YouTube as Praxis? On BreadTube and the Digital Propagation of Socialist Thought

Dmitry Kuznetsov* and Milan Ismangil**

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, Hong Kong

Abstract: In this paper we discuss the rise of BreadTube and what it means for the spread and normalization of socialist ideas online. We aim to focus on four major YouTube content creators – Contrapoints, Philosophy Tube, Shaun, and Hbomberguy – to outline how they construct their videos to entertain, inform, as well as debunk both alt-right and (economically) liberal talking points, helping to prevent potential radicalization of a mostly young audience who stand at a crossroads in their ideological development. Aside from examining the content of produces by the creators, we also hope to investigate the unique configuration of their platform use, emphasizing such elements as distributions, financing, and audience interaction.

Keywords: digital, BreadTube, Reddit, digital socialism, affective media, Patreon, YouTube

1. Introduction: Enter BreadTube

In January 2019, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez dropped by an event hosted by Harry Brewis (‘Hbomberguy’), who raised money for a transgender charity by live-streaming the videogame Donkey Kong 64 for around 50 hours. In a show of international solidarity, Cortez’s act was the first big intersection of BreadTube with “real-world” political figures, the first major instance of it being propelled outside the confines of its digital origins.

BreadTube (or ‘YouTube but good’ as referred to by its adherents) is a loose association of independent online videographers and their surrounding communities that makes up a leftist response to alt-right use of digital media. The moniker Loose Association implies a lack of central organisation, of a structure that determines their relationships. Instead, a shared ideology binds them together. Including such content creators as Contrapoints, Hbomberguy, and Philosophy Tube, BreadTube stretches beyond YouTube, with a presence on various social media platforms (e.g. Reddit, Something Awful), as well as its own websites (e.g. BreadTube.tv). These digital outposts serve as video aggregators, discussion spaces, and even platforms for social mobilization.

Borrowing its name from Kropotkin’s anarchist classic The Conquest of Bread, BreadTubers and their viewers do not shy away from associations with leftist thought. BreadTube.tv claims that the goal is “to challenge the far-right content creators who have taken advantage of the profit-driven algorithms used by services like YouTube for the purpose of spreading hate” (“About · BreadTube” n.d.). They express a “wish to educate people on how their world operates, the alternative possible visions for our future, and how we organize ourselves to get there.”

Our position is that BreadTube is a form of digital praxis promoting new types of digital engagement with leftist and socialist thought. While the impact of BreadTube within the political arena is yet to be seen, the increasing popularity of its content shows a growing public awareness of the lacunas of capitalism, as is evident from reports by more traditional media outlets (e.g. Jacobson 2019; The Economist 2019).

We start this article with a reflection on the role of communication technologies in contemporary class struggles. We argue that assemblages like BreadTube present a way of applying affective media that goes beyond creation of antagonists, or pure violent jouissance associated with libertarian uses of affective media (Jutel 2017). Second, we examine how these formations aid the spread of socialist ideas. We propose that BreadTube can fulfil the educational and agitprop purposes of media, assisting in a Brechtian reconfiguration of the people (Žižek 2018): the transformation of the inert mass of the working class into a politically engaged united force.

We then discuss the applicability of socialist literature to the BreadTube phenomenon. We draw on studies of earlier leftist online communities as well as contemporary leftist theoretical scholarship, positioning BreadTube at the intersection of these two themes. In section three we engage with BreadTube itself: both the content and the virtual community (Song 2009) surrounding it. Is it possible to conceptualize BreadTube as socialist? Or is it part of the nexus of communicative capitalism, offering the feeling of change without bringing about real transformation? If – as we argue – it is the former, what makes it informative and mobilising? What does this phenomenon mean for discussions of (digital) praxis? In the final section, we reflect on the future of BreadTube, by bringing up Marcuse’s work on the Tea Party (Marcuse 2010), while considering some of BreadTube’s present limitations.

2. Helping Others Remember to Dream

BreadTube does not have a central hierarchy. It is made up of loose linkages that congregate on different social media websites, with videos serving as focal nodes that anchor discussions of ideology and praxis. Our preliminary conceptualisation of BreadTube is to see it as a catalyst, an agent preparing and hastening up conditions for change, rather than the site in which said change occurs. Discussing the prospect of radical change today, Žižek (2018, 481) argues that revolutions come to those with patience. To quote:

Revolutionaries have to wait patiently for the (usually very brief) period of time when the system openly malfunctions or collapses, seize the window of opportunity, grab the power […] so that, once the moment of confusion is over, the majority gets sober and is disappointed by the new regime, it is too late to get rid of it, and the revolutionaries have become firmly entrenched.

BreadTube serves to create the conditions

necessary for

socialism to become an acceptable reality. It helps disentangle the

meaning of

socialism from the capitalist smear campaign, re-articulates it in a

positive

light, resulting in a push towards a vision of a shared, achievable

reality. It

represents some of the “hard theoretical work” needed to break free

from the

ideological mask fixed upon the working class that makes its members

turn again

one another (blaming the immigrant, the feminist, etc.) (Žižek

2018).

BreadTube

gently

pushes its viewers to perceive the injustices thrust upon them by the

capitalist system. BreadTube’s common tactic revolves around taking a

right-wing talking point or “alternative fact” and subverting it.

Critical

analysis of such talking points as climate change denial or the Great

Replacement of Europe (i.e. the Muslim/refugee/migrant ‘invasion’)

introduces

the viewer to a gentler politics. It should be noted that unlike the

cyberlibertarian formations investigated by Jutel (2017), where antagonization of political opponents

takes centre

stage, BreadTube content tends to focus on understanding, analysis,

and

suggestion of alternatives to the talking points presented. The

discussion – be

it about the men’s rights movements (Contrapoints

2019b), Flat Earthers (Hbomberguy

2018), or Unite

The Right’s actions in Charlottesville (Shaun

2018) – stays clear of the trolling and

vulgar jouissance that

is characteristic of the alt-right (Jutel

2017). While also aiming to entertain,

this more pensive,

critical approach, while most certainly not inciting a swift socialist

uprising, may lay the necessary groundwork.

It

is

hard to classify BreadTube videos as socialist per se, and a broader

view of

leftist thought is more appropriate. In his discussion of the

continuing

relevance of Marxism, Wright (2018) raises

four

“central propositions” that remain relevant today and constitute the

basis of

our discussion:

·

Capitalism obstructs the realisation

of

conditions of human flourishing.

·

Another world is possible.

·

Capitalism’s dynamics are inherently

contradictory.

·

Emancipatory transformation requires

popular

mobilisation and struggle.

BreadTube

–

through both videos and discussions

–

directly engages with and contributes to this broad conceptualisation of

the

Marxist and socialist traditions. The first and third propositions show

the

need for BreadTube, as it helps pull back the veil of capitalism by

defamiliarizing and deconstructing the status quo. As for the second and

fourth

proposition, BreadTube can advance a popular cultural style of the

socialist

movement without explicitly naming it as such. Wright (2018)

reminds us that emancipatory transformation requires building

institutions to

embody relevant ideals, that transcending capitalism is not a manner of

rupture, but of consciously building up a foundation of socialism inside

of

capitalism. Distorting the normalcy of our capitalist world order is one of the core tasks that BreadTube undertakes.

BreadTube, despite its anarchist-inspired name, is a comprehensive host

of leftist worldviews and analyses. Some state that they are spreading

leftist

thoughts (e.g. BadMouse self-describes as creating “leftist

propaganda” (BadMouse n.d.)). Others seek to

obtain a wider audience,

rarely directly mentioning socialism. As if

in a

conscious effort to avoid the negative association socialism has

amongst those

she wishes to engage, Contrapoints (Natalie Wynn) describes her

videos as follows:

“My political aim is to counterbalance the hatred toward

progressive

movements that is so common online. Stylistically, I try to appeal to

a wide

audience and avoid merely preaching to the choir.” Orientating the

uncertain

viewer towards a type of leftist, socialist thought without

confronting them

with affective signifiers that these terms accumulated in popular

press is one

of the great strengths of this community.

Invoking the Zapatista movement’s famous notion of “One No, many Yeses”

(Wolfson 2014) BreadTube appears to embrace

heterogeneity as long as all the noses are pointed in the direction of

opposing

the capitalist status quo. This, however, leads to a problem of the

will of the

people, the theorisation of which has been a contentious issue. In

this

instance, we borrow Dean’s (2012, 114) formulation of the will of the

people as

“as a divisive political subject that produces itself through its

practices

[whose] will precedes not only its knowledge of what is willed, but

the people

itself.” As Žižek (2018, 479) argues, today

there is

no “global cognitive mapping”, no collective will. BreadTube has the

potential

to structure the previously this will by shining light upon the

frustrations

viewers might have with the capitalist system, inciting a yearning for

the

communist horizon.

Continuing this train of thought, Dyer-Witheford (2015, 10) notes that knowledge is the “main site for contesting capitalism”. For socialism to be successful, critique of ideology must become part of mainstream discourse (Fuchs and Monticelli 2018). It needs spokespersons and leaders, someone to decode academic debates and terminology, to sieve out the core message, to convey it to their audience in a clear and engaging manner. BreadTube fills an ideological void for people who may lack the means and methods to educate themselves. It is bite-sized and features well-produced video spectacles.

Fuchs (2018) notes that a Marxist theory of

communication should analyse the structure of ideology through various

channels. One must overcome “capitalism, class society, exploitation,

and

domination” (Fuchs 2018, 531). BreadTube can

have an

emancipative function of exposing the viewer to the previously unseen

flaws of

capitalism. This leads to a question of how BreadTube differs from

earlier

forms of leftist digital media.

Wolfson’s (2014) study of Indymedia can help us identify why earlier attempts at (digital) socialism failed. He argues that Indymedia organisers did not set clear goals, only asking themselves “What do we want to achieve?”. Without a strong aspiration it was difficult to organise and invoke societal change. This, in combination with a lack of clear leadership or organisational forms, led to the diminishing effectiveness of this media project. While BreadTube exhibits similar issues, the crucial differentiating factor is that this community is centred around individual content creators. While said creators have not yet exhibited interest in changing their platform from one of words into one of actions, they are engaged in a style of informational warfare with the modern right.

Dean

(2012),

discussing Occupy Wall Street, states that for communism to flourish

we

must not simply be together, but rather “stick together”, turning our

collective

desire into actual change. A desire that must be channelled into

action by

leaders (Žižek 2018) who can formulate

strategies and

educate. This

desire

can be misguided – as we in the past few years have seen this desire

being harnessed by extremists to cast the blame upon the refugee, the

immigrant, the other. Crucially, we must remember that “strategies

don’t just happen” (Wright

2018, 499).

On social media, activism-related discussions are a frequent sight,

urging people to go beyond the videos: “Watching YouTube videos never

led me to

praxis – reading theory did” (BobartTheCreator2

2019). BreadTube can thus be seen as a gateway to socialist

thinking. It

utilises the information infrastructure of capitalism to present the

masses

with visions and dreams of a better, fairer world: something that left

has

failed to accomplish up to this point (Dear 2012). Dean argues that we

have

unlearned how to dream of a better future, and it is up to communists

to show

why socialism is “the best alternative” to capitalism” (83). Some

BreadTubers

directly state that their reason

for making

videos is to counteract the growing influence of the alt-right on the

internet (Contrapoints

2019a; Hawking 2019).

Having looked at a range of discussions and interpretations of Marxist

thinking, it appears that BreadTube can perform a variety of essential

functions, including promoting socialist ideals, educating the

population, and

sparking the dream of socialist transcendence. Moreover, it can serve

to

connect the work of theoreticians with practical mobilisation,

preparing the

discontented population by promoting the central propositions outlined

by

Wright (2018).

All this sounds good, but one wonders whether BreadTube has the capacity to formulate a collective will capable of affecting change. Its decentralised nature, the style of content produced, the channels of its distribution and the format of its discussions can be seen as strengths or as weaknesses. We must more thoroughly investigate these constitutive elements.

3. Analysing BreadTube

YouTube is the root, the platform where videos get posted and disseminated by content creators. These videos are discussed in the comment section of the platform, but most of the discussion takes place on social media platforms such as Reddit or Internet forums like Something Awful. Reddit is a website that hosts a multitude of subreddits, each a community that regulates its content through voluntary moderation, with the admins proper only interfering in extreme cases (e.g. child pornography).

A viewer might become curious and follow the links provided in the video description or the comments. This would lead them towards the major BreadTube discussion spaces where, in an ideal case, they could be guided towards a gentler politics. Simply put, this is a two-layered “hijacking.” The first layer involves use of search algorithms by BreadTubers to disseminate their videos. The second layer – a kind of affective hijacking – revolves around using a variety of theatrical and didactical styles to convey leftist thought. The system is well summarised by Roose:

The core of BreadTube’s strategy is a kind of algorithmic hijacking. By talking about many of the same topics that far-right creators do – and, in some cases, by responding directly to their videos – left-wing YouTubers are able to get their videos recommended to the same audience (Roose 2019)

3.1. BreadTube’s Logistics and Funding

The

platform

dependent nature of BreadTube requires us to consider its position at

the intersection of communicative capitalism and affective media.

Does it have emancipative potential or is it a form of

affective media labour, with capital “contradicting the productivity

of

biopolitical labour and obstructing the creation of value” (Hardt

and

Negri, 2009, 144)?

Through

affective media we are made to think of ourselves as parts of a bigger

narrative, apparently

fighting

capitalism online, while in fact contributing to its continued

existence.

Most major BreadTubers use YouTube to spread their ideas. Some of them acknowledge Google’s role in the propagation of hate but are in the end reliant on it. As a small sign of resistance, some BreadTubers use Patreon (a crowdfunding platform) to make a living, with some opting out of monetising their videos (i.e. turning off advertising). Patreon serves to democratise socialist knowledge. BreadTubers’ videos are free to watch and discuss online. Those able and willing to fund the production are invited to make direct contributions.

Democratisation of knowledge is explicitly mentioned by Philosophy Tube, who after austerity in the UK education system “decided to give away [his] MA in Philosophy free to people who don't have the opportunities for learning [he has] had” (Philosophy Tube n.d.). He wants to “get people in a position where they can take cutting edge academia and apply it to the real world” (n.d.). The image of leaving the ivory tower to is a common theme within the BreadTube community.

To sum up, the work of BreadTubers is a reconfiguration of socialist promoted via capitalist information structures with the goal undermining them. These videos serve as discussion nexuses, forming communities of practice. Ideally, the more well-versed can guide those who, after having seen a video, are looking for more answers. An example of this is shown below:

Figure 1: Revolution UK subreddit announcement

These videos appear to have a ripple effect. The Revolution UK community features many links to protests, mixed with questions from people frustrated with the status quo. For example, one commenter says they are “[t]ired of the left being purely reactionary but feel powerless to actually help in any capacity” (Azulmono55 2019).

Earlier we presented BreadTube as a catalyst or gateway towards socialist thought. As shown, the various pathways that lead from BreadTube videos can put a viewer on the road towards discussions, consideration, and acceptance of leftist thought.

3.2. The Content

One of the difficulties in defining BreadTube is its inclusiveness. There is no arbiter, nor any clear notion of what a ‘BreadTube video’ is. Rather, it is through consensus that work gets incorporated into the canon. This happens through discussions on forums, voting on Reddit or simple agreement between users. In this article we focus on the four largest YouTube channels whose videos are frequently discussed in the BreadTube communities. These are Shaun, Hbomberguy, Contrapoints, and Philosophy Tube. Their content can be generalised into two categories: the response video and the explanatory video.

In the first type, a (right-wing) talking point is explained, analysed, and debunked. For example, Hbomberguy in the ‘A Measured Response’ series tackles climate change denial propagated by popular right wing YouTube channels. Similarly, Shaun in ‘A Response To...’ directly engages with other YouTube channels, discussing topics such as why ‘European History Is Not White History’, ‘Feminism, Why You Need It’, or ‘What Is White Supremacy’. Shaun also has a video series on how ‘PragerU Lies to You’. PragerU is a right-wing propaganda outlet, “one of the most effective conversion tools for young conservatives” (Nguyen 2018). These response videos use popular (right-wing) talking points to anchor discussions surrounding issues such as feminism, right-wing outrage, socialist alternatives, the manufacturing of ‘cultural Marxism’, and so on.

The second category – the explanatory video – has a more general aim: rather than focusing on a particular point, these videos introduce and analyse a larger theme. The work of Contrapoints and Philosophy Tube exemplify this approach. The former covers topics such as ‘Incels’, ‘The West’, ‘What’s Wrong With Capitalism’, ‘The Apocalypse’, and ‘Beauty’, and the latter delves into the subjects of ‘Reform or Revolution’, ‘Witchcraft, Gender, & Marxism’, and ‘Elon Musk’.

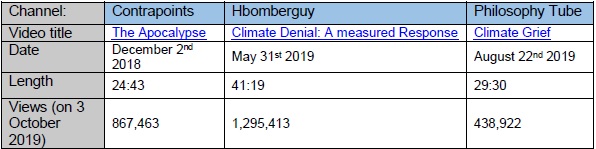

We have selected three recent videos about the climate disaster to serve as examples (Table 1). As Shaun does not have a video on this topic, we did not include him.

Table 1: Basic YouTube video information

While this is but a small sample of the BreadTube universe, we believe these videos are good demonstrations of how leftist (socialist, progressive) thought is embedded in video content, how it is relayed to the viewer.

3.2.1.Philosophy Tube: Climate Grief

In Climate Grief, Philosophy Tube discusses the climate disaster in its totality. In his productions, he speaks directly to the viewer in the guise of different personas. In this case, the central character is a kind of futuristic priest delivering a eulogy at the “funeral for planet earth.” Another recurring character is the “travelling salesman,” a caricature of a (neo)liberal who proclaims himself to be moral, preaching ‘responsibility’ and ‘rational debate’ while seeking faults in others. Central to the video is the argument that climate change is not one problem, but a composite of many problems. Borrowing a term from philosopher Timothy Murton, he refers to the climate disaster a hyper object.

Philosophy Tube makes frequent use of a variety of literature to support his arguments. Another example is the use of Terry Eagleton’s Why Marx Was Right (Eagleton 2011) to argue that the acknowledgement of the world as tragic fuels fascism, “persuasive to so many liberals because it acknowledges that many things just suck.”

Philosophy Tube criticises both right wing climate change denial and left-wing techno fetishists that believe in technological solutions (citing Bastani’s book Fully Automated Luxury Communism (2019)), arguing that there is more than one way to deny climate change. He asserts that the tragedy of the current situation is our sense of powerless, the belief that those at fault might never reap what they sow. He does offer hope, however, arguing that smaller and within-reach acts of unionisation, empathic politics, listening to indigenous people and their philosophies are all part of understanding and dealing with the climate disaster. He concludes by stating that:

[R]ather than not thinking about it, or hoping for a perfect technological solution seriously considering the world might end with climate change might be a chance to ask: what were the good bits? Apocalypse doesn’t actually mean the end of the world, it’s a Greek word that means the revealing of knowledge.

Philosophy Tube poses questions and dilemmas while supplying answers and workable solutions: listen to indigenous philosophies, recognise that you have more allies than you think, that we are not alone in the our individual struggles but are part of a greater whole (a covert case of class analysis if there ever was one). Climate change is a host of issues rather than one isolated struggle. We need to think about how we want the world to look after the apocalypse.

3.2.2.Contrapoints: The Apocalypse

Contrapoints’ The Apocalypse – like many of her other works – employs a discursive-dialectical technique. The video features a scientist that tries to convince a decadent denier (lying in a bath) of two things: that climate change is real, and that the world needs to be saved. The video involves the scientist explaining things to the denier (or the audience) after which they shortly discuss the content, with the denier occasionally interrupting the video. The explanatory parts are factual, discussing the consequences of climate change, as well as the lobbying efforts to deny, delegitimise and supress climate change policies. The strength and impact of Contrapoints’ content lies in the discussion elements.

The conservative climate change denier begins on the premise that the scientist seeks only to “shove the liberal agenda down [their] throat”. But the latter retorts through engagement with the denier’s own rhetoric, asking if she wants more refugees (“no!”), then arguing that climate change policies need to be implemented to avoid that (“no!”), or otherwise more refuges will come (“no!”). Contrapoints does her best to pre-empt arguments from those on the opposite end of the political spectrum, and this allows her productions to go beyond antagonism by showing an understanding of the other side.

Contrapoints provides guidance, emphasising practical individual and group involvement: we need to push for rapid political change, go on strikes, vote, demand action. She states that capitalism cannot provide a solution to climate change due to its propensity for short term thinking, which is incompatible with the long-term orientation of climate change. The video ends humorously with the acknowledgment that the conservative needs an antagonist, which echoes earlier findings on cyber-libertarians and affective media (Jutel 2017): “how am I supposed to care about rising sea levels? There are Muslims and Mexicans – there could be Muslim Mexicans for all I know”. Ending on a joke, the scientist conjures up an opposition figure for the denier. The Dark Mother – the Sea – who threatens to consume the planet.

3.2.3.Hbomberguy: Climate Denial

In contrast to the other two channels, Hbomberguy plays himself talking straight to the camera, occasionally cutting to relevant footage or comedic sketches. He admits he is not an expert – he was originally a videogame YouTuber – and relies less on academic writing, speaking more from his own experiences. Unlike the previous examples, he directly attacks some talking points explicitly highlighting their wrongness rather than leaving the moment of realisation with the viewer. The video employs a personable approach with Hbomberguy wondering how climate change deniers are able to persist despite the obvious flaw in their arguments, debunked with a few seconds googling. The video first discusses why the “science” of climate change denial is based on lies. It then outlines how denialism works by pointing out stakeholders (e.g. oil companies) with vested interests.

Discussing popular right-wing figures such as Stephen Crowder and Patrick Moore, Hbomberguy explains to the viewer how they manipulate those on the fence (the conservative audience), how they make the audience feel good about themselves by asserting their viewpoint as the right one. Hbomberguy notes: “The product [Stephen Crowder] is selling is ideology.” The main point of the video is not about climate change but the mechanisms of this ideology, how its rhetoric is sold to the people, how a veil of ignorance and denial gets woven and placed over their minds. Hbomberguy reveals the inherent contradictions of right-wing discourse that claims to stand for reason and facts, to be pro-science. Joking that “climate change isn’t your fault, it’s the Koch’s brothers’ fault,” he argues that the most effective strategy is to agitate for political change. The video ends in a hopeful manner, stating that if even someone like him can realise that these people are just being paid to make him feel good, then perhaps all of us can pierce the veil.

3.2.4.Synthesis

The

videos

discussed lay bare the inherent contradictions of the right-wing

stereotype: logical, science-adhering sceptics who prefer reason to

feelings. What sets these

channels apart from the

more radical BreadTube adherents is their neutral appearance, which

allows them

to attract a wider viewership and to attain relevance beyond a leftist

or

socialist echo chamber.

Often there are no winners in these videos. Rather, they assert that deciding on the truth of the matter is left to the viewers. Philosophy Tube, Contrapoints, and Hbomberguy tell their audiences to look at the sources themselves, to witness the debate at hand, to establish their own viewpoint. This stands in contrast to the contentious politics of the likes of Ben Shapiro or Jordan Peterson, who popularised themselves on the wave of the ongoing populist right-wing resurgence. They rely on the creation of antagonists as acknowledged in Contrapoints’ video, positioning their ideological opponents as sources of all that is wrong with the world.

On BreadTube, antagonization does not take centre stage. There is a level of honest engagement with opposing arguments. Unlike cyberlibertarian forms of affective media that prioritise jouissance (Jutel 2014) over other themes, there are no real gotcha moments, no one-liners. The intent is not to create enemies (a constructed other) but to examine, deconstruct and critique the points brought up. This might be due to the independence of these creators and the democratisation of their videos through voluntary donations. Unlike many of their counterparts, BreadTube content creators by and large do not have a product or point of view to sell. They are therefore freer to discuss any topic in any way they wish[1].

Channels such as Philosophy Tube or Hbomberguy take a more liberal approach with their format, structuring their work like mini-documentaries or television series. But what is consistent across these content creators’ videos is production value. Their videos have been professionalised as the popularity (and income) of the channels increases. We view this as a positive evolution. Videos like these serve to introduce a new generation to ideas and viewpoints which they otherwise may not have encountered.

3.3. The Community

The largest discussion site for BreadTube is Reddit, a social media platform that is infamous for being extremely laisse faire in its content moderation. Reddit hosts a number of fascist, extreme right, nationalist forums that spread hate and discontent on the Internet. Analysing the website, Massanari (2017) argues that its design implicitly promotes a techno-culture that encourages toxic behaviour.

There is friction between acknowledgement of these platforms (e.g. YouTube, Reddit) as tools of (capitalist) oppression, and relying on them for the means and methods to spread and discuss leftist ideas. This leads to some interesting parallels with the real world. The subreddit for the popular leftist/anarchist podcast ChapoTrapHouse recently got “quarantined” due to repeated calls for violence. This means that it does not receive any advertising and is delisted from the main site. This development was received as good news by many, considered to be a form of “digital squatting” (larrikin99 2019).

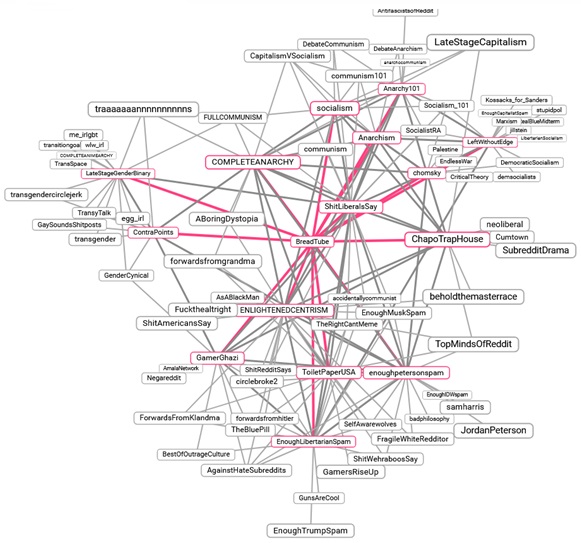

A socialist worldview ties together networks such as ChapoTrapHouse and BreadTube. Due to their sparseness, there are difficulties in making decisions across networks, or even within one. Organisational power is something that we should not expect from BreadTube. Rather, BreadTube is more a gateway to further activism, a tool for the untangling of our ideological shackles. It is a catalyst that speeds up the development of favourable conditions under which things can progress and change. Figure 2 is a network graph that show in which other communities users from the BreadTube subreddit are active. We used data from August until September 2018.

We

can

see a leftist Reddit network with sub-communities such as Anarchism,

Communism, and Anti-Capitalism. There are links to communities

dedicated to

educating the people (Socialism101, debatesocialism,

LateStageCapitalism) but

also subreddits focused on organising action.

Figure 2: Networks of commenters who post in BreadTube and other Subreddit Communities

Below is an example from a post on LateStageCapitalism discussing climate change activism.

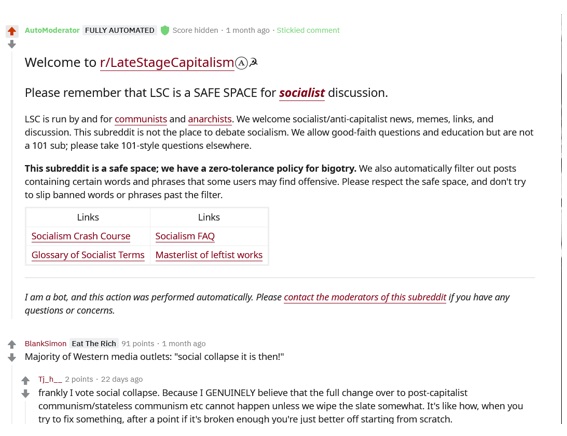

Figure 3: Climate change activism on the LateStageCapitalism subreddit

Figure 4: Introduction text on every comment thread on the LateStageCapitalism subreddit

Several of these communities have a strong didactive element where people ask questions and get answers from those more versed in leftist thought. A common sight on many leftist subreddits are recommended book lists, some even hosting recurring book clubs. There is a grassroots element with users educating themselves, often drawing directly from the classical works of socialism.

BreadTube is a general catch-all leftist subreddit meaning that its content is not that radical. It has an pedagogical function, guiding users to ways to educate themselves through readings, videos, and other types of media.

Figure 4 shows that BreadTube is not an isolated instance but a central node of the left-leaning Reddit sphere. It belongs to a constellation of leftist communities, constituting a starting point of a journey towards leftist thought, towards deconstruction of the (ideological) bias against socialism that has accumulated due to decades of propaganda, with Trump and Johnson being the most recent and vocal examples (Cammaerts et al. 2016) of socialism’s vilification. On 24 September 2019, Donald Trump vowed in his United Nations speech to “never let America become a socialist or communist country” (Schwartz 2019). On 2 October 2019, UK Prime Minister Johnson called for “raising the productivity of the whole of the UK, not with socialism [...] but by creating the economic platform for dynamic free-market capitalism” (Mason 2019). An important question remains: How can socialism best be understood today?

4. Discussion: Everyday Critical Theory

Grassroots localised socialist revival is growing

on

certain Internet spaces. While many caveats exist, there is hope for

social

change and public mobilisation. BreadTube signifies a return to a

classic,

democratised socialist mass education programme. However, there is a

risk of

BreadTube becoming subsumed under neoliberalism and individualism if

socialism

is seen and practiced as fashion rather than a political and social

need.

There is also the threat of techno-fetishism, that BreadTube might fuel the assumption that open source software and knowledge constitutes socialist praxis or is socialism. Jutel (2017) points out the dangers of such techno-fetishism, that it can lead us to believe we are acting politically by clicking, making us feel good and righteous while playing into the hands of a capitalist society. The collective potential of this community is yet to be revealed, as it has mainly operated within the boundaries of the platform(s). A further question is whether there is any potential for transcending the common forms of political participation and change, as the democratic exercise of voting is a questionable method of pushing for real change. However, faith in the democratic process remains, exemplified by calls for people to vote Trump out of the office (Contrapoints 2018).

Use of social media for political education and mobilisation occurs not only in leftist movements, but also among the alt-right who rely on affective media and video production to radicalise youths. This behaviour has had a substantial yet sombre impact on the real world, exemplified by the Christchurch shooting and the Charlottesville massacre. These and other examples show the negative potential that is inherent to social platforms and media content-based mobilisation.

Another concern is whether and how BreadTube can engage those on the opposite side of political debates. Recent media coverage (see Fleishman 2019) has highlighted that BreadTube can de-radicalise the radical right (Fleishman 2019). Commenting on her videos covering alt-right talking points, Contrapoints said: “Deradicalizing is part of my work, maybe even the most important thing I've done” (Contrapoints 2019a).

BreadTube does not exist in isolation. It is part of a larger movement against right wing and populist thought that have dominated the media landscape over the past few years. In 2010 Peter Marcuse wrote an article analysing the Tea Part movement. Why did it suddenly explode in popularity and what can we do to counteract it? Written before the rise of the alt-right, Marcuse conceptualises the Tea Party as “repression from below, not from above” (2010, 356). He argues that there is a need for critical theory in everyday life – a critical theory from below – to steer individuals’ frustrations with the system towards proper causes and solutions. His categorisation of resistance as individual or collective, comprehensive or partial, serves to emphasise the need for BreadTube, as it allows for bottom up critical engagement to be embedded in everyday life. The “extreme displacement,” as Marcuse calls it, felt by many due to the havocs of capitalism can be channelled towards a progressive form of resistance rather than being co-opted by the alt-right.

It remains to be seen in what ways the BreadTube content creators are able (or willing) to transform themselves into more overt political actors. It is unclear if this is something we should ask of them, as their role might be to act as guides, starting points for education and mobilisation.

However, what remains certain is that like Lenin standing on the train and speaking to workers more than a hundred years ago, BreadTube is a socialist movement. Technological progress has given us tools that allow for the advancement of socialism. BreadTube subverts techno-capitalism and hijacks YouTube’s algorithms in order to spread leftist thought. Rather than being stuck on rails, Lenin’s train now takes the form of smartphones and online videos, allowing emancipatory politics to integrate seamlessly into everyday life.

References

About. BreadTube. n.d. Breadtube.Tv. Accessed October 10, 2019. https://breadtube.tv/about/

Azulmono55.

2019.

Realistically, How Can a Generic Person Outside a Big City Start to

Make

a Difference? Reddit [blog]. September 8, 2019. Accessed 4

January 2020.

https://www.reddit.com/r/revolutionUK/comments/d1fxqf/realistically_how_can_a_generic_person_outside_a/

BadMouse.

n.d.

BadMouse Is Creating Leftist Propaganda. Patreon. Accessed October

7,

2019. https://www.patreon.com/Badmouse

Bastani,

Aaron.

2019. Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto.

London: New

York: Verso.

BobartTheCreator2. 2019. You Shouldn’t Get All Your Theory from YouTube

Videos. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/BreadTube/comments/cfp6xy/you_shouldnt_get_all_your_theory_from_youtube/

Cammaerts, Bart, Brooks DeCillia, João Magalhães, and César

Jimenez-Martínez. 2016. Journalistic Representations of Jeremy

Corbyn in the

British Press: From ‘Watchdog’ to ‘Attackdog. London: The London

School of

Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/research/research-projects/representations-of-jeremy-corbyn.aspx

Contrapoints. 2019a. Natalie Wynn on Twitter: ‘Hey Guys Here’s My

Thoughts about Press Coverage of Me Primarily Focusing on

“Deradicalizing the

Alt-Right.” Deradicalizing Is Part of My Work, Maybe Even the Most

Important

Thing I’ve Done. I’m Grateful for the Recognition. But I Don’t Want

to Be

Pigeonholed Either. Short Thread’ / Twitter.” Twitter. June

14, 2019. https://twitter.com/contrapoints/status/1139427430572146688

Contrapoints. 2019b. Men | ContraPoints. Accessed January 6,

2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1xxcKCGljY

Contrapoints. 2018. The Apocalypse | Contrapoints. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6GodWn4XMM&t=2s

Eagleton,

Terry.

2011. Why Marx Was Right. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fleishman,

Jeffrey.

2019. Transgender YouTube Star ContraPoints Tries to Change

Alt-Right

Minds. Los Angeles Times, June 12. Accessed 6 January, 2020.

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-st-transgender-youtuber-contrapoints-cultural-divide-20190612-story.html

Fuchs,

Christian.

2018. Karl Marx & Communication @ 200: Towards a Marxian Theory

of Communication. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism &

Critique. Open

Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 16

(2): 518-34.

https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i2.987

Fuchs, Christian, and Lara Monticelli. 2018. Repeating Marx:

Introduction to the Special Issue "Karl Marx @ 200: Debating

Capitalism

& Perspectives for the Future of Radical Theory". tripleC:

Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for

a Global

Sustainable Information Society 16 (2): 406-414. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1037

Hawking,

Tom.

2019. How a 57-Hour Donkey Kong Game Struck a Blow against Online

Toxicity. The Guardian, 22 January, Games section. Accessed

January 4,

2020. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2019/jan/22/how-a-57-hour-donkey-kong-twitch-stream-struck-a-blow-against-gamergate

Hbomberguy. 2018. Flat Earth: A Measured Response. Accessed

January 4, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2gFsOoKAHZg

Jacobson,

Gavin.

2019. The Rise of Millennial Socialism. New Statesman America,

June 5. Accessed January 6, 2020. https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2019/06/aaron-bastani-fully-automated-luxury-communism-bhaskar-sunkara-manifesto-milennial-socialism-review

Jutel,

Olivier.

2017. Affective Media, Cyberlibertarianism and the New Zealand

Internet Party. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism &

Critique. Open

Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 15

(1):

337-354. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v15i1.781

larrikin99.

2019.

Chill Folks, Being Quarantined Is Good. Message Board. Reddit.

Accessed January 6, 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/ChapoTrapHouse/comments/cmyioc/chill_folks_being_quarantined_is_good/

Marcuse,

Peter.

2010. The Need for Critical Theory in Everyday Life: Why the Tea

Parties

Have Popular Support. City 14 (4): 355-369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2010.496229

Mason,

Rowena.

2019. Boris Johnson’s Speech to the Tory Party Conference –

Annotated. The

Guardian, October 2, 2019. Accessed 6 January, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/ng-interactive/2019/oct/02/boris-johnsons-speech-to-the-tory-party-conference-annotated

Philosophy Tube. n.d. Philosophy Tube Is Creating Philosophy Videos.

Patreon. Accessed October 8, 2019. Accessed 4 January, 2020. https://www.patreon.com/PhilosophyTube

Schwartz,

Ian.

2019. Trump: “America Will Never Be A Socialist Country”; “We Were

Born

Free And We Will Stay Free”. Real

Clear

Politics. February 5. Accessed January 6, 2020. https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2019/02/05/trump_america_will_never_be_a_socialist_country_we_were_born_free_and_we_shall_stay_free.html

Shaun.

2018.

Charlottesville: The True Alt-Right. Accessed January 6,

2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcoYKuoiUrY

The Economist. 2019. Millennial Socialism - The

Resurgent

Left, February 14. Leaders Section. Accessed January 6, 2020. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/02/14/millennial-socialism

Wright,

Erik

Olin. 2018. The Continuing Relevance of the Marxist Tradition for

Transcending Capitalism 11. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i2.968

Žižek,

Slavoj.

2018. The Prospects of Radical Change Today. tripleC:

Communication,

Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global

Sustainable

Information Society 16 (2): 476-489. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1023

About the Authors

Dmitry Kuznetsov

Dmitry Kuznetsov holds degrees in Media and Communication (BA, Sussex University) and Global Communication (MA, CUHK). He is interested in video games, memes, internet governance and the political economy of online content creation and sharing platforms.

Milan Ismangil

Milan

Ismangil holds degrees in musicology

(University of Amsterdam) and Asian studies (University of Leiden). He

writes

about representation in popular culture, internet culture, Esports,

and change.

For more visit https://notjustaboutculture.com/