Postface: Karl Marx & Rosa Luxemburg

Christian

Fuchs

Dead

or Alive?

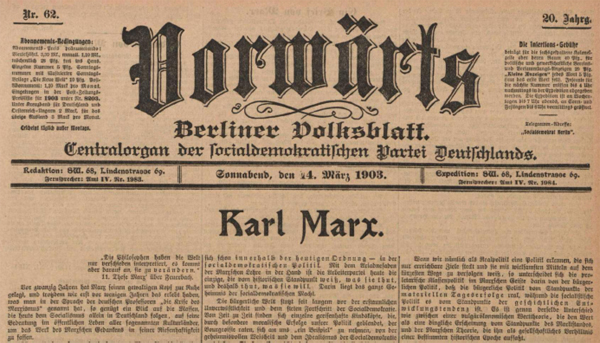

Rosa Luxemburg’s reflections on Karl Marx were published in German on March 14, 1903, in Vorwärts, the newspaper of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. It is a text about Karl Marx’s life and death, the life and death of his ideas and politics, the life and death of socialism, class struggles and alternatives to capitalism. Karl Marx was born on May 5, 1818, and died on May 14, 1883. First published on the occasion of Marx’s 20th year of death, tripleC publishes the translation of Rosa Luxemburg’s tribute to Marx as part of the celebration of his bicentenary. Just like Marx’s critical political economic theory and progressive politics were much needed 20 years after his death, they are also needed and remain alive 200 years after his birth and 135 years after his death. Marx is alive as the ghost that keeps on haunting capitalism as long as the latter continues to exist.

Luxemburg stresses that bourgeois ideologues try to declare Marx’s ideas and politics dead. They did so in 1903. They do so in 2018. Writing in 1903, she says: “In the twenty years since Marx’s death, we have seen a constant series of attempts to destroy Marx’s spirit in the labour movement’s theory and praxis”. 115 years later, the situation is not so different. Much attention is given to Marx on the occasion of his bicentenary. One can discern a bourgeois from a socialist engagement with Marx: bourgeois readings of Marx today argue that he was wrong and his ideas died with him or were already dead while he was alive. What they mean is: “TINA – There is no alternative to capitalism”. Socialist readings acknowledge two facts: (a) Marx’s ideas and politics continue to be of high relevance for understanding and criticising contemporary capitalism. (b) Marx’s thought is dialectical and historical, which means that his basic categories have also evolved with the history of capitalism and the development of Marxian theory. They are not static and fixed, but need to be dialectically developed for today. There is a dialectic of continuity and change of capitalism that manifests itself in the way that Marxian theory uses Marx’s categories to explain capitalism today.

Many

of us are today probably less optimistic than Rosa

Luxemburg in 1903 about socialism’s subjectivity because far-right

ideology has

in recent years been much more strengthened than left-wing worldviews

and politics.

But in objective terms, socialist and Marxian analyses and politics

remain absolutely

vital: Capitalism has since 2008 been in a deep crisis that has

evolved from an

economic into a political and ideological crisis. It cannot be ruled

out that a

new World War will be the result of proliferating new nationalisms.

Capitalism’s crisis and the high levels of inequality, precarious life

and

precarious labour in the world do not just show how much we need

Marx’s ideas

today. The political-economic situation evidences the need of

socialism as an

alternative to capitalism and social struggles for democratic

socialism and

socialist humanism.

Bourgeois

Readings of Marx

When the socialist movement became larger and larger at the time of Rosa Luxemburg, bourgeois thinkers’ criticisms of Marx proliferated. So for example in 1896, Eugen Böhm-Bawerk published Karl Marx and the Close of His System. Böhm-Bawerk came from an aristocratic family (his full family name was Böhm Ritter von Bawerk) and was Minister of Finance of the Austrian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1895 until 1904. At the very start of his essay, Böhm-Bawerk (1949/1896, 3) leaves no doubt that he advances a critique of Marx because the latter had become known to “wide circles of readers”. Böhm-Bawerk for example argues that the “fundamental proposition that labour is the sole basis of value” is “dialectical hocus-pocus” (Ibid., 77) and that Marx’s theory is “a house of cards” (Ibid., 118). Today, also, criticisms of Marx proliferate together with the wider attention that is given to his works. So for example ideological media such as Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, one of the ideological mouthpieces of German capital, claim that Marx was a “false prophet” and that “his central predictions were quite wrong” (FAZ 2017).

How right Marx’s assumption was that a theory of economic value is a theory of time and labour in capitalism, still becomes evident in at least two respects today: a) Capital regularly reacts negatively to demands for the legal reduction in working hours without wage cuts. b) There is a tremendous mismatch between those working overtime on the one hand and those who are unemployed or precariously employed or conduct unremunerated labour on the other hand. Capital tries to maximise the hours worked per year by a single employee and to maximise the average amount of commodities workers produce per unit of time in order to increase profits. “Economy of time, to this all economy ultimately reduces itself” (Marx 1857/58, 173).

The Working

Class

Luxemburg stresses that Marx’s most important insight was that production, class relations, the exploitation of the working class and class struggles form the heart of modern, capitalist society. Given Luxemburg’s stress on the importance of the working class in Marx’s works, politics and thought, reading her text today brings up the questions: Who is part of the working class today? What are the prospects for working class struggles?

The composition and qualities of the working class have changed since the times of Marx and Luxemburg. Class theory today needs to account for phenomena such as precarious freelance labour, knowledge and service labour, the transformation of labour by digital media technologies (digital labour), the vast amount of the unemployed, new forms of unremunerated labour, etc. In addition, working-class consciousness poses a complex problem today whose analysis requires the combination of class analysis and ideology critique. Where is the working class today? Who is part of it? What does its consciousness look like? What are the prospects for the self-emancipation of the working class today? Peter Goodwin (2018) in his contribution to this special issue pinpoints these and other important questions that Marxist theory needs to answer today in respect to the transformation of society’s class structure.

Luxemburg speaks of the “immensity of the work of Marx’s thought”, whereby she points to the fact that Marx was an intellectual worker. He partly worked as a journalist to earn a living, but by and large depended on Engels and other sources of funding for financing his and his family’s life. He had to lead a life in poverty. Today, as the general intellect has become an immediate productive force, intellectual work has become generalised. Higher education and as a consequence highly skilled labour has become much more prevalent. Knowledge work has become an important form of labour accounting for a significant share of value-added. We have experienced the rise of mass intellectuality. Mass intellectuality has under capitalist conditions been accompanied by new forms of precarity and exploitation and does not imply that knowledge workers are automatically conscious of their class status.

Praxis

Luxemburg’s text shows a somewhat exaggerated historical optimism that considers socialist revolution as highly likely. But these passages should not be mistaken for historical determinism and the automatic breakdown of capitalism. In the paragraph where she refers to the passage from Marx’s capital that says that capitalism creates its own negation, Luxemburg uses the conditional form “If the contemporary labour movement […wins]”, which indicates that the “final victory” is all but certain and depends on the unpredictable outcomes of class struggles.

In the context

of the

First World War, she stressed this openness of the historical process in

a

pointed manner by arguing that in situations of severe crisis we face

the

choice between “the

reversion to barbarism” and

socialism (Luxemburg 1915, 388). “This

world war means a reversion to

barbarism. The triumph of imperialism leads to the destruction of

culture […]

Thus we stand today, as Friedrich Engels prophesied more than a

generation ago,

before the awful proposition: either the triumph of imperialism and

the

destruction of all culture, and, as in ancient Rome, depopulation,

desolation,

degeneration, a vast cemetery; or, the victory of socialism, that is,

the

conscious struggle of the international proletariat against

imperialism,

against its methods, against war” (Ibid.,

388-389).

“Socialism will not fall as manna from heaven. It can only be won by a

long

chain of powerful struggles” (Ibid., 388).

Luxemburg

in her essay makes clear that the transition

from capitalism to communism can only become a reality if the content

of Marx’s

theory guides political consciousness. The implication is that if

ideologies

(such as nationalism, racism, xenophobia, anti-socialism, neoliberal

entrepreneurship, etc.) and other developments forestall critical

consciousness

and critical action, then capitalism will continue to exist (unless

society as

such breaks down because of nuclear war or other disasters).

Norman

Geras writers in his book The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg that

Luxemburg’s Marxism is radically

different from “that determinist science of iron economic laws which

is the

usual foundation of fatalism and spontaneism” (Geras 2015, 19).

He argues that passages stressing necessity and chance of social

development can be found next to each other in many of Luxemburg’s

works.

Formulations such as the one about “socialism or barbarism” imply that

“[t]here

is not one direction of development, there are several, and the role

of the

proletariat under the leadership of its party is not simply to

accelerate the

historical process but to decide it. Socialism is not the inevitable

product of

iron economic laws but an ‘objective possibility’ defined by the

socio-economic

conditions of capitalism” (Geras

2015,

28). Geras

points out that for Luxemburg, barbarism signifies capitalism’s

collapse. Every

economic crisis is a partial collapse of capitalism. But barbarism

also entails

fascism, warfare, genocide, nuclear devastation, the ecological

crisis, etc.,

which are all immanent potentials and realities of capitalism. So

capitalism

itself is barbarism. For Luxemburg, the collapse of capitalism and the

creation

of socialism are not identical (Ibid.,

35). Luxemburg’s

interpretation of Marx fuses “objective laws with the

revolutionary energy and will, which, on the basis of that theory,

attempt

actually to change the world” (Ibid.,

37).

It

should be noted that in the passage from Capital Volume 1

that Luxemburg discusses, Marx (1867,

929) speaks of a “natural process” and not, as incorrectly

translated in

the version used in the Marx & Engels Collected-Works, of a “law

of Nature”

(see Fuchs 2016, 69-70, for a discussion of

the

translation of this passage from German to English). The difference is

that in

19th-century science, laws of nature were considered deterministic,

whereas

processes in nature always have a certain level of unpredictability.

The full

passage reads:

“But

capitalist

production begets, with the inexorability of a natural process, its

own negation. This is the negation of the negation. It does not

re-establish

private property, but it does indeed establish individual property

on the basis

of the achievements of the capitalist era: namely co-operation and the

possession in common of the land and the means of production produced

by labour

itself” (Marx 1867, 929).

What

Marx says here is that communism is the negation of the negation of

capitalism

and entails co-operative work based on the common ownership of land

and the

means of production. Capitalism negates itself in its own development

through

crises. Communism is capitalism’s negation of the negation. The

preceding

paragraph ends with Marx’s famous call and demand that the

“expropriators are

expropriated” (Ibid.). This formulation

implies

that the process Marx talks about only

takes place if there are

active subjects who in the course of a revolution take the means of

production

into common ownership. The question of the revolutionary negation of

the

negation is for Marx not one of automatic breakdown,

but of class struggle

and revolution (see Fuchs 2016,

322-324 for a detailed

discussion of this passage).

Materialism

Luxemburg stresses Marx’s materialist concept of

society. But what does it mean that the production of material life

conditions

society, including individual and collective consciousness? Matter in

society

is neither simply the economy nor tangible things we can touch. By

matter in

society, Marx refers to

the process of social production.

That consciousness is grounded in material life

means that the human individual,

its thoughts and language, are not isolated and cannot exist in

isolation, but

only in and through social relations with other humans that are

relations of

production, in which they co-produce the economy, political and

cultural life: “The

ideas which these individuals form are ideas either about their relation

to

nature or about their mutual relations or about their own nature. It is

evident

that in all these cases their ideas are the conscious expression – real

or

illusory – of their real relations and activities, of their production,

of

their intercourse, of their social and political conduct. […] Men are

the

producers of their conceptions, ideas, etc., and precisely men

conditioned by

the mode of production of their material life, by their material

intercourse

and its further development in the social and political structure” (Marx

and Engels 1845/46, 36). The implication is

that ideas, communication, politics, culture, art, science, philosophy,

etc. do

not form a superstructure detached from an economic base, but are

themselves

realms of economic production that have at the same time non-economic

qualities. Whereas the base/superstructure

metaphor is misleading, it is preferable to talk about the material

character

of society as a dialectic of the economic and the non-economic.

Left Socialism’s

Revolutionary Realpolitik

Luxemburg interprets the politics that Marx stands for as revolutionary Realpolitik. She opposes revolutionary Realpolitik to “revolutionary-socialist utopianism” and “bourgeois Realpolitik”. At the time of Luxemburg, the bourgeois Realpolitik of the Left took on the form of revisionist social democracy that stood under the influence of Eduard Bernstein’s doctrine of reformism and society’s mechanical evolutionary development into socialism. Left utopianism took on the form of the anarchist propaganda of the deed.

Isn’t the situation of the Left today quite similarly facing the two dead ends of utopianism and bourgeois Realpolitik? On the one end, we find bourgeoisified social democrats, who advance a purely reformist parliamentary politics that has succumbed to neoliberal ideology. The meaning of social democracy today is as a result completely opposed to the meaning it had at the time of Luxemburg as well as at the time of Marx. On the other end, we find radical social movements, who believe in the power of horizontalism and prefigurative politics. They limit politics to civil society and in an anarchist manner want to change society without taking power. Such movements overlook that the state is itself an important terrain of struggle, that it is a mistake to leave this battleground to bourgeois parties, and that changing society simply cannot start from the outside of society, but requires power and resources that come from the inside of the system and are in a dialectical process of revolutionary sublation turned from the inside out. So whereas contemporary social movement politics is by and large a version of abstract, idealist anarchist romanticism, social democracy has completely adapted to the system. Rosa Luxemburg reminds us that Marx argued for the politics of revolutionary reformism that is based on a dialectic of reform and revolution. Parliament and governments are terrains of struggles that should be strategically appropriated for improving the conditions of struggles. The Left needs both a civil society wing and a party that interact dialectically.

If the Left does not want to leave politics to the forces that dominate today – nationalists, the far-right and neoliberals –, then it needs to reinvent a left socialism that in a similar vein to the political understanding of Marx and Luxemburg is based on dialectics of party/movements, organisation/spontaneity, leadership/masses, reform/revolution. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2017, 278) argue in this context: “The taking of power, by electoral or other means, must serve to open space for autonomous and prefigurative practices on an ever-larger scale and nourish the slow transformation of institutions, which must continue over the long term. Similarly practices of exodus must find ways to complement and further projects of both antagonistic reform and taking power”.

Against

Positivism

Rosa Luxemburg in her reflections on Karl Marx also advances a critique of positivist science and positivist social theory. Positivist research is eclectic, fragmented, theoryless, and follows trendy fashions: “Autonomous flights of thought, a daring glance into the distance or an invigorating deduction are nowhere to be found”. Positivism cannot explain society’s big problems and questions, the large connections of moments within society. It lacks a focus on society as dialectical totality. The academic war that neoliberal academia and postmodernism have for decades waged against Marxist theory has in contemporary society resulted in an academic landscape that is quite similar to the one that Luxemburg criticises.

There is much talk about interdisciplinarity, but in reality interdisciplinarity lacks critical theory and philosophy and is little more than a fancy catchword that aims at turning the university into a business school and corporation and research via the focus on STE(A)M into corporations’ and capitalism’s vassal. In the social sciences and humanities, postmodernism has resulted in a focus on small-scale micro-studies (typically studies of micro-phenomenon A in country or city B), a neglect of understanding society as totality, and a neglect of the development of grand social theories. While academia gets ever more uncritical, society’s global problems get worse. The rise of computational social science and big data analytics is a typical example of how the focus on positivism (in this case via large-scale data analysis) and the lack of grand theories threaten and destroy the critical potentials of the social sciences and humanities (Fuchs 2017). Marxian theory poses a counter-model. It is a true form of inter- and transdisciplinarity that allows situating specific phenomena in their broadest academic and societal context and aims at producing knowledge that helps advancing human emancipation.

200 years after Marx’s birth, his approach is urgently needed in research, theory, politics and society at large. That ‘Marx is needed’ means nothing more than that the critique of capitalism and class is an urgent theoretical and political task. Only Marxian theory and praxis can advance knowledge and a form of politics that help us to overcome the severe problems posed by nationalism, inequalities, ecological devastation, authoritarianism, wars, genocides, and economic and political crises. We need to repeat Marx today.

References

Böhm-Bawerk,

Eugen.

1949/1896. Karl Marx and the Close

of His System. New York: Kelley.

FAZ.

2017.

Der falsche Prophet. FAZ Online, July

8, 2017.

Fuchs,

Christian.

2017. From Digital Positivism and Administrative Big Data Analytics

towards Critical Digital and Social Media Research! European

Journal of Communication 32

(1): 37-49.

Geras,

Norman.

2015. The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg.

London: Verso.

Hardt,

Michael

and Antonio Negri. 2017. Assembly.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.