middle-aged or higher spoke of the Clubs and Associations that functioned closely with the reading rooms in their neighbourhood. Irrespective of political differences, their perception of reading rooms reflected a democratic and plural nature. This was because the spaces were conceived – since the time they were encouraged by reformers like Sree Narayana Guru, but later also under the Congress and Communist parties – as spaces where public deliberation was encouraged. Regular users also perceived these spaces as such, as Ajikumar (born 1978) recollects in an interview with the author:

It's been an active space. It is a centre of discussions and conversations. Sometimes, discussions get out of hand...like they do in our villages. We'd talk about an issue and sometimes it ends up in an argument [...] never in violence. Then it'd be resolved and they would talk about something else the next day – the same group.

This repetitive nature of public spaces is important to note. In the past, the physicality of social spaces was an important component. This meant that the groups who frequented the reading rooms and tea-shops were regulars. It encourages us to think of the influence of the increasingly “virtual” nature of public spaces. Ajikumar and his childhood friends from the reading room now have a WhatsApp group but he feels that this lacks the “personal attachment” that the physical spaces provided them.

On the other hand, they also encouraged an informal social-circle that extended to beyond the library. As Menon (1992) notes, one of the novelties of the reading rooms was the “communal drinking of tea, as one person read the newspaper and others listened. Tea and coffee lubricated discussions on the veracity of the news and of the political questions, and a new culture emerged out of the reading rooms” (Menon 1992). P. Achuthan (born 1945) comments in an interview:

When one speaks of a library in the rural areas, one must mention conversations from a tea-shop. Even after drinking their tea, people would stay around. There used to be a tea-shop next to the Desabandhu Vayanashala. People would come there for tea but the newspaper reading would continue even after the tea was done. This was when my uncle came up with an idea. There was our land nearby so he cleaned it and set up a little shed with palm leaves, put a bench and brought newspapers. So people who finished their tea could sit on the bench nearby and continue reading.

The

importance

of wayside teashops in Kerala in creating a politically conscious

working class remains under-explored. Yet, in archival research,

autobiographies of early communists and personal interviews, tea-shops

always are described as social spaces where people (almost exclusively

men) engaged in political discussions and debates. As we shall see in

the next section, they played an important role as spaces where

communism was introduced to the public.

3.2.

Tea-Shops

Tea-shops emerged in Kerala’s public sphere as representational spaces where the traditional social relations were openly challenged. Anybody with money could, in theory, walk into a tea-shop and be served tea and snacks[12]. However, most tea-shops in Kerala had emerged by the 1930s as political spaces and had an extremely influential role in shaping the public consciousness and strengthening communist thought among the common people. K. Madhavan (1915-2016) remembers the tea-shop in his village as the “central office” of political activism and political discussions for the early socialists. It was also a space where people gathered for any updates on matters of importance: “If any problem arose in the village […] people usually ran to Koman’s tea shop” (Madhavan 2014, 53). By the 1940s, the working classes and labourer in Kerala patronised the tea-shops with “stern resolve”, as tea, coffee and cocoa became increasingly popular and substitutes to local drinks like buttermilk (Pillai 1940). One observer notes of the tea-shops in Kerala in the mid-twentieth century that in his travels across south Asia, he had never seen anything like the little tea-shops of Kerala in the mornings

crowded with coolies scanning the newspapers or listening while others read them aloud. More than 40 newspapers in the Malayalam language are published in Kerala; they are read and discussed by people of all classes and castes (Woodcock 1967, 35).

As can be imagined, the presence of coolie labourers made such spaces important for communist leaders to tap into. By virtue of automatically being spaces that necessitated interaction between the different castes, tea-shops could not be controlled by upper-caste Brahmins.

The emergence of tea-shops as cosmopolitan social spaces that transcended not just caste and religion but also the limitations of spatiality reflects in a memory retold to the author by writer and critic M.N. Karassery (born 1951) from when an American academic Stephen F. Dale visited his village in the 1970s. The two heard a loud argument at a tea-shop near Karassery’s home. Karassery recalls: “I brought Dale home one day... ‘Are they quarrelling, what is going on there?’ he said to me. ‘No, no, it's a political discussion’, I said. ‘Political discussion?! What is there?’”[13].

When the two of them walked to the tea-shop nearby Karassery’s home, they realised that there were a group of people having a heated debate about the American President John F. Kennedy's daughter's name! The interesting thing is it wasn’t between someone who knows the name and someone who doesn’t but between two people who thought that they had the correct name. “Dale exclaimed – ‘My gracious!’”, says Karassery, adding, “Caroline or something is her name”. Even Dale didn’t know it. In other areas such as Mattancherry near Kochi, K.P Ashraf’s (born 1954) recollects his engagement with the foreigners who frequented the tea-shops of the area in the 1960s and 1970s. Other autobiographies and memoirs from the period also allude to the creation of social spaces that centred on tea-shops where sociabilities were transcended[14], ideas, exchanged, and opinions formed. Devika (2012) argues that the second half of the twentieth century saw a striking cultural contrast – between a literary cosmopolitanism and alarmingly conservative social attitudes. That Ashraf and Karassery’s experiences coincide with this phase suggests that a study of locally rooted cosmopolitanisms in modern Kerala must take into consideration not just the literary sphere, but also that of social spaces[15].

Babu Purushottaman (born 1957), who set up a tea-shop near the famous Paragon Restaurant in Kozhikode four decades ago, believes that the discussions and friendships he formed at his tea-shop in the 1980s drew him closer to active politics which he eventually joined: “Back then, we had crowds that would spend a lot of time as they had tea [...] not just here, really the Indian Coffee House was a left-leaning space that shaped many friendships”, he says[16]. He believes that such vibrant political engagements were common across the tea-shops in the city and is what eventually drew him closer to active politics. Kureepuzha Sreekumar who belongs to the same generation as Ashraf, Babu Purushottaman and M.N. Karassery, points out that the vibrant tea-shops[17] belonged to a specific time period of Kerala’s political history when communism and progressive ideals seemed attractive to the youngsters[18].

Over the last few decades, socio-economic factors have resulted in certain characteristic changes in the social nature of tea-shops. Babu, whose tea-shop is over three decades old, says that in the past, his customers were almost entirely writers, politicians and thinkers. Over the years, the crowd from a nearby Income tax office became regulars, although some old crowds still come once in a while. A lot of the discussions now, Babu says in his interview with the author, surround official matters – promotions, office politics, etc.

I ask them sometimes if they have nothing else to talk about. They flinch and say no. I become a listener. I focus on my work. I don't intervene. If there's a discussion on politics I intervene.

Ajikumar (born 1978) who would have belonged to the next generation of youngsters who grew up during these changes says that people across ages still use the tea-shop in his village of Poothotta near Eranakulam. However, he also alludes to a de-politicised nature of the space:

Recently the tea-shop has put up a board saying "you can't talk politics here". Because many times, this gets down to issues between people sometimes. So they put up a board saying "Please don't talk politics" (laughs). People drink tea and leave their ways [...] it doesn't get down to discussions except during election time.

He says that the regular customers are older people who drop by for tea after their morning walk when they read the newspaper for some time. For the younger crowds such as himself, he says the tea-shop is a space where they go and sit sometimes after playing, “because it's near the lake and it's nice.”

3.3.

State-Socialism

and

the Struggle for Control

The emergence of a nation-state, Partha Chatterjee (1993) argues, “cannot recognise within its jurisdiction any form of the community except the single, determinate, demographically enumerable form of the nation” (Chatterjee 1993, 238). Lefebvre argues that the state attempts to do this by seeking to master social spaces, which, “in addition to being a means of production, is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power” (Lefebvre 1991, 26). In other words, it is through an attempt at controlling social spaces – the “flattening of social and ‘cultural’ spheres – that nation-states attempt to promote itself as the stable centre (Lefebvre 1991, 23; see also Fuchs 2019). New social spaces were created in the early twentieth century in Kerala as spatiality of traditional social order was broken down. Post-independence, however, the consolidation of the state meant that there was a constant pressure on these spaces to be controlled or crushed. As Pandian (2002) notes, this contest between the state (and/or) capital and the community became an indispensable component of post-colonial India (Pandian 2002, 1738). This happens in all modern states – both state-capitalisms and state-socialisms.

In Kerala, the

struggle between the state’s attempt to control social spaces and

resistance from the communities became increasingly clear by the 1970s.

Already by then, a section of the authors,

poets, and thinkers who played an active role in the early stages of

left-politics were either side-lined by

the party or moved away from the party voluntarily. In a stark

critique of the communist parties’ weakening ties with the literary

and cultural movements at the time, Thoppil Bhasi wrote a strongly

worded article in a Party Souvenir, blaming the Communist Party for

distancing itself from the cultural movement and reminding the

important role played by writers like Thakazhi, Kesav Dev and others

in shaping the progressive politics in the state (Bhasi

1966, 171-172).

The response of the political left parties towards the radical left

movement in general and specifically to their cultural front – the Janakeeya Samskarika Vedi

(1980-82) – further widened this divide. Emerged from the radical left

movement as a cultural organisation that aimed to establish its own

cultural sphere, the Vedi attracted many contemporary poets and

artists who saw it as a space to fight for larger social issues that

the organised political left had failed to raise (Sreejith 2005; Satchidanandan

2008, 148-149). It was evident from interviews also that a

number of the left sympathisers saw this as a failure of the Communist

Party to correct its course. Ashraf from Mattancherry, for instance,

remembers that around the time he migrated to the Gulf in the 1980s,

many youngsters were disillusioned by the left parties’ stand on

social issues. This period also saw the death of many youngsters,

either from direct police brutality or suicides led by disillusionment

(Satchidanandan 2008, 149)[19];

The “secular” nature even of informal associations was affected by excessive political intervention by the late 1980s. One of my respondents, Hema (born 1973) recollects that by the 1980s, the Arts Club near her home had split into two groups based on political differences and eventually, both shut down. Other younger respondents such as Sreerag and Jitheesh (both 25 years old) said that people their age group were not involved with Clubs in their respective villages because they were being hijacked by political parties. Jitheesh said that there is one Club near his home, but he wasn’t interested in joining it because its members – all aged under thirty, he said – are members of the DYFI and “they go to stick posters [for the party]”.

4. Capitalism,

Communalism, and Social Spaces: The 20th Century and

Beyond

Even as communist forces struggled to resolve the contradictions of social spaces that had emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, economic and social changes as a result of both internal and external factors led to a radical redefinition of spatiality towards the end of the twentieth century. Capital emerged as a major player after the liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, leading to a rapid increase in urbanisation and privatisation of land. Also important are the economic changes that the Gulf boom brought to the purchasing power of the people, and the rapid growth of the culture industries which had already emerged since the sixties. Meanwhile, the spread of satellite television and media changed how news was consumed in Kerala, radically affecting the role of rural libraries, teashops and reading rooms as social spaces (Ranjith 2004, 14).

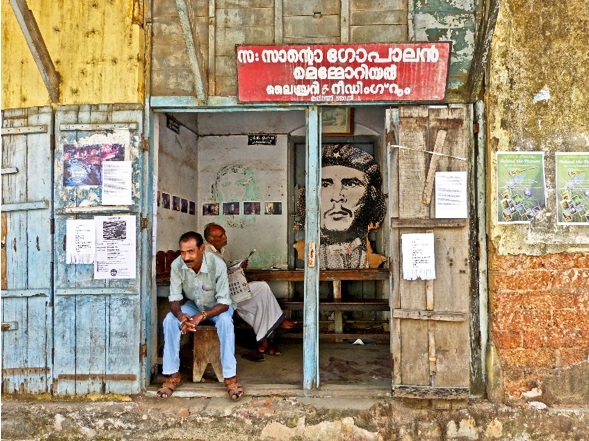

Figure 2: Once active spaces for everyday political discussions among the youth, reading rooms have ceased to attract youngsters today, as news is increasingly “consumed”, not “engaged with”. Seen here, Comrade Santo Gopalan Reading Room and Library, Fort Kochi. Picture by author, 16 January 2017.

In the twenty-first century, the decline in conventional social spaces, along with the increased control of spaces by capital and religious forces has led to new challenges to the left. Responding to these changes in the 1990s, the left saw decentralization of power as the most effective way to combat narrow religious and communal interests and global capital. Consequently, the meaning of civil society was revised to accommodate broad alliances at the grassroots level that cut across religious, caste and gender differences.

This led to a new struggle, since on the one hand, they created autonomous civil societies at the local levels, while on the other, capital and religious spaces also multiplied like never before. Even as autonomous secular social spaces emerge, the secular response to these challenges has been two-fold and unconvincing. On the one hand, there was an attempt to dissociate from the religious in the cultural sphere. The left’s attempts to uphold the secular ideal have been met, on the other hand, by instances where the Community Party resorts to over-accommodation of religious sentiments, rituals and practices. For instance, the celebration of “Krishna Jayanthi” (a religious festival celebrating the birth of Hindu god Krishna) in 2016 under the guise of Onam (secular harvest festival which, although with Hindu rituals and myths, is celebrated across the religions of the state) celebrations had drawn severe criticism to an extent where it “alienated true comrades from the party”[20]. The CPI(M)’s rallies on the day have attempted to rival the right-wing Hindu nationalist organisations’ “Shobhayatra”s which continue to draw large crowds (see Figure 3)[21]. In another instance, one of the CPI(M) processions came under a row after it featured Thidambu Nritham, a temple ritual[22]. The unsaid rule of the communist party has urged its cadres to involve culturally” in temple festivals, while State Committee members have been asked to dissociate from going to temples[23].

Figure 3: The Shobha Yatras started in the 1980s by right-wing cultural organisations continue to draw large crowds. Seen here, the Yatra at Thrissur city. Picture by author, 12 September 2017.

But these moves have come under criticism from the public across political ideologies. Criticising this attempted renaissance political analyst N.N.Pearson states: “How can a party that has diluted its own ideology for the sake of power lead a renaissance campaign? The politically enlightened people of Kerala can see through the games”[24]. Even in the 1990s, the equation of religion and politics came to become an important one to address.

In 1997 – a decade after the CPI(M) laid out a policy that their only God was the ‘Red God’ – the then Communist Chief Minister Nayanar’s meeting with the Pope became a matter of much debate within Kerala. Opinion pieces were written criticising the gesture and to them, Nayanar quipped that the meeting was going to neither make the Pope a Communist nor make himself a non-Communist and that the matter needn’t be blown out of proportion[25]. Such tensions continue to persist into the twenty-first century, as many cases from the recent past – including the agitation against a caste-wall in the temple at Vadayampady, the controversy following the Supreme Court verdict allowing women of all ages entry into the Sabarimala temple which earlier had age restrictions of women, etc. show. As has been mentioned, these add to the ever-rising concern of creating secular progressive spaces despite the internet and media providing alternatives to the common masses.

5.

Conclusions

Social spaces played an

important role in helping early communists to reach out to the masses

and in shaping a progressive public consciousness. Unlike

institutional spaces that are maintained and work under rigid party

guidelines, informal spaces like reading rooms and teashops enjoyed an

autonomy that allowed them to create a broader network of people

cutting across party differences. A rigid party structure, the CPM’s

failure to accommodate for alternate social spaces that emerged in the

1980s and a rapid change in the economic and social systems have

radically reformed the spatiality of Kerala in the twenty-first

century. The increase of capital and religion in the public sphere

raise new challenges to the secular and progressive forces. This leads

us to the question: What can the communist parties do to meet the

challenges raised?

In Lefebvre’s argument about the transition from social-democracy to

decentralised state forms in contemporary times, he urged the

political left to explore the potential of autogestion

in asserting a counter-hegemonic use of space, since it is the

“one path and one practice that may be opposed to the omnipotence of

the State” (Lefebvre 2009, 134; see also Butler 2010, 100). Lefebvre saw autogestion

– most closely translated as grassroots democracy – as an essential

basis for the democratisation of society, born spontaneously out of

the void in social life that is created by the state (Lefebvre

2009, 14-15). To him, it was the radical democracy that emerges

with the withering away of the state in modernity.[26]

It is a redefinition of the state as an arena for “spatial autogestion, direct democracy, and democratic control, affirmation

of the differences produced in and through that struggle” (Lefebvre

2009, 16). Although such movements may not have the continuous

character and institutional promise of parties or trade unions, a

decentralised state, Lefebvre argues that they have the power to

reconstruct social space from “low to high”, as opposed to “high to

low”; social needs would be determined here by the action of

interested parties, and not by “experts” (Lefebvre

2009, 193).

The ultimate aim of progressive movements must be to expand radical

democracy to the deepest tiers of society. For this, they must aim not

at narrow conceptions of controlling social spaces but must facilitate

the creation of wide networks at the grassroots that may succeed in

successfully challenging any attempts at control from above.

In other words, Lefebvre’s work on decentralisation and autogestion can provide useful insights into understanding how communication strategies must change in contemporary societies. In Kerala, the autonomous, secular associational spaces at the grassroots continue to provide progressive, issue-based social spaces where people can come together outside the “rigid structures” of party politics. The attempt must be to nourish such spaces without succumbing to the pressures to react to narrow religious pressures.