Politically, the broad masses only exist insofar as they are organized within political parties. The changes of opinion which occur among the masses under pressure from the determinant economic forces are interpreted by the parties, which first split into tendencies and then into a multiplicity of new organic parties. Through this procedure of disarticulation, new association and fusion of homogeneous entities, a more profound and intimate process of breakdown of democratic society is revealed. This leads to a definitive alignment of conflicting classes, for preservation or for conquest of power over the state and productive apparatus (Gramsci 1921, in Forgacs 1999, 121-122).

Gramsci’s statement, which first appeared in L’Ordine

Nuovo on 25 September 1921, accurately describes a process of disarticulation that

– in other forms – has been representative of the distinctive

character of the

transformation of political partiesGramsci himself had been developing

the idea

of the party as a collective intellectual, an element of a complex

society in

which the concretization of a collective will is recognized and

partially

established in action (see Gramsci Prison Notebook 13, 1; now in Forgacs

1999, 238-243). The party, in this sense,

carries out an educational function and political direction of the

class it

represents: this function is possible only because the party is a

“collective”.

The processes of parties’ transformation – and in particular those of the socialist tradition – have made the collective dimension marginal, favouring the aggregation of individual requests. In this scenario, digital technologies can play different roles:

a)

they can

function as mere tools to support consensus building;

b)

they can

become organizational facilitation tools;

c)

they can

constitute a terrain of political struggle for hegemony;

and,

finally,

d)

they can

promote the development of a new digital socialism, also helping to

re-connect

people with politics. However, these roles are not always necessarily

alternative.

This article aims at discussing the role of digital technologies in the political life of some European left-wing parties and in the organisational models of radical left social movements. In particular, here we present the first findings coming from the study of policy documents on digital technologies produced by some socialist/labourist/left-wing parties and the very first considerations taken from some of the many in-depth interviews with digital activists of a number of social movements.

In the following

sections

we will try to shed light on: a) the role of socialist parties in the

framework

of transformations of representation, trying to identify the

relationships

among intermediate bodies, processes of depoliticisation and development

of the

so-called post-representative politics (section 2); b) the role that

technologies play in these processes and, in particular, how the

techno-enthusiasm forms are functional to a capitalism with a human face

but

still hardly neoliberal (section 3); c) the role of platform parties on

the one

hand and digital technologies for communication as different outcomes of

political re-organization processes on the other hand (section 4); d)

the role

and function of social movements in the emergence of new forms of

re-politicisation which is indispensable for the emergence of a new

digital

socialism.

2.

Political

Parties

in a Post-Representative World

The many different theorisations of

representation (Pitkin 1967; Brito

Vieira and Runciman 2008; Pettit 2009;

Saward 2010)

choose different perspectives. Both the bipartition between Pitkin's (1967) standing for and acting for, and the

new

perspectives, which are less focused on a binary

logic,

seem in part unfit for interpreting the change in the dynamics of

relations

between representatives and represented, in particular in the scenario

of the

media politics. The different theorisations, however, keep open the

old

question of political representation and its relationship with liberal

democracy. The mandate of the elected can only be free (since assuming

a

delegation contract means making the individual's autonomy disappear)

but, at

the same time, the elected must place themselves in the position of

being

controlled by the voters. In other words, representatives play an

active role

(legislative function) and must therefore enjoy a certain autonomy,

being

capable of going beyond the electoral exercise. At the same time,

precisely

because of this role, they must in some way “depend” on the

electorate. The

paradox is evident: if the representatives had an imperative mandate,

they

should only respond to a client (theoretically plural, in practice

traceable in

the leader) or respond only to themselves (and in this case they would

be

totally released from any control). That is, representative democracy

works

only if we avoid an opposition between imperative mandate and free

mandate

(Urbinati

2013),

making sure that the latter is tempered by some form of popular

control. The

political mandate, in other words, still needs parties (or similar

organizations), as explained very clearly by Nadia Urbinati (2013,

99).

Representation has a very strong connection with another concept that cannot be underestimated: citizenship. Representation, in effect, is a relationship between a social group and a representative who shares the group’s interests, expectations, values, problems, territorial emergencies and so on. It can be affirmed, at this point that without social inclusion – made possible by the logic of political representation or similar processes – citizenship does not even exist and therefore that no representation can exist without representation. It is a syllogism not without ambiguity but substantially correct.

One of the outcomes of the democracy of organised distrust is represented by the emergence of new forms of social surveillance and political militancy. Among the latter, significant positions belong to advocacy groups, expressions of active citizenship (Moro 2013), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), observatories on specific issues and campaigns (in many cases organized through digital platforms) and the results of actions in the territory (such as the Stop-TTIP, No-Ceta, etc. campaigns). In many cases, these organisations (campaigns first and foremost but also different advocacy groups) do not “represent” in the traditional sense, do not have membership structures, and are mostly single-issue (i.e. oriented to a specific cause). They carry out activities of influence and, in some cases, activities of lobbying (Ceccarini and Diamanti 2018, 351). In light of new organised forms, representative democracy seems to give way not only to counter-democratic demands but also to what John Keane (2009) calls monitory democracy. A monitoring carried out both through lobbying practices and through the legitimization of tools coming from the tradition of deliberative democracy (Elstub and McLaverty 2014), such as citizen juries, deliberative polls, city assemblies, online consultations, petitions, and finally through organizations for monitoring and protection, such as consumer movements or associations for human rights. The Internet constitutes a “workplace” that facilitates the emergence and rooting of these experiences, although it does not constitute an activation element.

The monitorial citizen (as in the expression of Michael Schudson [1998]) tends to effectively replace both the citizen voters and even the critical citizens (Norris 1999). In this new scenario, representative democracy – based on a direct relationship between citizens and legislative assemblies – gives way to post-representative politics (Keane 2013), in which citizens can experience forms of creative activism that are not always consistent with the traditions of political representation through party organizations.

At this point,

we already

have some critical elements. We have probably entered a political phase

that

can actually be defined “post-representative”, in which forms –

sometimes very controversial – of “direct

representation” (De Blasio and Sorice 2019)

emerge. At the same time, the institutional fabric of liberal

democracies is

still based on the mechanisms and logics of representation. Hence the

need to

consider political parties is inescapable, although their credibility

and their

own social legitimacy have been severely tested both by economic crises

(Morlino and Raniolo 2018) and by the

(alleged)

crisis of institutional representation. This is an almost paradoxical

situation

that has affected, however, most severely those parties that had a

strong

organisational root and were deprived of both their social legitimacy

and their

ties to the territory in one fell swoop. In this framework, the parties

inherited from those of mass integration – essentially the parties of

the

socialist / social-democratic and communist tradition – were the most

affected,

precisely because their “heavy” organisation did not lend itself to

transformations that were too rapid.

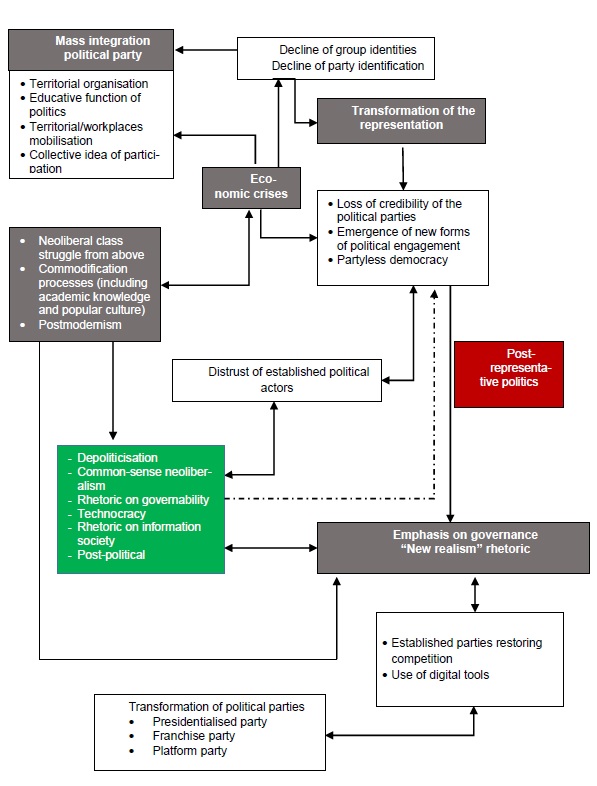

Figure 1: Political parties, depoliticisation and post-representative politics

However, we must also consider some

forms of

political dealignment that have affected the socialist/labourist

parties. The

use of the discursive strategy of economic “realism”, for example, has

certainly represented an element of criticality. This aspect, however,

had

already been noted by Stuart Hall in 1988, when the expression “new

realism”

was used to indicate a substantial transformation of the Labour Party,

capable

of aggregating electoral consensus but not activating “sentimental

connection”:

It [the Labour Party] can mobilize the vote, provided it remains habitually solid. But it shows less and less capacity to connect with popular feelings and sentiments, let alone to transform them or articulate them to the left. It gives the distinct impression of a political party living on the capital of past connections and imageries, but increasingly out of touch with what is going on in everyday life around it (Hall 1988, 207).

A simplified graphic representation

of the

transformation involving the mass political parties is presented in

figure 1.

It is evident how different factors influence or have a role in this

transformation. At the same time, it is useful to note that these

transformations could be better understood if we study them in the

frame of

neoliberal ideology’s rising. The emphasis on technology and on the

insurgence

of the “information society”, for example, are the outcomes of a

neo-capitalist

approach and the left-wing parties across Europe have under-evaluated

the role

of communication in the intricated relationships among state, market

and social

actors, as clearly stated by Dallas Smythe more than forty years ago (Smythe 1977)[1].

3.

Political

Parties

Between De-politicisation and Digital Enthusiasm

Moreover, over the last thirty

years

storytelling about overcoming the “old” categories of right and left has become hegemonic, to the

point of being

considered a trait of cultural “modernity” and even scientifically

based. The

idea that the political categories of right and left were outdated was

preceded

by the development of a broad literature on the “end of ideologies” (Fukuyama 1992): several positions developed

within it,

some more distinctly technocratic, others that identified in the

development of

shared deliberative processes and in the affirmation of collaborative

governance the only elements necessary for the qualitative increase of

democracy. The success of economic approaches such as that of the

Chicago

School or of paradigms such as New Public Management has favoured the

legitimacy of these positions.

The beginning of the 21st century, however, has been characterised by various phenomena:

a) the revival of nationalisms and religious fundamentalisms;

b) the explosion of the economic crisis of the Western world, that was generated precisely by those economic recipes that had achieved media and political success but proved to be unsuitable for solving the structural problems of the world economy (Crouch 2011);

c) the rebirth of the various populisms and the emergence of the “challenger parties” (mainly right-wing), often connected precisely to the criticism of the liberal system;

d) the onset of several popular protest movements, which attacked the outcomes of liberal democracy precisely by demanding more participatory political processes and, generally, “more democracy”.

This last aspect, in particular, has brought to light the democratic short circuit: not only the historical inconsistency of the alleged overcoming of right and left but also the apparent paradox of a criticism conducted towards liberal democracy because perceived as being rather insensitive to requests for people participation.

The processes of de-politicisation have been studied by different authors (Mouffe 2005; Rancière 2010; Žižek 1999) with components that are sometimes different but always referable to the idea of a substantial loss of centrality of politics as belonging and project: in other words, politics has often been reduced to only a dimension of policy, with a substantial marginalization both of the ideological conflict and of polity as a project community.

Colin Hay (2007) has clearly highlighted the relationship between the so-called anti-politics, the tendencies of the resurgent populisms and some aspects of the neoliberal turning point. The process of depoliticisation has thus been framed within the development of complex social phenomena, some of which underpin the post-political tendency that seems to have characterized the last decade of Western democracies. In this scenario, we can see how some of the political-institutional innovations theoretically oriented to the growth of participation (such as, for example, the experiences of collaborative governance, some variations of e-government and different public consultation tools) have been absorbed into internal trends of substantial anesthetization of any forms of social conflict and, in general, of popular participation.

In fact, these innovations have proved to be mechanisms of political legitimisation for the political élites, obtaining on the one hand their own failure with respect to the objectives (increasing the amount and awareness of popular participation) and on the other hand, their rejection by the popular classes that have interpreted them (not without some reason) as “top-down” tools also perceiving them as strategies of the élites. To the forms of innovation – often however supported in good faith by local administrations and scholars – some institutional reforms have been added, and are often used as tactics and tools for the affirmation of a post-political neoliberal projects (Flinders and Buller 2006). Both institutional reforms and some experiences of democratic innovation have thus turned out to be “mechanisms used by politicians to depoliticise issues, including delegation, but also for the creation of binding rules and the formation of discursive preference shaping” (Fawcett et al. 2017, 5)[2].

In this situation, the semantic shift from the idea of “government” to the notion of “governance” should also be considered: it constitutes one of the elements that accompanies the emergence of the so-called “post-political” and of the reduction of politics to only economic concerns.

These post-political tendencies are outcomes of the depoliticisation, and they have been very often accompanied by the phenomena of re-politicisation within the rhetoric of “governability”. This last component has been often wrapped in a “common sense neoliberalism”, fed by the rhetoric on the “light state”, that of efficiency[3] at the expense of the quality of democracy and of the commodification of citizenship (Crouch 2003). The “common sense neoliberalism” that emerged in the late 1990s could be contrasted only re-discovering the educative role of politics. “Politics, as Gramsci insisted, is always ‘educative’. We must acknowledge the insecurities which underlie common sense’s confusion and contradictions and harness the intensity and anger which comes through in many of the readers’ comments” (Hall and O’Shea 2015, 65).

On the other hand, the insurgence and development of digital technologies

for communication have deeply changed the scenario. The old

techno-libertarian

tendencies of the sixties re-emerged, merging with the (fundamentally

technocratic) rhetoric of technology as an instrument of

democratization of

capitalism and of improving administrative efficiency. The new

“participatory

culture” (Fuchs 2016, 87) would also be

capable of

replacing elective assemblies and giving more (presumed) power to

citizens.

This techno-enthusiast ideology is an “expressions of the capitalist

fetishism

of technology that Marx criticised” (Fuchs 2016,

207).

In this way,

digital

technologies have entered the imaginary at two levels: the first level

is a

hyper-optimistic techno-enthusiasm that has fundamentally considered the

digital as a shortcut to recover the participation that had diminished

in the

territory; the second, more critical level, has identified in the

digital

technologies the tools for a technocratic control of the organization of

the

State and of political life.

4.

Towards

the

Platform Party

Very often digital technologies

and, in

particular, their applications to the e-government have been

functional to the

New Public Management approach (De

Blasio and

Sorice 2016), activating an ideological transformation of the

“public”

(perceived as old) in the efficiencyst idea of the state-company (Crouch

2011; Sorice 2014).

There are also many parties of different orientations which adopt platforms of democratic participation: significantly, however, the wealth of possibilities for online deliberation remains confined to a few exceptions.

The thesis that the Internet would have led to the emergence of claims and the development of political movements from the non-leading horizontal structure does not actually find empirical confirmations but has instead been contradicted by numerous studies. In a rather hasty manner, digital activism was considered to be the characterizing aspect of the new political movements and to be the outcome required of digital media; in fact, many studies have shown that movements with a strong online presence have at least as strong a presence within a territory (Kreiss 2012; della Porta and Rucht 2013). Another common place idea is that the movements would always be horizontal, without a hierarchical structure and without a leader, by virtue of the fact that they would borrow not only the dynamics of transmitting messages but also the modalities of the adoption of decisions. In fact, in the study conducted by Donatella della Porta and Dieter Rucht (2013), diversified forms of power and conflict are also identified in the global justice movements, while Paolo Gerbaudo (2012) spoke of a “choreography of the assembly” in which the collective dimension of the protest is organised and staged by an elite group of activists. These frame elements are useful for understanding the scenario in which both the forms of online participation “from below” and the so-called platform parties are born and develop.

The studies on platform parties are the result of a long reflection on the transformation of the political parties. From the classifications of Duverger (1951) to those of Kirchheimer (1966) up to the fundamental work of Stein Rokkan (1970) to finally the analysis on the emergence of the “cartel parties” (Katz and Mair 1994), various studies on the organizational form of the so-called intermediate bodies have taken place. The development of personal, presidentialised, liquid-presidentialised parties (Prospero 2012) and even franchise-parties (Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel 2014) have marked the last decades, framed by the crisis of legitimacy of the traditional parties. The rhetoric of participation (“participationism”) has also accompanied the emergence of new organizational forms of politics, although such rhetoric has been reduced to a generic “openness to society” and programmatically refuses an internal organization based on deliberative and participatory logics. In this context, even the use of primary elections (in small as in large scale) responds to a rhetoric of participation but often ends up being just a tool for legitimizing the party elite. The accentuation of the refusal to participate or a distrust in politics and, in particular, in the political parties by the citizens is not surprising in this context

Very often it was thought – in a somewhat naive manner – that to favour participation and to increase the internal democracy of a party it would be enough to enlarge the selectorate of the party itself[4]. In reality it is not enough to enlarge the selectorate, as is evident from the crisis of credibility (and sometimes even legitimacy) that has hit the traditional parties – and often precisely those with more deep-rooted popular traditions – in the Western representative democracies over the last twenty years

One of the responses to the representation deficit – and to the related refusal of participation through the only electoral delegation – has come in recent years from the adoption of communication technologies, in particular those connected to the Internet and, more generally, to the opportunities offered by the development of democratic participation platforms (De Blasio 2018). In many cases, these technologies have been framed as neutral tools, but “far from being considered only as tools, media and communication technologies have become a site of struggle in their own right, and as such are subject to object conflicts” (Hess 2005, 516, cited in Milan 2013, 2).

In this

scenario, we have

been focused on the rise

of the

so-called platform party (also defined as the “digital party”[5]). This type of party finds

new

organisational methods in Internet tools and in participatory platforms.

Platform parties are born from participative logic. However, in many

cases they

are revealed as results of the hyper-representation phenomena. The

leader (the

supreme representative of all the people) creates a symbolic connection

with

the super-people (the superbase in the analysis of Gerbaudo [2019]),

the one represented by the active people in

platforms of digital participation. The participation evoked in this

type of party

is of a dualistic nature. The emphasis on direct democracy, however,

often

delegitimises any form of participatory democracy. There are obviously

many

types of the platform party and they are affected by national

peculiarities and

electoral systems. However, they are a response to the growing popular

need for

participation, albeit in intermittent forms and with a personal and

daily

commitment (Ceccarini and Diamanti 2018).

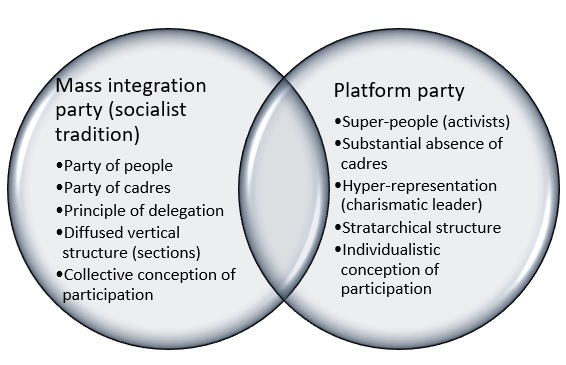

In

essence, platform parties use technology as an organisational mode and

as a

structural architecture. At the same time, they use digital

participation

platforms as mobilisation tools, as spaces for policy making (the

presentation

and discussion of proposals) and as places for decision making (voting

on

proposals and policy decisions). In some cases, a platform party can

also take

on a stratarchical type of structure.

Figure 2: Characteristics of the mass party and

of the platform party.

Technologies

respond

efficiently to three different tendencies of contemporary politics. In

fact, they can:

a) influence the organizational models of participation;

b) accelerate the processes of deconstruction of intermediary bodies;

c) feed the perspective of liquid democracy (a really controversial concept, usually overlapping with that of “delegative democracy” – a merging of representative and direct democracy – based upon the use of digital platforms, such as, for example, LiquidFeedback[6]).

These three tendencies are not

necessarily opposed to each other. Digital technologies, in fact, can

contribute to the deconstruction of the “old” intermediate bodies and,

at the

same time, favour new organisational model of participation that are

at the

background of new party structures. At the same time, the so-called

“liquid

democracy”, and, in general, the use of digital participatory

platforms can

activate new forms of participation but also contribute to a radical

change in

the party’s organisation. Digital technologies

can be tools for: a) mobilisation, b) policy making, c)

decision making.

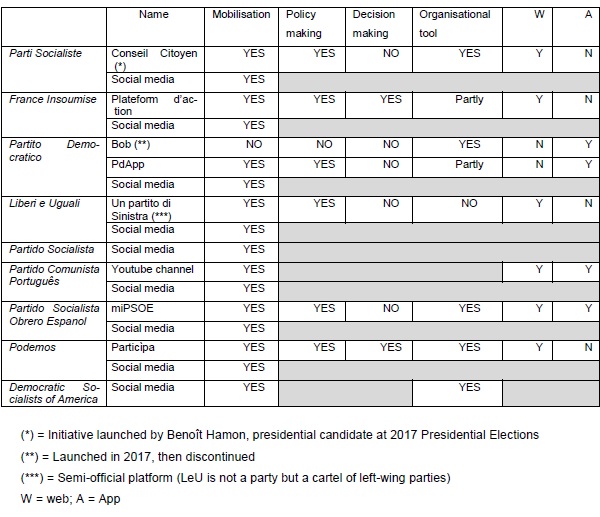

Table 1. Political parties analysed.

Following

this

simple taxonomy, we have been studying the use of digital platforms by a) parties inspired by socialism in

Italy, France, Spain, Portugal and the USA; b) bottom-up social

movements. The

analysis has been framed in an empirical approach based on the

analysis of

organisations on the one hand and on the content analysis (Evaluation

Assertion

Analysis) of the political and/or policy documents on the use of

digital as a

tool for political struggle.

The analysis has been conducted in

respect

to the political parties listed in Table 1.

The Democratic

Socialists of America have been considered only as a “control

variable”. Any

comparison with the left-wing parties of Southern Europe is in fact

almost

impossible[7].

Table 2: Tools used by political parties for functions and type

The

first

element to underline is the substantial absence of co-ordinated

digital

actions. Mostly, the tools are functional to mobilisation practices

and work

essentially as elements of support for political communication.

Democratic

platforms of participation are constitute a minority in the total

number of

technologies employed. In the Iberian peninsula there are the most

radical

developments: on the one hand, the use of digital technologies has

taken root

in Spain thanks to the success of Podemos

(Caruso 2017) and the ability of the Partido

Socialista

Obrero Espanol (PSOE, the Socialist Party) to intercept a demand

for innovation. Podemos was over time transformed from a

party-platform to a

party that uses a platform; PSOE, tried to use social media and its

app (and a

web-based platform too) as tool of a counter-storytelling to offer a

partly different

answer to Podemos.

On the other hand, there is Portugal (a country in which, moreover, there are many platforms for participation for civic uses) where left-wing parties (winners of the 2019 political elections) seem to devote more energy to activity in offline space and the (very active) use the dominant social media platforms. In particular, the Socialist Party uses Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, has a YouTube channel and even a Pinterest account; the Communist Party uses Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, has a YouTube channel and also WhatsApp as source of information (similarly to how PSOE in Spain uses a Telegram channel).

In France, the “participatory programme” experiments launched by Benoît Hamon in 2017 did not find a follow-up in the Socialist Party's projects (perhaps due to the party's electoral decline). However, the platform launched by France Insoumise moves from the level of mobilisation to spaces where concrete proposals are developed and active deliberation processes take place. At least in part the platform is an aspect of France Insoumise’s organisational modality[8].

There is a substantial absence of specific documents and policies on the use of digital technologies, above all at the organisational level. This seems apparently contrasting with the parties’ effort to activate consensus and mobilisation through social media[9].

Greater attention seems to be given to digital participation in Italy, where, however, the socialist-inspired parties have not had (at the moment) great successes in the adoption of digital technologies: alongside social media – a “continuous bass” of all parties’ communication activities – there are only the apps produced by the Democratic Party (but not a web platform[10]) and the interesting but unsuccessful attempts of the Liberi e Uguali (LeU, Free and Equal) platforms (and even before that of Sinistra Italiana-Italian Left, one of the small parties that then gave life to LeU in 2018) .

In none of the

parties

under analysis – at least in the official documents concerning the use

of

digital and its relations with political organisation and with the

exception of

the Portuguese parties – there are references to the use of a Marxist

(or

post-Marxist) perspective on technology and communication, although in

Marxist

theory there have been many reflections on this topic from the first

stage of

Cultural Studies, to some approaches of political economy of the media (Smythe 1977), until the most recent

perspectives of the Marxian

study of social media and digital technologies and, more in general, of

Internet studies. A very comprehensive and accurate overview of the

Internet

Studies in a Marxian perspective is available in Fuchs and

Dyer-Witheford (2012; see also Fuchs

2014, 73)[11].

Different perspectives are present in

the area of social movements and, in particular, in those positioning

themselves “on the left”. Both in the first interviews conducted with

the

activists of various social movements and in the results of similar

research

that we have conducted over the last three years, a different

awareness has

emerged with respect to the role of digital communication

technologies. Along

with positions of suspicion towards communication (which appear

minoritarian

anyway), there is growing awareness that digital ecosystems are spaces

for

struggle, as we will try to argument in the next section.

5.

Digital

Socialism:

A Challenge for Social Movements and Political Parties

The crisis of legitimacy of the

left – and

especially of the socialist/labourist and/or social-democratic parties

–

derives from many factors, not least their acquiescence to the

economic

dictates of neoliberalism and the progressive marginalisation of

themes such as

socialism, social justice, equality, and the democratisation of

society in

their political programmes and agenda. The complex question of the

cleavage of

the sentimental connection (Gramsci, Quaderno XVIII, now in Gramsci

1971, 135-136) between parties that stand in

the socialist tradition and the popular classes constitutes one of the

most

important points of discussion among scholars and also politicians.

The new

tools of democratic participation represent a great opportunity for

developing

dynamics of inclusiveness. It is not enough to adopt the structure of

the

party-platform. Rather, instead, it would be useful to merge the

dimension of

the net (as a tool) with a territorial presence in the offline world

capable of

starting from the needs of society.

One of the elements that left-wing parties have not always understood is that there is no contradiction between the practices of digital democracy and the processes of participation in territorial realities offline. Digital participatory platforms can be used alongside “apps” for facilitating the involvement of citizens and activists. A greater territorial involvement can in turn determine the growth of active individuals online and offline, creating a virtuous circle of participation that may be intermittent but not occasional. In this perspective, digital platforms can offer tools for mobilisation, can act as spaces for facilitating policy making and, finally, they can favour the adoption of more democratic decision-making mechanisms.

Mobilisation, shared formation of public policies and decisions taken with a democratic method are characteristic and peculiar elements of the socialist tradition. Digital technologies can be extraordinary tools for rooting and spreading socialist values. It is necessary to place communication technologies and architectures within shared rules of transparency and to enable democratic access in order to avoid the drift of the platform parties that preach direct online democracy to erase participatory democracy and the development of a real egalitarian democracy. In other words, it is necessary to remember that technologies are not neutral and their use – in one sense or another – is a political act. Adopting these technologies to the logic of online deliberation, for example, and not to the aggregative logic of online direct democracy (Mosca 2018), would mean, moreover, empowering the voices of the people who are without voice and often without representation. But also the risk of the “platformization” of society is very strong (van Dijck, Poell and De Waal 2018).

Probably the most lively and plural area in the political use of digital technologies is that of social movements. In this area – as effectively noted by Stefania Milan (2013) – different ways of using communication technologies can be identified. It is no coincidence that also in the academic field different definitions have been used, often partially overlapping, sometimes clearly distinct: in fact, alongside the use of the expression “media activism”, we find works that can be framed in the field of “alternative media” or even “non-mainstream media” (Pasquali and Sorice 2005), or those that refer to the effective category of “emancipatory communication practices” (Milan 2013), or as well as those that tend to relate media research to the studies on democratisation.

In our analysis, we found very different experiences of social movements, which in some cases have developed bottom-up democratic innovation practices: from civic engagement groups (halfway between social movements and active citizenship practices) to one issue pressure groups that also carry out lobbying activities without necessarily acting as interest groups (as in the case of Stop-TTIP movement[12]). The examples include fair trade organisations, struggles for housing rights or for “riders’ rights”. They have some common characteristics, such as a participatory and non-centralised organisation (della Porta and Rucht 2013, 2), a polycentric and inclusive organisation, and the production of knowledge about digital capitalism (Pavan and Mainardi 2019). Such movements are agents of democratic communication. This last point is very important for our purposes because these movements adopt democratic practices that are not limited to the logic of representation. At the same time, social movements can be defined by referring to the fact that: 1) they are mainly informal interaction networks; 2) they have shared beliefs and activate dynamics of solidarity; 3) they mobilise around conflicting issues; 4) they adopt various and differentiated forms of protest, often of a “creative” type (Micheletti and McFarland 2016) and very often use digital technologies as tools and spaces of struggle.

This last point is very important because digital tools and more generally communication practices play a key role in social movements. Donatella della Porta (2013, 92) notes that

in recent reflections linking communication and participatory democratic quality, the focus of attention is not so much (or no longer) on the abstract “power of the media”, but more on the relations between media and publics: the ways in which “people exercise their agency in relation to media flows” (Couldry 2006, 27). Media practices therefore become central, not only as the practices of the media actors, but more broadly as what various actors do in relations with the media, including activists’ media practices.

One of the respondents in our

interviews

argued in this context:

The point is not to use social media or not; it is clear that those are for profit and are functional to the logic of capitalist accumulation […] they impose their ideology [..]. They are spaces to be used tactically. But at the same time, we should try to organise alternative spaces of struggle, but this is only possible in an international perspective (F, 27)

There are several interesting

experiences

that go beyond the contrast between mass integration parties to which

almost

all socialist political parties belong and platform parties. Social

movements

are interesting field of social research. They could also constitute

an

important site to re-connect media studies with the Marxian approach that was too hastily

abandoned in the second

half of the 1980s by postmodern and culturalist approaches.

6.

An

Open

Conclusion

We must admit that we are unable to

provide a

clear answer on the use of digital communication by different

collective actors

such as political parties inspired by socialism and radical social

movements.

Some of the data is contradictory, so more research is needed. The

transformative dimension of capitalism makes exhaustive analysis

difficult. The

very transformative nature of capitalism has allowed the use of

expressions

such as “digital socialism” on the part of the “owners” of

media/technology

companies (Morozov 2019). In many cases,

capitalism

“with a human face” has offered spaces that are economically

profitable and

that digital capital presents as democratic achievements but that

given their

subsumption under capital have a limited potential as spaces for

struggle.

Neoliberal ideology has succeeded in incorporating tools and

experiences of

online participation. Platforms of participation have often become

instruments

of mere consultation used by capitalist organisations and

bureaucracies so that

digital technologies are reduced to function as tools that make

capitalism and

public administration more efficient. This is the perspective of the

New Public

Management approach that does not aim at providing spaces for

citizens’

democratic participation.

There are three reasons why left-wing parties have not managed to come up with alternatives: 1) there is an organisational similarity among these parties that produces the homogenisation of perception and the idea that old structures cannot be modified; 2) participation is practiced and understood in manners that do not really encourage participation, but only promote engagement; 3) there is a weakness of deliberative processes. A further hypothesis to test is that the model of online participation is so steeped in digital capitalism that it leaves no way out.

In this

scenario,

left-wing parties do not yet seem to have succeeded in providing an

alternative

framework for digital communication that goes beyond digital capitalism

and,

sometimes, do not even understand the importance of communication not

just in

the transformations of capitalism

that

have resulted in the emergence of digital capitalism but also in and for

a

renewed socialist project.

References

Albertazzi, Daniele and Sean Mueller. 2013. Populism and Liberal Democracy: Populists in Government in Austria, Italy, Poland and Switzerland. Government and Opposition 48 (3): 343-371. DOI: 10.1017/gov.2013.12.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge:

Polity.

Brito Vieira, Monica and David

Runciman. 2018. Representation.

Cambridge: Polity.

Caruso, Loris.

2017. Reinventare la

sinistra.

Le basi politiche, culturali e organizzative di Podemos. Comunicazione

politica,

Quadrimestrale dell'Associazione Italiana di Comunicazione

Politica

1/2017: 31-54, doi:

10.3270/86128.

Ceccarini, Luigi and Ilvo Diamanti. 2018. Tra politica

e società. Fondamenti,

trasformazioni

e prospettive. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Coleman,

Stephen and

Jay G. Blumler. 2009. The Internet and Democratic

Citizenship. Theory, Practice and Policy. Cambridge:

Cambridge University

Press.

Crouch, Colin. 2013. Making Capitalism Fit

for Society. Cambridge: Polity.

Crouch, Colin. 2011. The Strange Non-Death

of Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Polity.

Crouch, Colin. 2003. Postdemocrazia. Laterza.

Roma-Bari

[English edition 2004]. Postdemocracy. Cambridge: Polity.

De Blasio, Emiliana. 2018. Il

governo online. Nuove frontiere della politica. Rome:

Carocci.

De

Blasio,

Emiliana and Michele Sorice. 2016.

Open

Government: a Tool for Democracy? Medijske

studije 7 (14).

De Blasio, Emiliana and Michele Sorice. 2019.

Technopopulism and Direct Representation. In Multiple Populisms.

Italy as

Democracy’s Mirror, ed. Paul Blokker and Manuel Anselmi,

127-147. London

and New York: Routledge.

della

Porta,

Donatella. 2013.

Can Democracy Be Saved?

Participation,

Deliberation and Social Movements. Cambridge: Polity.

della Porta, Donatella. 2009. I

partiti politici. Bologna: Il Mulino.

della

Porta,

Donatella, Joseba Fernández, Hara Kouki, and Lorenzo Mosca. 2017. Movement

Parties

Against Austerity. Cambridge:

Polity.

della Porta, Donatella and Dieter

Rucht. 2013. Meeting Democracy. Power and

Deliberation in

Global Justice Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Deseriis, Marco. 2017. Technopopulism: The

Emergence of a Discursive Formation. tripleC: Communication,

Capitalism

& Critique 15

(2): 441-458,

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v15i2.770

Duverger, Maurice. 1951. Les parties politiques. Paris: Arman Colin.

Eagleton,

Terry.

2011. Why Marx Was Right. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press.

Forgacs, David, ed. 1999. The Antonio Gramsci Reader. Selected Writings.

1916-1935. London:

Lawrence and Wishart.

Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Digital Labour

and Karl

Marx. New York and London: Routledge.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of

History and the

Last Man. New York: Free Press.

Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2019. The Digital

Party. Political

Organisation and Online Democracy. London:

Pluto

Press.

Gerbaudo, Paolo.

2012. Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and

Contemporary Activism. London: Pluto Press.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Il materialismo storico. Roma: Editori

Riuniti.

Hall, Stuart. 1988. The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. London: Verso.

Hartle, Johan. 2017. Reification as Structural Depoliticization: The Political Ontology of

Lukács and Debord. In The Spell of Capital: Reification and

Spectacle, edited by Johan F. Hartle and Gandesha Samir, 21-36. Amsterdam:

Amsterdam University Press.

Hay, Colin. 2007. Why We Hate Politics. Cambridge: Polity.

Keane, John. 2013. Democracy and Media Decadence. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Kreiss, Daniel. 2012.Taking our Country Back: The Crafting of

Networked Politics from Howard Dean to Barack Obama. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Littler, Joe. 2017. Against Meritocracy.

Culture, Power and Myth of Mobility. London: Routledge.

Marx,

Karl. 1993.

Grundrisse. London:

Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1992. Capital. Volume II. London:

Penguin

Marx,

Karl. 1991.

Capital. Volume III. London: Penguin

Marx, Karl. 1990. Capital. Volume I.

London: Penguin

Micheletti, Michele and Andrew S. McFarland. 2016.Creative Participation:

Responsibility-Taking in the Political World. New York and

London:

Routledge.

Morlino, Leonardo and Francesco

Raniolo. 2018. Come la

crisi

economica cambia la democrazia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Moro,

Giovanni.

2013. Cittadinanza attiva e qualità della democrazia. Rome:

Carocci.

Morozov,

Evgeny.

2019. Digital Socialism? The

Calculation Debate in the Age of Big Data. New Left Review

116: 33-67.

Mouffe,

Chantal. 2005. On the

Political.

London: Routledge.

Müller, Jan-Werner. 2017. What

is Populism? London: Penguin.

Norris, Pippa, ed. 1999. Critical Citizens: Global Support for

Democratic Government.

Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Pasquali,

Francesca

and Michele Sorice, eds. 2005. Gli altri media. Milan: Vita

& Pensiero.

Pavan, Elena and Arianna

Mainardi. 2019.

At the Roots of Media Cultures.

Social Movements Producing

Knowledge about Media as Discriminatory Workspaces. Information, Communication

& Society,

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1631372

Pitkin, Hanna. 1967. The Concept of

Representation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Prospero,

Michele.

2012. Il partito politico. Rome: Carocci.

Rancière,

Jacques.

2010. Chronicles of Consensual Times. London: Continuum.

Rokkan, Stein. 1970. Citizens, Elections,

Parties. Oslo: Universitetforlaget.

Saward, Michael. 2010. The Representative Claim. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schudson, Michael. 1998. The

Good Citizen: A History of American Public Life.

New

York: Free Press.

Smythe, Dallas W. 1977. Communications:

Blindspot of Western Marxism. Canadian Journal of Political and

Social

Theory 1 (3): 1–27.

Sorice, Michele. 2014. I media e la democrazia. Rome:

Carocci.

Tormey, Simon. 2015. The end of representative politics. Cambridge: Polity.

Urbinati, Nadia. 2013. Democrazia in

diretta. Le nuove sfide alla rappresentanza. Milan: Feltrinelli.

Žižek,

Slavoj.

1999. The Ticklish Subject:

The

Absent Centre of Political Ontology. London:

Verso.

About

the Authors

Emiliana De Blasio

Emiliana De Blasio is Lecturer of Open Government and of Media Sociology at LUISS University, where she also teaches Gender Politics. She is Invited Professor of Media Sociology at Gregorian University in Rome.

Michele Sorice

Michele

Sorice is

Professor of Democratic Innovations, of Media Studies and of Political

Sociology at LUISS University, where he is also director of the Centre

for

Conflict and Participation Studies.