Brazilian Blogosfera Progressista:

Digital Vanguards in Dark Times

Eleonora de Magalhães Carvalho*, Afonso de Albuquerque** and Marcelo Alves

dos Santos Jr***

*Pinheiro Guimarães College, Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil, eleonoramaga@gmail.com

, https://eleonoramagalhaes.wixsite.com/website

**Fluminense Federal University, Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil, afonsoalbuquerque@id.uff.br

***Fluminense Federal University, Brazil, marcelo_alves@id.uff.br, www.marceloalves.org

Abstract: This article explores the Brazilian Blogosfera Progressista (Progressive Blogosphere, hereafter BP), a leftist political communication initiative aiming to conciliate an institutionalized model of organization with a networked model of action. Despite the disparity of resources existing between them, BP proved able to counter effectively the mainstream media’s political framings, thanks to wise networking strategies, which explored the communicative opportunities offered by social media. The Centro de Estudos de Mídia Alternativa Barão de Itararé – Barão de Itararé Alternative Media Studies Center – is an essential piece in this schema, as it works as a coordinating agency for BP members and trains new participants. Our article intends to discuss this and other characteristics of BP as a group, and the challenges it faces at the present, after the rise of Jair Bolsonaro to Brazil’s presidency.

Keywords: Blogosfera Progressista, counter-hegemonic media, activism, Brazil, Vanguard, Networked Organization

1.

Introduction

In

June

2013, massive demonstrations – known as the Jornadas de Junho

(June

Journeys) – took place in several cities in Brazil. The immediate

factor

triggering protests in the city of São Paulo was the rise of the bus

fares,

from 3,00 to 3,20 reais. Other demonstrations followed and,

soon, they

“were not only about the 20 centavos”; they also demanded better

social

services (as health and education), complained against the realization

of the

FIFA World Cup in 2014, and the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games, in 2016,

and

denounced government corruption, among numerous other topics. They

were hailed

as a vibrant example of a new model of politics, one allowing the

crowds to

demonstrate (and even impose) their will to the political elites.

Scholars soon

identified parallels between these demonstrations and others occurring

around

the world, as the Occupy movement in the United States and Europe, the

Indignados movement in Spain, the Arab Spring, among many others (Castells

2012). These movements were presented as a

radically new type of political mobilization, capable of uniting

different

political agendas, a model that Bennett and Segerberg (2013)

named “connective action”, which was

made possible by the emergence of social media.

In retrospect, it seems clear that the Jornadas

de

Junho backfired. When the demonstrations began, the Brazilian

presidency

was already in the hands of PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or

Workers’

Party) for ten years. During this period, consistent social policies

led

millions of people to ascent from poverty to a middle-class status,

numerous

public universities were created, and affirmative policies allowed for

the

first time a massive number of non-white people to have access to

them.

Additionally, the economy looked solid, and Brazil enjoyed a

considerable

prestige in the international arena. President Luis Inácio Lula da

Silva ended

his two-terms period (2003-2006 and 2007-2010) with a record high

popularity,

and just before Jornadas de Junho, his successor Dilma

Rousseff was very

popular too (Ballestrin 2019; Singer

2019). Ironically, most leaders of the first

demonstration were members of PT, aiming to push the party more to the

left.

However, as they disdained the very idea of a political vanguard, they

were

incapable to coordinate actions in order to obtain practical results

from the

protests. Even worse, right-wing militants infiltrated the

manifestations and,

little by little, proved able to hijack their agenda, by changing the

focus to

corruption, and then to PT’s corruption.

Additional manifestations occurred in 2014 –

this time against the FIFA World Cup – and contributed to weaken PT

and

president Rousseff, who, despite this, managed to be re-elected.

Protests

asking Rousseff to be impeached began just after she was sworn in, in

January

2015 – this time carried out by right wing groups and supported by the

mainstream media, with basis on the allegation that PT was a “criminal

organization”. Under a strong attack both from the Judiciary – the Lava

Jato

Operation, led by Judge Sergio Moro, turned from a general

anti-corruption

crusade into an anti-PT movement – and the mainstream press, Rousseff

was

impeached in 2016, in a parliamentary coup. In 2018, Lula was arrested

after a

Kafkaesque judicial process, and prevented in disputing the

presidential

elections. Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right politician, won the elections

and invited

Moro to be his Minister of Justice (Feres

Junior

and Gagliardi 2019). In a short term, neoliberal policies

reverted

the previous social conquests, political repression peaked, the

universities

went under attack. Interestingly, the bus fare in São Paulo is now

4,30 reais.

The disdain regarding the importance of the

political vanguards proved to be a core fragility for the Jornadas

de Junho

movement. Yet, despite the massive attention it received, this is not

the only

existing model that explores the potentialities of digital media for

political

mobilization. This article explores one of these alternatives: The

Brazilian Blogosfera

Progressista (Progressive Blogosphere, hereafter BP) a leftist

political

communication initiative aiming to conciliate an institutionalised

model of

organisation with a networked model of action. Despite the disparity

of

resources existing between them, BP proved able to counter effectively

the

mainstream media’s political framings, thanks to wise networking

strategies,

which explored the communicative opportunities offered by social

media. The Centro

de Estudos de Mídia Alternativa Barão de Itararé – Barão de

Itararé

Alternative Media Studies Center – is an essential piece in this

schema, as it

works as a coordinating agency for BP members and trains new

participants.

Contrary to that suggested by Bennett, Segerberg and Castells, we

contend that

there is still room for collective models of activism and old

principles

characteristic from socialist activism – as the vanguard model of

organization

– remain valid nowadays, in a growingly digital environment.

The article is organized as follows. It

starts with the origins of BP in light of two historical antecedents:

1) the

influential role that communist professionals exerted in the process

of

modernization of the Brazilian journalism, in the 1950-70s; 2) the

tradition of

independent journalism, which developed in Brazil during the military

dictatorship era, in the 1960-70s. The third section discusses the

organisational

characteristics of BP. It proposes a typology of its members,

describes its

networking structure and the vanguard role that Barão de Itararé

Center

performs on it. The fourth section focuses on BP modus operandi and

its impact

as a counter-hegemonic media. The fifth and sixth sections discuss,

respectively,

the challenges faced by BP after the 2016 coup, and the surprising

opportunities that the chaotic Bolsonaro government present to the

rebuilding

of the Brazilian left. The final section looks for general lessons

from the BP.

It is argued that the logic of collective action remains as necessary

as ever

for social movements, and that models of organization originated from

socialism

– as the organizing role of political vanguards – are still necessary

in order

to allow them to establish and pursue coherent strategies and courses

of

action.

2. Historical Context

The origins of BP in Brazil can be

traced to

2006, when political activists and journalists joined efforts in

search of a

counter-hegemonic alternative to the conservative mainstream media,

one of the

most concentrated in the world (Moreira 2016).

After

the return of democracy, in 1985, Brazilian mainstream media claimed

to exert a

quasi-official branch of the government, whose attributions included

to act as

a moderating power with respect to the three official branches of

government,

intervening in political issues “for the sake of democracy” (Albuquerque

2005; Guimarães

and Amaral 1988). Concretely, this implied in systematically

taking sides

against the political left in general and PT in particular (Azevedo

2017; Feres

Junior and Gagliardi 2019)), as well as, championing neoliberal

policies as

corresponding to the “national interest”.

After Lula was sworn in as Brazil’s

president, in 2003, the mainstream media lost much of their ability to

influence

the government’s political agenda, but still remained very powerful.

In the

following years, they used this power as a means to destabilize Lula

and PT, by

associating them to negative values as populism, corruption, and

authoritarianism

(Albuquerque 2019), but this was not

enough to

avoid Lula’s reelection in 2006, and from making Dilma Rousseff his

successor

in 2010 – she was also reelected in 2014. As this happened, they

engaged in a

campaign aiming to defeat PT by any means (Damgaard

2018; Feres Junior and

Sassara 2018).

This finally worked, as President Rousseff was deposed in 2016, and

Lula was

put in jail in 2018 – in both cases after very controversial political

and

judicial processes.

It was against this backdrop that

BP emerged

as a counter-hegemonic medium. Still, other factors must be taken in

account to

understand BP’s development in Brazil. A first aspect that influenced

the

progressive blogosphere in Brazil refers to particular characteristics

of the

development of Brazilian journalism and how it impacted on the

journalists’

professional culture. Two elements may be emphasized here: 1) the

considerable

influence that communists exerted in the Brazilian journalistic

culture, in the

decades following the end of World War II; 2) the rise of an

independent

journalism movement in the 1960-70s.

In the 1950-70s, there were many communists in Brazilian newspapers – even in conservative ones – some of them in editorial positions. The owners of these newspapers were aware of the presence of communists, but they did not matter – O Globo’s owner, Roberto Marinho used to refer to them as “my communists” (Albuquerque and Roxo da Silva 2009). This happened for different reasons. First, most Brazilian communists had a middle-class background, rather than a working-class one, and communism had a considerable appeal for a large part of Brazilian intelligentsia. This made them particularly attractive in a time when journalism experienced a modernisation process and needed a skilled workforce. Additionally, the Leninist views about the importance of the newspapers as an instrument for political organization contributed to make journalism more attractive for Brazilian communists (Serra 2007). Yet, the presence of communists in the newsrooms has come with a price: They were expected to not engage in subversive activities and be acquiescent to the newspapers’ editorial lines. In fact, the newspapers’ owners considered them as being a particularly disciplined group of journalists. In exchange, they enjoyed some autonomy in everyday routines in the newsroom, which allowed them to hire fellow communists. Paradoxically, the Communist Party’s structure worked as a factor reinforcing the discipline in the newsrooms. This non-orthodox pact made sense because Brazilian communists had a reformist, rather than revolutionary approach to politics, and were disposed to make alliances with sectors of the bourgeoisie (Albuquerque and Roxo da Silva 2009).

This arrangement endured until the

end of

the 1970s. At that time, in a context of growing competition,

newspapers looked

for a more professional management system, in which the communists

were not

necessary anymore (Albuquerque

and Roxo da

Silva 2009). Added to this, the Communist Party was not as

influential as

before, as the Workers’ Party (PT) emerged as a political force

disputing its

hegemony in the Brazilian left. Different from the communists, petista

journalists viewed the newspapers’ owners as adversaries, as they

imposed an

“economic censorship” that prevented them to make “real journalism” (Smith 1997). The journalists’ unions became

particularly

active in voicing an anti-capitalistic view of journalism, by

demanding social

control of the news (Roxo 2013).

A parallel development refers to

the rise of

a model of independent journalism in Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s (Kucinski 1991). At that time, Brazil

experienced a

brutal military dictatorship, which systematically repressed the

freedom of

expression and brutalised journalists (Kushnir

2004;

Smith 1997). However, this did not prevent

the

mainstream media outlets to unambiguously support and being generously

rewarded

for this (Guimarães and Amaral 1988;

Kushnir 2004). In such circumstances, many

journalists

came to believe that the only possible manner to exert their

profession was

outside the mainstream media, as independent journalists. Numerous

independent

outlets were created, but most of them were short-lived, as they fell

victim to

political repression and economic difficulties (Kucinski

1991). However, the independent journalism ideal remained

influential in

Brazilian journalism’s culture, and together with the anti-capitalism

agenda,

it served as an inspiring source to the BP.

A second factor that influenced the

progressive blogosphere in Brazil has to do with political changes

associated with

the rise of the political left to the presidency, not only in Brazil

but also

in other South American countries, such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile,

Ecuador,

Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Despite being very different

in their

political styles – some more populists, others more institutionalised;

some

closer to socialism and others to social democracy (Cameron

2009; Castañeda 2006; Lupien

2013) – those countries proved able to forge a regional alliance

and a

common Latin American identity. The Latin American elites reacted to

it, by

presenting leftist governments as putting democracy in jeopardy,

sometimes

picturing them as a part of a broader “Bolivariana” or “Chavista”

conspiracy.

Accordingly, they claimed for themselves the performance of the role

of the political

opposition that political parties were not able to exert (Farah

2010). As the political engagement of Brazilian media became

more and more

explicit, professional journalists felt compelled to take side against

them

and, in order to do this, they joined political activists to form BP.

The third and last prerequisite of BP is technological in nature: The new wave of independent journalism and political activism would not be possible in the absence of a media infrastructure allowing low-cost communication between activists, journalists and their public. The rise of blogs, in the early-2000s, and social media networks such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram provided them with the means to present an alternative to the mainstream media – although, as Bailey and Marques (2012) observe, in many cases, originally independent journalistic blogs were absorbed by the mainstream media. Furthermore, the networking character of these media allowed activists and journalists to forge strategies permitting them to reach a much larger public that would be possible if they acted in an isolated manner.

3. Structure

BP is a complex organisation with

porous

borders. It includes agents with different (although essentially

compatible)

agendas, institutional profiles, and models of action. This section

explores BP

as a particular type of media ecosystem (Magalhães

and

Albuquerque 2017; Rovai 2018),

describes the

characteristics of the actors taking part in it, the types of

relationship they

have established with each other, and the role performed by Barão

de Itararé

as a vanguard agent, which provided BP with a considerable degree of

organicity.

3.1. Typology of BP Members

The members of BP differ in their

nature,

status and social capital type (De

Magalhães

Carvalho 2018). As its origin coincides with the rise of the

personal blogs

(Aldé, Escobar and Chagas 2007; Quadros,

Rosa and Vieira 2005), BP was initially a

confederation of individuals but, since then, it has evolved and

included

other, more institutional types of agents. Individuals form the most

important

aspect of the BP ecosystem. Notable cases include Rodrigo

Vianna’s O

Escrevinhador and Conceição Oliveira’ Maria Frô. In some cases, individual blogs

evolved to

become small journalistic outlets, as Paulo Henrique Amorim’s Conversa

Afiada, which is run by four journalists. There are also more

consolidated

journalistic groups, such as Brasil 247, Opera Mundi,

Revista

Forum, all originally online, and the online version of the

magazine Carta

Capital, and other media related to political parties, such as

the web portal

Vermelho that is associated with the Communist Party of Brazil

(Partido

Comunista do Brasil, hereafter PCdoB), and PT na Câmara that is

associated with

PT (De Magalhães Carvalho 2018;

Magalhães and Albuquerque 2017).

A BP membership is associated with

different

types of sources of authority. The three most relevant types are

journalists, activists

and politicians. Journalists have the more prestigious position in the

BP

ecosystem. Many of them had distinguished careers in the mainstream

media

before joining BP, and some were able to conciliate both activities (Guazina 2013). Conversa Afiada’s

Paulo Henrique

Amorim worked for a long time as the anchor of Globo Network’s

newscast Jornal

Nacional and Jornal da Globo and remained as the anchor

of the

Record Network until 2019, when he was fired. He eventually passed

away a few

weeks thereafter. Viomundo’s Luis Carlos Azenha worked as a

television

reporter on the SBT, Manchete and Globo

networks. Luis Nassif,

from GGN

Jornal, was a member of the Editorial Council of the newspaper Folha

de

S. Paulo. Paulo Nogueira, the editor of Diário do Centro do

Mundo held

editorial and foreign correspondent positions in Veja, Exame

and Época.

Socialista Morena’s Cynara Menezes formerly worked for Folha

de S.

Paulo and the Veja magazine. The founding members of BP

began their

blogs as personal projects, parallel to their professional careers,

according

to the spirit of “personal blogs” of the mid-2000s, and posteriorly

professionalised

them (Guazina 2013). They sustain an

ambiguous

relationship with the mainstream media as, on the one hand, they

contend they

don’t do real journalism, as they are compromised with economic and

political

interests but, on the other hand, their past work in these very media

paradoxically provides them with journalistic authority (Zelizer

1992) which lends credibility to BP as a whole.

Different from journalists, whose

foremost

interest in BP lies on exerting journalism far from the imposed

constrains by

the mainstream media, activists perceive it as a means for promoting a

political

cause. Activists are much more diversified in their authorizing

sources and

styles than journalists. Conceição Oliveira, the head of the blog Maria

Frô

describes herself as a historian and educator who fights for racial

and gender

equality. Created as a strictly personal blog, Maria Frô

subsequently

acquired a more political tone. It later was hosted in the web portal

Forum.

Oliveira also co-operates with other BP media. Another prominent

member of BP

is Eduardo Guimarães, a lawyer who had no previous political

experience before

founding his Blog da Cidadania.

The boundaries between the

identities of

journalists and activists are considerably porous, however, as BP

descends from

the independent journalism movement. The case of Altamiro Borges –

responsible

for Blog do Miro, and one of the most important articulators of Barão

de

Itararé – is a case in point in this respect. He graduated in

journalism studies

in 1979, the same year he became affiliated to PCdoB. Since since then

he has engaged

in the midialivrismo (free media) movement and has been allied

with other

social movements such as the MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores

Rurais Sem

Terra, Movement of Landless Rural Workers). The blending between

the

journalist and activist identities is particularly notable in some of

the more

institutionalised actors of B such as Revista Forum, Carta

Maior

and Brasil de Fato, as their origins are related to the World

Social

Forum, an anti-neoliberal globalisation event whose first edition

occurred in

the city of Porto Alegre in 2001 (De

Magalhães

Carvalho 2018).

The third category, politicians,

refers to

individuals who had a political career before joining BP, political

parties and

other political organisations. Two parties – PCdoB and PT – have been

particularly active in BP. PCdoB was a junior partner during the

PT-led

governments, but in BP their asymmetrical relationship was somewhat

inverted.

PCdoB benefited from its large experience in communication in

accordance with

Leninist principles. When it split from PCB (Partido Comunista

Brasileiro/Brazilian

Communist Party) in 1962, PCdoB inherited the newspaper Causa

Operária (Worker’s

Cause), which was deemed illegal during the military dictatorship

(1964-1985).

In 2002, PCdoB was a pioneer in using digital media as a resource for

party

communication, as it created the web portal Vermelho (Red). Causa

Operária and Vermelho adopted totally different

communicative

logics: While Causa Operária targeted hardcore activists, in a

time when

they faced intense political repression, and used a very politicised

language, Vermelho

looked to reach a broader public through a more informative approach,

which is

expressed by the slogan “the well-informed left” (Mourão

2009).

3.2. BP’s Networking Structure

More than a group of individuals, BP is also

defined by the concrete relations the individuals involved in it

establish with

each other. Working as a pack, BP is a force to be respected. It works

through

a verticalised network structure, which is built through reciprocal

quoting,

sharing of posts, linking to other members’ pages and “official”

policies of

partnership, which are indicated in the blogs’ blogrolls. This allows

the

messages originally posted by particular members to reach a much

larger

audience than it would be possible otherwise. A network schema of the

relations

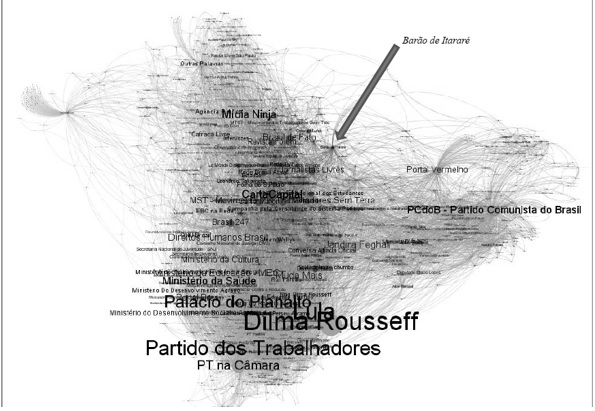

between BP members’ Facebook pages can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1: BP Network in Facebook

This logic results in a hierarchical model of

organisation. The central position in the system is occupied by

prestigious

journalists and activists, in most cases belonging to BP’s first

generation (Magalhães and

Albuquerque 2017). Their

prestige allows their posts to be shared with a wider range of people

than

others. The second level refers to other actors identifying themselves

as

members of BP. Many of them joined BP later and do not use blogs but

have social

media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and other platorms that

they use

to echo BP’s content.

The third level refers to agents that do not belong formally to the BP universe, but establish some tactical alliances with it, motivated by common interests or sensibilities. A particularly relevant case refers to other leftist activist media organisations that differ from BP in their political and organisational approaches. Two particularly relevant cases refer to Mídia Ninja and Intercept Brasil. Mídia Ninja – Ninja is an acronym for Narrativas Independentes, Jornalismo e Ação (Independent Narratives Journalism and Action) – is a collaborative journalism project providing live coverage of protests through the use of cell phones, which gained momentum during the Jornadas de Junho in 201 when activists in their coverage provided live testimonies of police brutality (Cammaerts and Jiménez-Martinez 2014; Penteado and Souza 2016). Initially, BP actors were mostly suspicious both of Mídia Ninja’s unmediated journalistic methods and its political agenda, as they were sceptical or even critical of the Jornadas de Junho’s political intentions and impact. However, BP and Mídia Ninja established closer ties after 2016, when they allied in defence of President Rousseff’s government, which faced a process of impeachment. In the same line, The Intercept Brasil, the Brazilian branch of The Intercept – which played a central role in the Wikileaks case – gained a lot of prestige among BP members in consequence of the Vaza Jato initiative, which presented disturbing evidences about the political motivations behind Lava Jato and pointed to the operation as an effort for toppling President Rousseff and putting former President Lula in jail.

3.3. The Role of Barão de Itararé as BP’s Political Vanguard

Online networking practices have a

great

importance in forging BP as a coherent political media group, but

offline

models of organisation are also essential. Barão de Itararé

has a

crucial role in institutionalising BP. The origins of Barão de

Itararé

can be traced to the Confecom (Conferência Nacional de

Comunicação

or National Conference of Communication), in 2009 (Rovai

2018). At that time, the Brazilian government called

representatives of

diverse civil-society organisations to discuss the model of media

communication

existing in Brazil, and proposing modifications to it (Intervozes

2010). A similar approach was adopted later with respect to the

Marco

Civil da Internet in 2014. Many proposals resulted from the

meeting, as for

instance: the acknowledgement of communication as a social right; the

creation

of a National Communications Council, which would be responsible for

establishing and monitoring public policies on the sector; public

funding

policies for the media and measures intending to avoid property

concentration.

These proposals alarmed the mainstream media organisations, which

accused Confecom

of trying to establish a potentially authoritarian model of control of

communications. Contrary to what was happening with the Marco

Civil, the

measures proposed by Confecom were not approved by the Brazilian

National

Congress. Nevertheless, Confecom was the seed of BP, thanks to the Barão

de

Itararé’s efforts.

The Barão of Itararé Center

was

created in May 2010 with the purpose of “creating something capable of

reuniting social movement activists with journalists and bloggers who

took part

in Confecom” (Borges 2016). In August, it

promoted

the First National BlogProg Meeting in São Paulo. Other meetings

followed in

2011 (Brasília), 2012 (Salvador), 2014 (São Paulo), 2016 (Belo

Horizonte).

Additionally, Barão de Itararé promoted other events, such as

an

international meeting in 2011. In 2013, it sponsored the first edition

of the

National Course of Communications for Media Activists, targeting

activists from

community, unions and alternative media.

According to its president Altamiro Borges, Barão de Itararé has four core objectives: 1) to take part in the fight for the democratisation of the Brazilian media; 2) the support of alternative media in Brazil; 3) the study of the transformations happening in the media landscape at the present; 4) the education of new communication activists. In order to do this, Barão de Itararé conciliates a rigid hierarchical structure, which include a President, a General Secretary, different Directors, a Fiscal Council and an Advisory Council with a considerable diversity in its membership, including intellectuals from different leftist groups. As Penteado and Souza put it, it “presents a transitional model between the traditional one and those exclusively based online, as it sustains a verticalized structure and actors associated to it preserve their autonomy to act and produce content” (2016, 47-48). These characteristics constitute Barão de Itararé’s role of a political vanguard role in BP. Although activists associated with PCdoB have a particularly prominent role in Barão de Itararé, their influence on the BP agenda is quite limited. PCdoB is not a significant player in national politics, and therefore its political ambitions are modest. This allows other agents to feel comfortable with Barão de Itararé’s role. Paulo Henrique Amorim, whose core source of authority is associated with journalism, provides an example:

I am sympathetic to the Instituto de Mídia

Alternativa Barão de Itararé, which tries to gather giant egos around

punctual

missions. But his president Miro Borges often succeeds. The movement’s

results

are stronger than the sum of progressive bloggers. They have a role

that I

think is formidable: to disseminate the poison that, in the end,

contaminates

the dominant system (Amorim 2017).

4. Modus Operandi and Impact

Putting it simple, BP provides the

basis for

a critical counter-public – that is a counterhegemonic public sphere (Fuchs 2010; Negt and

Kluge 1993)

– aiming to challenge the views disseminated by the mainstream media.

As BP is

not only a vehicle, but a media ecosystem (Magalhães

and

Albuquerque 2017; Rovai 2018), the

activities

of its members include not only producing and divulgating media

content, but

also sharing material produced by fellow members, or other critical

content. In

most cases, the material vehiculated by BP consist of pieces critical

to the

mainstream media news coverage, as well as interviews and analytical

pieces,

and more rarely, in-depth reporting.

A concrete example, referring to

the Bolinhagate

incident, illustrates the dynamics of BP collaboration in opposing

mainstream

news media framings. In the morning of October 20, 2010, just a few

days before

the presidential elections – in which PT’s Dilma Rousseff appeared as

a clear

favourite – José Serra, the main candidate opposing PT’s government

was hit by

an object on his head, during a campaign walking tour in Rio de

Janeiro. The

walking tour was then cancelled, and Serra was taken to a hospital.

The scene

was registered by a Folha de S. Paulo reporter with a cell

phone camera,

and at night, it was exhibited by Jornal Nacional, Rede

Globo’s main

newscast, in a two and half minutes news piece that described the

object as

being solid, and therefore the situation as an attempt against Serra,

made by

PT activists. In the following day, Jornal Nacional dedicated

seven

minutes to the incident, presenting a non-official report made by the

forensic

expert Ricardo Molina. Other mainstream news media, such as the

newspapers Folha

de S. Paulo, O Estado de São Paulo and Veja

magazine, echoed

the idea that Serra had been hit by a solid object.

Then, Daniel Florêncio, a film

maker, posted

on Twitter a video entitled “Bolinhagate – the Jornal Nacional

edition”,

which denounced the mainstream media’s coverage as a fabrication.

According to

him, Serra was hit by a paper ball (bolinha de papel in

Portuguese), and

not a solid object (in fact, posterior images did not show any bruises

on

Serra’s head, and this is significant, as he is bald). The video was

retweeted

by Cynara Menezes and other influent bloggers and then went viral. Viomundo

published a letter, written by the Federal Forensic Experts

Association,

raising doubts about the mainstream version of the incident. Other

important BP

vehicles shared the letter. Rodrigo Vianna published on his blog O

Escrevinhador that some journalists from the Globo Network

became so

ashamed of the Jornal Nacional’s seven-minutes news segment

that they

booed when it aired.

Humour was another resource

employed to

spread the message. Serra was portrayed as the Matrix’s character Neo,

dodging

a paper ball. A picture showed a paper ball with the X-Files title “I

want to

believe” behind it. Activists even created a flash game, which invited

players

to throw paper balls at Serra, as he tried to hide behind the Jornal

Nacional’s bench. BP’s version reverberated in the international

media and

hashtags related to the case became trend topics on Twitter.

The Bolinhagate case presents a

vivid example

of how a collective effort made by BP members allowed them to

successfully

counter mainstream media framings. BP members made intensive use of

social

networking sites to propagate their narratives. Comparative analysis

shows that

Brasil 247, one of the most prominent progressive bloggers, managed to

gather

more visibility than some traditional media organisations.

Time-series of the total shares of

publications on Facebook reveals that the Brasil 247 fan page reached

16

million shares on 2016, the year of Dilma Rousseff’s ousting by the

Brazilian

Parliament. In comparison, O

Globo,

one of the largest newspapers in the country, shows an opposite trend

of decay

after 2014. Results shed light on BP’s

struggle for

online visibility, as Progressive bloggers were able to amass more

shares than

resourceful media organizations.

5. The Challenges ahead of BP

Having been created during the

PT-governments era, BP has been facing unprecedented challenges in

recent

years. During the second term of Dilma Rousseff’s presidency, PT

politicians

and its allies became subject to a continuous harassment by the

judiciary,

public prosecutors, the press, and far-right activists. Things became

worse

when vice-president Michel Temer took Rousseff’s place after her

impeachment.

In order to avoid PT’s return to power, former president Lula – who

was the

favourite in all electoral polls to win the presidential race – was

arrested. The

Brazilian Supreme Court prohibited that Lula gave interviews to the

press under

the allegation that this could “disturb” the electoral process.

Additionally,

during the entire campaign the mainstream media presented Fernando

Haddad, who

replaced Lula as PT’s candidate, as being a political extremist who is

just as

dangerous to democracy as Jair Bolsonaro (Feres

Junior

and Gagliardi 2019).

The Brazilian mainstream media has traditionally refused to recognise BP members as legitimate media agents, as they claim for themselves the monopoly of the right of doing genuine journalism. To be sure, their monopolist demands are so extensive that, in October 2016, the Associação Nacional de Jornais (National Newspapers Association or ANJ) required that the Brazilian Supreme Court limits the activities of the Brazilian branches of foreign online journalism outlets – as, for instance, BBC Brasil and El País Brasil – under the allegation that they violate a Constitutional limit that establishes a 30-percent limit of foreign participation in Brazilian media organizations (Folha de S. Paulo 2016). Mainstream media play an even rougher role in the fight against their BP competitors, which they call “dirty blogs” and to whom they deny a journalistic status, despite the fact that in many cases bloggers previously had a solid career in the mainstream media.

The consequences of this can be very serious, as illustrated by the case of Blog da Cidadania’s Eduardo Guimarães. In March 2017, he was detained by the Federal Police under the orders of Judge Moro, who accused his blog of being a “vehicle of political propaganda” and releasing confidential information that put at risk the Lava Jato’s investigations. According to Moro, as Guimarães was not a journalist, he had no right to the legal protection offered to journalists. More recently, in 2019, Glenn Greenwald, the Pulitzer Prize winner ahead of the Intercept Brasil was portrayed by part of the mainstream media as being a hacker, rather than a journalist, in an attempt to demoralize the Vaza Jato series, presenting it in a criminal framing.

A second challenge is the emergence

of a

highly popular alt-right media ecosystem. In the events leading to the

parliamentary coup against Dilma Rousseff, strong machines of

far-right

propaganda disputed the narratives and discourse both from the

traditional

journalism vehicles and from progressive bloggers. The far-right

ecosystem is a

loosely connected network of diverse actors, ranging from journalists

fired

from the national press, authoritarian politicians, neo-Pentecostal

preachers,

digital savvy youngsters, and a myriad of parody/fake accounts (Santos

Junior 2019). The far-right groups’ model

of operation differs from BP particularly considering the

anti-systemic

hostility against parties, as well as the political, journalistic and

intellectual

establishment (Sponholz and

Christofoletti 2019). The communication practices resemble

astroturfing and

informational warfare techniques such as the public harassment of

opposition

leaders, physical threats; all sorts of innuendo and smear campaigns (Santos Junior 2019).

Finally, a more recent development

refers to

the moral panic that has been generated, in a worldwide scale, around

fake news

(Carlson 2018), which gained ground in 2016, after the referendum that

decided

for the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union (Brexit) and the

election

of Donald Trump as the President of the United States. In both cases,

“Russian

meddling” was blamed as one of the key factors explaining these

electoral

results (Boyd-Barrett 2019). The fake

news

problem gained a lot of attention in March 2018, when it was revealed

that

Cambridge Analytica, a political strategy company that worked for

Trump,

irregularly obtained data from more than 50 million Facebook users,

and

Facebook did nothing to prevent this surveillance.

This scandal contributed to

aggravate

already existing accusations against social media platforms as being

co-responsible for the fake news wave. Reacting to these critiques,

social

media platforms engaged in a series of practices that, arguably, aimed

to

contain fake news diffusion. In Brazil, Facebook Journalism Project

and Google

News Initiative provided financial backing for Projeto Comprova

(Comprova

Project), an initiative joining three fact-checking agencies (Lupa,

Truco

and Aos Fatos) and news media outlets – some of them belonging

to the

mainstream media, as Veja, Folha de S. Paulo and O

Estado de

São Paulo (Strano 2018). Added to

this, Facebook

endowed Lupa and Aos Fatos with the responsibility of

checking

the distribution of fake news in its platform (Facebook 2018).

Perpetrators

would be eventually punished with a temporary or even permanent ban.

Although

fake news has been often associated with the far-right alt-media, the

new

censorship dynamics established by Facebook and the fact-checking

agencies

allowed them also to target BP members. For instance, on June 12,

2018, Revista

Forum published the information that Pope Francis sent a chaplet

and a

letter to Lula, in order to express his solidarity to him. Although

there were

controversies with respect to details of the incident, Lupa promptly

classified

this news as fake news and as a consequence Revista Forum was

subject to

retaliatory measures, which included a temporary Facebook ban.

6. Bolsonaro’s Government and the Unexpected Opportunities for BP

At

a first

sight, the rise of Jair Bolsonaro – an unabashed defender of the

previous

Brazilian military regime, who once said he intended to shoot

leftist activists

– to the Brazilian presidency seems to put BP in great peril.

Surprisingly,

this appears to not be the case. Bolsonaro’s far-right activists do

not

identify BP as their prime adversary. Instead, they have focused

their

attention on the mainstream media, which they accuse to be “leftist”

and

“petista”. Although some leftists have been targeted by Bolsonaro

activists’

harassment – The Intercept Brasil, in particular – this

happened in a

much less systematic manner than it would be expected. Indeed, it is

possible

to argue that Bolsonaro’s disastrous and divisive style of

government provides

BP with promising political opportunities.

In

order to

understand that, it is necessary to highlight the very special

circumstances

allowing the 2016 coup against President Rousseff to happen. This

was only

possible because different fractions of the Brazilian political

right joined

forces with the mainstream media, leading sectors of the judiciary

and the

Prosecutor’s Office, the

Federal

Police and military leaders to topple PT by any means (Albuquerque

2019; Tatagiba 2018). By

blaming PT as the source of all corruption existing in Brazil, they

succeeded

in presenting the Brazilian left in a criminal framing and contended

that the

solution for the Brazil’s political problems was to be achieved by

judicial

means. Judge Sergio Moro emerged, in their discourse, as the leader

of a moral

crusade, and the main antagonist of Lula, who was pictured as the

mastermind of

the enormous corruption schema that, allegedly, was led by PT (Damgaard 2018; Feres

Junior and Gagliardi 2019). The far-right activists

associated with

Bolsonaro had a subsidiary role in this arrangement, as they were

responsible

for assembling people for the anti-PT manifestations and physically

intimidating

the leftists (Santos Junior 2019; Tatagiba 2018), who

the press, conveniently, ignored.

Contrary to Rousseff, vice-president

Temer, who

took her place, had several accusations of corruption pending

against him. In

his government, several social policies established by the PT-led

governments

were reverted, the economy stalled, and the confidence in the

institutions of

representative government collapsed (Goldstein 2019). In

2018, Lula emerged as the clear favorite to win the elections, but

he was put

in jail on the orders of Judge Sergio Moro. Contrary to the

mainstream elites’

expectancies, however, this did not benefit the institutional right.

Rather,

the crisis of legitimacy of the representative institutions, which

resulted

from the Lava Jato Operation, opened the way for the antisystem

candidate Jair

Bolsonaro. He disputed the second round of the election with

Fernando Haddad, a

candidate with a political moderate profile, who was the former

mayor of the

city of São Paulo and succeeded Lula as the PT candidate. Although

the

mainstream media were not sympathetic to Bolsonaro, they actually

preferred him

to Haddad, who was presented as being as dangerous to democracy as

Bolsonaro –

but worse than him, because he supposedly was a radical leftist (O Estado de São

Paulo 2018).

The rise of Bolsonaro to the

presidency proved

to be disastrous for the unity of the Brazilian right. Even though

the

mainstream media and rightist forces support Bolsonaro’s neoliberal

reforms,

his outrageous style of government, poor economic indexes and

pathetic

performance in international forums (as in his inaugural discourse

in the UN

General Assembly), blatant nepotism (illustrated by his attempt to

nominate his

son Eduardo Bolsonaro as Brazilian Ambassador to the United States),

and, last

but not least, reports about his family connections with criminal

organisations

(UO

2019) have

raised a severe criticism among the mainstream press – although

nothing

comparable to the treatment they gave to Lula or PT. In his turn, in

many

occasions Bolsonaro complained about the mainstream media coverage

of his

government – for instance, he threatened to stop giving interviews

unless they

“tell the truth” about his discourse at the UN – and even suggested

he could

take measures to economically constrain some media. Bolsonaro also

has

maintained conflictual relations with the Brazilian Congress,

Supreme Court,

and even his own political party. The popularity of the president

plummeted. He

has been rated as the worst first term president so far, and even

some of his

far-right supporters now abrogate him.

The institutional crisis is not

limited to

Bolsonaro’s government, however. When, Sergio Moro accepted his

invitation to

be the Minister of Justice, the credibility of the Lava Jato

Operation suffered

a major blow, as his impartiality became highly questionable.

Although part of

the mainstream media initially presented him as the “rational”,

“institutional”

face of the government, his prestige was damaged by Bolsonaro’s

numerous

scandals and public acts to demote him. Even worse, the Vaza Jato

series – a

major investigative report led by the renowned journalist Glenn

Greenwald on leaked

Telegram chats among task force members – indicated that the process

that led

to Lula’s imprisonment was a judicial farce, as the Judge and the

prosecutors

articulated their actions not only with each other, but also with

the

mainstream media, in an effort to de-moralise Lula and PT. Indeed, Folha

de

S. Paulo’s newspaper present self-criticism regarding its

coverage of Lava

Jato (Lima

2019). At the

present, the Brazilian judiciary is deeply divided at all levels. In

sum,

Brazil currently experiences an extraordinarily serious

institutional crisis in

all branches of government.

As serious as the Brazilian current

situation

may be, from the perspective of the Left and BP in particular, it

represents a

political opportunity. Once formidable, the forces that overthrew

Dilma

Rousseff from the presidency and put Lula in jail are now divided

and have

spent a lot of energy fighting each other. At the same time,

mounting public

evidences indicate that Lula’s image as the mastermind of corruption

in Brazil

was a fabrication with political purposes. This, together with the

dignity shown

by Lula in jail – he refused to make any deal with the Justice

Department – and

the huge contrast between the achievements of his government and the

disasters

that followed the 2016 coup provide a fertile ground for the

re-organisation of

the left in Brazil. At a time when the adversaries are divided, the

ability of

BP to work as a political communication vanguard makes it a very

relevant

instrument to unify the discourse of the left around a common

rhetoric and

cause.

7. BP in Perspective: The Role of Vanguard in Networked Media Activism

In the 2010s, a new orthodoxy

emerged

regarding mediated social activism, having in the works of Castells (2012) and Bennett and Segerberg (2013)

their main exponents. Based on protests

occurring in different parts of the world – Tunisia, Iceland, Spain,

United

States, Iran, among many other examples – they suggested that the

Internet

offered brand new opportunities for political mobilisation, as it

allowed

people to connect to each other beyond the limits of physical space.

According

to Castells, the digital media allow individuals to recognise common

problems

and, then, by joining forces and occupying public spaces, to challenge

the

established powers. As these movements originate in the emotions of

individuals, shared through networked cognitive empathy, they “are the

less

hierarchical in their organization and the more participatory in the

movement”

(Castells 2012, 15).

In a similar vein, Bennett and Segerberg identify these movements as organised on the basis of a digitally networked connective action model, which differs from the traditional collective action model, as it is neither structured in reference to an organising centre nor does it have a hierarchical structure. Rather, such movements are based on the phenomenon of personalised politic that features “citizens seeking more flexible association with causes, ideas, and political organizations” (Bennett and Segerberg 2013, 5). In both cases, the idea that vanguards are an indispensable part of political movements seem to be an anathema.

Yet, as impressive as these movements seemed to be at a first glance, their capacity to produce concrete results in the mid-term proved to be questionable at best, as they were not able to secure sustainable changes and, worse, in many countries governments actually turned to the right or even, as in Brazil, to the far-right. As Gerbaudo (2013a; 2013b) observed, in reference to Egypt, the organisational fragility of the prodemocracy movement, closely associated to the informal character of mobilisation and the model of leaderless resistance, not only prevented them to reach their goals but, indeed, resulted in a military coup that launched the country again into a full dictatorial state. This suggests that, contrary to the hopes of Castells and Bennett/Seberberg, vanguards may still be necessary to convert revolutionary situations into revolutionary outcomes (Tilly 1978).

Contrary to the dominant view, this article argues, with basis on the example of BP, that there is still room for the collective action in networked movements, and old models of organisation, associated to the socialist movements – as the role of the political vanguards – remain relevant in the digital era. As tempting as the ideals of “personalisation” and “participation” may be, they don’t provide a solid basis for coherent collective movements (Fenton and Barassi 2011; Fuchs 2010). However, the concrete manners to instrumentalise political vanguards are not obvious, as the present social and technological circumstances differ sharply from those existing when the notion of political vanguard was coined (Pimlott 2015). For this reason, it can be instructive to analyse concrete initiatives based on the political vanguard principle as, for instance, BP. More than simply an alternative, BP is a critical media initiative (Fuchs 2010), which combines a networked model of action (through hyperlinks and content sharing) with centralised principles of organisation (Barão de Itararé Center is a central piece in this arrangement). BP also preserves some personalised traits – not a surprise given its origins lie in personal blogs – which help to provide it with a considerable capillarity, but, at the same time, it is a considerably institutionalised environment, in which traditional institutions as political parties, social movements and journalism exert a core organising role. Until today, this model of organisation allows BP to work as an effective critical media environment. However, BP’s dependence on social media may be a factor of risk to its survival, as they, allied to the mainstream media and fact-checking agencies, have employed the rhetoric of combating fake news as a tool for curbing political dissidence.